“Are you aware that you are depressed and ill?” the doctor asked me.

“Excuse me?”

He looked up from the page where he was noting answers to a series of questions designed to help him assess the presence or absence of depression. We were facing each other across his desk in a tiny consulting room, far enough back in the building that you could barely hear the ornery honks of rush-hour drivers outside. We’d been talking for more than half an hour. For the previous ten minutes or so on this evening in October 2021, we’d been exchanging questions and answers through our masks about my sleeping and eating habits, how often and easily I cried.

He repeated what he’d just said.

“Well, I’m not depressed or ill,” I said. “I’m just having trouble sleeping. Does that answer the question?”

There was a little silence while he tallied up my answers. I thought of those Cosmopolitan magazine quizzes where the final answer is so obvious throughout (you know, “Are You Really In Love?” “What’s Your Sex Position IQ?”). This time, I had no idea what the result would be, or whether it would actually reveal anything useful about the insomnia I’d been battling for months.

He made a little dot on the paper and turned it around so that I could see it. I was smack dab in the middle of the darkest section of the graph. Even before I deciphered the axes, I knew that when your doctor shows you a graph, the most brightly colored section is generally not a good place to be.

According to the instrument, I had severe depression and anxiety.

A while later, I was sent off into the crowded night with prescriptions—not only for medications, but also for concrete action steps that would start to alleviate the accumulated pandemic stress I’d been experiencing. He talked me through them slowly and unhurriedly, giving me plenty of time to ask questions.

As I walked outside again, I felt strangely light, almost euphoric. Traffic in the clogged street in front of me was flowing more freely than it had been when I went in. I took off my mask and stood on the doorstep. Just a few days after being named a Rosalynn Carter Fellow for Mental Health Journalism, I’d been diagnosed with a mental health condition for the first time in my life. For some reason, it made me feel much better.

I couldn’t help myself: before I even hopped into my car, I looked up the test he’d given me. I discovered it’s called the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, or HDRS. I scrolled through it, feeling the need to see, in English, that last question I’d found so interesting.

It says: “Lack of Insight? Acknowledges being depressed and ill; acknowledges illness but attributes cause to bad food, climate, overwork, virus, need for rest, etc.; denies being ill at all.”

I looked out at the cars easing by on Avenida Dos. The relatively narrow street is actually part of the Inter-American Highway; if I’d turned left, I could have taken it to the Nicaraguan border, and right, all the way to Panama. For a moment, I felt overwhelmed by the sheer number of Costa Ricans and the amount of stress this pandemic has foisted on everyone.

I realized that, right there in the little parking lot, I was standing on the very peak of privilege. My background and economic circumstances had not only protected me from so many of the worst mental health effects of the pandemic, but also allowed me to call up a doctor and make an appointment for that very day, and pay him 30,000 colones (just under $50, a standard fee for a private appointment outside of the universal public system) without much thought. I’d been able to talk to him for as long as I liked. If I needed to see him again tomorrow, the next day, three times a week, that was all within my grasp.

I had already been sufficiently passionate about mental health in Costa Rica to set my sights on creating a permanent section devoted to this topic at El Colectivo 506. Still, at that moment, I felt as if a lightning flash had illuminated the San José sky.

If I had reached this point—so anxious that I couldn’t sleep, and completely unable to see what was going on inside my own brain and body—how was the rest of the population surviving?

Bracing for impact

Short answer: I still have no idea. After wading through data on Costa Rica’s current mental health outlook and speaking with some of the country’s foremost advocates, I am even more astonished by the loads borne by the five million people around me.

