Second in a four-part series on education and the pandemic in Costa Rica, inspired by a 2006 series by our co-founders that followed three second-graders through their school days in three very different Central Valley schools. Read Part One here.

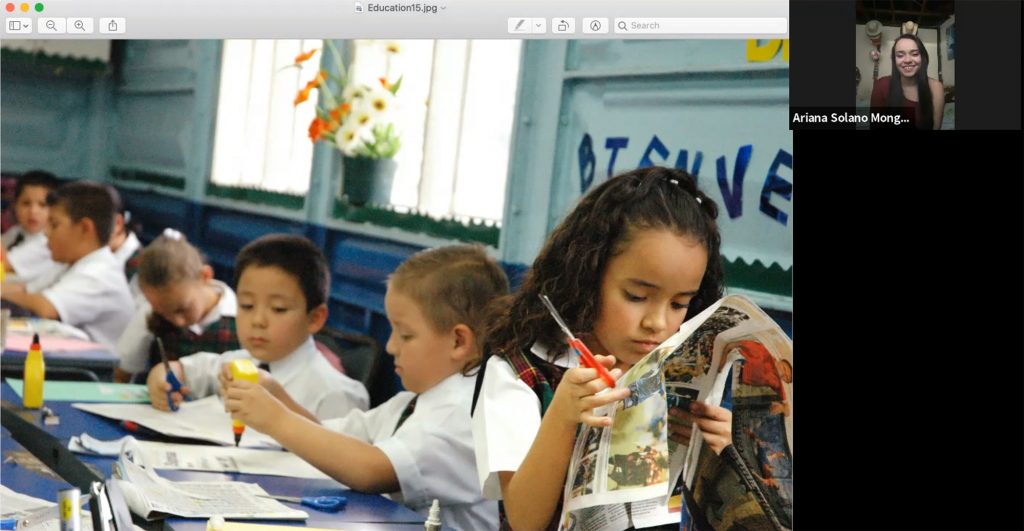

“Awwww,” says Ariana Solano Monge, 22. “Look at that!” We smile together as we look at a photo of her in her second-grade classroom in downtown San José. We’re sitting on a Zoom call, having just reconnected after 15 years. Her curls, so pronounced in 2006, are now flat-ironed straight; she seems very practical and organized; she adores her pets, introducing us when we visit for photographs to her ornery dog and beloved cat.

She still lives on the same street in Cinco Esquinas de Tibás where she grew up. The narrow street has no through traffic because it is a cul-de-sac, ending with a devotional statue and a view to the north; it is calm and quiet, despite its location in a crowded urban area just a few minutes’ drive north of the school that Ariana and all her siblings attended, the Escuela Buenaventura Corrales near Parque Morazán. Like many Costa Ricans, Ariana lives with her siblings, parents and grandparents within a few doors of each other: Her father, Alberto Solano, is an industrial supervisor, and her mother, Grace Monge, worked at the National Insurance Institute (INS) at the time of our 2006 interview but now is at home and helps care for Ariana’s 10-year-old nephew, who attends the Escuela Buenaventura Corrales as well.

Arianna’s life—absurdly reduced to a few minutes on Zoom the way it inevitably is when a reporter asks a woman in her 20s, “So, what have you been up to since second grade?”—seems to trace a cheerful arc. She has the fondest of memories of the place popularly known as the Escuela Metálica; it’s an unusual public school because it has few kids living in its neighborhood and therefore has become a bit of a magnet, drawing students whose families can afford to pay for transportation. She went on to a parochial high school in Heredia, un colegio subvencionado, meaning that the Costa Rican government underwrites part of its costs so that its fees are more accessible. Throughout her school career, she danced as an extracurricular, and even worked professionally with a dance troupe after graduation for a time.

Looking back, the one disappointment Ariana expresses with her education is the fact that she wasn’t able to prepare for what she calls her “dream career” as a veterinarian. It’s not an unusual story in Costa Rica, where public university exams determine not only whether a student can enter a given institution, but also which majors he or she is allowed to study; majors such as medicine require the highest results, whereas majors such as teaching and journalism, ahem, can be studied by lower scorers. Ariana took the text three times for the National University, or UNA, but kept missing the cutoff for veterinary science by 10 points despite the fact that she had studied for and achieved a special technical degree in the field to prepare for the specialty. While her parents had paid for the slightly higher school fees of the Escuela Buenaventura Corrales and then a parochial high school, the fees of a private university were out of her reach, and she didn’t want to take out a loan.

