Thousands of women are taking on vital and invisible domestic work. Innovative policies like Manzanas del Cuidado (Caregiving Blocks) in Bogotá, Colombia, offer support and recognition, but cultural changes are still needed. Journalist Camila Ramírez tells the story of the “blocks” in this piece created with a Gender Equity Reporting Fellowship from the Latin American Solutions Journalism Fund, an initiative of El Colectivo 506, thanks to a donation from the Solutions Journalism Network and the Hewlett Foundation. The article was published by El Turbión on May 18 and has been adapted and translated here by El Colectivo 506 for co-publication. Please note that the translation has been edited for clarity and cultural context.

In Bogotá, thousands of women have had to postpone their personal, academic, and professional projects indefinitely in order to take on—by social mandate—unpaid care work in the home, community, and society. This is nothing new, of course. Entire generations of women have dedicated their lives to care work without economic or social recognition.

Myreya Jiménez, a mother and resident of La Candelaria, expresses the reality shared by many women in Bogotá:

“We’re constantly caring. Every day we live for caring. […] All women have the stigma that we only care, and it’s unpaid.”

Housework extends from early morning until late at night and is essential to the functioning of daily life: domestically, socially, and economically. Despite its importance, this work remains invisible and lacks remuneration and cultural recognition in the country.

Blanca Diva, a 51-year-old mother who spent years as a homemaker, divides her experience as a caregiver into two stages: first caring for her children, and now for her mother. In both, she has seen how the emotional toll of caregiving translates into health problems.

“I’ve been a full-time caregiver for my disabled mother since she contracted meningeal tuberculosis in 2023. I left home at 7 AM and returned at 7 PM, always exhausted. Chronic stress caused me to develop fibromyalgia. When you don’t sleep, your entire immune system collapses.”

This is confirmed by Ana Victoria, a woman who has been providing care from an early age and lives in Santa Fe: “I’ve been a caregiver since I was seven years old. I started by taking care of my little brothers and sisters and taking care of the house because my parents worked. Then I started a family and took care of my children. Now, more recently, I’ve taken care of my grandchildren.”

According to Ana Victoria, this experience profoundly marked her childhood. From a young age, many women are forced to assume adult responsibilities—not by choice, but because they are socially and culturally expected to contribute to household chores.

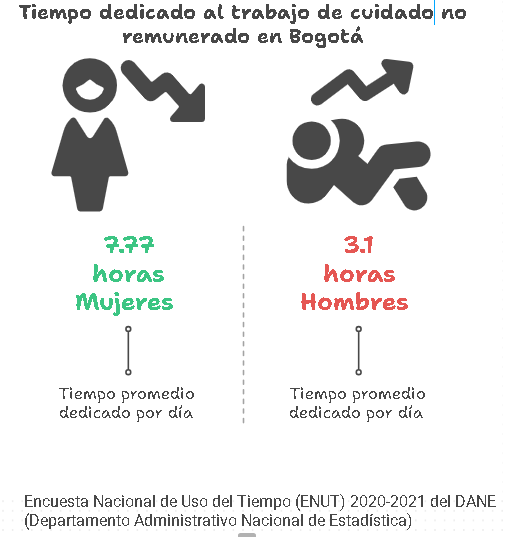

Many of these women belong to Colombia’s lowest income strata (1, 2, and 3), which exacerbates their vulnerability. In Bogotá, poverty and inequality in the distribution of care work reinforce these women’s precarious conditions. Data from the 2020-2021 National Time Use Survey (ENUT) tell the story:

Easing the burden on women caregivers

While Care Economy Law (Law 1413, 2010) marked a milestone in recognizing unpaid care work and its contribution to the country’s economy, Bogotá’s caregivers say that they felt this measure was insufficient to meet their daily demands. In response, women’s groups in the capital have raised their voices to demand public policies specifically aimed at women who perform care work in the city.

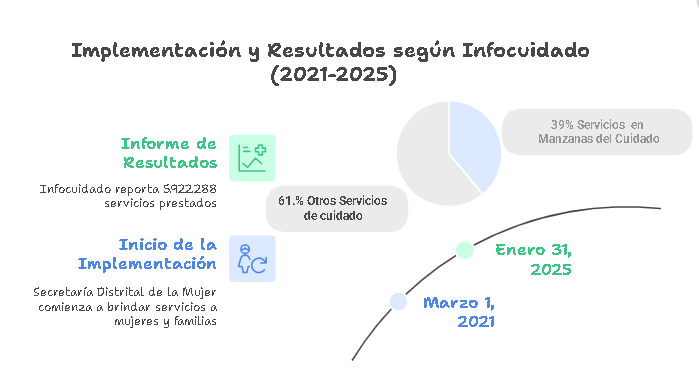

After years of pressure from feminist organizations and women’s groups, Bogotá implemented the District Care System in 2020, a pioneering model in Latin America for recognizing unpaid work. It was consolidated as part of the Territorial Planning Plan (POT) 2022-2035, which incorporated it as a strategic pillar to reduce the urban inequalities that historically affect on women caregivers.

