Our February edition, “Long Live CR!”, is all about the healthy aging of Costa Rica’s people—and we’re just as obsessed with the health of Costa Rica’s democracy. The presidential and legislative elections this past Sunday was a checkup.

So how’d we do?

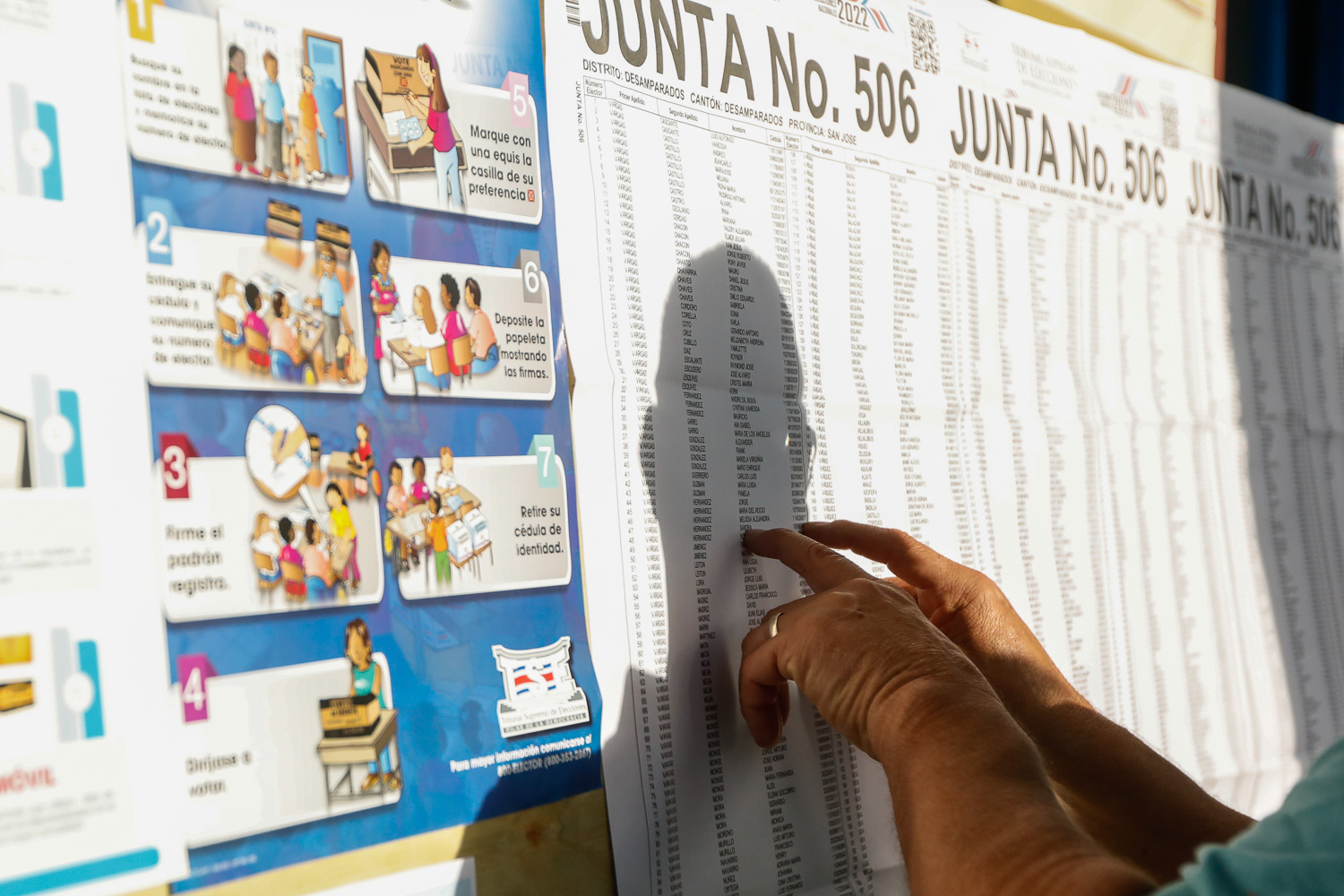

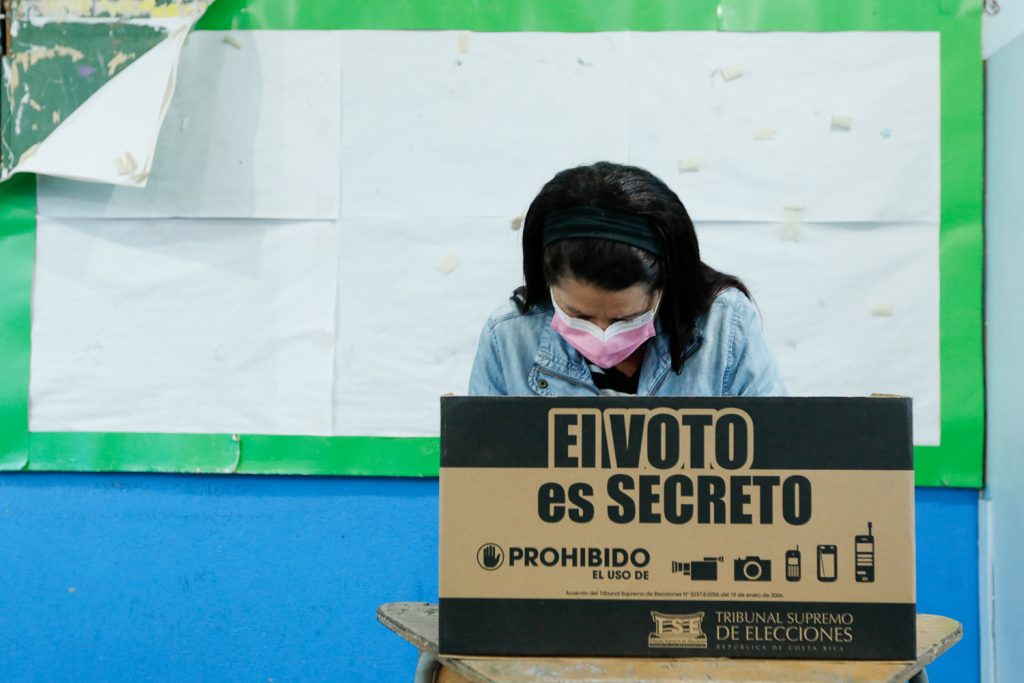

First, the good, which probably seems so ordinary to all Costa Ricans—as it should—and so extraordinary to outsiders like me. Just the word “ordinary,” for starters. Routine. Calm. Cars with different party flags waving from different windows. Efficient vote-counting. National percentages that tick up and down as increasing numbers of voting centers report. Concession and victory speeches that flash across the screen. Everyone in bed by midnight.

Seriously, this demands a beat. A pause.

