Náhuat, one of El Salvador’s indigenous languages, is at risk of extinction—as are 38% of all indigenous languages in Latin America and the Caribbean. Journalist Diana Hernández chronicles an effort to conserve Náhuat in a story produced with one of the 2024 Reporting Grants from Latin American Solutions Journalism Fund, an initiative of El Colectivo 506. This piece was published by Revista Elementos on Nov. 18 and has been adapted for co-publication on our site.

In 2020, while he was quarantined at home, Jonathan Rivas—a migrant from El Salvador who grew up in the U.S. state of Maryland—decided to spend part of his free time learning Náhuat, one of the pre-Hispanic languages of his native country.

His interest led him to meet Héctor Martínez, a Náhuat teacher who created Timumachtikan Nawat (Let’s Learn Náhuat), a platform that offers online resources for teaching and learning the language through online tools such as YouTube and Instagram.

“Well, I was looking for something to do during the pandemic. I think a lot of us were in the same situation, right? I always make the same joke: a lot of people signed up to learn how to make sourdough bread, and I was curious about learning a new language. I have always liked languages, and I was always very curious about our own language, about our own roots, right? For me, being from [the department of] Usulután, even the name of our department is derived from the Náhuat language. I started researching online, on Google, what would be the best way to find a school. That’s how, in the beginning, I met Héctor.”

Náhuat is a Salvadoran mother tongue, with approximately 200 native speakers. The average age of those speakers is 70, most originating from Santo Domingo de Guzmán (in Náhuat, Witzapan, or river of thorns). This town is 80 kilometers away from San Salvador, the capital of El Salvador.

These statistics place Náhuat at risk of extinction. Such is the status of 38% of the indigenous languages of Latin America and the Caribbean, according to the a study carried out by the Ibero-American General Secretariat.

After Jonathan learned these hopeless figures in Héctor’s classes, he invited his friend Efraín Zelaya to take Náhuat classes. Later, they became the first donors of Timumachtikan Nawat, which had already set up social media accounts, and joined the platform team. Together, the three of them—Jonathan, Efraín, and Hector—founded Ne Ichan Sefoura (The House of Sefoura) to ramp up the teaching of Náhuat.

But more was needed. They began to think about how to make the learning process more inclusive: in El Salvador today, very few institutions teach this language. Those that do often have limited schedules and high costs which, according to the three co-founders, sometimes drains motivation from people who might want to learn.

Héctor says he knew that interest in Náhuat did exist, and that the first step should be to create an affordable program. The initial strategy was to offer free classes through scholarships. The program began with a small group taking the introductory level. This was the starting point of a project that seeks to break down economic barriers and revitalize an ancestral language.

““…I saw that [the teaching of] Náhuat was becoming, in a certain way—perhaps the word ‘privatized’ is a bit strong, but that is what I perceived. I said: ‘Well, even though there are some courses within these institutions, there are very few people here. They should be full. This is an important issue.’ But I started to think: ‘The cost that this represents for the majority of Salvadorans is high. Not everyone is going to stop doing certain things or buying certain things to invest in cultural education.’ …That was how I got interested in doing something different, something accessible, something that could reach people and that didn’t have a price tag. That also motivates people to learn.”

The challenge of conservation

What factors have brought Náhuat to the brink of extinction in a country with more than 6 million inhabitants? The problem has roots in a traumatic historical episode.

On Dec. 2, 1931, Maximiliano Hernández Martínez took power after a coup d’état, in the midst of an economic crisis caused by the collapse of coffee prices. The political situation led to an insurrection on Jan. 22, 1932, when thousands of peasants, mostly indigenous, took place in western El Salvador. The army quickly retaliated and crushed the uprising; anywhere from 10,000 to 30,000 people are estimated to have been killed.

One of the leaders of the uprising was José Feliciano Ama, a indigenous campesino from Izalco. After the insurrection, he was hanged by the military forces, dressed only in his sala and kutun (shirt and pants in Náhuat), in full sight of local residents.

Izalco was the epicenter of this event—which, scholars agree, reached levels of ethnocide. Some of the victims in this Salvadoran district were buried in a common grave located in the ruins of the Church of the Assumption. Today, this place is known as El Llanito.

The massacre marked the beginning of a process of marginalization and repression of indigenous identities, primarily of the Izalcos, including their language.

Since that massacre, indigenous communities faced a policy of cultural repression that forced them to abandon their customs and language to avoid being persecuted. Náhuat, in particular, was marginalized and silenced for fear of reprisals. Furthermore, the lack of linguistic protection policies for decades contributed to the progressive disappearance of the language.

