Cispatá Bay is now a model of community restoration: a territory where former hunters protect the American crocodile, local associations restore mangroves, and more than 9,000 hectares are conserved through environmental, productive, and blue carbon initiatives. This chronicle reconstructs that ecological and social transformation through the voices of those who made it possible. Journalist Jose Ignacio Estupiñan Martínez tells his story in this report produced with the support of the Earth Journalism Network y and its Biodiversity Media Initiative, through the Latin American Solutions Journalism Fund, an initiative of El Colectivo 506. It was published by Voces que trascienden on Nov. 23, 2025 and has been adapted and translated for co-publication in El Colectivo 506. ChatGPT was used to create the first draft of the translation.

San Antero, on the coast of Córdoba, is a town of seafood and mangroves where life follows the ebb and flow of the tides. During the fur boom—the era when the exotic skin industry fueled a voracious global market—the skin of the American crocodile (caimán aguja, or Crocodylus acutus) became a luxury in Europe and the United States. Between 1950 and 1980, hunting was so rampant that authorities estimated that approximately 800,000 animals nationwide were killed.

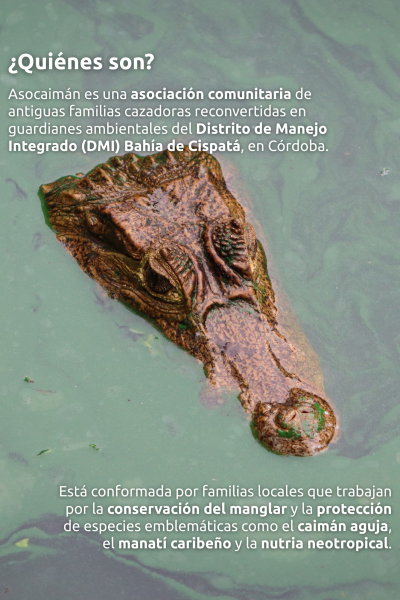

The hunters, whom everyone called caimaneros, sold not only the skins but also the meat and eggs. Decades of uncontrolled hunting left the species on the brink of collapse. At the end of the 20th century, a census by the Ministry of the Environment and the Humboldt Institute recorded a mere six specimens in the entire Cispatá Bay. Only tails and rotting heads remained on the shores: vestiges of a landscape where greed had suffocated life.

“The mouth of the Sinú River changed between the 1930s and 1940s; the impact was felt around 1960–1963. The bay ceased to be a delta and became an estuary: the salinity increased and the fauna changed,” recalls Ignacia de La Rosa, a mangrove worker and member of the Independent Mangrove Workers Association (AMI). She remembers both the transformation of the river and the traces of an economy that was sustained, for decades, by the exploitation of mangroves and caimans.

In 2003, biologists Clara Lucía Sierra and Giovanni Ulloa arrived at Cispatá Bay to conduct a new census. The found, not a thriving forest, but rather a species on the verge of extinction and a group of 18 hunters who still distrusted science.

“I was an illegal hunter for many years. There were 18 of us; today, we are the association that conserves the American crocodile in Cispatá,” recalls Betzabeth López, one of the first to trade his shotgun for nighttime census-taking. With the support of the Regional Autonomous Corporation of the Sinú and San Jorge Valleys (CVS) and the then ANH Corporation, scientists convinced them that only technical and orderly management could guarantee the survival of the ecosystems and, incidentally, the humans who live within them.

The transformation was not easy. Many mangrove workers and hunters resisted abandoning a profitable trade, and others feared that releasing caimans would provoke attacks in the waterways.

“It was very difficult to explain why they were going to be released, how we were going to coexist with them, and what the process would entail,” Betzabeth recalls. But the scarcity of animals and the violence surrounding poaching eventually convinced them. In 2004, they formally organized as Asocaimán. The CVS led the development of the protected area’s management plan, and the association began participating in its implementation: monitoring tours, environmental education, and community surveillance.

Unbeknownst to them, they were beginning the story of their own redemption.