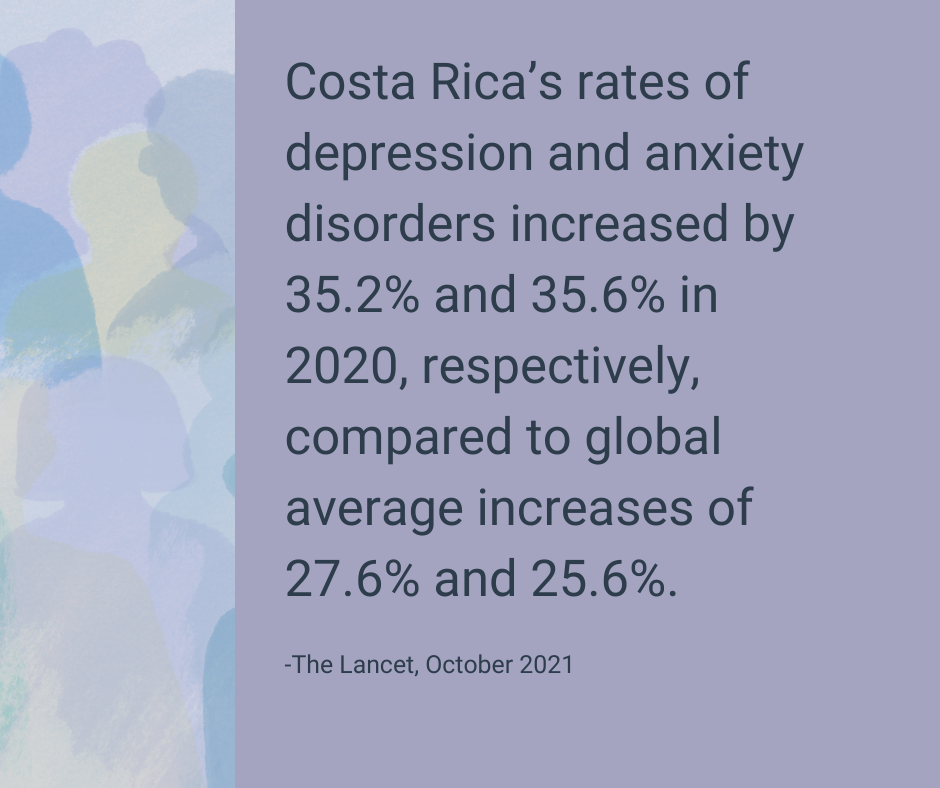

When it comes to mental health, Costa Ricans aren’t just keeping pace with the global overwhelm caused by the pandemic: its soaring reports of disorders have increased significantly more quickly than the global average. A regional study published by The Lancet in October 2021 showed that Costa Rica’s rates of depression and anxiety disorders had spiked by 35.2% and 35.6% in 2020, respectively, over the numbers from 2019, compared to a global average increase of 27.6% and 25.6%. Two public universities, the State Distance University (UNED) and National University (UNA), found even higher figures—for example, a 50% jump in depressive symptoms from March to October 2020.

How does this manifest for Costa Ricans? Respondents to the UNA-UNED study said that job loss, an overload of caregiving tasks, and economic and food insecurity were their leading stressors, affecting them in various ways. Those effects included physical impact such as fatigue, muscle pain, headache, accelerated heartbeat or breathing, and stomach pain; behavioral impact such as increased consumption of caffeine, nicotine, alcohol or other substances; and cognitive impact such as difficulty relaxing and making decisions. (That night in the parking lot, I knew I wasn’t alone, but I didn’t understand how crowded my doctor’s office really should have been. A whopping 91.3% of Costa Ricans reported difficulty sleeping.)

Unsurprisingly, the UNA-UNED survey as well as a national study by the University of Costa Rica’s Institute of Psychological Research showed that women and youth, low-income families and coastal regions are bearing the brunt of the mental health impact. And in a country where most community health teams, or EBAIS, lack a mental health professional, and where inpatient mental health treatment generally requires a transfer to the country’s capital, the road to treatment for a rural citizen is a long one.

Costa Rica is rightly renowned as a wellness destination, and hovers atop international happiness surveys on a regular basis. Without a doubt, it is a country whose natural landscapes and people enhance the happiness and well-being of millions of tourists each year. And it is a middle-income country that, despite its limited resources, has created a universal health system that outpaces some developed nations.

It is also a country where mental health care has been long neglected. Despite its historic commitment to public health, Costa Rica didn’t have a national policy on public health until 2012. It has implemented only a small percentage of the resources assigned to the National Mental Health Secretariat created to oversee the implementation of that policy; has not replaced the Secretariat’s director, who retired in 2020; and, as of the time of this writing in June 2022, had not even evaluated the 2012-2021 policy, let alone created a new one.

