Conversation groups for men to mitigate the damage caused by rigid gender norms are used to confront gender inequity in this story about Program H, which emerged in Brazil and has been replicated around the world. Journalist Soledad Bavio tells the story in this piece created with a Gender Equity Reporting Grant from the Latin American Solutions Journalism Fund, an initiative of El Colectivo 506, thanks to a donation from the Solutions Journalism Network and the Hewlett Foundation. It was published by elDiarioAR on May 1, 2025, and is adapted and translated here by El Colectivo 506 for co-publication. Please note that the English version has been edited for clarity and regional context.

“I try to laugh about it, hiding the tears in my eyes, because boys don’t cry.”

The Cure sang this in 1979 in an attempt to defy social pressure, giving voice to the suffering of a man who’s being asked to live behind an emotional and senseless shield, leaving his personal feelings behind.

However, another perspective is possible: a way of understanding men that understands inequalities, underpins the struggle of feminism, and that uncovers the serious consequences for both women and men subjected to rigid gender norms.

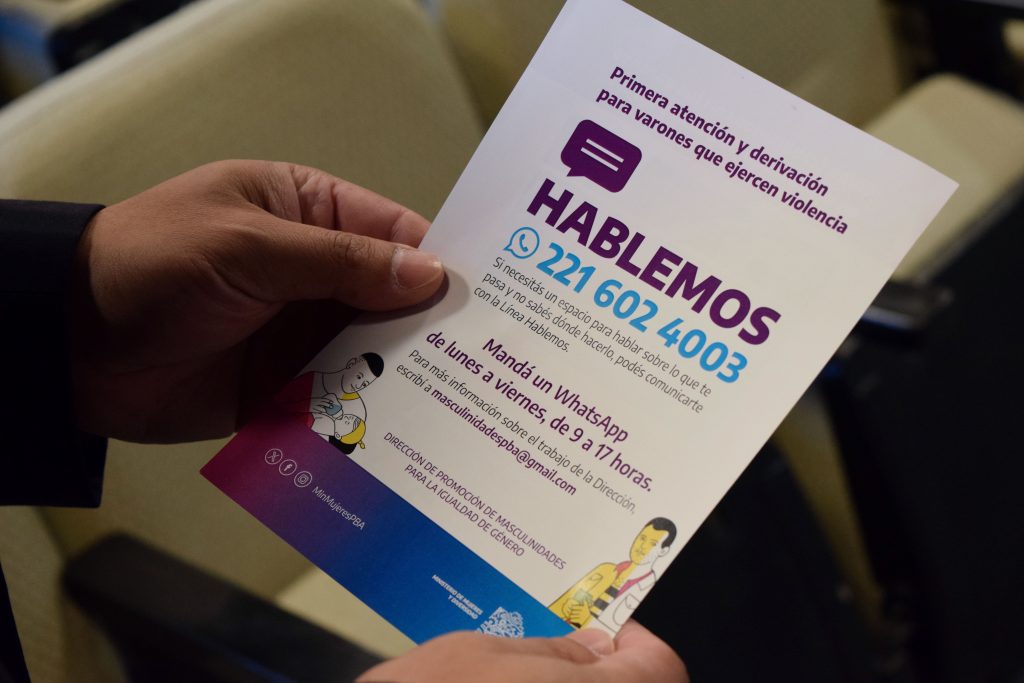

“It is important to look at men, not only as ‘healthy children of patriarchy’ or when they commit violence, but also when they commit suicide three times more often—or when they commit three times more traffic accidents for the same number of kilometers traveled than the rest of the drivers,” says Nicolás Pontaquarto, a specialist at Argentina’s Institute of Masculinities and Social Change. This civil association works throughout the country, advocating the design, implementation, promotion, and improvement of public policy.

“The masculinities approach involves getting specific,” he adds. “It’s about understanding men affected by gender [norms], and how this has affected their lives.”