Ranching and breeding: engineering to save a species

The conservation plan approved by the government was called “ranching and farm breeding”, a name that hid a simple and bold idea: rescue the eggs from wild nests, incubate them under control, raise the caimans until they were one meter tall (enough to defend themselves against birds and fish), and then return them to the mangrove.

“We build artificial nests with mangrove mud between October and November; then, between February and March, the females visit them and lay their eggs,” Betzabeth explains. “We collect the eggs and they incubate for 83 days at 31.5 °C. This way, we achieve about 70% females and 30% males.”

The program stipulated that one-tenth of the juvenile caimans should be released into the wild, while the rest were projected for future sustainable use, under a plan with two pillars: recovering the species through censuses and habitat management, and strengthening conservation with environmental education, community development and the creation of a protected area.

In 2016, after years of work, Colombia achieved consensus approval at COP17 from the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) for the sustainable use of the American crocodile in Cispatá, recognizing the scientific findings and the community’s commitment. Although current regulations criminalize hunting and there is no authorization for the commercial exploitation of the species, the process established the idea that well-managed conservation can pave the way for responsible use models.

Between 2002 and 2020, the conservation program achieved a remarkable recovery of the American crocodile population in Cispatá Bay. Thousands of eggs were collected and incubated under scientific supervision, and more than 12,000 hatchlings were released, transforming the mangrove forest—covering over 11,000 hectares—into a living restoration laboratory.

But the most significant change occurred among the people: former hunters were trained as technicians, schools integrated environmental education, and Asocaimán promoted ecotourism routes that transformed fear into pride. In 2020, this effort was recognized with El Espectador’s Bibo Award in the Species Protectors category.

The opening to sustainable harvesting sparked controversy. Some organizations feared that lifting the ban would reopen hunting, but the Humboldt Institute clarified that ranching only applied to eggs collected under controlled conditions and in georeferenced areas. With these safeguards, researchers and communities sought to maintain a balance between conservation and livelihood: ensuring the species’ survival while also guaranteeing the livelihoods of those who care for it.

Blue carbon as a motor for conservation

While Asocaimán was perfecting ranching techniques, the mangrove forest that protected the nests remained threatened by logging and the clearing of pastureland. The community understood then that without mangroves, there would be no caimans to save.

This local awareness, combined with the scientific expertise accumulated in Cispatá, coincided with a broader process: a group of institutions was seeking to demonstrate the climatic value of the mangroves in the Gulf of Morrosquillo.

From this joint work between the Institute of Marine and Coastal Research (Invemar), CVS, Conservation International, Omacha Foundation, and 14 mangrove associations, Vida Manglar was born. This is a blue carbon program that seeks to conserve more than 9,000 hectares of ecosystems in Córdoba and Sucre and, above all, to avoid greenhouse gas emissions associated with the loss of the mangrove.

The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) warns that most of the carbon in mangroves is stored underground in sediments rich in organic matter. When these sediments are disturbed by logging or drainage, they release that carbon suddenly into the atmosphere. Therefore, protecting and restoring these coastal ecosystems—mangroves, seagrass beds, and salt marshes—is crucial in the fight against climate change. The blue carbon market finances this protection, which is based on the mangrove’s capacity to retain large amounts of carbon in its biomass and soils for centuries

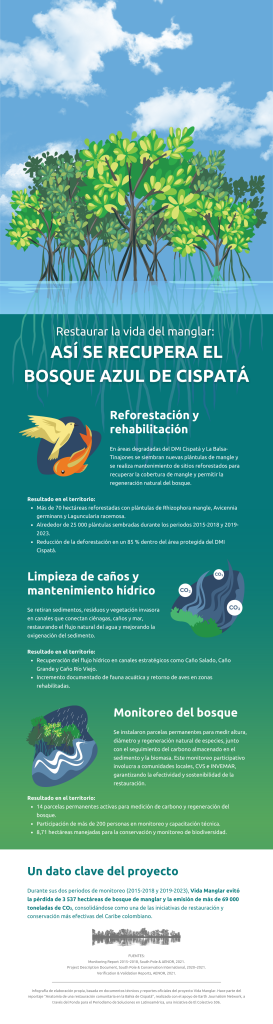

Vida Manglar was launched in 2015 as a pilot project by Invemar and CVS to measure stored carbon and avoided emissions through mangrove conservation and targeted restoration efforts. From the outset, the design and implementation were developed in collaboration with Conservation International, the Omacha Foundation, and community organizations.

