As an international educator and advocate for immigrant and refugee rights, I often use Costa Rica as an example for humanitarian refugee policies in accordance with international human rights and refugee agreements. In Costa Rica, there are no walls, refugee camps, detention centers, ankle bracelets, border closures, or mass deportations. Asylum seekers are allowed entry and provided legal protection in transit or while awaiting review of their asylum claims. Without camps or detention centers, asylum seekers live in communities that facilitate socioeconomic integration. While the immigration system is strained and processes for asylum seekers are lengthy, they are an example of a humane and dignified way to protect displaced populations.

Migrant populations and the debate over migrants are not new to Costa Rica. However, the term refugee entered the forefront of the Costa Rican national narrative in 2018, when hundreds of thousands of Nicaraguans fled to Costa Rica to escape death, torture, and imprisonment under the repressive Ortega-Murillo dictatorship. Not all Costa Ricans understand or accept Nicaraguan refugees; they often struggle to integrate into education and health systems and to find formal employment, and many face both systemic and overt discrimination. However—in accordance with the guidelines of the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) and the International Organization for Migrants (OIM)—Nicaraguan asylum seekers are given legal protection in Costa Rica upon entry and while awaiting review of their applications for permanent refugee status.

This year, U.S. immigration policy decisions have resulted in dramatic additions to Costa Rica’s migrant crisis. In July of 2022, the Biden administration extended Temporary Protection Status (TPS) for Venezuelan asylum seekers. However, in October, the administration suddenly reverted the TPS for Venezuelans, enacted the Trump administration’s Title 42 policy, and closed the US-Mexico border to all Venezuelan asylum seekers. This quick change in policy left thousands of Venezuelan immigrants and asylum seekers in transit and stranded throughout Mexico and Central America. After fleeing their homes in Venezuela due to increased repression, violence, and a devastated economy caused by the pandemic and Nicolás Maduro’s authoritarian regime; selling all of their belongings to pay traffickers and cover the cost of the journey; and facing the dangerous journey through the Darien Gap in Panama, Venezuelan people were left in limbo throughout Central America and without support, money, food, or shelter.

Venezuelan migrant families are now visible on every street corner in San José, holding handmade signs and Venezuelan flags, selling candies and asking for economic support for their families to stay in Costa Rica with the hopes of eventually continuing their journey north. With no formal shelter or support system in place, informal camps provide temporary shelter for desperate families with no way to move forward and, for many, the impossibility of returning home.

The visibility of Venezuelan families on the streets of San José is uncomfortable for many Costa Ricans. There is a lack of understanding of the situation in Venezuela and the journey that many families are forced to undertake. Some Costa Ricans have responded with handouts of a few coins, food, or clothing. Others, in fear, quickly roll up their car windows to avoid uncomfortable encounters with Venezuelans simply asking for help. Some feel pity for the families, saying phrases like “pobrecitos, los chiquillos” (“Oh, the poor children”). One Uber driver I spoke with was so angered by the number of Venezuelans not working and, according to him, only begging on the streets; he suggested that all families should be sent to harvest coffee and support the economy. Despite this reaction from some Costa Ricans, the Venezuelan families were and are protected under national and international law while seeking asylum in or in transit through the national territory.

