Milagro González Villalobos is always on the lookout for books. She knows to keep an eye out for hidden treasures. She’s the librarian and information manager at the Nuestra Señora de Fátima School in Cartago—a school that gives priority to at-risk students. In a country experiencing a crisis in reading comprehension, she searches for stories that she can share with her students, stories that will make them feel represented, stories that will spark conversation.

The Brothers Grimm? Hans Christian Anderson? Not her highest priority. Because Milagro is ever mindful of the particularities of her community, which is at great risk of weather-related disasters, she decided to use a book on that subject. She chose a book about the rains and downpours of the tropics, created by Costa Rican hands.

Milagro’s urge to find books close to the experiences of her students is aligned with studies in other parts of the world. Several academic publications in the United States have indicated, again, and again, and again, that if African-American children and youth have access to books that reflect their culture and reality, they’ll develop better reading skills and greater pleasure in reading.

“Both reading achievement and reading motivation are affected by the availability of literature that offers children ‘personal stories, a view of their cultural surroundings, and insight on themselves,’” reads a 2009 publication by Hughes-Hassell, Barkley and Koehler. “With repeated exposure to engaging literature in which children of color find characters and a context that they can recognize and to which they can relate, reading is more likely to be an appealing and successful activity.”

This can affect not only students’ motivation, the study says, but also their comprehension: “The African-American students’ reading comprehension and recall were more efficient and accurate when text and illustrations in reading materials reflected themes consistent with their own sociocultural experiences, rather than when they represented white images and culturally distant themes.”

Does this apply to Costa Ricans, to other Latin American countries, and to indigenous groups? If they have access to books and stories closer to their own experiences, will they read more and better?

The simplified answer is yes. Although access to books—any book—remains the biggest challenge for many learners in Costa Rica, students do benefit from feeling represented in the places and people they read. And some successful efforts to promote reading, here and elsewhere, combine both: access to books, and the creation of books with local content.

What happens when your only book tells the story of your own community?

One initiative that has put this idea to the test for Latin America is Chile’s Fundación Cámara Mágica, led by Cecilia Enriquez, founder and Executive Director.

Although the foundation was created in 2011 to create audiovisuals about the diverse cultural groups and realities within Chile’s expansive terrain, it shifted its focus in 2020 towards the creation of children’s books.

“[We are] gathering cultural stories that have never been set down on paper, but that are very well known [locally],” Cecilia explains. “Then we make them into books with a local writer and a local illustrator so they have the flavor of the place. We sell these illustrated children’s books with the promise that we’ll use the profits to reprint and give these books for free to children in rural areas close to the origin of the story.”

Since 2020, the foundation has delivered more than 4,000 books to various communities in Chile, including the Chiloé archipelago, in Chilean Patagonia, and Rapa Nui, known as Easter Island.

There, in Rapa Nui, which Cecilia describes as “the most isolated place in the world,” they developed a bilingual Spanish-Vanaŋa Rapa Nuibook, which was delivered to 1,000 children on the island between preschool and third grade. The objective of this book was to reassert the value of the indigenous Rapa Nui language, which is being lost.

“When we started, only 11% of the children understood their language. That has now increased,” says Cecilia. “And the act of speaking the Rapa Nui language creates a feeling of pride. It’s something that must be done.”

Chilean Patagonia has also experienced this vindication of local culture.

“In an indigenous school, the teacher told me: ‘We are all Maqui [referring to the protagonist from the Cámara Mágica book], because we all have a grandmother who weaves and has taught us things about wool,’” Cecilia recalls. “It strengthens the collective imagination where not only the children, but also the entire community, recognize themselves. It gives to all the stories equally.”

For Cecilia, writing books that are culturally relevant puts Latin American culture on the same level as the European stories that have long dominated children’s books: “Castles, princesses, dragons—they are things that I have never seen in Chile or in any Latin American country. So being able to read in settings that are related to their own culture shows them that their culture is just as valuable as any other.”

Regarding the impact of these stories on kids’ interest in reading, Cecilia agrees with North American researchers.

“When we visited the schools with the book, kids would say ‘This is a lichen, and I found out about lichens when I went to the forest with my dad!’ That immediately generates an interest in reading. For the kids, these are elements that they live with every day, but that have never been … valued. Here they are all together in the same text. That generates interest.”

For Cecilia, the impact extends beyond the communities that Cámara Mágica’s stories are drawn from. It also reaches kids in other parts of Chile who, through the books, get to know parts of their country that they’ve never visited: “For children who are not from the place, it allows them to get to know it in depth. Children who have never seen the ocean, for example.”

If it works in the United States and in Chile, will it work in Costa Rica?