The research of anthropologist Mariella Hernández Moncada shows how, indigenous peoples have been made invisible throughout history, starting with violence and dispossession during Spanish colonization. Diseases such as malaria, smallpox, measles, yellow fever, and tuberculosis reduced their population by up to 80% in some areas. In coastal areas, the indigenous population practically disappeared. The communities that survived were grouped in the areas that today correspond to the departments of Ahuachapán, Sonsonate, La Libertad, San Salvador, La Paz, and Morazán. These communities were forced to integrate into the colonial system, which used an estate structure of haciendas and encomiendas as a form of control and exploitation.

Indigenous communities were not recognized by the Constitution of the Republic of El Salvador until 10 years ago. In 2014, Article 63 of the Constitution of El Salvador was modified to include the following text: “El Salvador recognizes Indigenous Peoples and will adopt policies to maintain and develop their ethnic and cultural identity, worldview, values and spirituality.”

El Salvador also has a Culture Law, approved in 2016. Article 9 of this law reads: “Spanish is the official language of El Salvador and constitutes part of the assets that constitute cultural heritage, which equally include the languages of indigenous peoples, whether alive or in the process of being rescued.”

However, when it comes to rescuing Náhuat, very little has been done. As Héctor points out, instead of rescuing the language, authorities are excluding the elders who are the bearers of this valuable knowledge.

““Like all the other previous administrations, they always, let’s say, make it look like they are doing something, but more than anything, if you pay attention, they are on specific dates, right? On Náhuat Language Day, Mother Language Day, Indigenous Women’s Day. Generally, what they do is to publish something, some video or some presentation, and, well—that’s it, right? But, really, there is no deep work that is being done on the language itself. There were people who might say: ‘Ah, but they have released two books in this current administration that are quite important, right?’ One of them was ‘The Little Prince,’ but when you start to find out who did the translation, well, he’s not a Náhuat speaker. So, yes, we are trying to project Náhuat, but we really forget the most essential part, which would be Náhuat-speaking elders.”

Shimutalikan! Sit down!

Although the State is responsible for protecting indigenous culture and roots, it has not taken significant measures to do so, according to anthropologist Julio Martínez. He says that while some actions have been carried out, they have been mainly symbolic and lack depth or continuity; he characterizes official efforts as superficial, since they do not address the true needs for cultural preservation or the comprehensive revitalization of Náhuat. An example is the initiative of the Salvadoran government in 2018 that trained 70 teachers in teaching Náhuat and cultural identity, but did not then receive adequate follow-up.

Julio argues that there should be at least one Náhuat teacher in each of the more than 6,000 public schools in El Salvador, which would reflect a real commitment to the revitalization of the language.

The Salvadoran government recognizes Náhuat Language Day, the International Day of Indigenous Peoples, and the Day of Indigenous Women. However, unlike countries such as Mexico and Chile, where the last bearers of native languages are considered living treasures and effective strategies are implemented for their protection and well-being, the country has not provided support to its Náhuat speakers.

While Mexico and Chile offer benefits and programs to improve the quality of life of the bearers of ancestral languages, in El Salvador, the last 200 Náhuat speakers live in conditions of poverty, without access guaranteed basic services. Advocates of Náhuat conservation say this reflects an insufficient commitment on the part of the State in the preservation of its indigenous culture and language.

According to Julio Martínez, providing protection to these people would not represent a burden for the Salvadoran government, but rather an opportunity to strengthen the national identity and sense of belonging of citizens—since people who connect with their cultural roots often enhance their love of country more and feel greater ownership of their history and society.

Official abandonment has been consistent across administrations. However, Héctor did not lose hope—nor was he afraid to propose a national project for the teaching of Náhuat. In 2019, with the arrival of a new administration, he and his collaborators attempted to establish contact with Suecy Callejas, who at that time held the position of Minister of Culture. Although they were not able to speak directly with her, they were delegated to Erick Doradea, then director of Territorial Networks, who received the proposal. His position was key, as he managed issues related to indigenous communities.

Despite the effort and the presentation of a detailed project, the outreach ended in frustration.

“We brought our best ideas,” Héctor says. However, after the meeting, they were told they would be contacted—and they never were. The proposal is still awaiting a formal response.

These types of situations highlight the lack of follow-up on projects that impact historically marginalized communities such as indigenous peoples, who are still waiting for a firmer commitment from cultural authorities. A clear example is the decision of the Ministry of Education in February, which separated itself from the Kunas Nawat, schools dedicated to teaching Náhuat to children between 5 and 8 years old. In their place, the ministry proposed “Language Immersion Nests.” However, to date no clear information has been provided on how this new initiative is being implemented.

