The reintroduction of extinct species in protected areas across the country has been highlighted by international organizations—but this ecological restoration strategy faces controversies and challenges that test the continuity and dialogue among science, the state, and communities. Journalist Cecilia Fernández Castañón tells the story in this piece produced with the support of Earth Journalism Network through the Latin American Solutions Journalism Fund, an initiative of El Colectivo 506. It was published in collaboration between Ambientenea, eldiario.ar and El Colectivo 506 in November 2025, and was adapted and translated here by El Colectivo 506 for co-publication. ChatGPT was used for translation support.

It’s estimated that more than 40 jaguars (Panthera onca) are roaming freely in national parks in northern Argentina after being reintroduced into natural environments where the species was once considered extinct. The project that enabled the recovery of this feline population—vital to the region’s ecosystems as the top predator—is recognized worldwide as a successful case of rewilding, a technique that seeks to restore natural processes in environments degraded by human intervention.

The reintroduction of the jaguar adds to other initiatives involving various species that have taken place for almost two decades in different parts of Argentina. These efforts aim not only to conserve natural environments, but also to restore what has been lost. Combining scientific knowledge with public commitment and community participation, these projects seek to offer a solution to the global biodiversity crisis.

Ecosystem restoration not only allows for the recovery of ecological functions but also creates economic benefits based on nature tourism. However, this ambitious conservation model faces controversies and challenges that call for stronger dialogue among participants. The continuity of monitoring projects is also under threat due to defunding of the national scientific system.

The ecosystem crisis

Like other South American countries, Argentina faces an alarming loss of biodiversity caused both by the global climate crisis and by deforestation of native forests. Large-scale agriculture and livestock farming have deepened the process of defaunation, the local extinction and decline of animal populations. This has drastically altered ecosystems such as the Gran Chaco, the Iberá Wetlands, and the Patagonian Steppe.

This phenomenon affects not only ecosystems but also local communities, eroding natural resources and cultural heritage across the country. The urgency of the crisis lies in the collapse of food chains among animals, as well as the loss of key species whose disappearance may be irreversible.

The case of the jaguar is emblematic: it is the largest feline in the Americas, declared a National Natural Monument, and is listed as Critically Endangered (Pelígro Crítico, or PC) in Argentina. The species’ total population is estimated at just 200 to 300 individuals, surviving in only three fragmented areas after losing more than 95 percent of its historical range. The situation is especially critical in Gran Chaco, where fewer than 20 individuals remain and only 3 percent of the territory retains optimal conditions.

Restoration as a response

Faced with the accelerated degradation of biodiversity, rewilding (or reasilvestramiento) has gained prominence as a conservation strategy that seeks to reestablish lost species diversity, restore natural processes, and rebuild ecosystem resilience on a large scale. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) defines this practice as the process of rebuilding a natural ecosystem after major human disturbance, with the goal of restoring natural processes and the food web at all levels.

To provide a common framework and guide this complex and sometimes controversial practice worldwide, the IUCN developed a guide for rewilding, presented in early October 2025. The document establishes a global standard to ensure that restoration efforts are strategic, evidence-based, and adaptable to diverse contexts. It resulted from a process that began in 2017 and brought together more than 100 experts from 63 organizations, including Indigenous representatives, academics, and NGOs.

In the new guide, the IUCN outlines five essential principles for every rewilding project, emphasizing that ecological restoration should be functional and driven by nature itself—not human control. It must also be an ambitious, large-scale strategy planned at the landscape level and based on collaboration. Scientifically, the guide requires projects to be grounded in evidence with continuous monitoring and for managers to embrace the dynamism and systemic complexity of ecosystems. It also stresses the importance of local participation and cultural rootedness.

Argentina has been developing rewilding projects for nearly two decades, led by the Rewilding Argentina Foundation, an NGO formally established in 2010 but rooted in conservation projects begun in 2005 by Douglas and Kristine Tompkins. The U.S. philanthropists acquired land in different parts of the country and donated it to the state with the commitment that it be turned into national parks.

The regeneration of wildlife

Argentina’s rewilding experience is featured on page 45 of the IUCN guidelines, in a section titled “Restoration of Ecological Functionality in the Iberá Wetlands”—an area degraded by intensive agriculture, livestock, and forestry. The project’s main goal, according to the document, was to reestablish lost ecological processes through the reintroduction of key species to rebuild functional food webs and create a self-sustaining, biodiverse ecosystem.

The model applied, called “full nature,” not only revived ecosystem health on a large scale but also generated sustainable livelihoods for local communities through ecotourism, demonstrating that functional restoration is achievable. It serves as a replicable model integrating science, community commitment, and adaptive management.