So what happened when Milagro, the librarian at the Nuestra Señora de Fátima Cartago School, found a book that might resonate with her fourth grade students?

Because of the community’s vulnerability to storms, she decided to read them “El barrio de la lluvia (The Neighborhood of Rain),””, from La Jirafa y Yo, a Costa Rican publishing house and a sponsor of this edition of El Colectivo 506.

“It’s a short book, a kind of album, because the illustration itself tells you the story,” explains the librarian. She says that reading this book with her students generated a wave of positive reactions. “It encourages the children to pay attention, because they identify with it so much. They bring up other stories, even from their personal experience—what would I do in this situation, or if that happened. These kinds of activities stimulate them and make them want to come to the library.”

Susana Jiménez had a similar experience. She is a special education teacher at a leading private school in Costa Rica (she asked us not to identify the institution, in keeping with policies). She says that special education educators have few guidelines about what materials to use for literacy, and her students have a broad range of learning levels.

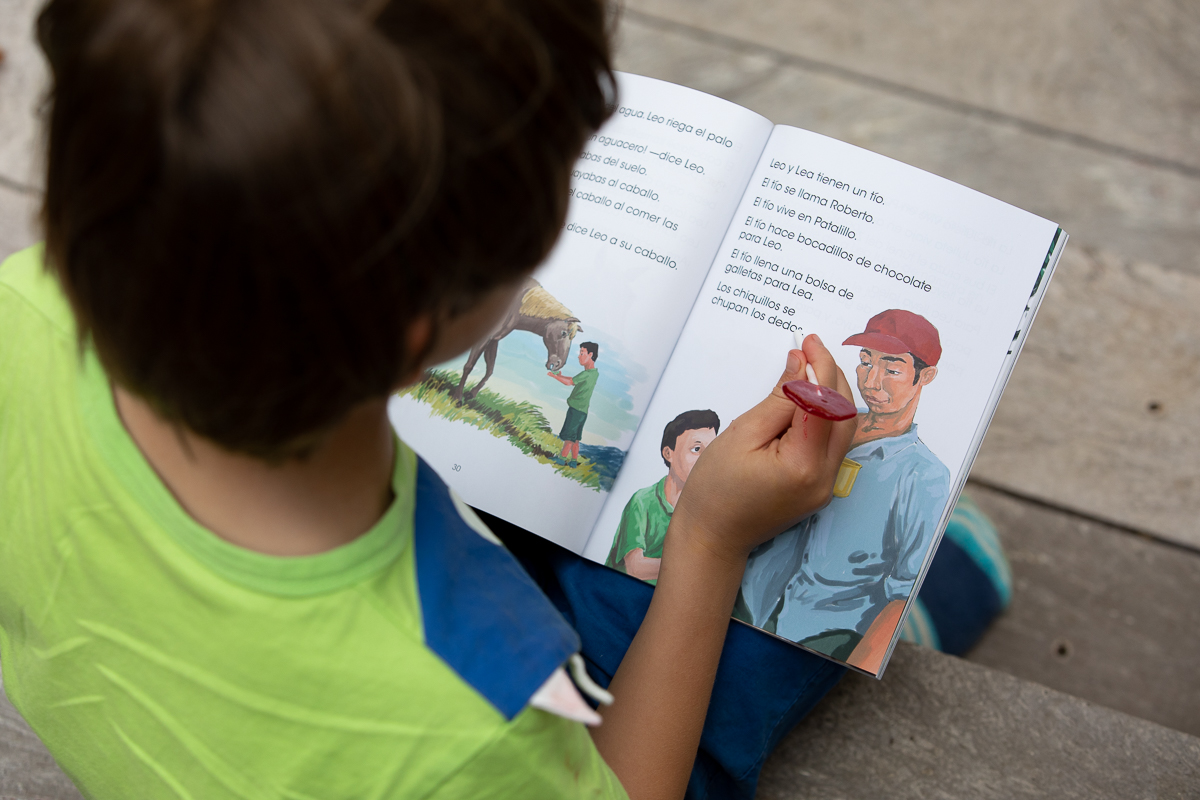

Four months ago, Susana started working with the book “Leo y Lea” from La Jirafa y Yo’s School Collection, which was recommended by a third grade teacher of the same institution.

“It is very well done, because it comes with an increase in difficulty that is totally related to the logical process of literacy—and it’s also close to the Costa Rican reality.”

For Susana, this last point has been very important because it has allowed her to bring her students even closer to reading. For example, she says that one student with Down syndrome loves the beach, so reading about Costa Rican beaches in the book have increased her interest in reading.

