In northern Peru, the dry forest is dying. Over the past 23 years, more than 440,000 hectares of this vital ecosystem—one that regulates the climate and supplies water to rural communities—have been lost. Amid this environmental crisis, women such as Gladys Huamán, in Piura, are leading reforestation and conservation initiatives using native species including the carob tree. Despite illegal logging, pests, and the lack of government oversight, community members refuse to give up: they are restoring the forest, rebuilding their economy, and reaffirming their bond with the land.

This story was created with a Reporting Grant on Nature-Based Responses to Biodiversity Loss in Latin America, provided by the Latin American Solutions Journalism Fund, an initiative of El Colectivo 506. The fund’s support for this story was made possible by a donation from the Earth Journalism Network and its Biodiversity Media Initiative. The article was originally published by Norte Sostenible in November 2025. It was adapted and translated here by El Colectivo 506 for co-publication.

The sun is just beginning to rise, and the air smells of dry leaves. Gladys Huamán, 27, begins her day walking calmly among the trees, her gaze steady. Her sun-browned skin reveals the years spent under this burning sky, caring for the forest that is her home.

With every step, the crunch beneath her shoes reminds her of the same sound she heard as a child when her father taught her the secrets of this forest. It’s a sound that is less and less common each year—because of illegal loggers, and because the state, here in Serrán, in the province of Morropón, Piura, is just a distant word.

Years ago, Gladys would hear her father speak of the forest as if it were alive. He was one of the first community members to fight to protect this natural space, back when no one was talking about conservation. When she was 11, and a white-winged guan —an endangered bird once thought extinct—reappeared in her community, something awoke inside her. From then on, she knew her life would be tied to the dry forest, an emblematic ecosystem of northern Peru. Today, the promise she made to her ancestors remains strong: to care for the carob trees and other species that still survive the heat and the illegal logging.

Her struggle is a race against time. The dry forest—home to the carob, sapote, and faique trees—is disappearing. In the past 23 years, northern Peru has lost more than 440,000 hectares of this ecosystem, which spans the regions of Piura, Lambayeque, Tumbes, and La Libertad, according to MapBiomas Perú.

Deforestation advances under the force of illegal logging, agricultural expansion, pests, and a lack of oversight by authorities. In northern Peru, the loss of the dry forest is more than just a statistic: it represents the disappearance of an entire way of life. Each felled tree means less food for livestock, fewer carob pods for residents, less shade for the desert, and fewer ecosystem services. As a result, the heat intensifies, rainfall decreases, and rural communities are left without resources or water.

In this story, Norte Sostenible reveals the devastation suffered by the dry forest of northern Peru—and how rural communities and various organizations are launching restoration and reforestation initiatives to reverse this loss, restore the forest’s value, and show that there is still hope.

An ecosystem in agony

Northern Peru, home to the dry forest, is facing one of the worst environmental crises in its history. In the last 23 years, it has lost 440,021 hectares of this ecosystem [approximately 1,087,315 acres]: 280,974 in Piura, 136,089 in Lambayeque, 15,206 in Tumbes, and 7,752 in La Libertad.

Analysis of historical satellite maps from MapBiomas Perú, compiled by Norte Sostenible, confirms a sustained loss. Between 2010 and 2024 alone, 252,179 hectares were lost—an average of 18,000 hectares per year. However, according to engineer Abraham Díaz, former head of the Norbosque program at the Piura Regional Government, the annual deforestation rate was estimated at 20,800 hectares as of 2014.

“In regions like Piura, Lambayeque, and Tumbes, where extreme heat is increasingly common, losing dry forest means losing our natural ability to regulate climate and retain water”

(Jorge Palacios, president of the Algarrobo Technical Roundtable)

The causes of deforestation identified by the Ministry of the Environment (Minam) are numerous, but the most prominent are land-use changes for agriculture and the illegal logging of trees such as the carob, a species vital to the dry forest ecosystem.

Roberto Fernández, Forest and Wildlife Technical Administrator at SERFOR—the agency responsible for combating illegal logging—reveals that in Piura, which contains 65% of Peru’s dry forest, there are only two control posts to monitor 36 identified routes used for illegal carob timber transport.

The main challenge in enforcement, Roberto warns, lies in the traffickers’ methods. Carob wood is burned into charcoal within the forest itself, making it difficult to trace and easy to transport illegally.

The impact on communities

To the dry forest’s long-standing problems, new threats have been added: pests that destroy the carob trees, weak public policies for ecosystem restoration, and a lack of environmental monitoring. In many areas, recovery depends almost entirely on community organization and on the commitment of citizens such as Gladys Huamán.