For Pontaquarto, “privilege is structural. It’s about the role and position of men in a sex-gender system that places [maleness] as the most valued hegemonic normative identity, with more prerogative, more freedoms. That is undeniable—and discussing such a systemic rule individually [one man versus one woman] does not make any sense. Patriarchy and capitalism generate privilege for most men in relation to most women, in general terms. In conversations with men, this lesson opens a window to talk about the costs of suffering and pain.”

However, gaining this perspective doesn’t have any impact on its own. The knowledge needs to be used to create structural change in the face of discrimination and violence based on the culture of privilege. After all, violence against women is a manifestation of lack of equity and a violation of human rights. In 2021, at least 4,473 women were victims of femicide or feminicide in 29 countries and territories in our region, according to official data reported by the countries to the Gender Equality Observatory of Latin America and the Caribbean. This represents at least 12 gender-based violent deaths of women every day in the region.

The Global Gender Gap Index, which records data from more than 140 countries, concluded in 2024 that “the scale and speed of progress are profoundly insufficient to achieve gender equality by 2030. The reluctance to adopt gender parity as a condition is costing women and girls their future.”

Meanwhile, youth violence costs the lives of thousands in the Americas. Homicides are one of the leading causes of death among youth, especially men and boys aged 15 to 24. Men are victims, and men are perpetrators.

Reshaping the path

From young people less tolerant of violence in Latin America, to men who participate more equitably in household responsibilities in India. What do these men with such dissimilar idiosyncrasies and geographies have in common? They all challenged gender norms—and they did it through these new ways of thinking.

In Brazil in 2002, through non-governmental organizations such as the Promundo Institute, ECOS, the Papai Institute and Salud y Género, Program H was created. This initiative sought to help young men in Latin America address the gender norms associated with hegemonic masculinity. Since that time, it has been replicated in more than 30 countries and has become a globally recognized program, named as a best practice by the World Bank and the World Health Organization.

Program H was developed using research with low-income youth in Brazil that challenged traditional notions of what it meant to be male. The research identified three common factors among those who expressed support for gender equality: belonging to groups of men with equitable attitudes; having had negative experiences linked to traditional models of masculinity, such as violence or parental abandonment; or having role models that challenged gender stereotypes.