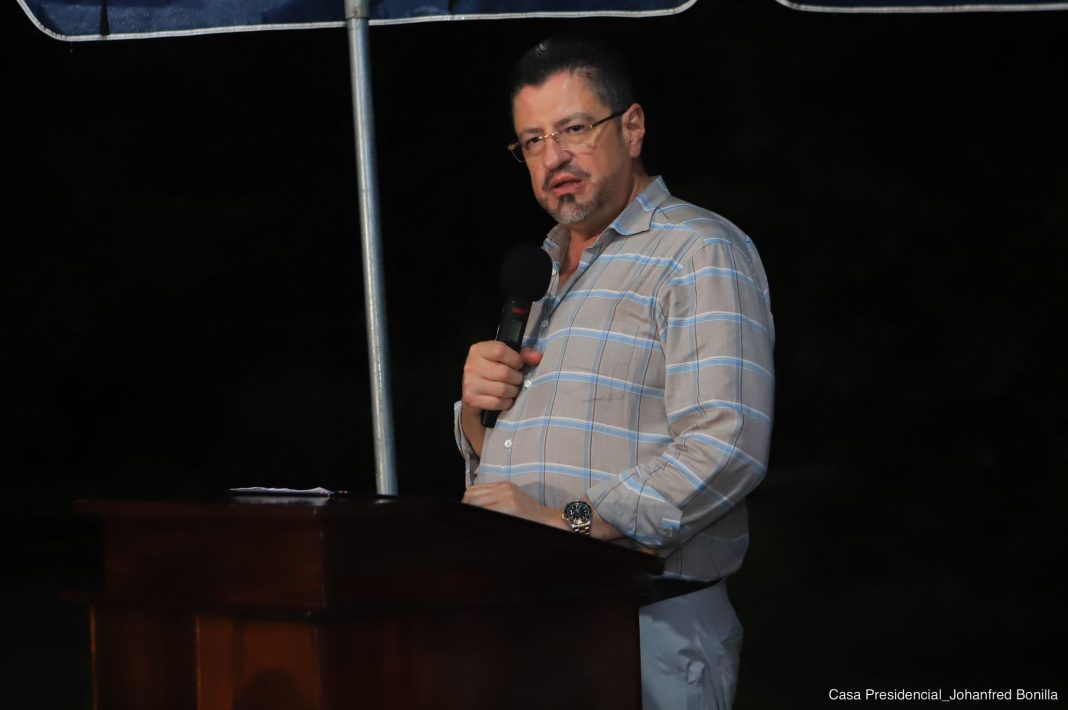

The initial response to the situation by recently elected President Rodrigo Chaves was to offer land transport north to Venezuelan families. According to Chaves, this would prevent beggars and delinquents on the streets of San José and reduce the economic strain on social services. When the option to move further north became difficult, Chaves also offered transport to the southern border with Panama for repatriation flights to Venezuela. Chaves’ narrative became clear; he did not want a visible population of Venezuelans in Costa Rica, especially on the streets of the capital.

Chaves’ populist narrative took a dangerous turn last week. The president declared that Costa Rica would close its borders to all economic migrants entering the country and allow entry only to “political refugees.” He said it was time to act and that immigrants could no longer abuse Costa Rica’s asylum-seeking policy. He also stated, inaccurately, that asylum seekers only must make a phone call to get permission to work—thus fueling the popular narrative that migrants take jobs from Costa Ricans. Chaves criticized the international community for not economically supporting Costa Rica and abandoning economic responsibility for the immigration crisis.

The president’s declarations and threats are inaccurate, misleading and dangerous. The term “political refugee” does not exist. There are only refugees: people who must flee their country of origin to escape any form of persecution, whether it be political, religious, ethnic, or gender-based. Some refugees flee to escape gang violence, and others to escape war or the detrimental effects of climate change. In stating that the country would only accept “political refugees,” President Chaves over-simplified the complex situation of displaced people around the world and put in jeopardy the possibility for people from any country, including Nicaragua, Haiti, Cuba, and Venezuela, to find safety and seek asylum in Costa Rica.

It is not the dream of people escaping dangerous, desperate, and uncertain conditions to live and work in Costa Rica. It is not an easy decision to leave one’s home, family, and community, and make a dangerous journey. Work permits are not, as President Chaves stated, given after just a simple phone call. First of all, that call is costly: the call for an appointment with immigration services costs $3.00 for four minutes and can vary in cost depending upon the volume of calls and wait time. Secondly, the appointment, once scheduled, provides only temporary permission to remain in the country until the appointment date. If, after the appointment, the request for asylum is approved, asylum seekers may obtain permits to work in Costa Rica. However, misinformation and discrimination often prohibit asylum seekers from finding employers that accept the asylum-seeker identification card as a legal document and work permit.

Chaves’ discourse removed the dignity and experiences of all immigrants, asylum seekers, and refugees. This is not the first “wave” of Venezuelans or immigrants to enter the country. Costa Rica is a diverse society composed of Venezuelans, Nicaraguans, Columbians, Cubans, and others, all living in and contributing to the culture, knowledge, and economy of the country. Chaves’ comments ignore the situations that asylum seekers face, and validate xenophobic attitudes towards all immigrants and refugees in the country.

The president’s threats to change immigration and refugee policy send a clear anti-migrant message and threaten the safety of immigrants and refugees in the country. Words matter and words have power. Chaves’ dangerous narrative fuels discrimination, xenophobia, and hate, and places vulnerable people in even greater danger.

It is urgent that we reject the anti-immigrant narrative. Costa Rica must continue to be an international example for humane and just refugee policy. Costa Ricans are now at a critical moment of inflection: the country can choose an inclusive national narrative that provides protection for asylum seekers, or it can head down a new path.

Costa Rica faces an opportunity to double down on its international reputation for human rights, democracy, and peace—or make hostility towards immigrant populations an integrated reality in Costa Rican policies and daily life. We must say no to a dangerous narrative of hate, and we must say yes to a constructive narrative of integration and acceptance.