Communities in San Carlos, Amaya, and Perereta transformed their relationship with Bolivia’s most endangered endemic parrot after two decades of working with Asociación Armonía, although the sustainability of the model depends on aging leaders without a clear replacement.

Fabricio Lobaton tells the story in this report, made possible by a grant from the Latin America Solutions Journalism Fund, an initiative of El Colectivo 506, with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network. It was published by Casa de Nadie Casa de Nadie on Nov. 29, 2025, and has been adapted and translated for co-publication by El Colectivo 506. ChatGPT was used to create the first draft of the translation.

Read Part I of his two-part series here.

Counting what matters

Three weeks of hiking along cliffs and canyons in 2021. Teams from Asociación Armonía and Fundación Natura Bolivia covering Santa Cruz, Cochabamba, Chuquisaca, and Potosí. Binoculars. Notebooks. Patience. The national census recorded 1,160 macaws: those associated with rocky outcrops, palm trees, roosting sites, and feeding areas.

Of the individuals recorded, 482 were spotted in the Mizque basin, 398 in the Grande basin, 181 in the Caine basin, and 99 in the Pilcomayo basin. Compared to the 807 recorded in 2012, this represents a 43.7% increase. This is the first time in decades that the numbers have risen instead of fallen.

Guido Saldaña, a biologist who coordinates the Red-fronted Macaw Program at the Armonía Association, explains the importance.

“That number is still quite small for a population, for a species that is unique in the world,” he says. “And also, considering that the macaw is often very exposed to people, because it likes to live in valley areas where there is a lot of agriculture.”

The census also documented reproductive activity. The red-fronted macaw nests in small colonies between September and March. It lays one to three eggs. Incubation lasts 24 to 28 days; the rearing period is 70 to 78 days. Each nest has an average of two chicks, with an estimated survival rate of 48%.

But there are reproductive limitations. Not all pairs nest every year. Guido explains: “Often it depends on the food available, so their bodies can be prepared to reproduce.” Sometimes they wait two or three years between nesting. And the chicks that leave the nest take at least three years to reach sexual maturity.

“Sometimes it’s only in their fourth year that they reach a stage of maturity that allows them to reproduce,” he says.