She ended up in a related field, biology, that required a slightly lower score, but after a couple of years, she decided she didn’t want to continue.

“I saw my classmates with a lot of passion for being there,” she remembers. “It wasn’t for me, and no matter how hard I worked, it wasn’t going to be what I wanted.”

She left university and now works at the call center Concentrix across town, although she does remote work during the pandemic. This job has whetted a desire to study business administration. Now more than ever, during the pandemic, it’s a practical option, she says, giving the impression of a woman with her feet squarely on the ground.

She talked about her own school experience versus that of her nephew, 10, who now walks the same halls she once did at the Escuela Buenaventura Corrales, and has many of the same teachers. (Her second-grade teacher, Guiselle Quirós, is still teaching second grade at the school.) When Arianna reflects now on the differences between her schooling and her nephews, one change that makes her sad is the advent of technology.

“I think that technology has played a positive but also a negative role in education,” she says. “I didn’t hear of cell phones until around fifth grade, when a few friends started having them… Now you see [the kids] and they’re super dependent on it, always wanting to have technology around them. A tablet, a computer, a phone.”

She reminisces about little details she remembers: the chalk her teacher used to write with back then, and the way her family kept a bag of advertisements and other materials from which Ariana and her siblings could cut out pictures for school assignments. I mention that on the day I spent with her in second grade, I watched her do just what she’s remembering: cut out pictures from newspapers and use them to make a collage as one of Guiselle’s lessons. I even share my screen to show Ariana the photo. I tell her how, having just spent time in lower-income schools, I was impressed by the newspapers on hand for the kids to use, the glue, the space to cut and create.

“I feel that we’ve lost something there,” she says, looking at the photo. “It’s not the fault of the education system, either, but I think one point in favor of my generation is that we came along at a point where technology was used, but it was not yet indispensable.”

Technology and schools

You know what? I know what she means. The day I reported on Ariana’s second-grade life, I had a blue Nokia in my pocket, one of the phones that in Costa Rica are lovingly recalled as a tuco, a slab of wood, a Nokia 3110 (a prized possession and rare among my international friends because, at the time, one still needed a Costa Rican sponsor in order to get a cell phone line). Technology was still rare enough on Costa Rican streets, and my fear of theft high enough, that I tried not to use it on the street. Today in Costa Rica, of course, people from all walks of life might whip out a laptop or a drone or at least a giant smartphone in any setting at all without thinking twice.

At this pace of dizzying change, I’ve felt resistant to too much technology for kids; fairly uninterested in tech in the classroom for my daughter; and glad that I didn’t have to deal with all of this when I myself was a classroom teacher, when my own decidedly unintelligent phone stayed in my desk, and students having their own phones in the classroom was barely a dot on the horizon.

In a way, Ariana’s lament makes her sound much older than she is, but that’s quite common in Costa Rica because of how quickly things have changed over the past 20, 50, 100 years: the growth in its population, the head-spinning alterations to San José. Then again, she’s speaking to something that crosses borders. When it comes to technology, most any person in Ariana’s generation—at least, in an urban area, with schools that are embracing change—has grown up seeing a drastic change in the way they were educated versus their children or young nieces, nephews and neighbors.

At the same time, of course, our shared concern about technology in education comes from a place of privilege. It is perhaps not surprising that, of the three children from our 2006 report on educational inequality, Ariana was the easiest to find and interview: the quickest to respond on Messenger, to move with us to WhatsApp, to accept and attend a Zoom invitation. Her school is similarly easy to navigate online. Alone among the three schools we reported on in our 2006 series, the Buenaventura Corrales has a Facebook page that links to an email account, easily accessible phone numbers, a website, and even a blog.

