In 2011, my daughter Kami was six years old and in the first grade. Luis Carlos Garza, the then-coach of the Santa Inés School cheerleading team (The Bears), asked Kami’s mother if she agreed that our daughter should be part of the team. We have always supported our children in all the sports they have wanted to pursue and this was, in my opinion, one of many experiences that Kami was going to have in sports. Surely she’d get bored quickly and move on to the next thing, as is so often the case with children at that age.

I didn’t think it would become her passion to this day.

We never saw an innate talent for cheerleading in Kami—it just developed over time. After that first year with the Santa Inés team, the same coach, don Luis, seeing that Kamila had a lot of potential, took her to the All Star Panthers team to begin to refine many of the techniques and gymnastics that are used in cheerleading. By then, Kami was training four to five times a week.

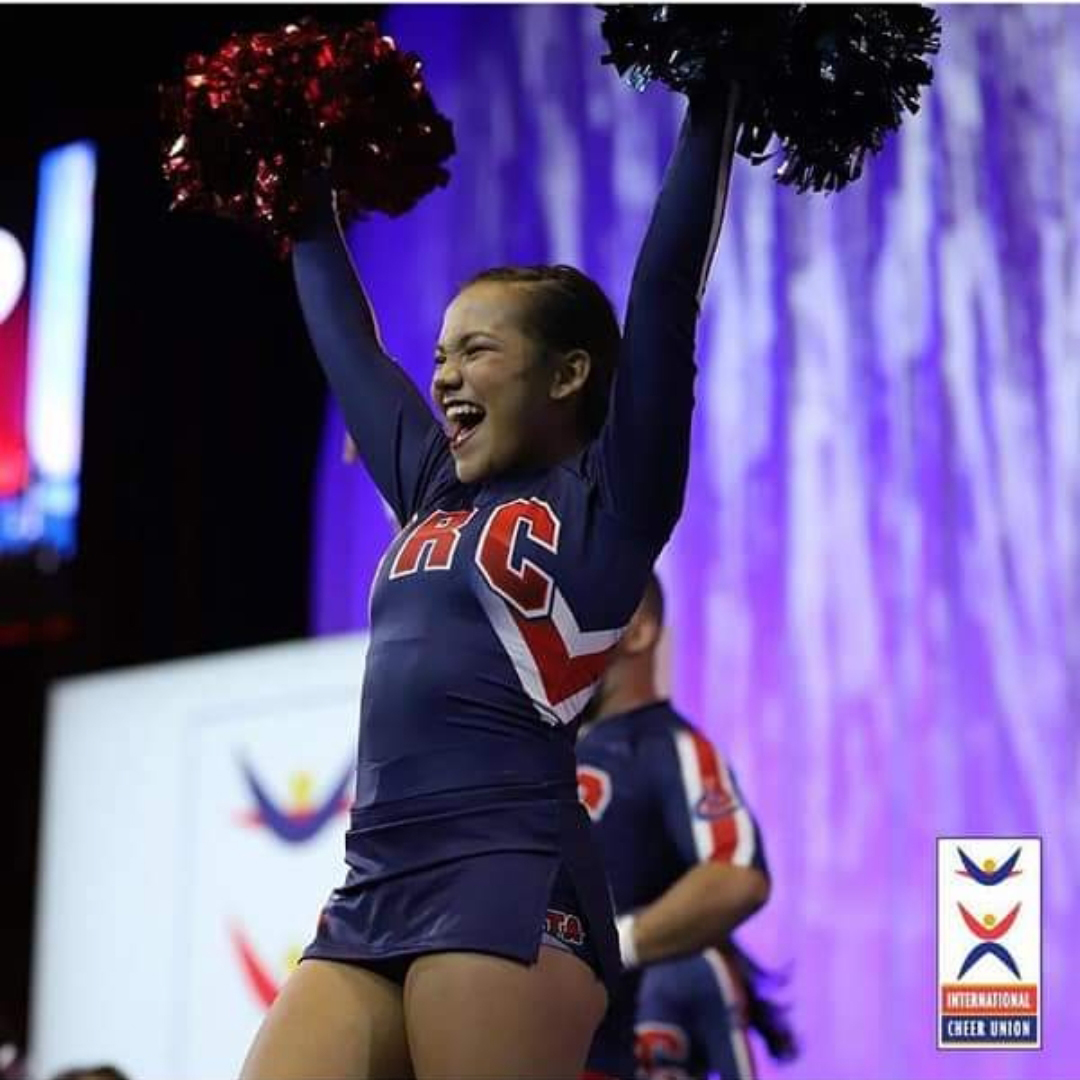

Then came the Intercollegiate Championships and the All Star Championships. As always, every sport begins with the idea of rewarding participation, instilling in athletes the concept that it doesn’t matter how they place. She placed third here, second there, and several times did not make the podium. I saw her cry many times with frustration in national tournaments because they did not get that longed-for first national championship and a year’s effort seemed to disappear, but Kami remained faithful to that love that cheerleading had awakened in her, and always went right back to training. Soon, that dream of being champions came true, and the school team produced a generation of impressive cheerleaders. They won four consecutive national championships and then, in high school, became Binational Champions, Grand Champions, and World Champions in 2019 in Orlando, Florida.

Thanks to these excellent results, in 2018 Kami was called up for the first time to be part of the Costa Rican National Cheerleading Team, which participated in the World Championship in Orlando, Florida, finishing fourth. In 2019 they participated again and made the podium, finishing in third place. That same year, they participated in the Pan American Cheer Games held in Costa Rica, winning a silver medal.