A group of community members who navigate Amazonian rivers between Cochabamba and Beni use the Bufeo app, developed by Faunagua, to monitor the threatened species and track the region’s biodiversity. Journalist Nicole Andrea Vargas tells their story in this article, created with a Nature-Based Responses to Biodiversity Loss in Latin America Reporting Fellowship. This fellowship, from the Latin American Solutions Journalism Fund, an initiative of El Colectivo 506, was in turn supported by a grant from Earth Journalism Network and its Biodiversity Media Initiative. The article was published by Opinión on Oct. 26, 2025. It was adapted and translated here by El Colectivo 506 for co-publication.

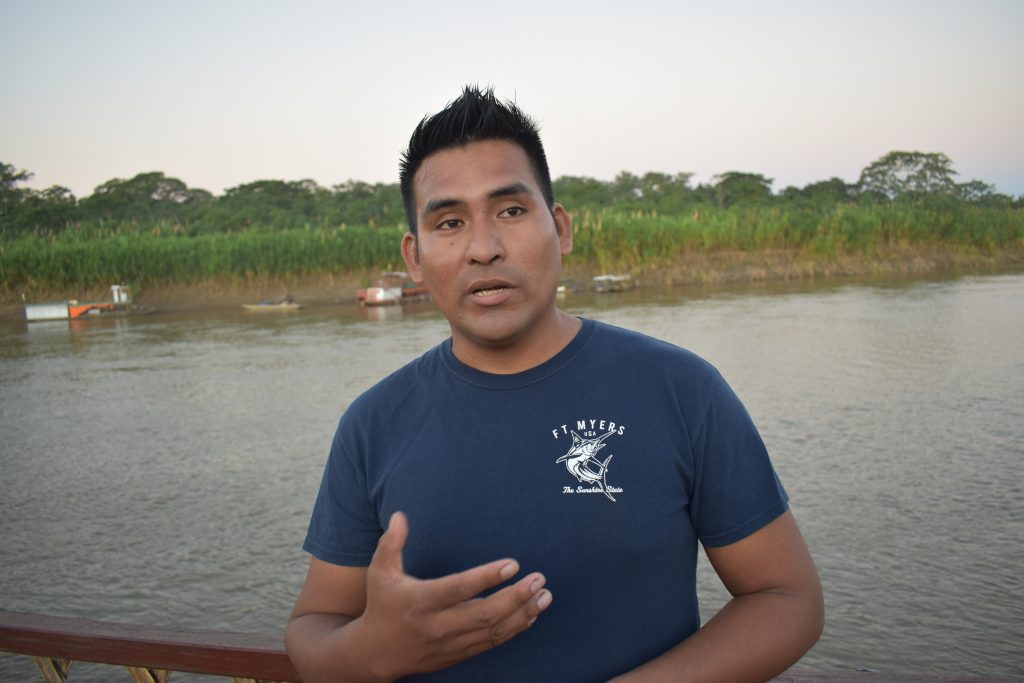

Jhonny Mendoza was nine years old when he saw a bufeo for the first time. He was amazed at the size of this freshwater dolphin, which can exceed two meters in length. He was aboard the boat belonging to his father—a fisherman from Puerto Villarroel, Cochabamba, Bolivia—navigating the Ichilo River in the early 2000s. That first encounter marked the beginning of a close bond with this aquatic mammal, which 20 years later would inspire him to promote citizen science through the use of the Bufeo mobile app, created to monitor this vulnerable species that inhabits Bolivia’s Amazonian rivers and faces multiple threats.

