In this rural area of Peru, women organized in community networks defy fear and state indifference to bring justice and hope to victims of gender-based violence. Journalist Scarlet Timana tells the story of this program in this piece, created with a grant from the Latin American Solutions Journalism Fund, an initiative of El Colectivo 506, with support from the InnContext Agency InnContext Agency of the Avina Foundation. This work was published by Norte Sostenible on May 2, 2025, and was adapted here for co-publication. Please note that the English translation has been modified for clarity and regional context.

The wooden door is barely holding: the humidity has eaten away at its base, and the rusty nails hang on for dear life. This is not a house, but the community hall in a dusty human settlement on the outskirts of Piura, a hot region in northern Peru. There, sitting on a wooden bench, Ana* hugs her six-year-old daughter tightly while, for the first time, she dares to say aloud what she has kept quiet for more than a decade: her partner hits her.

Ana chose to tell this story not in a police station, but here, in this space. In front of her, a community defender tells her: “You are not alone.”

In Peru, gender violence is not an isolated event. According to the Demographic and Family Health Survey (Endes) , in the first half of 2024, 52.5% of Peruvian women between 15 and 49 years old suffered some type of violence at the hands of their partner. The majority of these women remain silent. Fear, distrust in the judicial system, and lack of access to adequate services prevent many from reporting the abuse. However, faced with this gloomy panorama, a response has emerged in Piura, from the margins: a network of women who weave protection and justice from below.

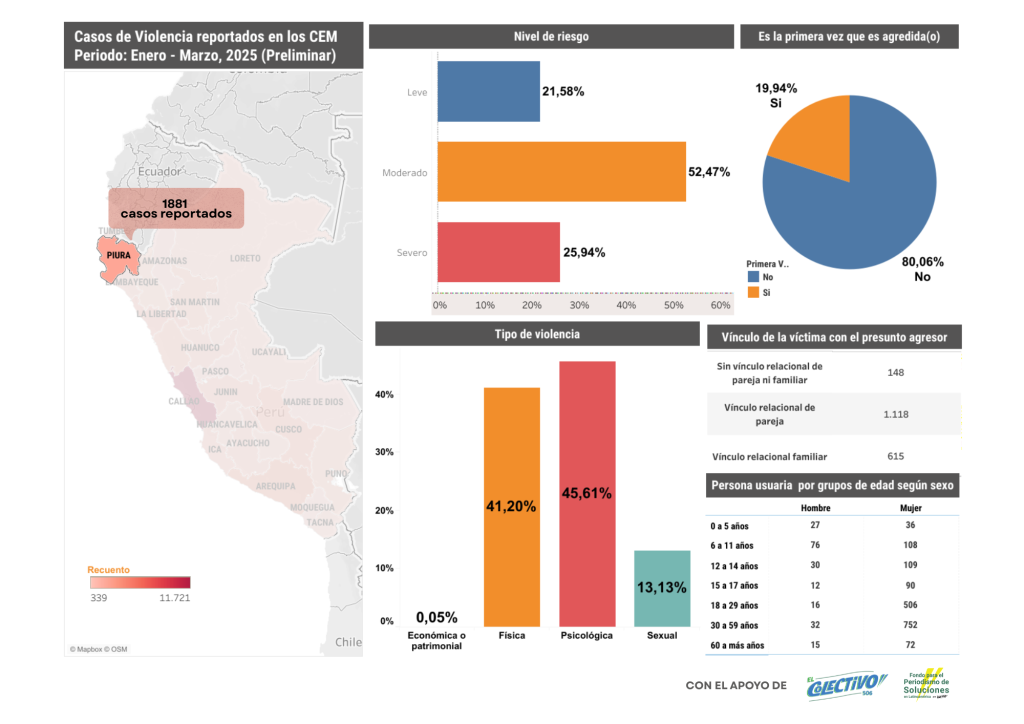

They seek to change these harsh statistics on violence against women. Between January and March 2025, the

Women’s Emergency Centers (CEM) in Piura responded to more than 1,800 cases of violence. Of these, 46% were cases of psychological violence, 41% physical violence and 13% sexual violence; most of the victims were between 18 and 59 years old. But these reported numbers barely scratch the surface. In the hamlets and human settlements of this region, fear, distance, institutional re-victimization, and a lack of legal and psychological support make many choose to remain silent.

In addition to violence, the Piura region faces other critical gender gaps: teenage pregnancy, illiteracy, limited political participation, and unequal access to natural resources. Faced with this, the Regional Gender Equality Plan (PRIG), lead by Regional Social Development Management of the Regional Government of Piura, seeks to make these inequalities visible and promote concrete actions from the state and civil society.

The silent fight of community defenders

Starting in 2018, in Piura, a silent but firm movement has begun to transform the lives of hundreds of women. These are the eleven women’s community networks, a project promoted by the Cutivalú radio station. This media organization has a social mission and a focus on human rights; it seeks to provide communication, advocacy and community support. As part of its social commitment, Cutivalú took on the fight against gender violence, identifying it as an urgent structural problem in this Peruvian region.

With the technical support of the Association for Research and Specialization on Ibero-American Issues (AIETI), as well as financing from the Regional Government of Andalusia (Spain), the project “Women weaving networks for a life free of violence and discrimination” was launched seven years ago. Since then, the project has created spaces of resistance and empowerment in districts such as Veintiseis de Octubre, Chulucanas, La Matanza, Tambogrande, and Piura.