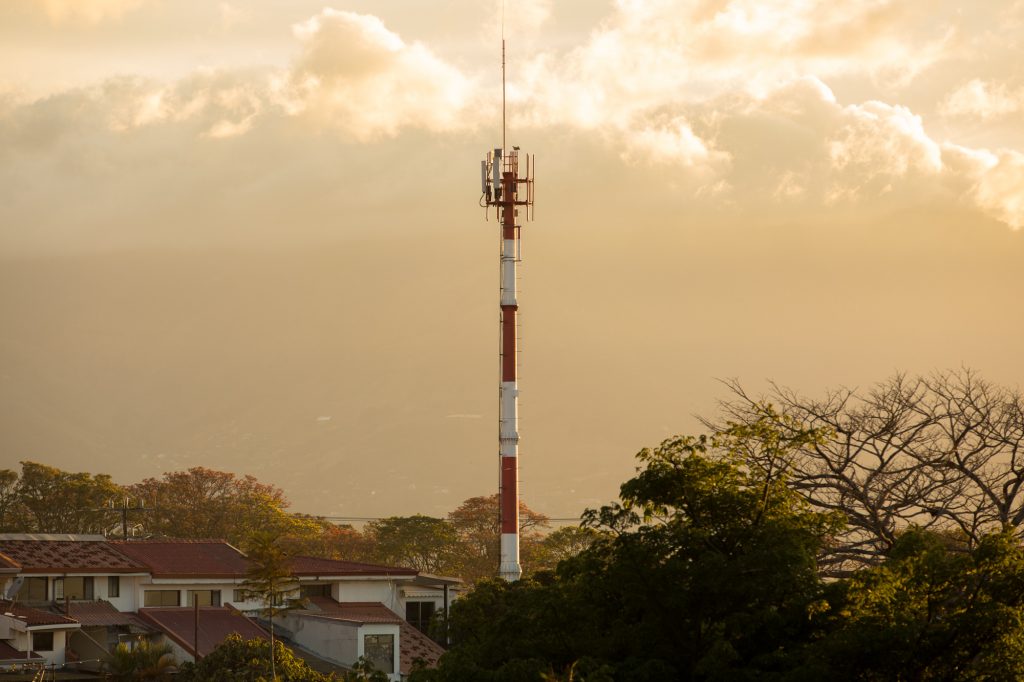

This reflects a number of aspects of Costa Rica’s digital divide. First, connectivity for schools: Paula Villalta, the Vice-Minister for Institutional Planning and Regional Coordination, told me that 87% of the country’s schools have “some type of internet connection…but most of those are of low quality.” (This reflects what teachers have told us in interviews this month about connections that are patchy, unreliable, or only allow a few teachers to be online at a time, a significant problem at even a little school.)

Second, it speaks to connectivity for homes, because if a school’s parents aren’t connected at home, why have a website and a blog? While home connectivity rates are about 80% for “rich homes” and 60% overall in urban areas in Costa Rica, they drop to 40% in low-income or rural areas, and even less in isolated rural areas, says Isabel Román, who leads the State of Education program at the State of the Nation think-tank. When one takes a cell phone connection out of these numbers, they drop even further. Altogether, she estimates that 418,000 of the country’s 1.1 million students “were not in good conditions to connect” before the pandemic.

And these are just connectivity figures. They don’t even take into account the knowhow and equipment needed for teachers to make use of technology: one recent but pre-pandemic study showed that a whopping 67% of teachers did not use technology for their own professional development, says Román. And while the Omar Dengo Foundation and other nonprofit entities have provided thousands of Costa Rican schools with computers and training, those tend to center on computer labs, not mobile technology that enters mainstream classrooms or students’ homes.

None of this is new information. But the pandemic, so quick to detonate explosions in so many aspects of our lives, blew up how many of us see technology and education. At least, it’s done so for me. In pulling on this thread of this month’s issue—in exploring the stories of Ariana Solano, Steven Montenegro and Greivin Cruz, and the communities they come from—I’ve come to realize something I didn’t before. Technology in education is not just about teachers using tech in their classrooms. As Ariana says, it’s everywhere. It’s about the way an education ministry tracks its kids… or doesn’t. How a principal knows how many bags of rice to distribute in a pandemic… or doesn’t. How a teacher keeps in touch with her students at one of the worst times in their lives… or how she loses them.

