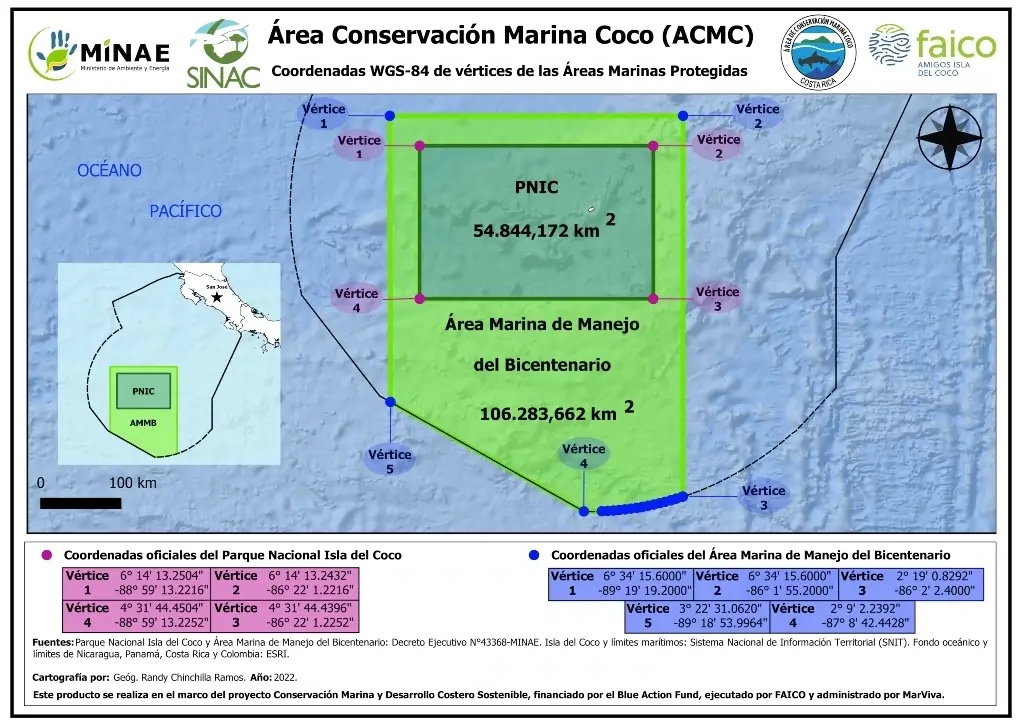

“I have to recognize this: managing a marine protected area that allows for fishing use is also something new for the park system itself,” says Diego Torres, coordinator of the Sustainable Tourism Program at Costa Rica’s Cocos Island National Park (PNIC). He’s referring to the challenge for his organization that comes with managing the 106,285 square kilometers of marine area protected since 2021 by the Bicentennial Marine Management Area, or AMM Bicentenario. This area includes the 46-plus square kilometers that now make up PNIC.

But the challenge that Diego describes for the National System of Conservation Areas, or SINAC, goes far beyond monitoring and protecting all the biodiversity that lives and migrates through an area twice the land size of Costa Rica. For him, the greater challenge is that protection must now go hand-in-hand with the sustainable use of the resources it contains.

In other words, commercial activities such as fishing are now allowed—as long as this doesn’t affect the conservation of the area.