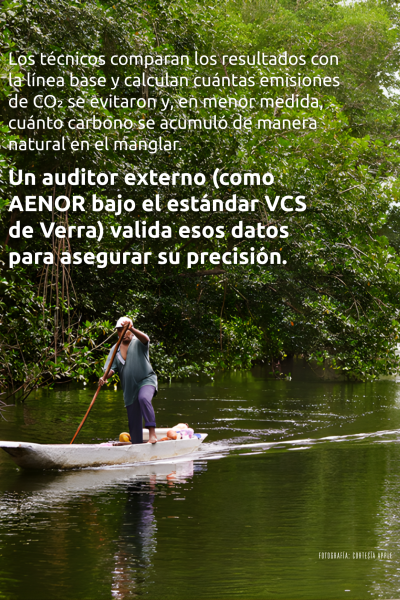

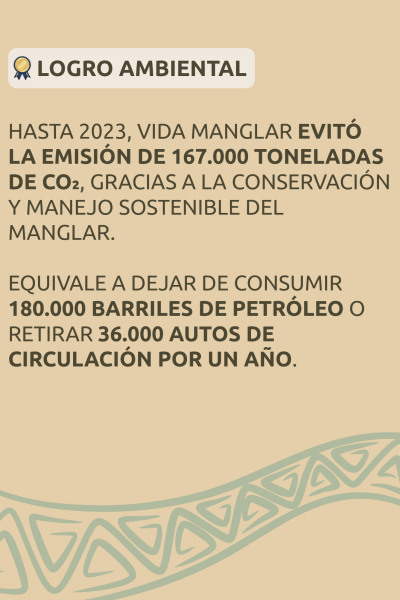

Between 2015 and 2018, the pilot project prevented the emission of nearly 69,000 tons of CO₂ and paved the way for strengthening the model. Specific contributions were added from companies such as Apple, and the firm South Pole was hired to provide technical services in structuring the project and preparing carbon reports. With the application of the Verra method, the project was consolidated in 2021 as the first certified blue carbon project in the Colombian Caribbean, with an estimated capacity to generate credits from avoided emissions each year.

The project measures the carbon stored in the soil and vegetation to quantify avoided CO₂ emissions—and, to a lesser extent, additional CO₂ that is captured—thanks to the protection of mangroves from threats such as deforestation and land-use change. Each ton of CO₂ equivalent is converted into a credit that is traded on the voluntary market. The resources are managed by Fondo Acción, the program’s managing entity, through shared decision-making between the Technical Committee, with community participation, and the Steering Committee. Thus, Vida Manglar combines scientific rigor with participatory management to ensure transparency and local benefits.