This loss has triggered a severe degradation process that has accelerated to the point of becoming an environmental crisis. In Piura, Jorge Palacios warns that degradation levels already exceed 60%, and in Lambayeque they reach up to 70%, affecting family incomes and food security.

In communities such as Locuto and Ignacio Távara in Piura, the effects are already visible. The production of honey and carob pods—the foundation of the local economy—has fallen by up to 70%. The health crisis affecting the dry forests is due to a pest caused by larvae that settle on the leaves, stripping the tree from bottom to top and leaving it vulnerable to other vectors that eventually kill it, Jorge explains.

This impact on the rural economy has led many communities to get directly involved in restoring the dry forest, with one goal: to bring life back to the ecosystem that has sustained and inspired them for generations.

Initiatives to save the dry forest

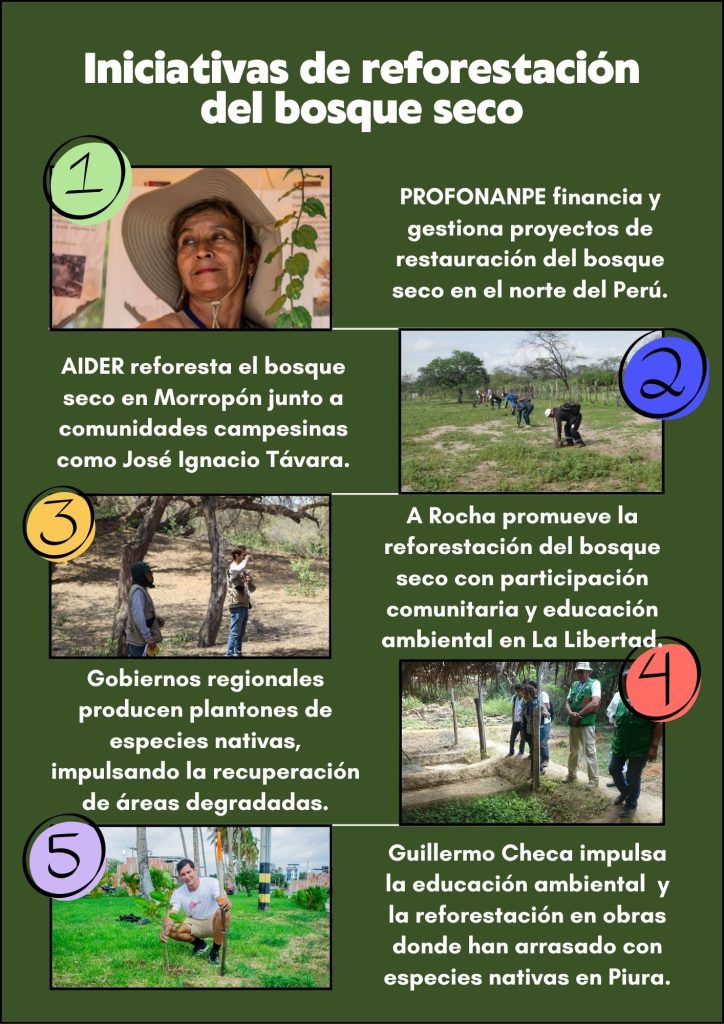

In the face of accelerating deforestation and biodiversity loss in the north, communities and organizations have launched a race against time to restore the forest. The proposal, first developed in the 2000s by the Center for Research and Promotion of the Peasantry (CIPCA) and the University of Piura (UDEP), involves reforesting with native species. It’s not just about planting trees—it’s about rebuilding life in the desert, in harmony with its natural identity.

The process requires patience. Seeds are collected from mother trees, germinated in nurseries, and, once strong enough, transplanted into degraded areas. There, community members play a key role: watering, cleaning, and protecting the seedlings under a relentless sun, while illegal loggers wait for any moment of inattention.

In Piura, the Chira Agricultural Agency nursery produced more than 3,600 seedlings this year, and the Poechos nursery, run by the Chira-Piura Project, aims to produce 200,000 annually. The National Water Authority is also reforesting 744 hectares of forest in the Pusmalca micro-basin. Although this area lies in the highlands of Piura, its hydrological impact contributes to recharging the lower valley, where the dry forest ecosystem is found.

Historical records show that the rains brought by the 2017 El Niño phenomenon enabled the reforestation of nearly 2,000 hectares of dry forest in the districts of La Arena, Catacaos, and Tambogrande, using soil moisture to promote the natural germination of carob trees.

But the most profound change is not in the numbers. It’s in the people. And Gladys knows this well. When she joined the Profonanpe Dry Forest Project, mistrust ran deep.

“At first it was hard,” Gladys recalls. “Many didn’t want to hear about reforestation. They thought we were going to fence off the hills and that their livestock would be left without pasture.”