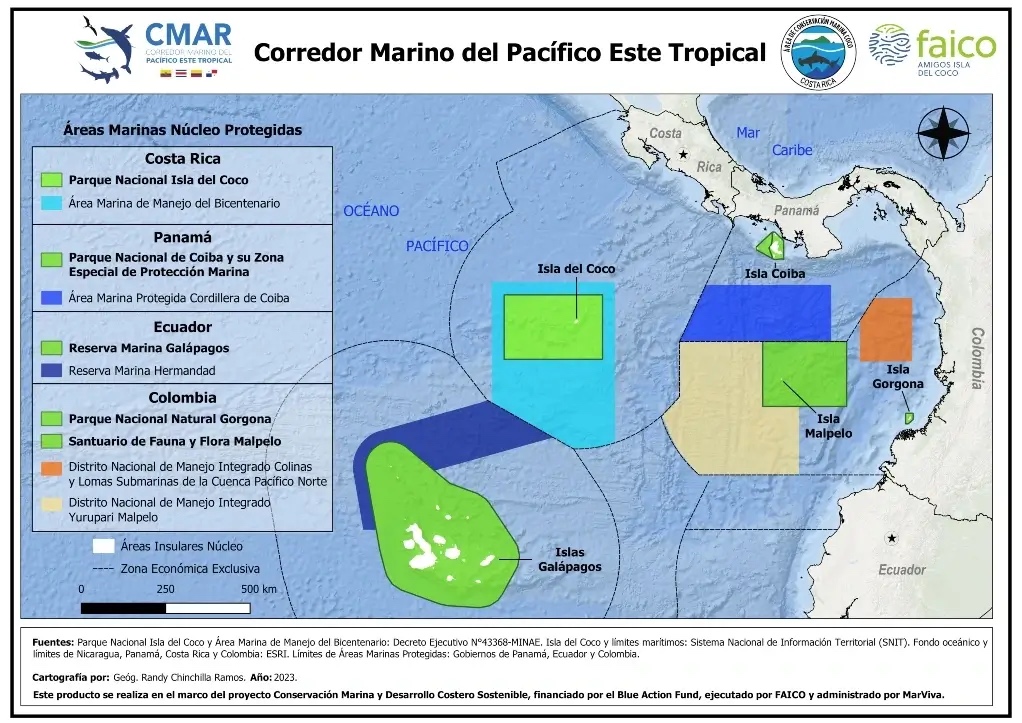

This is the philosophy not only of this Costa Rican protected area, but also of the protected and managed areas that since 2002 have united Costa Rica, Panama, Colombia, and Ecuador in the Eastern Tropical Pacific Marine Corridor, or CMAR. According to its website, it is a regional conservation and sustainable use initiative that seeks proper management of biodiversity and marine and coastal resources through an ecosystem approach, and through the establishment of joint regional governmental strategies.”

That’s why the use of marine resources now goes beyond ecotourism, environmental education, and research. It also involves understanding where resources can be used—especially fishery resources—and defining how this use should be managed. Establishing these guidelines is no simple matter, because commercial and conservation sectors often understand “use” in different ways.

“Because CMAR is an initiative of Environment Ministries, there isn’t a very fluid relationship with the fishing sector in general,” says José Julio Casas, who until July 2025 served as acting technical secretary of CMAR. He assumed that position through his work at the Directorate of Coasts and Seas of Panama’s Ministry of Environment. “That relationship hasn’t been bad, but it’s been distant.”

However, despite the complexity of uniting two opposing poles—uncontrolled extraction on the one hand, and absolute conservation of marine resources on the other—José says there’s a practice that could bring significant benefits to all sectors directly involved in and affected by CMAR.

That practice is sportfishing.

“I see the sportfishing subsector as a key piece that connects various actions within CMAR, because it definitely involves fishing, but it also involves tourism and is related to processes of protection, conservation, and sustainable use,” says José. “At least from my perspective, it’s that cornerstone where the different subsectors that CMAR works with can converge.”

Fishing and the Marine Corridor

The Institute of Economic Research (IICE) at the University of Costa Rica (UCR) concluded that in 2008, the practice of tourist fishing contributed 2.13% of GDP—0.25% more than commercial fishing. In 2019, a study by the Costa Rican Fishing Federation (FECOP) reported that the income of families connected to this activity is, on average, 2.4 times higher than the base salary of a skilled worker.

I’ve been close to the world of sportfishing for more than 10 years. My husband, passionate about fly fishing, turned his passion into our family’s main source of income. FECOP is a client of El Colectivo 506’s consulting services, giving me the chance to learn about other sides of the sector. That’s why I wasn’t surprised when I read studies about the economic and social impact of sportfishing in Costa Rica.

These studies address the practice of sportfishing and its impact throughout Costa Rica. However, after speaking with people at five different institutions—AMM Bicentenario, CMAR, FECOP, MarViva, and the Hubbs-SeaWorld Research Institute—it’s clear to me that the role of this kind of fishing, along with commercial fishing, within CMAR is still undefined.