Timumachtikan Nawat

What began as the dream of two young people to reconnect with their roots has grown into the largest digital repository of Náhuat. Timumachtikan Nawat (Let’s Learn Náhuat) now has more than 22,000 followers on Facebook and more than 3,300 on Instagram.

The House of Sefoura has awarded scholarships to more than 700 people as a result of 10 application processes since 2020. The beneficiaries have taken classes at three levels and receive a diploma at the conclusion of each one. As a final project, they write an article on a topic of their choice for Wikipedia in Náhuat. The students have been key in the preparation of more than 300 articles in Náhuat, strengthening the presence of the language on digital platforms and contributing to its revitalization. The Wikipedia effort is still in the “incubator phase,” as more than 500 articles must be shared in order for Wikipedia to recognize this wiki in Náhuat worldwide.

According to the VII Population Census and the VI Housing Census, carried out in 2024, only 1,135 people speak Náhuat of the more than 6 million inhabitants in El Salvador today. This figure includes 200 native speakers, as well as “neo-speakers,” those who have learned the language through their own initiative. Efforts such as Timumachtikan Nawat and Ne Ichan Sefoura have contributed significantly to improving these statistics. However, as Jonathan Rivas recognizes, the numbers are still limited and the road ahead is long.

“Seriously, I never thought we would reach so many…. but if I start to analyze now, we are still very few, that is, in the sense of the whole Salvadoran population. While we have affected thousands, we have only done a bit. I think we could start doing a lot more.”

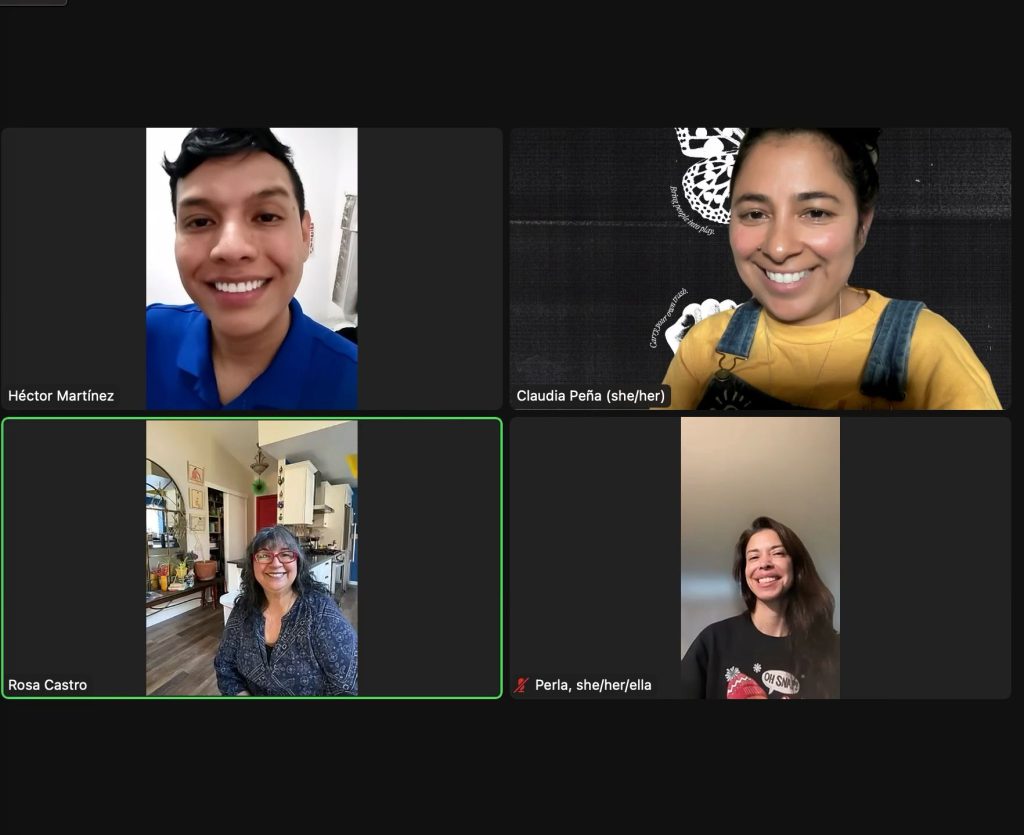

In 2023, new efforts were added to the project. Nathalia Mazariegos and a group of three Salvadoran women living in California and working under the name “Tikyulwepat ne nawat” (“Let’s return the heart to Náhuat”)—Perla Aragón, Claudia Peña and Rosa Castro—joined the initiative as donors.