“The results we’ve achieved are very satisfying because we’ve managed to create self-sustaining populations in the protected areas where we work. We started with giant anteaters in the Iberá Wetlands, and now we no longer do any active management with that species—only annual monitoring. The same happened with the collared peccary and the pampas deer, and the same will happen with the jaguar, which has already begun reproducing on its own,” said Sebastián Di Martino, Director of Conservation at Rewilding Argentina, in an interview with ambientenea.

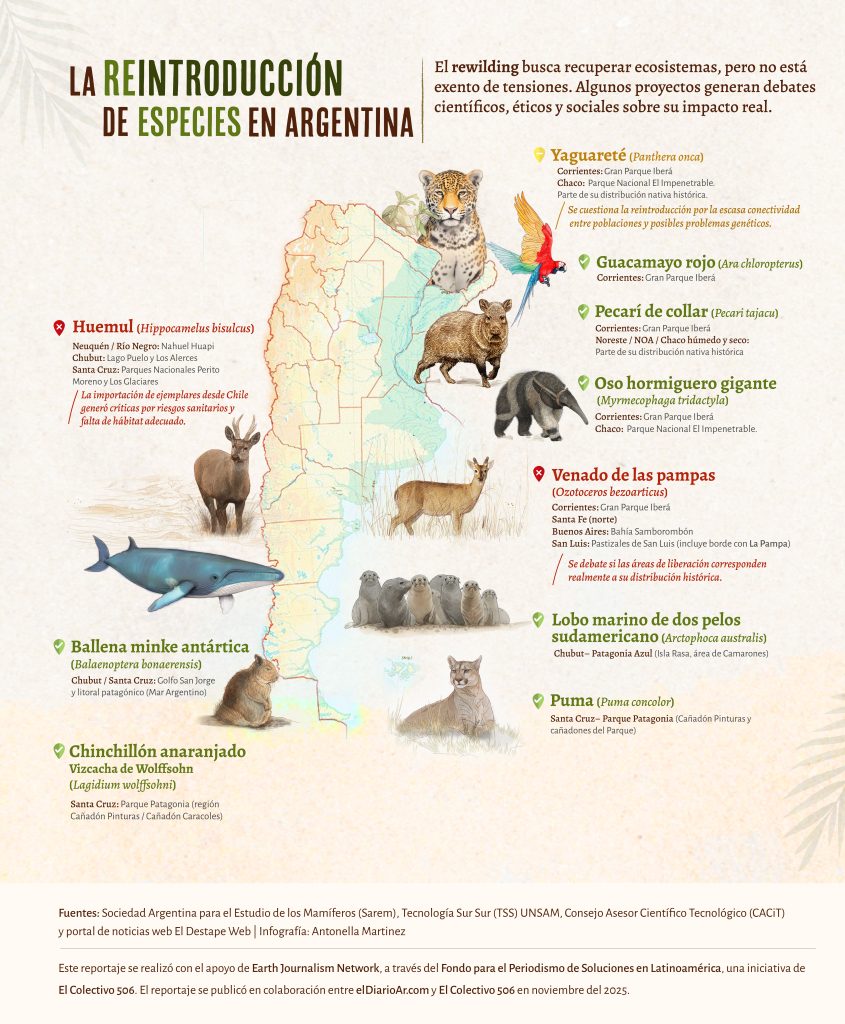

In addition to the restoration of the jaguar and the giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla), there are also reintroduction projects for pampas deer (Ozotoceros bezoarticus), collared peccary (Pecari tajacu), and red macaw (Ara chloropterus) in the degraded ecosystems of Iberá and El Impenetrable. The organization also works in Patagonia monitoring key mammals such as the puma (Puma concolor), huemul (Hippocamelus bisulcus), and Wolffsohn’s viscacha (Lagidium wolffsohni), as well as in its Marine Program with species such as the South American fur seal (Arctophoca australis) and the minke whale (Balaenoptera bonaerensis).

Because these projects take place in protected areas, collaboration with state agencies such as the National Parks Administration is essential.

“One of the objectives linked to these projects has to do with local community development, because rewilding generally increases the tourism appeal of these protected areas, leading to more visitors and higher demand for services offered by residents—guided tours, food, and other ecotourism activities,” said Anabel Fossi, National Director of Conservation, in an interview with ambientenea.

A positive example of conservation and tourism’s impact on local communities is the story of Mabel Figueroa, a weaver from Pozo de la Gringa. Mabel, who lives near the entrance to El Impenetrable National Park in Chaco, transformed her ancestral practice of loom weaving and natural dyeing—using plants from the Chaco forest such as mistol, molle, carandá, and palo santo—into a business that now supports her family’s income.

Before, she wove only for family use. But for the past two years she has been weaving “especially for tourists,” selling items such as bed runners, table runners, and ponchos. She says this transition was possible thanks to the park’s support, which allows her to sell her crafts directly to visitors, either from her home or at the Workshop School in La Armonía.