It’s not just one aspect of the pandemic. It’s at the heart of every conversation I have as I try to walk in those 15-year-old footsteps. The more you talk about education during the pandemic, the more you start to realize that the biggest tool to create equality in 2021 is something that can’t be seen.

The good, the bad, and the disconnected

One of our goals this month was to examine how the Escuela Buenaventura Corrales, where Ariana went to school; Greivin’s Escuela Finca La Caja, now the Escuela La Carpio, in a large, low-income, binational community on the western side of the city; and Steven’s Escuela Llano Grande Pacayas, in the Cartago countryside, have fared since 2006.

The short answer is: better. Before the pandemic, things were improving. The educational indicators that graphed and sliced and diced the experiences of the three children I followed in 2006 have improved—subtly, in most cases, but unmistakably, and nearly across the board. Look further back at the arc of access to quality education in Costa Rica, and you can see that this country, renowned for its investment in human resources, has made a vertiginous leap in recent decades and is now experiencing the growing pains of moving the needle at the top of the curve.

In 2006, there were so many factors to look at in terms of inequality. The differences in infrastructure that allowed Ariana to cut out those pictures in a large, sunny classroom, while Greivin struggled to hear in a cramped space. The number of students in a school, which led to multiple school shifts for Greivin and Steven, thereby slashing their daily instructional time. The physical distances that threatened to keep both Greivin and Steven from attending high school, when they would have to pay to get to and from a far-away institution rather than walking to their elementary schools. The cost of uniforms and other fees related to in-person schooling, which, in the case of Steven’s rural family, added up to $400 a month for 12 children.

Over the past 15 years, massive nationwide changes that have moved forward—in fits and starts, certainly, but forward. The push towards a 200-day school year that has gradually increased instructional time, such a differentiating factor in our 2006 series. The push towards spending 8% of GDP on education that have contributed to infrastructure improvements such as those that are visible today at the schools Greivin and Steven attended. Massive nationwide curricular reforms. While the most recent installment of State of the Education reports that Isabel Román coordinates signal urgent needs for improvement in long-standing problem areas such as the digitalization of Education Ministry processes, coordination of teacher preparation programs and hiring requirements, the 15-year view, like Ariana’s, is a positive one.

Then March 2020 arrived, and suddenly—for a time, at least—all those other factors disappeared. Suddenly, all that mattered was whether or not students could connect; what to do with them if they could; and what to do with them if they couldn’t.