Everything changed when training sessions arrived along with job opportunities.

“During reforestation and cleanup campaigns, more people decided to join in. Now they know the forest can provide work and a livelihood if it’s managed well,” she says.

Gladys’s story is not unique. She’s part of a growing network of reforestation initiatives stretching from Tumbes to La Libertad, led by communities, associations, and local and regional governments. In Locuto, for example, Leonel Temoche leads the “Adopt a Tree” program; in Mangamanguía, Reina Gómez works with groups of women conservationists who combine beekeeping with reforestation.

“It wasn’t easy to convince everyone. They thought we wanted to impose rules or close the hills. But over time, they understood that conserving also means producing.”

Reina Gómez presidenta de la Asociación de Mujeres Conservacionistas del Bosque Seco del caserío Mangamanguilla

Today, these communities have become regional examples. Community nurseries have created up to 50 temporary jobs per campaign, and eco-entrepreneurship fairs showcase products derived from the dry forest: honey, algarrobina syrup, soaps, and teas.

These experiences have even expanded to more arid zones, such as the Sechura Desert, where a private company has reforested 350 hectares of dry forest in previously barren areas that are now green spaces.

PROJECT. A private company is also carrying out a reforestation project in the Sechura desert.

The power of technology and community

Although northern Peru is beginning to chart a conservation path, some institutions believe strategies must be carried out more aggressively. To that end, they are testing a new strategy: aerial reforestation using a mix of native species such as charán and palo verde.

With high-capacity drones, multispectral sensors, and a science-based approach, Piura aims to replicate natural ecosystem processes and reverse the annual loss of thousands of hectares.

“We want to imitate nature—to plant using rainwater. That’s why we’ll use drones capable of carrying up to 50 kilos of seeds,” explains engineer Mario Moscol, Natural Resources Manager for the Piura Regional Government.

Unlike conventional projects that manage to reforest just 100 to 200 hectares, the aerial reforestation plan aims to scale up to “thousands of hectares in a matter of days.” Still, Mario insists that technology alone isn’t enough: “Drones can plant, but only communities can make the forest grow. We want every community to take responsibility for the trees that are planted,” he says.

However, these technological projects must be complemented by coherent, sustainable urban policies. While reforestation efforts expand in rural areas, the city of Piura—where summer temperatures reach 38°C—is cutting down its urban trees to make way for cement infrastructure.

On Don Bosco Avenue, more than 500 trees have been felled, and on Grau Avenue, 30 more are slated for removal. The same pattern repeats in multiple urban projects. Although Mario notes that an ecological compensation policy will be introduced for any public works that affect the urban dry forest, experts warn that the short-term impacts are already evident: more heat islands, less shade, and fewer ecosystem services.

Adding to the problem, there is still no unified long-term monitoring system to measure the effects of reforestation on carbon capture, desertification reduction, or biodiversity recovery. The available data come from scattered regional government reports, pilot projects, and NGOs such as AIDER, which since 2015 has promoted carob tree planting in northern communities.

A first step, recommends engineer Gastón Cruz, professor at the University of Piura, would be for authorities to conduct a census of carob stumps—a detailed registry of tree remnants in both urban and rural areas. This census would identify where trees have been felled, how many, and whether natural regeneration is possible or urgent reforestation is required.

The lack of a consolidated database prevents accurate evaluation of seedling survival rates, water balance, and long-term economic impact. Yet community perception and visible field evidence confirm that the dry forest is being reborn—slowly, but with stronger roots.

The challenges ahead in saving the dry forest

Despite the enthusiasm, the challenges in preserving the dry forest remain. José Remigio Argüello, dean of the Faculty of Agronomy at the National University of Piura (UNP), warns that the lack of water management, the persistence of illegal logging, and the absence of long-term funding limit the success of restoration initiatives.

He emphasizes that the main obstacle is financing. There is no prioritization for these types of projects; instead, investments tend to go to infrastructure or agricultural inputs. Moreover, the lack of clear incentive programs for communities—such as payments for ecosystem services—puts the continuity of activities at risk once external funding ends.

Finally, the absence of an integrated regional monitoring system prevents continuous assessment of real impacts on biodiversity, water infiltration, or carbon capture. To address this, Dean Remigio suggests the use of advanced technology.

“Although nature does its part in recovery,” he explains, “the speed of deforestation is much greater, creating a constant negative balance.”

For now, the dry forest breathes thanks to park rangers, community members, and volunteers who, like Gladys Huamán, plant hope where there was once only dust. In northern Peru, hundreds of people like her are planting the future again. These women and men understand that every new carob sprout is a way to breathe again—to reconcile with a land urgently calling for help.