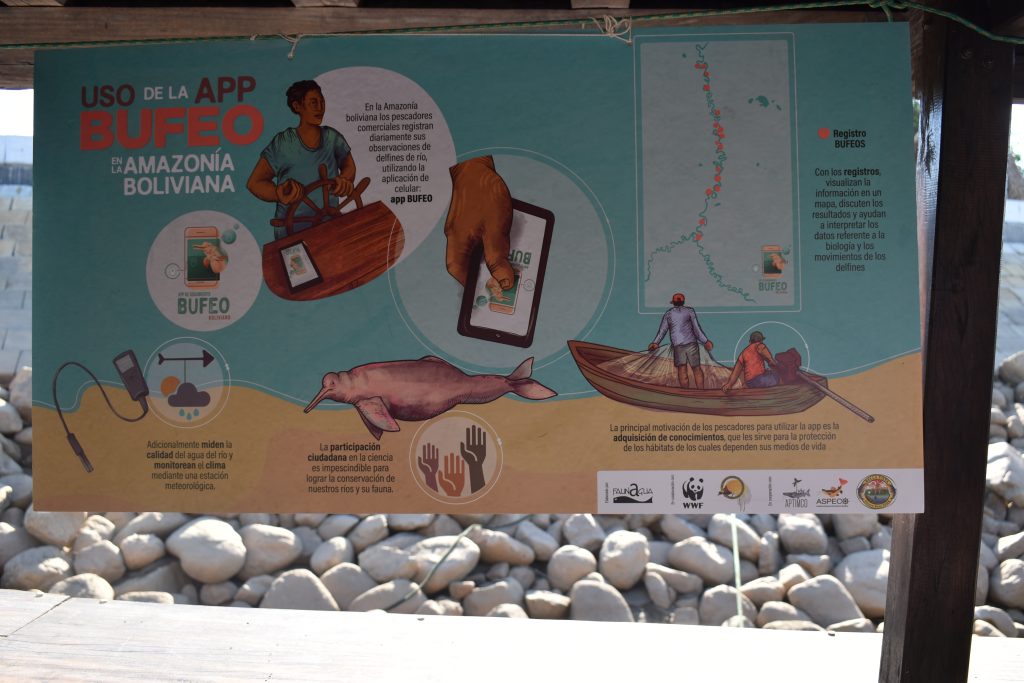

The bufeo (Inia boliviensis) is classified as Vulnerable (VU) according to the Red Book of Vertebrates of Bolivia. After decades of minimal conservation efforts, Faunagua became one of the first environmental organizations to study the species, launching protection projects and creating this app so that fishers—who share the river daily with the pink dolphin—could help safeguard it. They collect data for a mammal database and also measure water and air quality, since each boat carries a monitoring station.

The initiative began in 2010 with pilot counts by local communities, but it was fully consolidated in 2022. Jhonny was one of the first to use the app and help raise awareness among other fishers. Among the early results, the Second National Plan for the Conservation of the Bolivian River Dolphin – Inia boliviensis 2020–2025 was launched, along with a proposed Departmental Law for the Protection and Conservation of the bufeo in Cochabamba.

“When we get involved, we become defenders of the species because we see and learn that it plays an important role in the river. The bufeo must be conserved so the whole ecosystem functions well. They are the river’s guardians,” said Jhonny, 34.

A collapsing home

The bufeo (Inia boliviensis) is endemic to Bolivia, though approximately 20% of its population is also found in Brazil: it inhabits the Madera Basin, which includes the Mamoré and Iténez sub-basins.

Marine biologist and Faunagua Technical Director Paul Van Damme explains that this pink dolphin has two distribution areas in Bolivia. The first stretches from Puerto Villarroel, Cochabamba, to Bella Vista, Beni, where the Ichilo and Mamoré rivers meet. The second passes through Santa Cruz, along the Iténez River on the border with Brazil.

The Ichilo-Mamoré River is Bolivia’s “laboratory” for dolphin monitoring. Since 2017, expeditions have been conducted every three years to assess the bufeo’s status. Paul notes that a full population census is impossible, so scientists estimate numbers using the SARDI method—based on a scientific standard developed by the South American River Dolphin Initiative—allowing researchers across the continent to use the same technology.

The method involves two-level boats, with observers positioned at the bow and stern, each covering a 90-degree field of vision, while a recorder notes sightings. Six specialists participate in each SARDI expedition.

The bufeo, an emblematic species for Indigenous and rural communities, was considered a subspecies of the Amazon river dolphin (Inia geoffrensis) until 2006. However, studies—many led by Paul—determined it was distinct due to its habitat characteristics, earning it a Vulnerable classification in 2009. The species still awaits evaluation by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), which listed Inia geoffrensis as Endangered (EN) in 2018.

Jhonny, who has lived all his life in Puerto Villarroel, says the territory has undergone “tremendous” change from deforestation—causing river sedimentation—and pollution that harms fish reproduction and survival.

Paul explains that deforestation “changes the hydrological cycle” because rainfall hits the river harder, increasing runoff and causing more severe droughts in dry seasons.

With fewer riverside trees, there are fewer fruits for fish, which in turn affects the dolphins at the top of the food chain. “The Bolivian river dolphin is suffering from the lack of fish, just like the fishers,” says the Belgian biologist, who has lived in Bolivia for nearly 30 years.

A recent report from the University of Maryland’s GLAD Laboratory and Global Forest Watch (GFW) found that Bolivia ranks second in the world for native forest loss: in 2024 alone, it lost 1.8 million hectares of forest, 83% of it primary.

Fishers turn their facilities into information displays to spread knowledge about the importance of caring for bufeo. Nicole Vargas / El Colectivo 506

“Fish depend on the forest and vice versa. With deforestation, that relationship is broken, and the seeds of tree species no longer disperse. The system is collapsing, and bufeos depend on that interaction,” Paul adds.

In recent years, Bolivia has also suffered the worst forest fires in its history, placing it among the most affected countries worldwide. In 2024, more than 12 million hectares of forests burned.

During those fires, Jhonny volunteered to help extinguish the flames and protect his territory. He says air quality deteriorated and visibility worsened for his daily work.

“Many people think the main threat [to the bufeo] is fishing, but we’ve discovered that’s not the case,” says Paul.

These problems affect not only the bufeo but also local communities that rely on healthy rivers for their livelihoods, as well as the region’s biodiversity.

Community monitoring

In response, a group of fishers from 12 boats joined efforts to protect the species by using the Bufeo app, developed by Faunagua with funding from WWF-Bolivia.