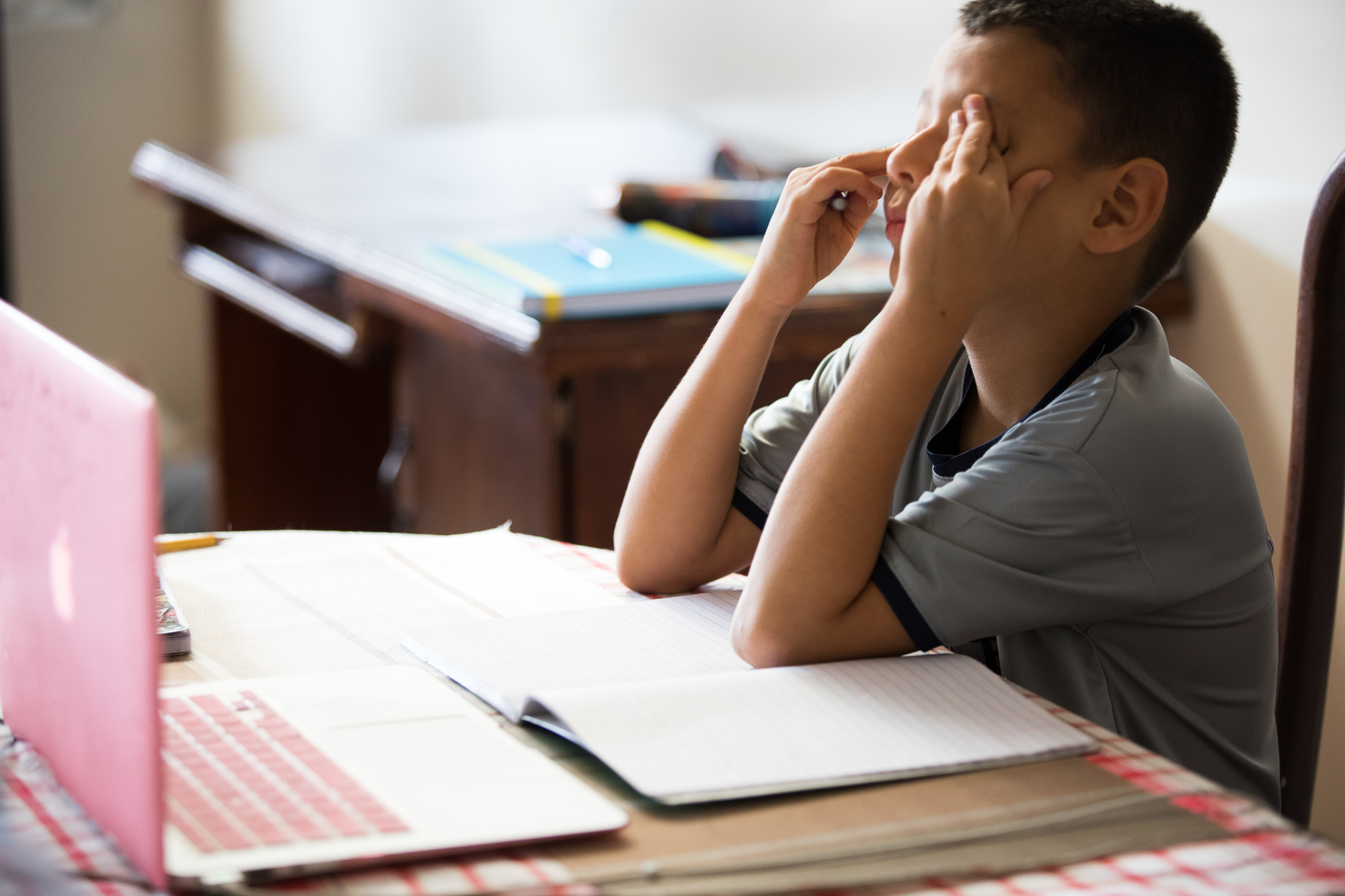

The Education Ministry emitted “guías de trabajo autónomos,” curricular workbooks that could be used by families at home. It created hundreds of thousands of email and Microsoft Teams accounts for students and teachers alike, and undertook a massive effort to train its teachers on Teams. In urban areas, kids like Ariana’s 10-year-old nephew began attending virtual classes and working on the autonomous guides at home.

With connectivity even in well-to-do families at only 80%, according to Román’s data, not even a school like the Buenaventura Corrales could count on all kids to connect reliably; those who couldn’t might connect with the teacher over WhatsApp, using a parent’s phone. At rural schools such as Llano Grande and low-income urban schools such as La Carpio, WhatsApp was a best-case scenario: “some students had connectivity and a few teachers managed to give them individual classes on WhatsApp or Zoom, but those were minimal cases,” says La Carpio school psychologist Rosibeth Alvarado.

For everyone else, even an attempt at remote schooling was unthinkable. In crowded shantytowns like Greivin’s La Carpio and rural towns like Steven’s Llano Grande de Pacayas, schools printed out the guides for parents to pick up once a month at the school, work on at home, and return to school in order for bags full of food that would keep families going as long as school lunchrooms remained closed.

Vice-Minister Villalta expresses satisfaction that by the end of 2020, 96.1% of students remained in the school system, although she admits that “remain” was a lot harder to define in 2020 than in previous years: really, it means that the students had not left the country or completely lost touch with the their teachers. Looking back at the list of actions that were taken, helpfully compiled by UNESCO, for example, the breadth of the reaction is impressive.

But what was it actually like?

What has it meant to be a teacher when, for example, students can no longer come to school or even connect by phone?

What has it meant to be a student stuck in front of a screen—that scenario Ariana and I expressed concern about—or a student with no screen at all, lost within the system?

What did the system, educators, parents and students actually do amidst the chaos?

The answer, for many, is this: they did something quite extraordinary.

Next week: The equalizers.

https://elcolectivo506.com/current-edition/lessons-learned/following-in-their-footsteps-2/?lang=en