Susana also says that for her students, having a book that uses Costa Rican vocabulary is very beneficial. For example, she once used material from South America to teach syllables, and when he is teaching the syllable ‘mi’, the student must associate it with the drawing of a glove, which in those countries is known as a mitón. Since a glove is a guante in Costa Rica, this creates a stumbling block for her learners.

“I can give you thousands of examples like that,” says Susana. “It has been difficult to find exclusive material with our language for reading and for general teaching process.”

She says that’s why it is so important to have textbooks and readings that reflect the Costa Rican reality.

“Actually, it is something that I would recommend for any type of child and at different stages of the literacy process because I feel that it is closely linked to the DUA (Universal Design of Learning)—which says that, to guarantee quality of education, we have to start from the interests of the children and what surrounds the child,” she says. “Starting from the family, the school, the community, the country and then the world.”

According to another U.S. academic publication by Bena R. Hefflin and Mary Alice Barksdale-Ladd, “reading for years and not finding stories that connect closely with one’s own cultural understandings and life experiences is problematic. If teachers continually present African-American children with texts in which the main characters are predominantly white animals and people, it stands to reason that these children begin to question whether they, their families, and their communities fit into the world of reading.”

Once again, educators suggest that this statement rings true for other populations and contexts. One of those voices belongs to Hazel Hernández Astorga—librarian, philologist, founder and general director of the Fundación Leer (Read Foundation)One of the premises underpinning the foundation’s work is that literature must reflect the Costa Rican reality in order to obtain the maximum impact on readers, especially the youngest kids.

For Hazel, culturally significant books are a kind of meeting space.

A foundation project called Violet Books, seeks to help promote gender equality among Costa Rican children. One of the books they use for this purpose is ‘Mo’ by the well-known Costa Rican author Lara Ríos.

“We chose ‘Mo’ because she is an indigenous girl who is part of the Costa Rican idiosyncrasy,” says Hazel, explaining that even if a Costa Rican child isn’t familiar with the Cabécar indigenous population at the heart of the book, there are commonalities that go beyond this.

“Although there is a cultural distance, if there is a rapprochement with the problem and with the feeling of that character—the relationship with the mother, the father, the community, with what she wants to do when she grows up—it is something that a boy or girl from Guanacaste, from the Central Valley, will be able to identify with,” says Hazel.

She sees the same thing happen with another books in the Libros Violeta collection.

“In ‘Palabras atoradas (Stuck Words), [the character] is a girl with dark hair who could represent 50% of the Costa Rican population. Even if you don’t physically identify with that girl, there is a person close to you who looks like her,” Hazel says. “So since I identify with her on a cultural level, I can now go a little further and identify with what she feels, what she experiences, and what she wants to express.”