Sharon Figueroa is part of the technical support team of the Intersectoral Commission of the District Care System. She highlights one of the system’s main strengths:

“The power of the District Care System lies in its city-wide approach. …It is designed for women who perform care work, but also focuses on people who require care. It has a gender perspective, but also serves populations such as girls, boys, people with disabilities, and the elderly.”

Recognizing the need to support caregivers, mostly women, Bogotá created the Manzanas del Cuidado, or “Caregiving Blocks” [editor’s note: manzana means “apple” in Spanish, which the program’s logo playfully incorporates, but is also slang for a city block in several Spanish-speaking countries]. This strategy became the cornerstone of the District Care System, an innovative model that seeks to transform the city through urban co-responsibility with a gender perspective.

Manzanas del Cuidado are strategically located spaces throughout the city that offer free services to reduce the burden of unpaid care work. At these centers, caregivers, primarily women, can access multiple benefits such as completion of primary and secondary education; training programs; spaces for rest and exercise; and legal and psychological counseling.

This innovative model seeks not only to support caregivers but also to free up their time by concentrating various services in a single location. Through its services, it seeks to reduce the time spent on housework, provide opportunities for caregivers’ personal and professional development, and facilitate access to community support networks. The sites also offer training on human rights and economic autonomy. This model represents a significant advance in social co-responsibility for caregiving.

Sharon explains the criteria for establishing and strengthening Manzanas del Cuidado, including the application of a prioritization index. This tool incorporates a comprehensive sociodemographic analysis, allowing implementers to identify the areas of greatest need for these services.

“The feminization of poverty is one of the main issues to be considered. Factors such as rates of gender-based violence, the percentage of women engaged in unpaid care work, and the availability of services in each location are assessed. These data emerge from a comprehensive territorial assessment, which then becomes a prioritization index.”

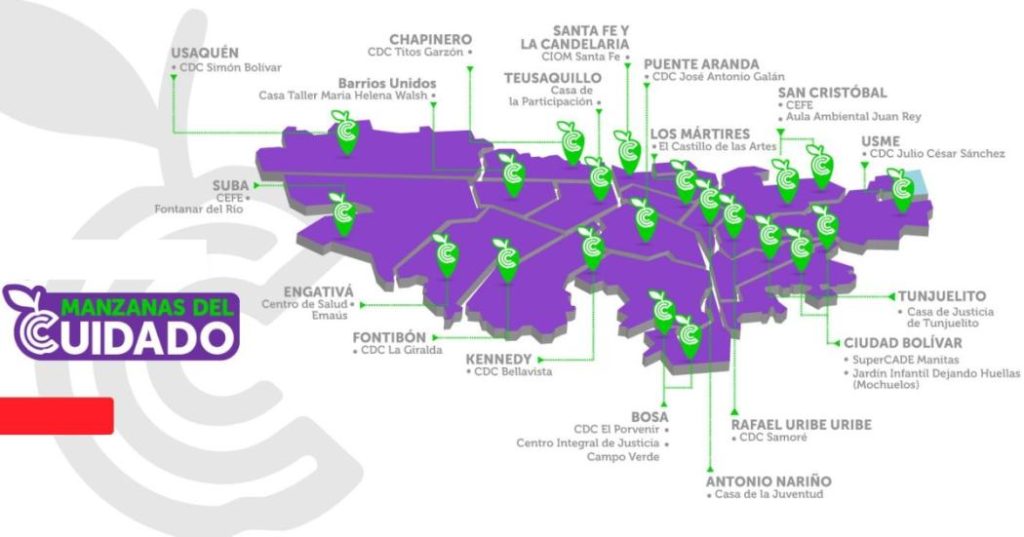

Today, Bogotá has 25 Manzanas del Cuidado distributed throughout the city’s public spaces. The Manzanas are located in Community Development Centers, belonging to the Secretariat of Social Integration; Participation Centers; Youth Centers; Happiness Centers (CEFE); and SuperCADE. These existing spaces were selected and repurposed in various locations to offer gender-sensitive services, optimizing resources for the benefit of women caregivers and their families.