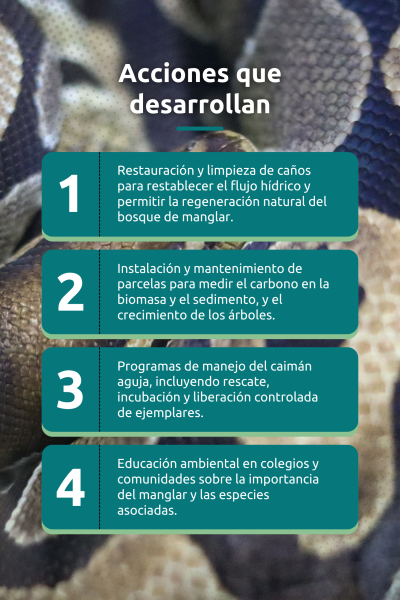

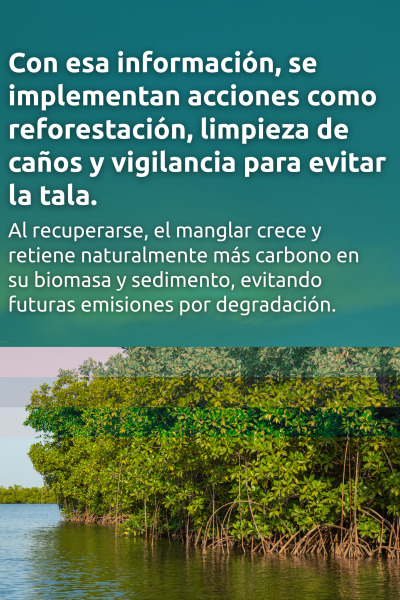

The program operates under four strategic lines: strengthening local governance, promoting sustainable production alternatives, restoring degraded areas, and implementing participatory monitoring. During fieldwork, teams made up of researchers and community members drill into the soil, measure biomass, and collect organic matter samples to analyze stored carbon. These samples, processed in laboratories in the city of Santa Marta, are translated into data that then supports the issuance of carbon credits and finances both mangrove conservation and the strengthening of the organizations that protect it.

The Vida Manglar monitoring program operates within a context marked by phenomena such as El Niño and La Niña, which affect rainfall patterns, tides, and salinity. While the program does not directly monitor these climatic events, it does incorporate available environmental and climate data to understand how they influence mangrove dynamics and the stability of stored carbon. According to its 2019–2023 report, the project has prevented the emission of approximately 168,000 tons of CO₂ since its inception. Today, 19 participating community associations—including Asocaimán, women’s groups, beekeepers, and artisanal fishers—have made the mangrove a source of science, livelihood, and hope.

The program demonstrates that science and economics can advance together, without losing sight of territorial equity. Its model stands out for its transparency: the bulk of carbon credit revenue is reinvested in communities and mangrove management, while a smaller portion covers administrative and technical costs. Between 2021 and 2024, the project’s financial projections show sustained growth in estimated credit generation, reflecting both the increasing demand for blue carbon projects and market volatility. In Cispatá, every revenue stream translates into concrete actions: community training in governance, restoration, and climate change; strengthening local associations; and supporting productive initiatives linked to the mangrove.

According to official projections registered with Verra in 2020, the project estimated annual revenues from the sale of carbon credits of $84,240 in 2021, $89,529 in 2022, $103,473 in 2023, and $113,226 in 2024. Although these figures correspond to projected scenarios and not actual sales, they allow us to understand the financial scale planned to sustain activities such as the restoration of waterways, ecological research, and the strengthening of community organizations.

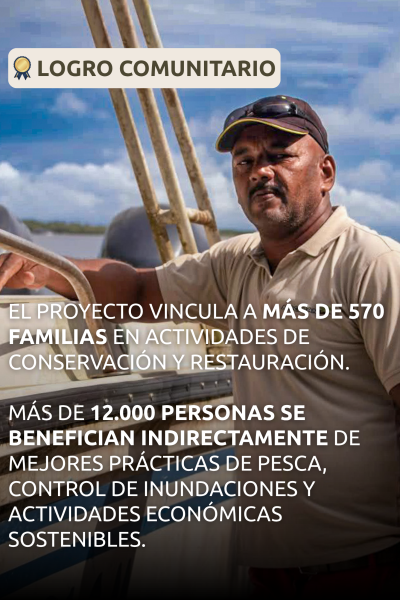

The results are tangible. According to the World Economic Forum, 435 families have received financial incentives, and more than 100 workshops have been held with nearly 1,000 participants, 42% of whom are women. Program resources have helped strengthen monitoring processes for emblematic fauna such as the American crocodile, the manatee, and the otter; they have also helped consolidate partnerships with research centers like the Cispatá Marine Research Center (Cimaci), where American crocodile eggs are incubated and ecosystem research is conducted. The Ministry of Environment estimates that the project will require approximately $6.9 million over a decade.