Diego, from AMM Bicentenario, says that after many setbacks, a process that began in 2023 will soon conclude with the official publication of the General Management Plan for the protected area—“the master management tool for the protected area.” However, there’s still important work to do.

“The next step for the Bicentennial is to develop an instrument called the Fisheries Management Plan, which will determine the operational side of fishing activity,” says Diego. He explains that this management plan “involves defining the types of fishing gear that will be allowed, the species permitted for capture within the Bicentennial, the species that will be prohibited, and also defining the permits the administration must issue for users to enter and fish within the Bicentennial Marine Management Area. When I say users, I’m referring to both semi-industrial fishing—longline fishing in this case—as well as tourist sportfishing.”

This work of creating fisheries management procedures is crucial for all of CMAR, which seeks to be declared a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve.

“That designation isn’t a conservation label at all—quite the opposite. It’s a figure of use: responsible, sustainable use,” explains José, the former CMAR secretary, about what the declaration would mean. “If CMAR wants to establish those national and later transboundary reserves, it has to sit down and talk with the fishing sector as a whole.”

That conversation, José explains, is an important one. CMAR will have to demonstrate to UNESCO that within the corridor, it achieves the objective of “reconciling the conservation of biodiversity with sustainable use.” This reconciliation is a key element in qualifying as a Biosphere Reserve, according to UNESCO’s website.

That conversation, José explains, is an important one. CMAR will have to demonstrate to UNESCO that within the corridor, it achieves the objective of “reconciling the conservation of biodiversity with sustainable use.” This reconciliation is a key element in qualifying as a Biosphere Reserve, according to UNESCO’s website.

“I don’t think it would look very good for a country to take a proposal [to UNESCO] without including the most important use sector within the area they’re working on, which is the fishing sector,” adds José.

Damián Martínez, director of policy and conservation at FECOP, also stresses the importance of including the fishing sector—both sport and commercial—in CMAR’s discussions and research.

“The plan talks about fishing in general [in CMAR’s 2019 Action Plan] as if it were the main threat,” says Damián. He adds that while he understands its impact, in his view the sector hasn’t been sufficiently included in these processes. “So what’s the main problem? From my perspective, it’s that CMAR isn’t incorporating fishing itself as one of its main pillars.”

So how can this path toward sustainable use of CMAR’s resources begin to take shape? The answer might lie in citizen science.

What can sportfishing contribute to conservation?

I’ve seen my husband and his clients collaborate by providing scientists with samples for DNA studies of certain sportfishing stars, such as tarpon. That made me wonder what potential this kind of effort might have within CMAR. In researching the contributions of this sport to science, I found that in 2021, an article in Fisheries Oceanography concluded that given the lack of specific data on billfish populations in Guatemala, Costa Rica, and Panama, “recreational fishing records provide an alternative way to monitor the presence of target species.”

The study was led by Danielle Bates, oceanographer, marine ecologist, and scientific director at the Hubbs-SeaWorld Research Institute. It’s just one of the research projects in which Danielle has relied on the sportfishing community to study billfish such as marlin and sailfish—other stars of sportfishing. Like other key research or umbrella species, such as turtles and sharks, they are highly migratory and sit high in the food chain.

“I started working on a project in 2018 through Stanford University. The goal was to deploy satellite tags on blue marlin and sailfish, focusing on those two species to understand how ocean changes might be affecting their fate,” Daniella explains. “The project arose from the sportfishing industry because 2018 was a very bad fishing year, especially for marlin.” She was referring to another study being conducted between the university and the institute, whose results have not yet been published.

However, for Danielle and the research team she represents, the most important thing about these experiences is the collaboration between the sportfishing community and the scientific community. To carry out their studies—which now also include “a survey of anglers, captains, and officers who’ve been fishing in Costa Rica for more than 10 years”—Danielle’s team has been able to take advantage of boat trips donated by owners and captains. They’ve also had in-depth conversations where they can compare knowledge and experiences.