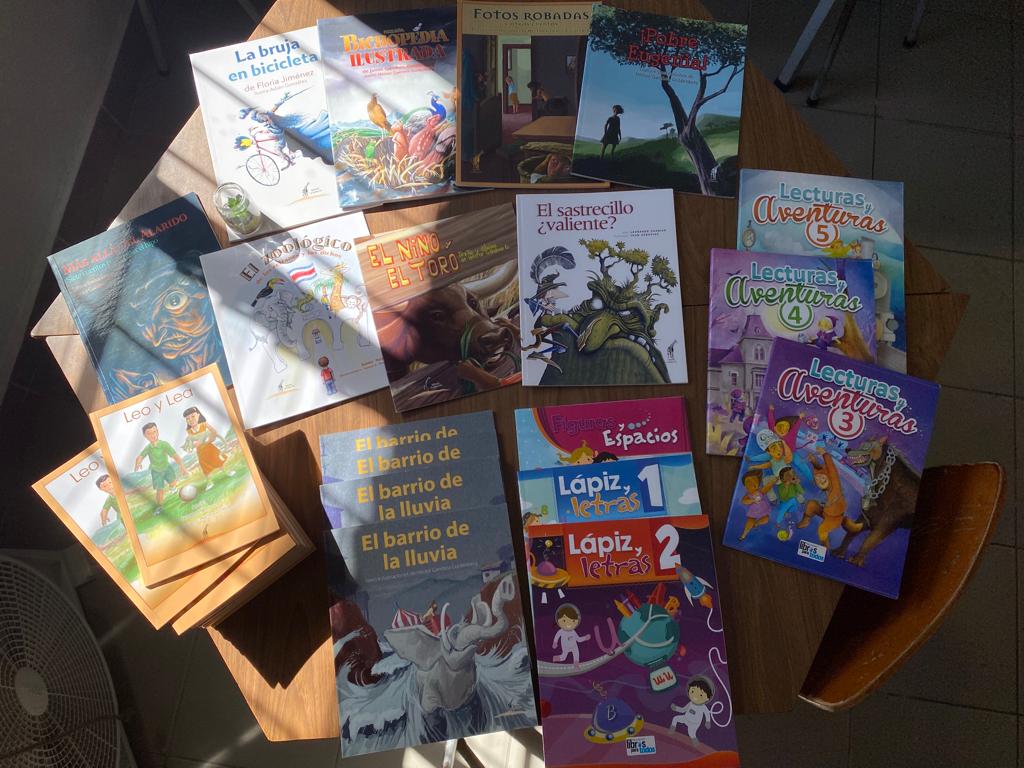

The Fundación Leer is Costa Rica’s representative for the International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY), which every two years presents an Honor List that recommends books for children and adolescents around the world. Although the official list only presents three books per country, the Fundación Leer, which curates the Costa Rican entries, expands the list to eight in its “Guide to Highly Recommended Books for Children and Youth.”

Hazel explains that the books selected for the Fundación Leer and IBBY lists share high aesthetic quality, as well as content that represents the Costa Rican reality.

“Their themes are timely, but they always have that sense of cultural identity,” she says.

On the shoulders of teachers

The great advantage, as these educators demonstrate, is that Costa Rica does have locally and nationally produced books with authentic stories that students can relate to.

However, the task of choosing these books—and obtaining them—falls to the men of each individual teacher.

The Ministry of Public Education (MEP) has a listof recommended books that reflects a diversity of geographies and cultures, but none is mandatory because this would be “opposed to a vision of reading as a pleasant, voluntary and joyful act,” reads the document. Each teacher can choose between the selected readings or create their own material.

Anne Señol, founder of La Jirafa y Yo—a small publishing house that was born more than 15 years ago with the desire to maintain Costa Rican culture in school textbooks—believes that this has certain disadvantages.

“It is important that children know what it is to be Costa Rican, and understand Costa Rican culture,” says Anne. For this teacher of French origin, the MEP made a mistake when it removed Emma Gamboa’s classic “Paco and Lola” from its curriculum.

“There was no pedagogical need to remove it,” says Anne, after acknowledging that the decision was prompted by a review of gender equity in the book. (For example, the classic literacy text includes an infamous scene where the mother and her daughter work in the kitchen—“mamá amasa la masa”—while the father and son read the newspaper.) “They imported books from Colombia and Mexico, and the vocabulary changes. A child who stumbles over decoding the word has a hard time [learning to read].

“The goal [of La Girafa y Yo] was to create books that were totally soaked in Costa Rican culture, not only of the city but of the entire country. And to give [students] books that are calm, that don’t create more anguish than they already have, that speak to them about the cultures of their parents and grandparents,” says Anne.

For Hazel, the problem of eliminating required literature in schools, and not showing more recognition to culturally relevant authors and content, has deeper roots.

“I think it goes a bit deeper, down to the issue of public investment. Thirty years ago there was greater interest in strengthening the education system,” she says. “There was much more interest in promoting editorial production… and in bringing teachers closer to those books. The educational system has been weakening, not only due to the teaching staff, but because more investment is needed and is not happening.”

“For me, even beyond the economic part, every child in Costa Rica should have these books, because right now they don’t have any books at all,” adds Anne, referring to her school collection.

In any case, the reality is that for now, teachers are entirely responsible for choosing books that foster a love of reading among their students. For Hazel, that is why teachers need to be trained in this regard.

“We can read ‘Mo,’ and talk about the indigenous population and how the girl wants to be a dentist, and just stop there,” says Hazel. “But if the facilitator digs deeper, reviews and connects with those people who are receiving the information, they can explore more issues—gender, the environment, among others. That way, the people receiving this information are going to want to ask questions, start to investigate more.

“But let’s go back to the State of Education report: the teaching population, unfortunately, does not have that interest in tackling reading for pleasure. There may be many justifications—time, paperwork—but unfortunately the report says so. They asked [the teachers], ‘Do you read for pleasure?’ and they said ‘No.’”

Susana, as a teacher, makes one last comment.

“I remember, when I was little, in every house there was a copy of ‘Paco and Lola,’ and parents made an effort to read with their children,” she says. “Now there is no book that families feel they have to have. I think that a lot of what has happened has to do not only with the work that is done at school, but also with lack of interest and lack of access to things that parents can do with their children.”

—-

This story for the April and May 2023 edition, “Let’s Read!,” was made possible by the support of La Jirafa y Yo, a publishing house that specializes in producing books for children and adolescents. The editorial is linked to the European School, in San Pablo de Heredia, where it tests its materials. We thank the team at La Jirafa y Yo for their support and for their information and comments about the impact of culturally relevant reading material.