Through this project, community members became “citizen scientists,” using their phones to record dolphin sightings and collect water and air quality data.

Paul calls the fishers’ participation vital because “they know the river best” and can gather data year round. It also raises public awareness of the need to protect local biodiversity. “With their knowledge, they become empowered,” he says.

The tool began operation in 2022 when eight fishers from Puerto Villarroel, including Jhonny, recorded 220 bufeos in the Ichilo River using the app. Since then, they have traveled more than 1,500 kilometers of Amazonian rivers, logging over 500 individual records.

These data improved understanding of the species’ distribution, abundance, and movement, and documented the threats it faces. The information is displayed on maps and discussed among fishers and scientists to interpret bufeo biology and design better conservation strategies.

Paul says satellite transmitters were also placed on eight bufeos with help from the fishers, who have experience handling aquatic species. The six-month monitoring period—the lifespan of the transmitters’ batteries—revealed that river dolphins can travel more than 300 kilometers in three months and move through both protected and threatened areas.

Jhonny recalls that was the first time he ever touched a bufeo. He had seen more than 100 individuals during his daily routes, but that experience deepened his commitment to using the app.

The bufeo’s conservation status serves as a “thermometer” for the region’s health, as this cetacean is considered the “sentinel of the Amazon.” Paul explains that its presence indicates underwater problems like invasive species or river pollution.

It is also a key climate change indicator, since it relies on “pockets”—small riverbank areas affected by dams or dredging—where mothers care for their calves.

In the past decade, bufeo sightings in Bolivia have doubled. In the 2013 expedition, researchers recorded three bufeos per 10 kilometers; in 2021, that number rose to seven. The latest expedition, in 2024, is still being analyzed, but preliminary results suggest between five and seven bufeos per 10 kilometers, indicating a total of 3,000 to 4,000 individuals in Bolivia.

“It’s an extremely sensitive species because it only has one calf every three years, making recovery from threats difficult. But we’re seeing more bufeos than in 2015, thanks to awareness efforts,” says the biologist.

The joint work between Faunagua and the Puerto Villarroel fishers helped implement the Second National Plan for the Conservation of the Bolivian River Dolphin – Inia boliviensis 2020–2025, which focuses on species conservation, cultural promotion, research and monitoring, communication, and legislation to coordinate protection efforts across institutions.

A proposed Departmental Law for the Protection and Conservation of the bufeo in Cochabamba is also under discussion, aiming to encourage participatory monitoring among fishers, Indigenous peoples, and biologists.

Fishing as heritage

Faunagua’s outreach also teaches fishers what to do if a bufeo gets caught in their nets. Jhonny says he once found a live dolphin tangled in his nets and released it—something “very rare because it’s such an intelligent animal that avoids the mesh.”

Flavio Guevara, another fisher who has used the Bufeo app since its launch four years ago, told Opinión that the project helped them better identify dolphins and distinguish mothers from calves.

On clear days, he says, he can see six or seven bufeos during his river routes. These sightings are added to the app’s database.

Flavio began as a fishing assistant over 25 years ago. After years of hard work, he bought his first 3,000-kilogram-capacity boat and became an independent fisherman. However, declining fish populations have made it increasingly hard to live solely off fishing.

His three sons continue the legacy, joining him on the boat. One of them, Adalid Guevara, first encountered the dolphins when helping attach the satellite transmitters. “Now we see more dolphins everywhere we go—they’re coming out to the river,” he says.

The project provides lessons that could serve as a model for other initiatives working with endangered endemic species. It shows that “citizen science not only complements traditional research,” Paul says, but also strengthens local ownership of conservation—key to long-term success.

During the latest expedition, the SARDI method was combined with the Bufeo app’s records. Preliminary results were positive, and experts now aim to expand the approach to other South American countries with river dolphins.

An environmental legacy

Faunagua’s project has faced challenges, especially limited funding. Paul notes that expeditions are costly, which is why they take place every three years.

Beyond financial hurdles, climate change and habitat degradation have made monitoring increasingly difficult, with poor visibility and shifting breeding zones among the obstacles.

These environmental issues directly affect the quality of life for riverside residents, who have had to adapt their livelihoods.

There is also ongoing outreach work with boat owners engaged in Amazonian tourism or unsustainable fishing, such as during veda—the breeding season, when fishing is prohibited.

Paul says the project’s most valuable lesson is the knowledge the fishers contribute through their experience. Jhonny and fellow leader Omar Ortuño will present technical and scientific data on the pink dolphin at the Third Congress of Ichthyology of Bolivia, on Nov. 26–28, 2025.

For Paul, who has spent much of his professional life studying Bolivia’s biodiversity, it will be a special moment—his final participation as a biologist. Since working with community members as children, his vocation has extended beyond science into social work. Leaving a legacy through these young fishers is part of his contribution to conservation.

That legacy also shapes Jhonny’s life. He says he works to protect the bufeo because he wants a better territory for his four children.

“I want them to see that I did something good for this community while I could,” he says. “Just like our parents did, now it’s our turn.”