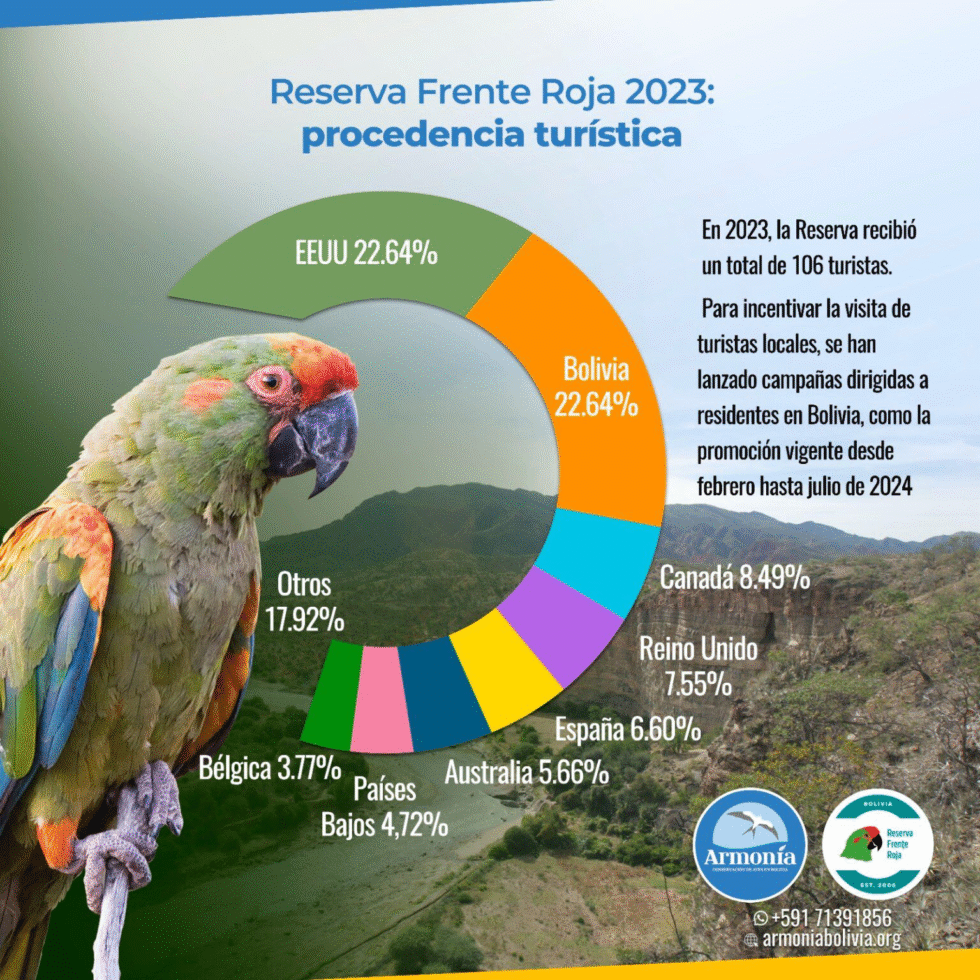

For more than a decade, between 2008 and 2019, the reserve received between 25 and 30 groups of visitors annually. These were small groups, ranging from two to 14 people. The COVID-19 pandemic brought everything to a standstill in 2020 and 2021. For communities that already depended partially on that income, it was devastating.

But 2023 marked a historic record: 187 visitors generated 169,450 bolivianos, approximately $24,500 in direct revenue, according to official data from Armonía shared with Bolivian media. In August 2025, despite political blockades that paralyzed national tourism, the reserve received six groups.

“Of course, after so many years, people themselves have become aware,” reflects park guard Simón Pedrazas. “Since visitors leave a little money, they’ve seen the money and now they see how important it is to conserve the Red-fronted Macaw. And they welcome them very happily.”

But the most profound impact is qualitative.

“Before, people sometimes even captured them for profit,” says Marlene Rivas, cook at the tourist lodge in the Red-fronted Macaw Community Nature Reserve. “Now it’s prohibited. We ourselves are much more careful now.”

Guido confirms this: “Today, they are the main protectors of the red-fronted macaw. When the population declines, they worry and ask me: ‘What do we do? What are we going to show the tourists?’”

The change is also evident in those who grew up with the project. Armin Vargas, a recent park ranger, grew up witnessing the transformation: “Since 2006, we’ve been involved in this work, and as people from this area, we’ve grown up with this desire to preserve it. We didn’t see it that way before. The Armonía organization has come in and opened our eyes.”

Marlene has been working in the reserve for almost 20 years. Armonía continues to promote and expand its projects in the community, considering developing archaeological sites for tourism and beekeeping projects to sell organic honey, always working hand-in-hand with local residents and for their benefit.

Building from the ground up

The effective conservation of endemic species requires immense patience. Twenty years from the start of the project to a 43.7% increase in population.

“Getting there is what was so difficult,” admits Guido. “You can imagine how far we’ve come after 20 years; it’s no small feat, but I think we never gave up and we’ve continued working alongside them.”

Conservation alone is not enough. Real economic alternatives must be offered. Guido is frank about how it worked: “I think the level of poverty, the need, also makes them think a bit about looking for other alternatives.” The drought, the lack of water, the decline of agriculture—all of these factors had made the communities receptive again. Armonía understood this moment.

However, conservation didn’t arrive unaccompanied. Armonía also brought honey production projects to diversify income and helped the communities experiment with alternative crops that reduced their dependence on corn. All of this built trust before the first tourist even arrived.

The lodge reflects the decisions of the local communities. Built with their participation, it accommodates up to 14 people in seven rooms with four hot-water bathrooms. Feeders in the courtyard allow visitors to observe macaws while they eat breakfast. It’s simple and functional; specialized birdwatchers appreciate this authenticity.

The reserve was established by leveraging the communal land ownership system recognized by the 1996 INRA (National Institute of Agrarian Reform) Law, which allows peasant communities to obtain collective titles to their territories. Bolivia has titled 24.8 million hectares under various forms of collective ownership—approximately 24% of the national territory. The communities of San Carlos, Amaya, and Perereta allocated 50 hectares of their titled communal land to create the reserve in 2006, ensuring collective control over land-use decisions.