These networks are not simple support groups: they are organized structures with presidents, boards of directors, and a minimum base of 25 members recognized through municipal resolutions. Their legitimacy allows them to coordinate with institutions such as the police, the Prosecutor’s Office, the Women’s Emergency Centers, and municipalities. They are, in essence, a solid social fabric that supports and transforms victims of violence.

The defenders receive comprehensive training from Cutivalú in alliance with specialists from public institutions and partner organizations such as the Flora Tristán Peruvian Women’s Center. They learn about psychological first aid, reporting routes, legal procedures, and communication strategies. “We work a lot on self-esteem, self-confidence and soft skills. Many have suffered violence and need to heal before helping others,” explains Ortelia Valladolid Brand, the project coordinator at Cutivalú.

The impact of these networks is visible on various levels. First, they’ve noted an increase in complaints: women are no longer alone, and they dare to speak out. Second, they’ve improved inter-institutional coordination. The networks not only apply pressure, but also empower officials within the justice system to act with a gender perspective.

More recently, the networks have also achieved the inclusion of men in community processes. “In districts such as La Matanza, we are already including men in workshops on masculinities and co-responsibility,” says Valladolid. This shift is the result of one of the lessons learned by the project: over time, network leaders understood that it was not enough to empower women, but that it was also key to work with men to change deeply rooted cultural patterns such as machismo and generalized violence.

Economic empowerment is also part of the process. Many women do not report violence because of their economic dependence on the aggressor. Therefore, the networks promote women’s autonomy by offering training in entrepreneurship, job placement, and access to seed capital, with the support of entities such as Manos Unidas and Taller de Solidaridad.

However, the challenges are great. There are still municipalities that do not formally recognize these networks, and it’s common that institutions fail to respond with the urgency that these cases require. Resistance also comes from intimate relationships: “There are women who cannot actively participate because their partners do not give them permission, or they do not understand the value of their community work,” says Valladolid.

To guarantee the sustainability of the project, the goal is for the networks to transcend, becoming part of local public policy.

“We want to ensure that, when the Cutivalú intervention ends, the Piuran municipality continues to support them,” says Valladolid. In the district of La Matanza, for example, the municipality has already begun to assume part of the support for the networks. That is a great advance.

Yolanda: the strength of a shared story

In the Veintiseis de Octubre district, one of the youngest and most vulnerable in Piura, a group of women has woven a silent but firm network. It’s called the “Support network for victims of violence in the 26 de Octubre district”, an organization made up of communal leaders, neighborhood associations, and lieutenant governors.

Yolanda López Chira has a dual role as vice president of the district network in Veintiseis de Octubre, and president of the provincial network, called Unidad por el Cambio Piura (Piura United for Change). She is also a survivor. For 15 years, she suffered physical, psychological, sexual and economic violence.

“I couldn’t paint, work, or wear the clothes I liked. If I went out to sell, I was beaten,” she recalls. The attacks occurred even at night, when everyone was sleeping. “I didn’t know that that was violence, too.”

The first time she reported the abuse, she was told at her district police station: “You must have done something to your husband to make him hit you.”

But one day, in front of the mirror, looking at her beaten face, she decided that she couldn’t take it anymore. She entrusted herself to God, left with her children, sought support, and today leads a network with more than 35 active defenders.

Thanks to the support of the project, some women community leaders accessed seed capital to launch new enterprises. This capital did not take the form of cash, but rather basic supplies such as rice, sugar, oil, tables, chairs and utensils so that they could start selling food or sweets.

“I cook every weekend. I sell to continue helping other women who also want to empower themselves,” says Yolanda. Now her business is called De todo para ti (Everything for you). What was previously an occasional sale became a dignified, shared workspace that’s expanded to offer additional jobs.

“It wasn’t just for me. I put two more ladies to work. They already sell sweets at a school. They are getting ahead,” she says proudly.

Networks that change lives

Thanks to the support of the project, some women community leaders accessed seed capital to launch new enterprises. This capital did not take the form of cash, but rather basic supplies such as rice, sugar, oil, tables, chairs and utensils so that they could start selling food or sweets.

“I cook every weekend. I sell to continue helping other women who also want to empower themselves,” says Yolanda. Now her business is called De todo para ti (Everything for you). What was previously an occasional sale became a dignified, shared workspace that’s expanded to offer additional jobs.

“It wasn’t just for me. I put two more ladies to work. They already sell sweets at a school. They are getting ahead,” she says proudly.

In some districts, the networks organize information fairs, caravans, community theater plays, cineforums, consultancies, and radio campaigns. They have even supported girls who are victims of sexual violence in their own homes.

“The impact is significant, because today, many are no longer alone. They know that there are other women who understand them, who support them,” says Yolanda López.

However, they still face obstacles.

“We do not have materials, transportation, or an emergency shelter,” says Flor de María Pacherres, a Piura defender.

But these shortcomings do not stop them. Despite the lack of resources, bureaucracy and exhaustion, they continue to fight. Yolanda, with a firm voice and open heart, does not plan to take a step back.

“I want my daughters and all Piura girls to live in a world where being a woman is not a risk,” she says. “That’s why we continue. Because every story we save, every woman who dares to say ‘enough’, is a victory for all.”

What these women do without uniforms, without salaries, without spotlights, is community justice. They are networks of hope that support others when the system fails. In this interweaving, they are sowing the possibility of a freer, more inclusive and fair region for all.

What began as a community response to violence is today a movement that transforms not only lives, but also old structures.

*Names have been changed to protect the identity of the sources.