Between 2019 and 2023 alone, communities cleaned 34.6 kilometers of waterways and restored more than 1,000 hectares of salt flats and degraded areas: an effort that is giving back water, life, and hope to the mangrove forest.

Knowledge, trade, and local organization

Betzabeth López, the former caiman hunter, learned to distinguish the sex of the eggs by their size and texture. Today, he teaches young people how to operate incubators and conduct nighttime censuses in the Cispatá waterways.

Meanwhile, Ignacia de La Rosa, a member of the Independent Mangrove Association (AMI), recalls that, along with other women leaders, she advocated for the restoration of the natural waterways and learned to follow the tides to recover the former water flows.

Asocaimán, the association of converted caiman hunters, has 18 members and a growing group of volunteers who work from the Amaya Biological Station, focused on caiman conservation and community ecotourism.

The men and women of the association travel along waterways and swamps to measure temperature and salinity; record sightings of caimans, manatees, and birds; and work with biologists to determine how many eggs to collect each season. They also lead environmental education programs in San Antero and Lorica, where they teach children that the caiman is not an enemy, but rather an essential part of their territory and identity.

The second monitoring report of the Gulf of Morrosquillo Blue Carbon Project—Vida Manglar (2019-2023), published in January 2025, indicates that more than 170 families have been trained in restoration and participatory monitoring, and that 20 demonstration plots have been created. The workshops range from mangrove species identification to meliponiculture, the art of raising stingless bees. In community nurseries, residents collect propagules, plant them in baskets within the nurseries, care for them for months, and then transport them in biodegradable bags to the field, where they are used as part of the mounding technique to rehabilitate the salt flats.

Meanwhile, other associations such as Apisanantero, Asomiel, Apracag, and Covicompagra are diversifying their products: they produce honey, candles, and wines that they sell to visitors, strengthening the family economy. Asocaimán collaborates with them through ecotourism routes, interpretive tours, and environmental education programs that connect the history of the caiman with the new mangrove economies.

Thanks to these efforts, Vida Manglar has made Cispatá a global leader. Its experience has been presented at more than 30 international conferences and forums. In 2023, for example, Ignacia de La Rosa traveled to Dubai to represent her community at COP28. There, she described how the women of the mangrove forest participate in data collection, reforestation, and honey production. Upon her return, she led workshops for other women on community project management and participation in the program’s decision-making processes, reinforcing the idea that climate action is also built from the ground up.

Caring for the mangroves, Ignacia says, is both a physical and emotional task. Before planting, the communities organize community workdays to clean the channels that connect the forests to the sea, removing sediment and fallen logs so the water can flow freely again. Then comes the most anticipated moment: planting.

“It’s so beautiful to water those seeds,” she says, “and when you come back two months later, they’re no longer lying flat but standing upright.”

In Cispatá, everyone contributes their talents: some are skilled navigators, others observe birds or control fires. The elders preserve traditional recipes to offer along ecotourism routes. In schools, teachers integrate these experiences, and children learn that caimans are not enemies, but a living part of the land.

In recent years, visitors from some 30 countries—scientists, officials, tourists, and members of indigenous communities from other regions—have come to learn about the project and share their experiences. More than revenue from tours or products, this exchange has sparked a deep sense of pride.

“Every time I plant a tree, I feel like I’m planting the future,” says Luis Roberto Canchila, legal representative of the La Balsa Mangrove Environmental Association in San Bernardo del Viento (ASOAMANGLEBAL). This conviction now drives the goal of replicating the experience in at least six areas of the Colombian Caribbean.

The blue carbon debate

Although Vida Manglar is recognized as a model that avoids carbon emissions through mangrove conservation and incorporates ecological restoration actions to ensure the sustainability of the ecosystem, its approach also raises questions.