In other words, Costa Rica appears to have gone off the rails of its mental health implementation timeline at the height of what is arguably the worst global mental health crisis in history.

How did we get here after such a promising reboot to the country’s approach to mental health, just 10 years ago?

A host of good intentions

At least to my inexpert eye, Costa Rica’s first-ever National Policy on Mental Health—a document meant to govern the country’s mental health efforts from 2012-2021—is thorough and thoughtful. It calls for an ambitious and dizzyingly inter-institutional effort to decentralize mental health care, reduce the emphasis on institutionalization and strengthen community networks to improve mental health in a holistic way. If fully implemented, the 137-page document would have led to improvements in Costa Ricans’ access to green spaces, housing facilities, bike paths, high-quality drinking water, and spaces free from noise pollution, not to mention mental health care services.

However, according to all those interviewed, the plan is far from full implementation. Of course, interviews conducted in late 2021 focus on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the plan’s implementation: “During the crisis, everything was on standby,” says Marta Vindas, head of psychology for Costa Rica’s public health care provider, the Social Security System (Caja).

But the policy’s problems predated the pandemic. Looking a few years further back reveals that implementation of the plan was deeply flawed before anyone had heard of COVID-19. In particular, an audit performed by the Comptroller General’s Office in 2018 reads like a textbook analysis of an underperforming government initiative.

Those textbook chapters? Lack of regulation, lack of staffing, lack of continuity between presidential administrations, and a resulting under-execution of budgetary resources.

The Secretariat charged with implementing the policy was created by a law that allows three months for the accompanying regulations to be finalized, but that process took 4.5 years, hamstringing the Secretariat in the meantime. The Secretariat hasn’t received the personnel it requested from the Health Ministry. Changes in presidential leadership have resulted in what the report calls “modifications of previously defined priorities.”

In terms of budget, even though the Secretariat didn’t even receive all the resources it was assigned by Law 8718—it was 89 million colones short, approximately $130,000, as of the time of the Comptroller’s report on Aug. 31, 2018—it had still spent only 19.50% of its assigned resources (128.9 million of 433.8 million colones, or approximately $197,000 of of $665,000).

The policy’s Action Plan “does not include, for example, a budget to implement its actions, concrete goals, baselines or indicators that facilitate monitoring,” the report states. “The initial evaluation, which should have been carried out at the end of the 2013-2015 triennial, has not been carried out.”

Fast forward to 2022 and a country reeling from the impact of a global pandemic, and you guessed it—massive implementation gaps remain. Secretariat head Francisco Gólcher Valverde retired from his post in December 2020 and has not been replaced to date; scheduled evaluations have not yet been completed; and, of course, the 2012-2021 policy framework has not yet given way to a new policy for 2022 on.

So what’s going on, and what can we expect?

A leadership gap

One result of all these delays, according to the Health Ministry Press Office, is that interviews on this topic can’t be granted—at least until the scheduled final evaluation of the 2012-2021 plan is completed. While the first triennial evaluation was postponed, as described in the Comptroller’s report, the press office says that a consulting firm was hired to do a “revision” of the plan in 2017-18 and is now working on the final evaluation of the 2012-2021 period, which will be completed this month. So, watch this space.

What about a new head for the secretariat? While I haven’t been able to confirm this, it’s probable that the much-delayed process was delayed still further by the impending arrival of a new president, Rodrigo Chaves, and his pick for Health Minister. Now that Chaves has been sworn in, the Health Ministry’s press department responded to our queries this week by explaining that “the person who will be in charge is in the process of being named by Human Resources.”

What about the fact that the country has no official Policy to date, at a time when mental health needs are arguably more acute than ever? When can a new Policy be expected? “Work is being done on a new policy,” the press office states, arguing that the impact of this delay of the actual progress towards the policy’s goals has been minimal. “The Secretariat… has been coordinated from the Office of the Minister since the retirement of its head. At this time, it’s under the responsibility of Dr. Alexei Carrillo Villegas, viceminister of Health.”

When the old Policy expired, then-Health Minister Daniel Salas “told the entities involved that until the evaluation is complete and a new Mental Health Policy is created, the 2012-2021 Policy and its action plan remain in place until 2023.”