Community land titling provides greater security, as the community organization and its authorities are responsible for safeguarding rights. This legal framework allowed the Local Management Committee to maintain autonomy over the project’s development, from the design of the lodge to the income distribution structure. Strategic decisions are made by the communities themselves in assembly, with Armonía providing technical support within this local governance framework.

The project’s sustainability didn’t depend on individual leaders. It depended on creating functional community institutions. The Local Administration Committee was structured with elected representatives from the three communities: San Carlos, Amaya, and Perereta. Important decisions are made in assemblies where the community members participate. Simón Pedrazas was a member of the committee for years, rotating through different roles: “I was already on the committee, because we have an organized committee there, and I’ve been working on it for many years, in different capacities.” But he was just one among several representatives.

They also had to educate people about financial sustainability.

“At first, the communities always said that everything they generated was for their own benefit, and they didn’t distribute any of it for sustainability. It took us a while to make them understand that.” It took years to convince them that part of the income had to be reinvested in maintenance. However, that learning process ensured that the model could sustain itself.

The model is now being replicated. Two weeks ago, communities from Torotoro visited the reserve. “‘How does this work,’ they ask, ‘so that this can work? I want to do the same there,’” says Guido. The transferable elements: community training methodologies, participatory monitoring protocols, collaborative frameworks that balance scientific rigor with local autonomy, community ownership structure, and transparent distribution of tourism revenue.

Twenty years later, that local legitimacy has translated into regional replication. In Tarija, after the poisoning of 34 Andean condors in February 2021, the community of Laderas Norte decided to create the Quebracho and Condor Natural Reserve. The municipal law was passed in August 2023, seeking to preserve condor nesting areas and promote community-based tourism as a source of local development. The tragedy became a catalyst for conservation, using the Omereque model as a reference.

Armonía has worked on birdwatching tourism development strategies in the Madidi-Pilón Lajas-Cotapata Corridor, promoting training for birdwatching guides and strengthening local economies based on conservation.

Institutionalization progressed gradually. Between 2019 and 2022, an Action Plan for the Conservation of the Red-Fronted Macaw was developed with the participation of the Ministry of Environment and Water, departmental governments, municipal governments from 12 jurisdictions where the species lives, the Armonía Association, the Natura Bolivia Foundation, and representatives from 15 rural communities. The plan establishes conservation strategies through 2030, although funding remains insufficient.

The limits of a community-based approach

The model has cracks. Some structural; others circumstantial. All significant.

The first limitation: a critical dependence on specific leaders. Simón was the first to step up. Marlene has been there for almost 20 years. They are irreplaceable figures.

“There still isn’t enough participation from young people,” Simón admits. “Even though this has worked for many years, we still don’t see young people willing to work as park rangers or guides.”

Migration continues, too.

“With the current situation, many people are still leaving for the cities to make a living,” Simón laments. The dream is to reverse this: “That’s what we want, for it to be truly sustainable and for local people to work, in any capacity, whether as park rangers, guides, or even for the women, and young people too, who can work in kitchens or cleaning. So that people don’t migrate to other places.”

But the reality is that tourism revenue, while significant by local standards, doesn’t compete with urban wages. A park ranger earns between 1,500 and 2,000 bolivianos a month—less than $300. A construction worker in Cochabamba can earn twice that.

The second limitation is vulnerability to external shocks beyond community control. The pandemic brought income to a standstill for two years. The political blockades of 2024 significantly reduced visits.

“There are many problems with the country’s situation—the gasoline shortage, the blockades—and that perhaps weakens us a bit, preventing tourists from coming,” Simón explains.

Guido confirms: “One of the biggest problems we have faced has been the instability of our country due to the poor conditions offered to foreign tourists, especially, and also the social conflicts in our country. I know that all of this does not depend on us, on the communities, but rather on a national character.”

A third limitation is that the model cannot address structural threats to the habitat. Climate change is hitting the dry valleys hard; rivers are drying up; vegetation is dwindling; natural regeneration is slower.

“There has been overexploitation of the vegetation due to the amount of livestock, perhaps uncontrolled and extensive, which has made the habitat increasingly impoverished. And to that we add the issue of climate change, which is hitting this area harder,” Guido says.

The community reserve protects a small area. But the macaws need larger territories.