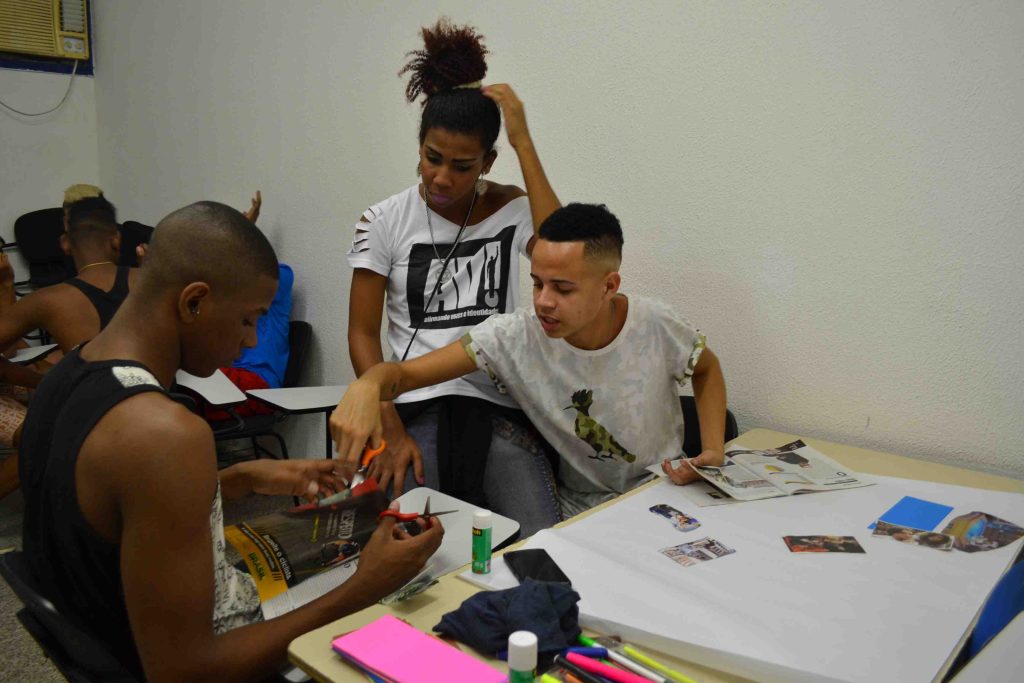

Based on the research, Program H developed group educational activities designed for young men, and facilitated by men who act as models of gender equality. Guided by a manual, these group facilitators include role plays, debates, and interactive exercises to reflect on male socialization, its effects and the benefits of changing certain behaviors. Topics cover sexual and reproductive health, violence prevention, parenting, family care and HIV/AIDS.

“The existence of initiatives such as Program H was key to Brazil’s pioneering character in this field,” says Bruna de Oliveira Martins, Anthropology and Human Rights consultant at the Promundo Institute. The institute promotes gender equality and violence prevention, with a focus on the participation of men and women in the transformation of masculinities. “While it’s being updated, it continues to be innovative and addresses issues that, until today, have been little debated—or not debated at all—in the male universe. In recent years, one of the main advances has been the constant updating that Promundo has promoted in debates about masculinity, incorporating perspectives on trans masculinities, homoaffective masculinities, black masculinities, and masculinities in traditional communities, among others.”

He adds that “Brazil, in terms of public policies, is quite unique and innovative. Proof of this is the existence of the National Policy for Comprehensive Care of Men’s Health (PNAISH), which recognizes that machismo and other patterns of risky male behavior not only affect women and other gender expressions, but also men themselves.”

The impact of Program H is measured by the positive changes in young men’s attitudes toward gender norms, as well as related behavioral changes. In 2021, the available evidence was compiled in a report which evaluated almost two decades of implementation. In most studies, young people showed more equitable attitudes after the intervention; others indicated a decrease in the acceptance or perpetration of intimate partner violence, and improvements were observed in regards to sexual and reproductive Health. The Gender Equality Scale for Men (GEM) was used to assess the impact of the program.

Cultural and contextual adaptability

Program H has a great strength: its adaptability. This was the starting point for the formulation of another identical program called Program M, for women, based on research and designed based on the experiences of young women in low-income communities in Brazil and Mexico.

However, according to the evaluation cited above, the long-term sustainability of these programs “depends on the buy-in of local non-governmental organizations and key stakeholders. In some settings, conservative political leaders have actively opposed the program as it includes frank discussions about sexuality, sexual diversity, gender equality, and the questioning of traditional ideas of masculinity.”

Building on the success of Program H, Brazil, Chile, India, and Rwanda joined together to carry out the Multicountry Project that has confirmed the effectiveness and efficiency of group education.

The project was implemented in collaboration with MenEngage, a global network of non-governmental organizations working to engage men and boys. Hernando Muñoz Sanchez, the regional coordinator for MenEngage Latin America, says that “when I do training on the topic of masculinities, I use a key phrase: ‘raise awareness’ about our role in social transformation. In the methodology with men, we must first work from reason.”

“Through this work, men can take responsibility for themselves, challenge regressive gender norms, and emerge as critical allies in the fight for gender justice,” he says. “When men are moved to cultivate mutual respect within families, new models of masculinity emerge and the rights of children, especially girls, are defended.”

“Through this work, men can take accountability for themselves, challenge regressive gender norms and emerge as critical allies in the fight for gender justice,” says Anwesha Chatterjee, deputy director of Sahayog India, which has formed more than 150 men’s groups in Uttar Pradesh, with the active participation of 4000 men. “This engagement, first and foremost, needs to impact men at an individual and family level, transforming the relationships that they have with their spouses and their children, based on the values of mutual respect, and care. When men are moved to cultivate mutual respect within families, newer models of masculinity emerge, and the rights of children, especially girls are upheld, thus positively impacting the journey towards achieving gender justice.”

Pedagogy, reflection and peer groups, as a global response

Considering that the key problems in India are patriarchal roles and rigid ideas of masculinity; the high rates and levels of gender violence; and the fact that the country’s primary institutions continue to be patriarchal, Sahayog focuses its efforts on a “network-based model.”