In addition to filling these voids, more fundamental changes are needed, according to Dr. Ángelo Argüello Castro, president of Costa Rica’s College of Psychologists. He says that while the organization initially applauded the policy, “today, in contrast, we’ve been obliged to point out that state authorities should have gotten more involved when it comes to putting their boots on and going out into the battlefield. Helping each person in each institution to understand their roles within the national mental health policy. Not just giving them an assignment, giving them instructions, and that’s it.”

He says that, for example, the policy relies heavily on implementation by local authorities, but not enough energy was invested in ensuring their buy-in. Marta Vindas, from the Caja, echoes the idea that building up support is important: “The topic of mental health is still a confusing topic in this country. Not everyone focuses on it, so you have to create the path, which makes everything slower.”

Karolina Ulloa, one of the three Health Ministry officials now working at the Secretariat for Mental Health, described in December 2021 a short-staffed operation that’s doing its best.

“There are very few of us… just three psychology professionals,” she says, explaining that the three have divided up the work by thematic area as well as by region. Each one coordinates the ministry’s mental health initiatives in two to four regions; these range from regional diagnostics to mental health trainings for primary care staff.

“It’s a titanic task, a marathon, I tell my colleagues,” Karolina admits. “But not impossible.”

Never waste a good crisis

“Lack of Insight? Acknowledges being depressed and ill; acknowledges illness but attributes cause to bad food, climate, overwork, virus, need for rest, etc.; denies being ill at all.”

If insight means acknowledgment, then the COVID-19 pandemic has helped Costa Rica cross the finish line. Costa Rica’s mental health services are insufficient, with inequalities and gaps that run much deeper than one virus, and much further back than 2020. Across the board, those at the forefront of public health leadership, academia, private practice and advocacy, admit that there is a problem.

There is also great potential. Despite all the shortcomings and setbacks, Costa Rica still enjoys a particular and unique position in the developing world thanks to its public health infrastructure—which has consistently demonstrated its capacity through its muscular and efficient response to COVID-19. Even if most components of its ambitious mental health policy remain on the page, Costa Rica is positioned to generate answers for other countries trying to provide better mental health care with fewer resources.

In 2022, that describes almost every country on Earth.

So at this critical moment, with authorities in San José still resolving central government issues, how can the gap in support for Costa Ricans with mental health challenges be most effectively addressed?

Another Lancet study from 2021 argues that more diverse resources, outside of clinical settings, need to be enlisted. “Religious centres, community ties, family support structures, traditional healers, village leaders, and youth groups are all contextually varying resources that are essential to engage with to overcome mental and physical health threats,” wrote Lola Kola and a host of co-authors. They say that focusing on communities’ strengths in mental health responses, rather than deficits, can help “avoid the displacement of effective local strategies.”

That’s why today, with this story, El Colectivo 506 is launching a quest for another kind of insight: the insight we can glean from Costa Ricans who are making a difference on this issue at the local level. This month, through the support of the Rosalynn Carter Fellowships for Mental Health Journalism, we will publish our solutions journalism stories about community efforts to improve mental health in Costa Rica. From there, we will continue working with local media organizations and journalists to develop and publish projects in this space, our Mental Health Route: a permanent channel dedicated to this topic.

You can join us as a community member, by telling us about mental health solutions in Costa Rica at sala506.com/saludmental; as a reader, by signing up for our free Weekend Reader and considering an Annual Membership to increase our funding for rural journalist stipends; and as an organization, by contacting us at [email protected] or 506.8506.1506 for more information on becoming part of our Mental Health Route.

Why now? Because there’s only one good thing about the fact that more people than ever before are suffering simultaneous mental health challenges: awareness is also at an all-time high.

Ángelo Arguello, of the College of Psychologists, says Costa Rica can’t afford to miss this moment.

“For mental health specialists, the pandemic, well-managed, is a golden opportunity,” he says. “The current policy created a National Council on Mental Health that gives support to the Secretariat. That’s fine, but it stays up there in heaven, in the city, on Mount Olympus… we have to grab that idea of a mental health council and bring it down [to the community level].”

We’re proud to be working with artist Nela Snow for our new Mental Health Channel. Learn more about her work here.