“The habitat is still very critical for this species, and we have to work hard to protect certain areas that are key for this species, but why not also think about restoring certain areas?” Guido says. “Because it’s going to be very costly, but we have to do it—because if we don’t, and we continue at the rate at which habitat is being destroyed, it’s going to be very difficult in five or ten years. It’s going to be very difficult for the red-fronted macaw, as well as other species in the valley area, to survive.”

A fourth limitation is that the conflict between agriculture and conservation is not resolved. It is managed.

“Lacking food, many bird species, including the macaw, affect farmers’ crops, corn, and fruit trees,” Guido says. “And we have to consider both the farmer’s side and the wildlife’s side. We can’t just look at one side; we have to look at both. This triggers another problem: the conflict between biodiversity and local farmers.”

The current solution—producing corn and peanuts specifically for the macaws—is a band-aid. It works. However, it requires constant work and doesn’t eliminate the underlying problem: an impoverished habitat that forces the birds to seek food in crops.

A fifth limitation is that the model is intensive in social capital. It requires communities with a certain level of cohesion, organizational capacity, and a willingness to collaborate among multiple families.

“We, as a sub-central, are made up of three communities: San Carlos, Amaya, and Perereta,” explains Armin. Achieving consensus among three communities for each important decision is complex. Not all communities have this capacity.

A sixth limitation is that the scale remains small. The reserve protects a minimal fraction of the species’ total distribution range. The 1,160 macaws recorded in 2021 are scattered across four departments. The Frente Roja Community Nature Reserve protects only one of several critical nesting sites.

“We have three key areas for working on the conservation of the red-fronted macaw,” Guido explains. There’s the Caine River in Torotoro, where they nest in sandstone cliffs; he Mizque River here in Omereque, with cliffs up to 80 meters high; and El Palmar in Chuquisaca, where the macaws exhibit an extraordinary interdependence. There, they nest in the Parajubaea torallyi, an endemic palm tree that grows up to 3,500 meters above sea level, higher than any other palm tree in the world. One unique species nesting in another unique species. If one disappears, the other loses a critical ally.

One final limitation is the rigorous evidence is lacking regarding the reserve’s direct impact on the 43.7% population increase. The 2021 census measured the total population across the entire distribution range, not just within the community reserve area. It is impossible to isolate how much of the increase is specifically due to the Omereque community model versus other factors such as decreased illegal trafficking nationwide, conservation efforts in other areas, or natural variations in reproduction rates.

However, the sustained commitment of local communities to protecting the species represents an undeniable positive factor in the population trend, especially considering that these three communities harbor 41.6% of the total population of the species in the Mizque River basin.

Guido is honest about this: “That number is still quite small for a population, for a species that is unique in the world.” The conservation work is far from over.

What’s left to do

It’s three pm in the valley. A trail winds between sandstone cliffs, one that park rangers have traversed thousands of times over two decades. The Mizque River is running strong this year. The season’s abundant rains keep it flowing, carrying stones and eroding the banks. A giant rock in the middle of the riverbed marks the water level. The locals point to higher marks on its surface: “It used to reach this high every year. Then it would dry up for months on end. Now, we don’t know what to expect.”

Up above, in the crevices of the cliffs, pairs of macaws come and go from their nests. These are the same crags where, 30 years ago, community members climbed with slingshots to scare them away.

“Before, we killed them with arrows,” recalls one of the elders. “Now we protect them.”

The story of the red-fronted macaw is not a complete success story. It is fragile progress in a brutal context. From 807 to 1,160 individuals in nine years. From the first lone park ranger to a model that other communities visit to replicate. From communities that killed them, to communities that protect them.

“I’m going to continue supporting them in any way I can,” Simón says before returning to San Carlos. It’s not an empty promise. It’s a declaration from someone who spent 22 years learning that his destiny is intertwined with that of a large, red parrot he once considered a pest.

In the shelter’s kitchen, Marlene prepares dinner. She’s been doing this for almost 20 years.

“Sometimes we want it to grow more, for more people to come and work,” she says, stirring a pot. “Before, very few people came. Now, in recent years, quite a few have started coming.”

Outside, a flock of macaws crosses the valley. The communities protect them. The model works. But it depends on specific people who are aging without clear replacements. And on tourists continuing to come. And on the rivers not drying up completely. And on threats that no one here can control.