The long-term goal is to expand the network to 45 Manzanas del Cuidado, ensuring between one and two per territory. As Sharon Figueroa explains:

“Our goal is to extend the Manzanas del Cuidado model and the District System to all of Bogotá. By 2035, through strategic territorial prioritization, we will reach the planned 45 units.”

The maintenance of the Manzanas del Cuidado is provided through agreements that guarantee their operation and sustainability in each neighborhood. A key example is the Inter-Administrative Agreement 913202, which coordinates intersectoral services from entities such as the Ministries of Health, Social Integration, Education, Economic Development, Culture, Recreation and Sports, Environment, Government, and Planning, among others. Each of these institutions provides specific resources and services for the maintenance of the Manzanas del Cuidado.

The District Women’s Secretariat acts as the lead institution, coordinating all of the district entities involved. It is also responsible for hiring staff for the daily operations of the Manzanas del Cuidado. This includes a technical team, coordinators, psycho-legal teams, trainers, and other professionals. In this process, priority is given to selecting women with a gender perspective and regional knowledge, thus ensuring comprehensive attention to the needs of caregivers and their families.

The local roundtables of the District Care System have also become a key mechanism for the local implementation of decisions of the Intersectoral Commission and the Technical Support Unit (UTA), composed of district entities. These participatory spaces have made it easier to identify community needs, as well as to address the challenges faced by Bogotá women in terms of care work.

Sandra Ausique is the coordinator of the Manzana del Cuidado in downtown Bogotá, which serves the communities of La Candelaria and Santa Fe. In her role, she explains how the coordination process is carried out to bring care services to different neighborhoods:

“The Technical Support Unit (UTA) is the main body of the District Care System, where the secretariats define the services they will offer in each block. From there, local roundtables emerge, allowing us to join forces with the community to verify that the commitments and services are being implemented and that we are reaching women caregivers.”

As coordinator of the Manzana del Cuidado, Sandra Ausique highlights the fundamental role of the Technical Support Unit (UTA) and local committees in evaluating existing services and creating new ones. A concrete example is “The Art of Caring for Yourself,” an initiative that emerged from this participatory process of evaluation and collective creation. She explains:

“”The Art of Caring for Yourself,” a program run by the Secretariat of Social Integration, was created after identifying that many women were attending the Manzana del Cuidado accompanied by their children. To facilitate their access to services, this space was created where children are cared for by professionals, allowing mothers to participate in activities with peace of mind.”

The Manzanas de Cuidado showcase the transformative impact of women caregivers. Through their various services and training programs, they have significantly strengthened the autonomy and personal development of these women, as well as empowerment and growth. Blanca puts it this way:

“I was impressed that the advertising was so focused on women. That wasn’t something we saw before, right? At least here in Bogotá, Colombia… Then we started to notice that these were spaces where a lot of women showed up, and it was really nice to meet other women there. The spaces for talks and training are wonderful.”

A respite for women: autonomy and empowerment

Among the activities most valued by caregivers are physical activity, which range from therapeutic exercises to yoga, dance sessions and the bike school. Ana Victoria, a user of the downtown Bogotá Manzana del Cuidado, says enthusiastically:

“I didn’t know how to ride a bike. I’m 65 years old, and that was unthinkable for me. The day I learned, I cried with joy. …It’s been very satisfying for me, because I’ve awakened my motivation and also freed myself from many burdens. Now I’m truly doing what I love.”

Access to various services has allowed women to understand the importance of self-care and continuing their studies, aspirations, and dreams. Sandra Ausique highlights the positive impact that completing secondary education has on women:

“Receiving their high school diploma is something very meaningful for them. It empowers them and allows them to dream again. It has been a very rewarding experience… Many women arrive with difficult life stories, but the opportunity to complete high school brings them happiness and a new perspective for their future.”

Ana Victoria says the programming has motivated her to explore new activities. On Saturdays, she attends La Concordia School, a complementary facility at the downtown Manzana del Cuidado, where she participates in the flexible education service. She says:

“For two years now, I’ve been fulfilling my dream of finishing high school. The Manzana del Cuidado school gave me this opportunity. I’m now in tenth grade, and it’s been a wonderful experience. I’ve learned many things, but the most important: I must love myself. Me first, me second, me as a priority.”