By working through community groups and leaders, Chatterjee says, the program supports “men who want to experiment with new behaviors, and benefit from a peer support group.” These men then “derive benefits from those changes through improved relationships at the family level; changing understanding of gender power relations and male privilege in addition to demonstrated societal-level changes in gender attitudes.”

Muñoz Sánchez, from Colombia, describes efforts in his country along similar lines: “We trying to do pedagogical work, to raise awareness so that what happened in childhood is not repeated. I think there is a little hope… when [participants] commit to two or three very simple things to transform.”

For his part, Pontaquarto in Argentina states that questioning what maleness means “generates reactions. There is resistance, and we must understand that it is a process. We are in a context trying to repair some wounds and [reestablishing] dialogue that was broken.”

de Oliveira Martins, from Brazil, says that these steps are absolutely essential in addressing gender violence: “Without the participation of men, and without addressing their masculinities in the discussion on gender equality and the reduction of violence, it is not possible to work on either the cause or the prevention of the problem. If only women and other people affected by machismo are involved in the discussions, no structural change occurs.”

Although the experience of Program H shows that the young people involved find it a fundamental resource, the main challenge is to get them to the table in the first place by signing them up to one of the groups. Since the target population, young men between 20 and 24 years old, tend to prioritize work or vocational training, program implementers have found that including incentives such as sports or vocational training have improved recruitment and retention.

Evaluations also showed the need to include deeper work on sexual diversity and sexual rights, given that homophobic attitudes based on rigid ideas persist among many participants. Program leaders have therefore involved youth participants directly in the design and implementation of these programs.

Facing resistance within and without

Like any interventional and transformative process, the program faces tough battles. Challenges noted in program reports include participant retention; the active involvement of communities; implementing monitoring systems; and integrating the program into partner institutions to ensure sustainability.

de Oliveira Martins states that “in conservative times, the promotion of initiatives that question rigid gender norms is a challenge. Claiming that gender is a social construction is not always immediately accepted. This is not a war of the sexes or the destruction of the family, as some groups claim.”

“I think we are facing a difficult time to do this work, but it is worth continuing to sow seeds,” argues Muñoz Sanchez. “There are rights that not only come from the North but are in the global South and are part of a complex situation.”

“Resistance can be an obstacle that speaks of a discomfort processed in a very masculine way, from a very masculine place: getting angry, becoming aggressive, responding with violence,” says Pontaquarto. “We need to understand the discomfort itself so as to avoid caricature, and think about how uncertainty plays out for those of us who have also been raised amidst the certainty of having a familiar script or model to follow.”

India is not far behind, says Sayahog: “With the rise of right-wing… and authoritarian governments, a new kind of aggressive masculinity is on the rise. Control and violence [are directed] not only towards women, but also towards other men from minority communities, such as Muslim, Dalit and Adivasi men.”

Plans for the future, evidence-based

In India, the program will continue to pursue its work, believing that “Not all men in society agree to violent patriarchal control of women. Some of these men can be encouraged to get associated with initiatives aimed towards gender equality at the family and community level,” says Sayahog.

Múñoz Sánchez, of MenEngage Latin America states that “we must continue clarifying and fighting to be able to establish other paths and other perspectives to stop doing what we have been doing. That is raising awareness in men.”

And de Oliveira Martins, of Promundo, says that “Program H is undergoing a rigorous update that seeks to maintain the same pioneering character that it had when the methodology was launched. Like the other Promundo methodologies, it is quite flexible and, at the same time, has the necessary rigor to adapt to different contexts… gender issues impact the daily lives of all people, so knowing how to address these issues in a stimulating way is key to the continuity of work, even in environments where there is no prior interest in the study of masculinities.”

Dissimilar experiences, distant latitudes, diverse geographies and idiosyncrasies—from all of these, program leaders point out similar goals. Build healthier networks, more equitable and less violent countries. So far, their work seems to highlight a possible path towards reshaping an oppressive system—towards daring to express that inner struggle. Towards eradicating the collective thinking that “boys don’t cry.”