Controversies over impact

Argentina’s rewilding strategy faced controversy in recent years due to disputes among the scientific community, state agencies, and the NGO leading the projects. The debates centered on methodologies, species selection criteria, and the lack of published technical reports and results.

In a 2023 scientific journal article, a group of more than 100 authors—including researchers from the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET) and members of the Argentine Society for the Study of Mammals (SAREM)—questioned the rationale behind reintroducing species into habitats with limited evidence or ongoing threats, such as the marsh deer in El Impenetrable and the huemul in Patagonia. They cited sanitary and genetic risks. The debate, initially meant to be academic, escalated when the Rewilding Argentina Foundation responded by sending legal letters to the article’s authors.

The scientific community and CONICET interpreted this legal action as an attempt to intimidate academic dialogue. Although the case faded without legal consequences, it effectively halted a scientific debate crucial to improving rewilding practices in the country.

“In that article, we aimed to highlight ongoing informal discussions about the need to consider various aspects that justify rewilding projects. It’s not enough to know whether a species lived in an area 50 or 100 years ago, because those areas have undergone changes that must be addressed—human activities, environmental shifts, and the cultural values of the communities living there. It’s not sufficient to say a species once lived in a place and therefore must return. That’s the debate we wanted to open in the scientific field, but unfortunately, it turned into a legal conflict that was very uncomfortable,” said María de las Mercedes Guerisoli, a biologist and lead author of the 2023 article published in Mastozoología Neotropical, in an interview with ambientenea.

Beyond the disputes with scientists, tensions also arose with the National Parks Administration (APN). Ana Mattarollo, former Coordinator of Environmental Planning and Management at the agency, said state structures faced a major challenge when they began working with philanthropic organizations used to different management mechanisms.

“When the foundation led by the Tompkins began donating land with the condition that it become national parks, we had to review zoning and management categories. That made us realize we needed to update governance approaches and prepare for greater flexibility. It was challenging because, in many cases, the state lacks tools to respond to organizations that are faster and less bureaucratic,” said Mattarollo, who worked for 17 years in the national administration, in an interview with ambientenea.

These conflicts revealed cultural, ideological, and technical differences about how conservation should be done in Argentina—through agile, philanthropic intervention, or through traditional, transparent state processes.

While scientific research is key to resolving controversies surrounding rewilding and ensuring adaptive management of new protected areas, the continuity of monitoring projects is threatened by cuts to Argentina’s scientific system. Funding reductions, limited research grants, and salary cuts are all taking a toll.

Mario Di Bitetti, a CONICET researcher specializing in large mammal ecology and conservation and involved in several monitoring projects in Iberá, warned in an interview with ambientenea about difficulties in sustaining long-term studies. “National funding has been cut. There are no funds for any type of project. We’re surviving on international grants that will last us one or two more years,” he said. But the bigger problem is that salaries in the national scientific system are very low, and access to scholarships or research positions is extremely limited. It’s very hard for young people to see a future in a scientific career that allows these projects to continue—projects that are essential to our ecosystems’ future.”

A global lesson

Argentina’s rewilding experience is beginning to shape a paradigm shift in conservation, showing that large-scale restoration of ecological functionality in degraded landscapes, such as Iberá, can be replicated elsewhere, as the IUCN’s recent publication notes. However, it also highlights the need to address the social and political dimensions of rewilding through consensus and to avoid unnecessary controversies within the scientific community.

To resolve differences, Mario said it’s essential to create more spaces for dialogue.

“Scientists from different specialties, with different views on conservation—along with state representatives and foundation leaders—need to participate in more forums for dialogue,” he said. “Differences will keep arising, but criticism should focus on ideas, not institutions or people. Scientific research is the only path to resolving controversies and advancing adaptive management. But that takes time.”

Similarly, Ana believes that state agencies must continue strengthening public participation in decision-making about protected areas.

“Public participation and democratization of decision-making spaces are crucial for transparency in consolidating new national parks, especially those that include Indigenous communities, such as some of the areas where reintroduction projects are underway,” said the former official, now working at the Ministry of Agrarian Development in Buenos Aires Province.

In that context, the Fourth National Meeting on Ecological Restoration of Argentina (ENREA), to be held in Corrientes from Nov. 12-15, gains particular relevance. The event will bring together experts to promote transdisciplinary work and share experiences, providing a key opportunity to strengthen dialogue and ensure that rewilding aligns with ecological, social, and political frameworks that advance biodiversity conservation.

With the successful recovery of jaguar populations in Iberá, Argentina’s rewilding experience is consolidating as a global reference model, proving that ecological restoration is possible. But the true challenge of conservation lies not only in returning wildlife to its habitat, but in building lasting consensus that combines the strength of the national scientific system with opportunities created by foreign philanthropic foundations.

Only through such dialogue—one that also integrates local communities’ needs and transparency—can the return of the jaguar and other species become not only ecological success stories, but also the reflection of a society seeking to restore life at every level.