Like Ana Victoria, Carmen Rodríguez, 69, is a participant in the flexible education program at the Manzana del Cuidado Manitas, in Ciudad Bolívar. For years, two factors disrupted her academic and professional development: her multiple disabilities, and her family care responsibilities. She recounts her experience:

“I dropped out of school because of my disability and to dedicate myself to caring for my children and grandchildren. Now, I’m back in school. I attend flexible education and am completing my baccalaureate degree. I even dared to take courses in systems, trapillo [to crochet with recycled cloth], and weaving. I attend whenever I can because this has become my driving force in life.”

Carmen attends with her daughter, who has become a vital support: “When I’m with my daughter, the activities aren’t as difficult, but without her, I feel discouraged.” Carmen also says that “it’s difficult having to explain my disability to others.”

For Myreya Jiménez, a user of the downtown Bogotá Manzana del Cuidado, books have become a key tool for her personal growth. Through reading, she has not only rediscovered her value as a woman, but also strengthened her autonomy. She describes her transformation as follows:

“I’m very grateful for the reading room. The books helped strengthen my self-esteem, reinforce that power within me—those qualities I had, but hadn’t even realized in myself. It’s taken away that fear of doing things for myself.”

The Manzanas del Cuidado have gradually transformed the lives of women caregivers, offering them not only training opportunities but also a space where they feel recognized and valued. Ingrid Carvajal, coordinator of the Manitas Manzana del Cuidado, explains:

“Female participation is constantly increasing. Women are empowered by finding various educational activities, information about their rights, and most valuable, a space to unwind and breathe.”

Improving recognition and support networks

Physical and emotional overwhelm and social invisibility profoundly affect women caregivers, manifesting in a high rate of both physical and psychological illnesses. Angie Sánchez, a psychologist on the psycholegal team at Manzana del Cuidado Manitas in Ciudad Bolívar, explains this problem:

“They talk about this overload from the hours involved in caregiving, and we realize that this has physical consequences, that there are psychosomatic illnesses. A large number of women suffer from fibromyalgia, arthritis, chronic stress, and burnout syndrome, which are closely related to their emotional state.”

This health issue is closely linked to the historical invisibility of care work on one hand and, on the other, to the lack of spaces dedicated to women caregivers. Angie Sánchez, from her experience in consulting, has identified multiple unmet needs:

“One of the greatest needs is the need for listening spaces, because most caregivers are in the caregiving role all the time. In some ways, it becomes a space for relief. There are also needs for health care, needs for rest and respite, and needs for training spaces.”

Blanca, user of the Manzana del Cuidado in Juan Rey, recalls how, during the years she spent caring for her children, she experienced sleep deprivation and constant exhaustion. Today, she understands that this exhaustion was linked to physical and psychological violence.

“Due to so many emotional issues with my children’s father, I didn’t sleep enough and even developed chronic gastritis. Now I realize it was all a product of that terrible emotional burden I carried, so much pent-up resentment, …when you’re hit, when you’re humiliated and feel your dignity trampled.”

Most women seek counseling from psycho-legal teams for a variety of reasons: from enforcing rights with the EPS for their dependents, to seeking help filing complaints for issues such as child support and physical and psychological violence. However, the main demand among women caregivers is the opportunity to be heard. Angie Sánchez emphasizes the importance of these listening spaces.

“The exercise of venting and listening is very transformative, because they feel it’s a safe space where we’re not questioning what they’re saying. Their story is important. It’s a space of trust, but above all, we can also be part of the support network they need.”

Blanca says that being listened to saved her life. It motivated her to seek solutions for her and her mother’s health problems. She recalls that in the psycholegal consultations and forums for caregivers, she found empathy, active listening, and the inspiration she needed.

“Seeing my mom in bed every day, I thought, ‘This is what my children will experience because of my fibromyalgia.’ These questions led me to want to free them from my illness. At one of my appointments, when I confessed, ‘I want to die,’ she asked me, ‘Do you really want to die, or do you just find no meaning in your life?’ That question made me reflect. By the end, I realized: Yes, I want to live, but I need to find meaning in my life, and I’ll work on that.”

For Blanca and other women, consultations with psycho-legal teams have allowed them to acquire both legal and psychological tools. In Blanca’s case, she says that for years she tried to seek support from the EPS (Health Service) and other government agencies, but found it impossible to access certain services, and the tools offered were limited. She adds:

“Here, I found care designed for us. For women. When I attend a talk or a consultation, I find empathy, quite the opposite of what I find at the EPS, where I encounter an employee who sees me as just another statistic, just another number.”

