Sofía is angry about the rampant misinformation about HIV that, as she looks back over her life, has made her feel so alone. (Read more about her story in part 1 of our series.) But the story of this 27-year-old and her HIV treatment also shows the power of interdisciplinary treatment—the power that a group of professionals from different fields, working together at a special HIV clinic at a public hospital, can have on the mental and physical health of a person with HIV. Her experience is a reminder that, while the prevention and treatment of HIV continues to face significant challenges around the world, the past four decades have also seen massive advances.

The first official reporting about what would come to be known as AIDS, or acquired immune deficiency syndrome, took place in the United States in 1981, when Pneumocystis pneumonia was reported in previously healthy, gay men in Los Angeles, California, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC). The following year, the CDC used the term AIDS for the first time, as the virus that causes the disease—human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV—accelerated its spread through populations around the world.

The virus is spread through contact with some bodily fluids of a person with HIV, and can be transferred through unprotected sex, the sharing of injection drug equipment, blood transfusions, or childbirth. This last form of transmission, which is what Sofía experienced, is known as vertical transmission.

A total of 85.6 million people have been infected by HIV since the start of the epidemic; at the end of 2022, 39 million people were living with HIV, according to the World Health Organization. HIV-AIDS has claimed 40.4 million lives, and the life expectancy for someone with the disease, without treatment, is approximately three years. However, in much of the developed world, and in developing countries with robust public health infrastructure such as Costa Rica, the terrifying early years of the epidemic seem safely in the past. While Costa Rica’s overall HIV case numbers have increased in recent years—a topic we will explore in other stories this month—the development of antiretroviral therapy (ART), which was first approved for Costa Rica in 1997, changed the game.

HIV attacks the immune system’s infection-fighting CD4 cells; ART essentially prevents the virus from making copies of itself, thus allowing CD4 levels to increase once more. While the body cannot get rid of HIV, people with the virus who receive medication can reduce the amount of HIV in their blood, or their viral load, to low levels. They can even reach levels that are undetectable by standard lab equipment. With an undetectable viral load, people with HIV will not even transmit the virus to their partners through sex. And with proper treatment, they will never develop AIDS.

But these successes require early detection, followed by lifelong access to medication, and strict adherence to treatment. All of this requires funding, staffing, and integral support for people with HIV, including mental health care. That’s why the tremendous leaps in HIV treatment have been denied to so much of the world’s population. And that’s also why mental health care, often relegated to secondary status in health care systems, must be at the forefront of HIV treatment.

“The biological part, the physical part, is very simple today, thank God,” says Costa Rican palliative care specialist Dr. David Reyna, who also holds a master’s degree in HIV studies and is the founder of the Care with Love Foundation. He powers the foundation through his own donated time to offer lectures and resources on HIV and palliative care, with the ultimate goal of raising funds to build a hospice. “There’s highly effective medical treatment with very few side effects that really takes them to an undetectable viral load very quickly, through which they can have a long life with excellent quality of life and even have a family without infecting the other person… but the psychosocial part is more difficult, starting with the stigma that they all face… even from health personnel.”

David Reyna is part of the initiative at the heart of Costa Rica’s response to the multifaceted challenge of providing integral HIV treatment by creating interdisciplinary HIV clinics at its major hospitals. He is a doctor at the HIV clinic at the Hospital México in western San José; there are seven in Costa Rica, all at hospitals within the GAM (the Greater Metropolitan Area in the Central Valley), with six additional “peripheral clinics” in more rural areas.

Starting with the first clinic at the heart of downtown San José, the Hospital San Juan de Dios, which opened in 1993, the clinics unite professionals in HIV treatment, psychology, psychiatry, nutrition and other around the treatment of people with HIV. When antiretroviral therapy was approved by Costa Rica’s Social Security System (CCSS or Caja) in 1997, the clinics were restructured around the corresponding treatment plans.

“It’s a very complete team with which we can address [patients] from different areas of life,” says David Reyna. “What’s missing is decentralizing it a bit… patients from Upala, Liberia, the Southern Zone, have to be transferred whether they have money or not.”

Sofía’s story, while rife with tragedy and struggle, also demonstrates just how powerful these interdisciplinary teams can be.

Sofía says that her family didn’t know how her mother had died; therefore, it took a long time and a lot of pain before she was even diagnosed. She started feeling sick when she was about 14. Despite experiencing diarrhea for what she remembers as a full year, she never told her family. Her relatives finally sought attention for Sofía after she collapsed on the way home from high school one day. Because she was not sexually active, she says that it took multiple rounds of medical attention and tests until the Caja consented to including an HIV test among her screenings, and she was finally diagnosed.

She says she has never been one to talk openly about what she feels. This increased once she was diagnosed with HIV.

“At 15, I was forced to grow up fast,” she said. “In a way, I didn’t enjoy my youth because I had this diagnosis and I thought I was going to die at any time. I was just waiting for my time to come.”

Just like the other interviewees for this story, she says she was not given clear information about the implications of her diagnosis.

“There wasn’t much information about what HIV was, and what it meant to have the virus… after that, I didn’t talk to anyone. I had no friends. I stayed in my world, in a box, basically. I pulled away from the outer world and even from my family.”

Her family did not ease her isolation.

“To a certain degree, my family didn’t educate themselves, either,” she says. “Even to this day they need to do a bit more. They gave me a separate plate, everything separate… They acted as if they weren’t afraid, but they were. One thing is what you say and another is what you do. You suffer discrimination from your own family.”