“I’d say all [the sport fishers] were very interested in the science and in how we use that information to better manage the fishery,” she said. “I think they recognized that many decisions in that part of the world are sometimes made based on incomplete information. So they were very curious to learn more.”

Danielle hopes to expand her research to other species important to the fishing industry, such as tuna and mahi-mahi, and believes these studies can complement the work that many organizations such as MigraMar are doing with species like turtles and sharks. Together, this could generate comprehensive information to manage marine resources sustainably.

“There are certain species that represent particular values—whether for recreational fishing, commercial fishing, the healthy functioning of ecosystems and a biodiverse ocean, or even ecotourism,” explains Danielle. “I’m interested in where all these things overlap, and where they might be separating in space and time, to better understand how we can improve the design of protected areas and fishing zones.

“We need seafood; there are communities that depend on commercial fishing. Humans live on this planet and eat seafood. So how can we imagine managing an area where things can coexist, but where we can also better separate them?”

For Andrés Beita, science coordinator at the nonprofit MarViva Costa Rica, “the sportfishing species [marlin, sailfish, tuna] are priorities for CMAR. Having information about them is very useful.” Andrés says that’s why he also believes that the information the sportfishing sector can provide—through its own records and reports from the open sea—“can be quite useful, especially when there are limited resources to obtain data, but it can’t replace monitoring.”

Diego, from AMM Bicentenario, agrees.

“Generating information—that is, having the sector itself help us generate that information—is key, because at the end of the day, it’s the users who are out on the water within the Bicentennial. That’s a capacity that maybe we don’t necessarily have right now,” he says.

So, monitoring and studying billfish species appears to be one way that sport and tourist fishing contribute to conservation actions near and within CMAR. But what else can it offer?

Damián, from FECOP, sees two additional opportunities in this relationship: philanthropy, and economic development for the coastal communities of the four countries that make up CMAR, through recognition of the ecosystem services the corridor provides.

“There are wealthy people interested in working with the species of interest, and there’s a real desire to manage fisheries well,” says Damián. He explains that viewing sportfishing as a partnership can attract funding to equip and strengthen the government agencies now in charge of CMAR’s sustainable management.

In terms of strengthening the concept of ecosystem services, Damián says that the key lies in including and empowering different stakeholders—not just sport fishers, but all those engaged in tourism within and around CMAR. That way, they can have tools that allow them not only to contribute information, but also to optimize their operations for the benefit of biodiversity and local economies.

“We’re leaving out the main users of these areas,” says Damián. “By addressing tourism and fishing strategically, we could work with those users—and ultimately, what we want are changes in attitudes, such as less pollution and more responsible tours.”

The key is teamwork

“Cooperation isn’t an option. It’s a necessity,” said Jair Urriola Quiróz, current executive secretary of CMAR, during a virtual training session for journalists on July 10, 2025. He was referring to how collaboration among government leaders, nongovernmental organizations, and funders has paved the way for the construction and consolidation of CMAR—an important lesson from this major international project.

After talking with so many stakeholders and participating in the training The Ocean on the Front Page, it’s clear to me that this cooperation includes actors such as sportfishing.

“We believe that well-managed sportfishing can be a very good alternative for CMAR—regulated, with good practices, and with an equitable distribution of benefits,” says Andrés, from MarViva.

“I’ve worked with fishers my whole career, both recreational and commercial,” says Danielle. “I love working with them because I think most fishers are, in a way, natural scientists. You go out with them, and they’re analyzing the water. They’re looking for birds. They have in mind what the ideal water temperature is. They’re asking: Is the water too brown or too green? Is it too choppy, or is the lunar phase not ideal? I love hearing fishers talk about their hypotheses—because they are hypotheses, right? They have a mental model of what predicts a good or bad day of fishing.

“I think fishers have a lot of information that can add value to our understanding of the ecosystem, simply because they’re on the water every day, gathering information—gathering data mentally.”

——

This story was published thanks to the support of the initiative Challenges and Opportunities for Conservation in the Eastern Tropical Pacific Marine Corridor (CMAR) by LatinClima, MarViva, and the Tropical Science Center, with support from the Earth Journalism Network and in collaboration with CMAR.