They recognized that this effort not only preserves the language, but also promotes the well-being of indigenous communities, fundamental to community health and the environment. Thanks to their participation, the Timumachtikan Nawat project incorporated a level of Náhuat teaching in English. The current teacher of the Náhuat/English level is Valery Santillana, a student of the three levels in the virtual Náhuat school and now a teacher in this project.

“You know, Hector is a great leader, so he takes the initiative to do a lot of things. We talk about them, but the truth is that he is the leader in all aspects… He is someone with whom you can think and perhaps have an exchange of ideas, so in that aspect […] (04:50-5:22)(5:49-6:23) I am glad that what we have been able to support is that Apple has opened up more opportunities for me to do more classes.Now there are classes not only in Spanish, but also in English. It is very nice to see that Valeria has students from Canada and various parts of the United States. It is a nice way to bring us all together: a collective, a community.”

Their students have also been key in the effort to write more than 300 articles in Náhuat for Wikipedia, strengthening the presence of the language on digital platforms and contributing to its revitalization.

One of the most significant achievements within this project has been the creation of the first Náhuat dictionary written by a Náhuat speaker, Nantzin Sixta Pérez, an 83-year-old indigenous woman from Santo Domingo de Guzmán. The dictionary, titled “Yultajtaketzalis” (“Words of the Heart”), is a reflection of the worldview of the indigenous peoples of El Salvador, and has become an invaluable testimony to the country’s cultural identity.

Sixta Pérez, who has been a teacher for four years at House of Sefoura, has left a deep mark on the fight to sustain this ancestral language, which is still alive after resisting more than 500 years of colonization. Sixta says that because participating as a teacher in this project has allowed her to speak more Náhuat, the experience has made her “stronger.” Every day, she feels more proud of her language.

To date, more than 1,000 copies of the dictionary have been distributed free of charge, and presented at four events: the first in Witzapan, Santo Domingo de Guzman, the cradle of the Náhuat language; then at the JJosé Simeón Cañas University; and later in two districts of Cuscatlán, El Salvador (Cojutepeque and Suchitoto).

This project was possible thanks to a community drive that lasted four months, with the participation of more than 200 donors. It also received the support of the AES company and the Make Art Not War Foundation, demonstrating the power of collective work in the preservation of cultural heritage.

Náhuat, not Náhuatl

One of the important aspects of the dictionary was its registration. Salvadoran Náhuat is different from Mexican Náhuatl. Although they are sister languages, the variations in their dialects and the differences in many words mark a clear separation between the two and give each of them their own identity.

Despite this, for the International Standard Book Number (ISBN) registry, after a long process of filling out information, the team behind the dictionary was not allowed to register the book under the Náhuat language without a final “l.” However, they did not give up, because to include that “l” would detract from their work and the identity of the language in which the dictionary was written. Through a project, they managed to register the book at the ISBN agency in Los Angeles, California. While the ISBN process in El Salvador had taken several months, it took about a week in the United States.

Turn it around

According to anthropologist Julio Martínez, the technological avalanche is contributing to the disappearance of our own culture, but projects such as Timumachtikan Nawat are “turning [this trend] around” by using technological tools in their favor. This represents an innovation in the traditional teaching of Náhuat.

However, since it is an individualized project, unsupported by a state policy, these advances could be short-lived.

“Again, I wish that it was not an individualized effort, good as it may be, but rather a state policy. Because individual efforts are beautiful, but if they are not state policy, they will remain just that: a beautiful, applaudable individual effort, but without impact. I think you have to learn from that and then not be like a drizzle that happened one afternoon, but see yourself as the sea that covers everything.”

Like Julio, Jonathan Rivas believes that the learning Náhuat should be a right for Salvadorans.

“From wanting to grow in the language and for it to be something more accessible, my mentality also began to change a lot, especially in making the dictionary. Today, I don’t see it as something in which we have to look for it to learn it. For me, this should already be a right that we have, and not a privilege—our right to learn the language. If you take, for example, a country in which I also spend a lot of time, Paraguay, they use their Guaraní language, right? They even use it officially. In government documents, you have Guaraní on par with Spanish.”

Last September, Timumachtikan Nawat was recognized by the Central American Parliament with the honor “Heroes of the Indigenous, Black and Popular Resistance to the Bicentennial.” This was a significant achievement for the project.

This initiative has directly involved Náhuat-speaking elders in teaching within its platform, recognizing their fundamental role in the preservation of the language and traditions. Aware of the cultural wealth that still remains to be protected, they have also organized virtual workshops on various aspects of Salvadoran Náhuat culture, such as traditional clothing, artisanal flavors, Náhuat mythology, music in Náhuat, and the culture of corn, among others.

These efforts not only preserve the language, but also keep alive the ancestral practices and knowledge that are an essential part of indigenous identity.