These support networks have not only provided legal and psychological tools but have also encouraged women such as Yesenia Martínez to take on active roles in their own communities. Thanks to the support of the Manzanas del Cuidado, some participants have gone a step further, becoming program employees. Yesenia, 31, demonstrates this when she says:

“I’ve been my son’s caregiver since I was 16. I was a young mother, but before that, we were 11 siblings, and as a girl, I had to help out at home. …Before arriving at the Manzana del Cuidado space, I believed my destiny was to work, take care of my son, and get ahead, and that was it.”

The program not only provided her with psychosocial support and digital training, but also offered her a job, allowing her to break the cycle of unpaid caregiving she had been experiencing since she was 16. Today, Yesenia transforms her personal experience into support for other women, guiding them through her own testimony.

“I arrived at La Manzana, finished high school, and for the first time, I felt heard and valued. I learned office tools—which I didn’t have, because there were no computers at my school—and although I cried every day during my marketing technologist program because of my lack of knowledge, I succeeded. When I was selected to work here, I couldn’t believe it… and today, as I graduate, I use my story to show other women that it’s possible. That it’s the beginning of a path where many things can be achieved.”

Yesenia’s comments suggest that decentralizating caregiver services is promoting a more equitable urban model. Because the services offered by the Manzanas del Cuidado are no longer concentrated in specific areas, but are extended through various neighborhoods, it promotes equity among different areas and ensures that all caregivers, regardless of their location, have access to development opportunities.

Impacts achieved and pending challenges

Bogotá has positioned itself as a benchmark in caregiving policies, with a District System that is a pioneer in Latin America because of its gender approach. The success of this model has crossed borders: at the national level, cities such as Cúcuta (Norte de Santander) are already exploring its implementation. At the regional level, representatives from countries such as Brazil have visited the Manzanas del Cuidado to replicate this program, adapting it to their local realities.

However, while the District Care System and the Manzanas del Cuidado are trailblazers, their implementation continues to face obstacles. The main limitations noted by both officials and beneficiaries are operational and cultural, grouped into four main points. These are expansion to rural areas; measurement of the real impact on the redistribution of care; the financial viability of the system; and the economic independence of caregivers.

To address the scalability challenge in rural areas, the Care Buses strategy has been implemented, aiming to reach the most remote rural areas of Bogotá. Nataly Sánchez, Coordinator of the Juan Rey Manzana del Cuidado, explains: “They are a mobile version of the Manzanas del Cuidado—buses equipped to provide training and support services to women and their families.”

However, Nataly cautions that while mobile infrastructure solves physical access, more complex questions remain:

“Rural areas have unique characteristics due to their community dynamics. It’s crucial to recognize these differences. These are rural women. We must engage with them and ask, how do they understand caregiving? What does it mean to them?… Each community understands caregiving differently.”

The core challenge in the redistribution of care, both in the domestic and public spheres, revolves around assessing how much the distribution and dynamics of invisible work have evolved: from daily food preparation and wardrobe maintenance to household cleaning, ongoing childcare, care for the elderly, and specialized support for people with disabilities.

Among the District Care System officials, a fundamental question persists, as Diana Munar, a trainer for the Manzanas del Cuidado, puts it: “Have we truly achieved a fair and equitable distribution of these caregiving burdens, both within homes and across society?” Diana adds:

“The current challenge is getting women caregivers to redistribute caregiving. We’ve identified that, to attend our spaces, many get up early. They come to the center only after completing all their household chores. The real challenge is getting them to let go of those burdens, although we recognize the difficulty, as this is deeply rooted in our culture.”

To achieve the necessary cultural and social changes, they have implemented pedagogical strategies such as “A Cuidar se Aprende” (Learning to Care) and the “Men in Care” School. As long as men continue to identify caregiving solely as a woman’s job, it will not be possible to advance the equitable redistribution of tasks or the recognition of unpaid care work. These initiatives, groundbreaking in Bogotá, seek to radically transform the traditional concept of caregiving. Nataly says:

“The idea is for them to be able to let go and unburden themselves of domestic duties. They can come here to our activities, but if everything remains the same when they return home, we’re not achieving real change. We need them to learn to delegate and for men to become more involved in household chores, developing a better understanding of these responsibilities.

The long-term sustainability of the District Care System faces two fundamental challenges: first, maintaining the political will to ensure its continuity; and second, reducing the economic barriers affecting women caregivers. Sharon expresses this concern:

“We seek to ensure that the Care System does not weaken… This began with the previous administration. It was positioned, strengthened, and this new administration came into being—[the system] continues to hold up. However, we need to work hard on this will to continue, because the problems faced by women caregivers are still present. The economic barrier associated with care work must be reduced.”