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the year 2020 passed by without any sports. However, 2021 brought huge surprises for Kamila. Again, she was called up to the National Team, this time to be part of the All Girl Elite team. They started the year without being able to train, and all gyms closed. Little by little, reopening began, but they had to get used to training with a mask, not having a fixed location, and traveling long distances for training. Training was almost always possible only on Sundays. Even so, FECAD decided to participate in the Virtual Cheer Championship organized by the International Cheer Union (ICU).

With a lot of effort and dedication, the coaches and cheerleaders were able to establish a routine that allowed them to compete against world teams such as the Czech Republic, Japan, South Korea, Ecuador, Greece and Slovenia.

All teams had to record the presentations and send them to the ICU, but it’s not as easy as you are imagining: that you do it as often as you like, and send in the best result. No. The ICU sent judges to each country to ensure that teams recorded only one presentation. If there were mistakes or falls in that presentation, you couldn’t delete or send another version.

On Sunday, October 10th, the teams, coaching staff, federation, and parents met in one of the Amphitheatres of the National University in Heredia, where all the routines of all the participating countries would be broadcast, with the award ceremony immediately to follow.

One by one the teams were introduced: good routines, but nothing out of the ordinary. Then it was Japan’s turn, all with exact timing and a practically perfect routine. The Slovenes’ routine was formidable: these were the two teams to beat. Costa Rica put forth an impeccable routine, full of strength, energy and a lot of personality, with that Costa Rican flavor.

It was time for the awards. I was doubtful: I knew we were going to make the podium, but Japan and Slovenia had me doubting what position we were going to achieve. The presenters announce the third place: Slovenia. I was leaning towards the silver medal, as the routine in Japan was excellent.

The presenters announced the silver medal and called on Japan.

My heart began to race. I had trouble breathing. Because of the health regulations, there was no one by my side; I had no one to exchange looks with; we were all wearing masks, and I couldn’t see the expressions on people’s faces. I started to do a quick review in my mind of the routines— but no, the only two teams that could beat Costa Rica had already placed. That’s when the penny dropped. The presenters announced: “And the gold medal goes to… COSTA RICA!”