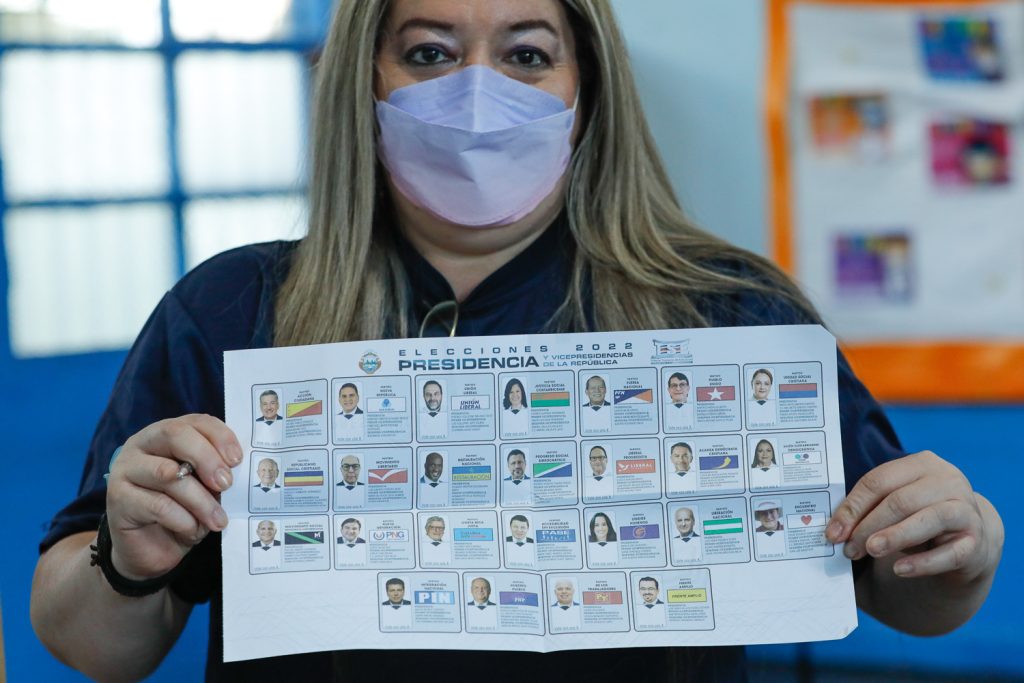

Did you take a deep breath? Now for the rest. Historically high voter abstention. How could it be otherwise, with not just a pandemic, not just cynicism and exhaustion, but also 25 candidates to choose from? In a system designed for two opponents, where the primary election has become a sort of presidential primary, is it surprising that hundreds of thousands of Costa Ricans said, in effect, “Wake me up when there are two left?”

Well, there are two left. From that field of 25, the two still standing are arguably the two who drag along the heaviest baggage, almost as if the election had blown the other candidates away. One is a surprise; one was all but inevitable from the start. One’s baggage includes a sexual harassment case. Rodrigo Chaves was “demoted—but not fired—despite a documented pattern of harassment that lasted at least four years and involved six women,” according to the Wall Street Journal. The same article indicated that a 2021 review by the World Bank of the 2019 case determined that these sanctions against Chaves were insufficient.

The baggage belonging to José María Figueres Olsen include the investigation against him in 2004 for allegedly receiving $906,000 for a consultancy related to the French telecommunications firm Alcatel (Alcatel and alleged payoffs related to its sales to the Costa Rican Electricity Company were at the heart of one of the two massive corruption scandals that erupted that year involving three former Costa Rican presidents). President from 1994-8 and son of three-time president José María Figueres Ferrer, “Chema” evokes powerful, and often deeply negative, reactions. But let’s let him tell it in his own words: in 2016, he took out a newspaper ad inviting members of the general public to an open session to say anything they liked to his face. “Today I’m here to converse with those who call me a thief, liar, corrupt, coward, ‘cara e barro‘, cynical, shameless, cascarudo and even a son of a bitch,” he wrote.

«Hoy vengo a conversar con quienes me dicen que soy ladrón, mentiroso, corrupto, cobarde, ‘cara e barro’, cínico, sinvergüenza, cascarudo y hasta hijueputa»

Costa Rica’s meme-iverse has already gone wild. One, widely circulated on Monday, compared the upcoming April 3rd runoff to a walk through San José: “Do I want to get robbed, or felt up?”

Meanwhile, throughout the night, the legislative results flashed across the screen: the news about the people who, together, will wield more muscle than the president, but whose election is always presented as an afterthought in the shadow of the presidential results.

Our March edition will dive deep inside that process and its impact. For now, we’ll just mention that Chaves’ brand-new Social Democratic Progress Party had a surprisingly strong showing (nine), but the country’s two traditional parties, Figueres’ National Liberation (18) and Social Christian Unity (11), reasserted their dual positions at the top. As usual, former presidential candidates who’d double-dipped by also putting in their names as legislative candidates were elected as legislators, including third-place finisher Fabricio Alvarado (New Republic, seven) and Eli Feinzaig (Liberal Progressive Party, six). The Frente Amplio rounds things out with six legislators.

How did you experience February 6th, 2022? What are you worried about, angry about, proud of?

If you were invited to an open session right now with the two remaining candidates and your legislators-elect, what would you have to say?

Send us a text or audio at 8506.1506, or email us at [email protected]. We’re hard at work to create a March edition full of perspective, information, reflections and voices. We’d love for yours to help shape it.