An article from the Degrowth platform warns that selling carbon credits can commodify ecosystems and subject communities to market volatility. According to the author, the so-called blue economy sometimes reproduces colonial logics: countries in the Global North buy their right to pollute, while those in the Global South take on the task of protecting forests. The article also criticizes some international organizations for appropriating local knowledge and transforming it into mere commercial value, stripping it of its political and social dimensions.

Along the same lines, fears persist about the future of the American crocodile. Environmentalists point out that legalizing the trade in skins, if authorized in subsequent phases, could lead to abuses or pressure to increase quotas, while authorities maintain that the management plan and CITES safeguards impose strict controls. The debate remains open: between those who see these projects as an opportunity for sustainability, and those who warn of the risk of reducing nature to a negotiable commodity. For now, Colombian law maintains that hunting is a crime and prohibits the commercial exploitation of the species in Cispatá.

The volatility of the carbon market is also a cause for concern. Experts from the Innovation Forum point out that blue carbon projects need stable contracts, clear rules, and public policies that guarantee the rights of communities and prevent the concentration of profits in the hands of intermediaries. For organizations such as Asocaimán and the mangrove associations, these are not abstract discussions: their sustainability depends on maintaining a balance between economic activity and conservation.

“We know the world is watching us and that any mistake could set us back,” says Betzabeth. “That’s why our priority is still to release caimans and restore mangroves; if the door ever opens to more exploitation, we want it to be with respect, transparency, and under clear rules.”

The success of Vida Manglar is not without its downsides. In 2024, the Constitutional Court of Colombia ruled against a carbon credit project on the Pirá Paraná River for violating the rights of Indigenous communities by failing to consult them. That same year, journalism investigations questioned South Pole and AENOR—companies that have provided technical services to carbon projects, including Vida Manglar—about alleged irregular land purchases in Honduras and other countries. These cases fueled distrust of the carbon market and reinforced calls for transparency and community participation.

Ecologist Sandra Vilardy recalls that Vida Manglar did not emerge from a foreign office, but from more than three decades of local organization and restoration in the Gulf of Morrosquillo: “The sale of bonds is only the last phase of a long road, made of community empowerment.”

The paradox is clear: it’s a project born from the grassroots that, at the same time, depends on certifications and international companies. Therefore, maintaining a critical perspective is as essential as protecting the mangrove.

“Vida Manglar belongs to us; nobody brought it here. We were here before. Outsiders came to continue processes and provide tools,” says Ignacia de La Rosa, reaffirming that the true authorship of the project belongs to the communities that made it possible.

GALERÍA 4

From the waters of Cispatá to the sunset over the gulf, the American crocodiles once again dominate their territory. Their presence marks the triumph of a community that has learned to coexist with them. Courtesy Jose Ignacio Estupiñan Martínez y Estefanía Contreras Betancourt / El Colectivo 506

On the banks of the Sinú River, children watch a juvenile caiman slither through the mangrove roots, while veteran hunters recount the old wars fought over an animal that was once on the verge of being forgotten. Today, instead of hides, they display seed necklaces and jars of honey; community work crews clean irrigation ditches so that seedlings can breathe and fresh water can flow again. Every gesture reveals a shared purpose: to reconcile the community with its land and demonstrate that conservation is also a way to heal the collective memory.

The return of the American crocodile confirms that well-managed ranching can save a species, and that carbon credits—with clear rules, transparency, and social justice—can help finance the protection of entire ecosystems. As evening falls in Cispatá Bay, the sun paints the mangrove treetops gold: a reminder that life only endures when there is a balance between species and people, between economy and memory, between development and dignity.

————————————

Disclaimer:

This report is part of the research project “Mangrove Life: A History of Conservation and Economy from Cispatá Bay.” Its content was independently produced, based on community testimonies and official documents from the Mangrove Life project, implemented by Conservation International Colombia, CVS, INVEMAR, the Omacha Foundation, and local mangrove associations. The opinions and conclusions expressed are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the organizations mentioned or the funders.