There was a roar. I went back to see the cheerleaders and they were all jumping, screaming and hugging. I was speechless. I was jumping up and down alone, like a crazy person. I thought, “I have to hug someone!” I remembered my friend Beatriz, the mother of one of Kami’s classmates who was my classmate from school. I went to find her, hugged her, and we jumped together. Then I went to find my daughter.

It was crazy what they experienced. We were all still wearing our masks, so it took me a bit to find her in the midst of so many people. When I managed to find her, her eyes were full of tears—those tears of happiness that one cannot describe, and her face was red from screaming. She spread out her arms to me with a happy cry. I hugged her and lifted her; I couldn’t say anything. The words did not come out. I was so excited that all I did was hold her and cry with her.

There was no room in my chest for this much pride: world champions!

The athlete’s sacrifice, and her family’s

Kamila trains with three teams: with her school twice a week, with the independent All Star team three times a week—on Saturdays, they train double—and with the National Team, who train on Sundays. She also goes to high school from Monday to Friday, from 7:20 am to 3:10 pm. She has to do homework, study for tests, and besides, she is one of the top students in her class… ah! And she goes out with her friends.

When you have a daughter who competes at that level, you have to understand and accept many things.

An example is the 24/7 availability of the athlete and her family. Kami’s mother and I take turns, since she has to be dropped off and picked up at the different places where she has to train. Sometimes it is the parents of teammates who take that on; other times, it’s up to us to transport multiple cheerleaders. When trainings are in Heredia, it’s easy, but many times it’s in San José, Coronado, training with the national team on Sundays in La Sabana, Escazú, or in Lindora at 3 pm (that takes all day!). There may be workouts at 8 am on a Saturday or Sunday, or workouts at 8 or 9 pm on weekdays.

We cannot count on Kamila for any family activity: birthdays, family trips, vacations, or anything else. She has to train, or she has championships or presentations. Then again, you have to accommodate schedules or interrupt those activities to go to drop off or pick up—or both.

But you learn to live with it. You learn that this is what she likes to do. To this day, after 10 years of accompanying my daughter on this journey, I have never heard her say “I don’t feel like training today.” That means I cannot fail her.

Going to cheerleading championships is pretty tiring, too. You have to sit for six to eight hours in a gym waiting for a routine that lasts two and a half minutes. The awards are always at the very end. Really, I only do this because she is my daughter.

Kami has a big advantage: her mother is a doctor. Any pain, discomfort or injuries she gets from training—which are many—can be checked and treated immediately by her mom so that the injury does not become more serious. To this day, thank God, she has not had an injury that prevents her from competing or missing significant periods of training.

Kami’s cheerleading has been worth every hour, minute, second and colón that we have invested. It has taught her to be disciplined, consistent, and strong both physically and mentally. It has taught her to avoid many situations that adolescents experience, but without neglecting her personal life.

I have seen her grow as a person, as an athlete, and as one of the leaders of the teams she is a part of. I’ve seen her help her teammates and encourage them. I have seen her cry, get angry, and suffer… but above all, I have seen her laugh, be happy, and succeed as an athlete and as a person.

My only advice for parents is to support their children in whatever sport or passion they have, be it learning to play an instrument, sing, dance, or paint. It is very important not to impose on them what we as parents like to do: “Because I like football, I am going to put him in a football school without even asking him if that is really what he wants.” Let’s break the stereotypes. If my daughter wants to play soccer, let her play soccer; and if my son wants to dance, let him dance.

Let’s not cut off their wings, their dreams, their passions. Let’s not see their abilities and skills in monetary terms. Let’s not encourage the idea that everything they do has to do with financial gain, nor tell them that practicing a given sport or passion is a waste of time because it will not generate money. On the contrary, let’s nurture those passions and energies, discovering those hidden talents that many children have but have not been able to discover.

And if they fail on that first try, don’t discourage them. Carry on to the next thing until they find the thing that fills them up and makes them happy—just as cheerleading has brought my daughter so much joy.