When it came to her treatment, this combination of fatalism and isolation meant that Sofía did not adhere. Even though her medication regimen brought her viral load to undetectable levels, she then stopped taking her medications and lied to her doctors about it—again and again. The staff of the interdisciplinary clinic at the Calderón Guardia Hospital in east-central San José, particularly her main doctor and the psychologist, knew that she wasn’t taking the medication, because her viral load increased and her CD4, a white blood cell level that is critical in monitoring HIV patients, were decreasing. They tried to get her to admit that she was not taking her medication and to talk about how she was feeling, she refused to admit that anything was wrong.

Even during this brief interview, even across the table in this office at the HIV home, the toughness and strength of this woman is almost palpable. It’s easy to imagine a scenario in which a stubborn young Sofía would have continued to succeed in defying and deceiving her health care staff, slipping through the cracks as her health continued to worsen. It’s clear that such a fate could only have been averted through precisely the kind of concerted intervention she then describes.

On one visit to the hospital, a HIV clinic nurse took Sofía to a private office. “My doctor arrived, and then the psychologist, and then the other nurse, and they started to talk to me,” she remembers. “They said, ‘Sofía, we know perfectly well that you’re not taking your medication.’ I opened up and started to cry. I had never [done that before]. I always had it bottled up. I’d felt that I had no right to cry, that I had no right to a lot of things. I had no right to be alive.”

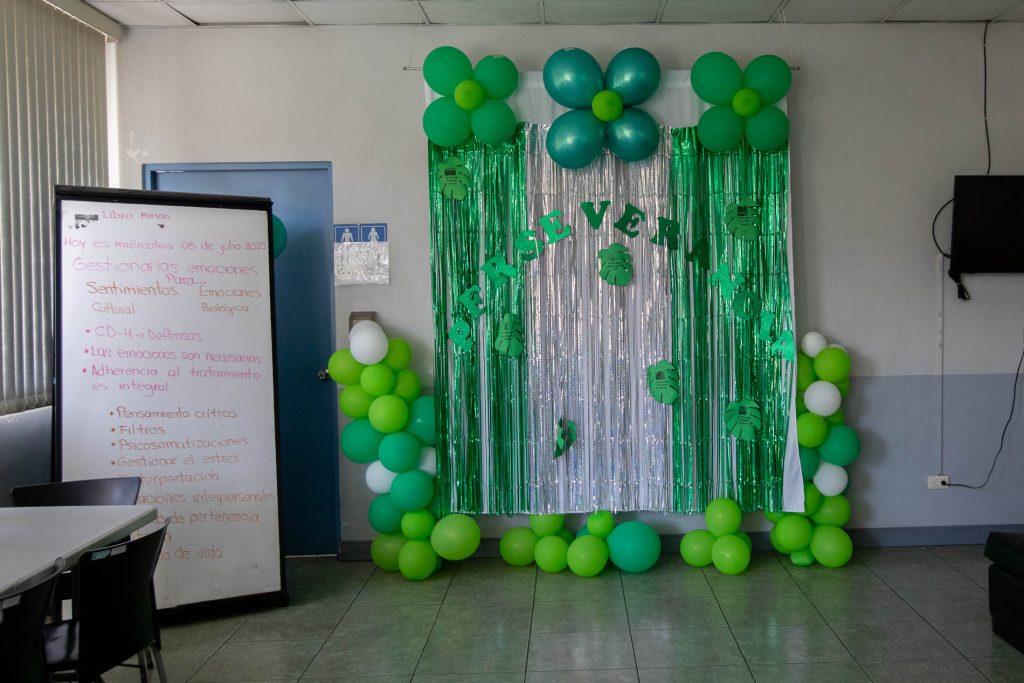

During this conversation, Sofía told the team about problems she was having at home. They recommended that she consider moving to the VIH Hogar Nuestra Señora de la Esperanza. This home for people with HIV in Cartago is a private, nonprofit facility founded more than 20 years ago that provides everything from treatment and physical therapy to psychological support and vocational training for up to 30 beneficiaries.

Sofía said yes—and while she remembers with a laugh that she instantly regretted the decision, she stuck with it nonetheless, broke the news to her family, and moved to Cartago. There, the interdisciplinary support she had been receiving at the public hospital leaped to the next level, with daily psychological support and intensive education about HIV. She says this is what allowed her to get serious about treatment and envision a healthy life ahead.

However, she says while the home is an oasis, misinformation and stigma continue to surround her outside in places like that Caja reception desk and the dentist office with triple-gloved staff. The success of the Caja’s interdisciplinary clinics has not gone hand-in-hand with broader education about HIV within the general population, or even within public health institutions.

What are the mental health consequences for people with HIV? And how can that affect their treatment and life expectancy?

For that, we’ll turn to someone sitting across from Sofía at the table today: her fellow resident of the VIH Hogar Nuestra Señora de la Esperanza. We’ll hear from Miguel.

This longform piece, published in four parts, was supported by the Internews Health Journalism Network. Learn more about the Nuestra Señora de la Esperanza HIV Home on their Facebook page or donate via SINPE Móvil at 8507-7676. Learn more about Dr. David Reyna’s Care with Love Foundation here.

*Sofía’s real name has been withheld at her request, to protect her privacy and in consideration of the discrimination that is faced by people with HIV in Costa Rica.