How would the lives of people—and cats and dogs—change in Costa Rican communities if municipalities made pet welfare one of their responsibilities? And could those changes improve the country’s public health?

The new law called “Municipal Service for the Attention of Companion Animals” seeks to answer these questions. It was approved by the Legislative Assembly on January 24 and signed by President Carlos Alvarado on March 30; it will take effect once it is published in La Gaceta, the official government daily. From that moment on, all the country’s municipalities will be forced to create programs for pets in their cantons.

According to the law’s Article 2, “Municipal Service for the Care of Companion Animals is defined as the functions carried out by municipalities to promote responsible pet ownership, humane population control, zoonosis prevention activities, and animal welfare.”

In other words, municipalities will have to take action to control dog and cat populations, which will prevent the spread of zoonoses: diseases that occur in animals and are transmissible to humans. This will require programs that universalize access to castration and vaccination against rabies, and support for pet owners so they can more easily access other basic pet care such as deworming and vaccination at reasonable rates. Finally, municipalities must “foster a culture of respect and responsibility for the ownership of pets” through education campaigns.

How will they fund this work? With funds from the municipal street cleaning tax. The law allows each municipal council to determine the percentage of income from the tax that will be assigned to companion animal programs. What follows will depend on each municipality.

Several municipalities have already put in years of work in this area, which also overlaps with provisions in other laws such as the Law Against Animal Abuse.

Iliana Céspedes, veterinarian in charge of the Animal Welfare Program of the National Service for Agrifood Health and Quality (SENASA), says that she’s forged agreements with 13 municipalities, not only to train and provide advice on population control and animal welfare programs, but also for these municipalities to become authorized implementing partners for SENASA.

“For food safety, veterinary doctors [in a municipality] can be authorized so they can serve as an extra hand for SENASA,” Iliana says. “They people can carry out irresponsible possession actions as if they were SENASA personnel.

“We have only one person from SENASA for every three cantons to oversee [various issues]: safety, medicines, quarantine, animal welfare, all the programs. Now that I have these animal welfare people [authorized] in the municipalities, it is easier for me to act”, adds Iliana. She says this allows her to deal much more quickly with complaints of irresponsible animal ownership.

In order for the municipalities to establish this agreement with SENASA, they must meet three requirements. The first is to appoint a person in charge within the municipality to serve as a liaison with Iliana. The second is to commit to organizing castration campaigns: “What we are looking for is that there is a population [of domestic animals] that we can manage, that we can attend to,” says Iliana.

The third requirement is to carry out joint training programs with other entities such as municipal police, ministries, and the Judicial Investigation Police (OIJ), so that all institutions know how to respond to emergencies and complaints.

“What we want is to get these people to replicate [projects]. We want them to be as effective as Curridabat or Cartago, who have done a marvelous job in their cantons,” says Iliana.

Stray animals and the Municipality of Cartago

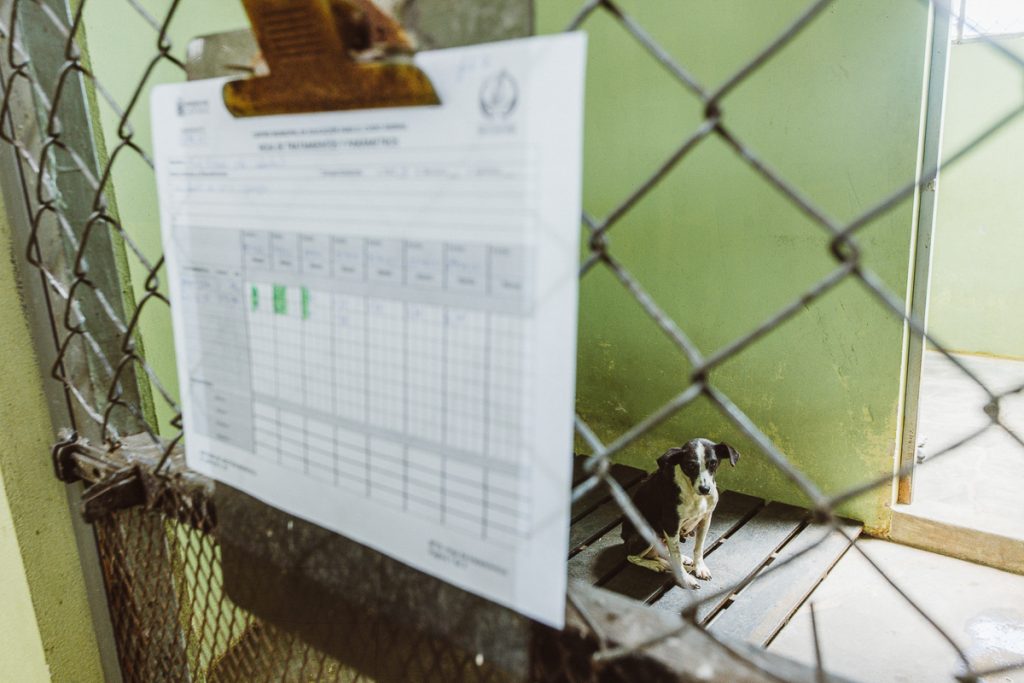

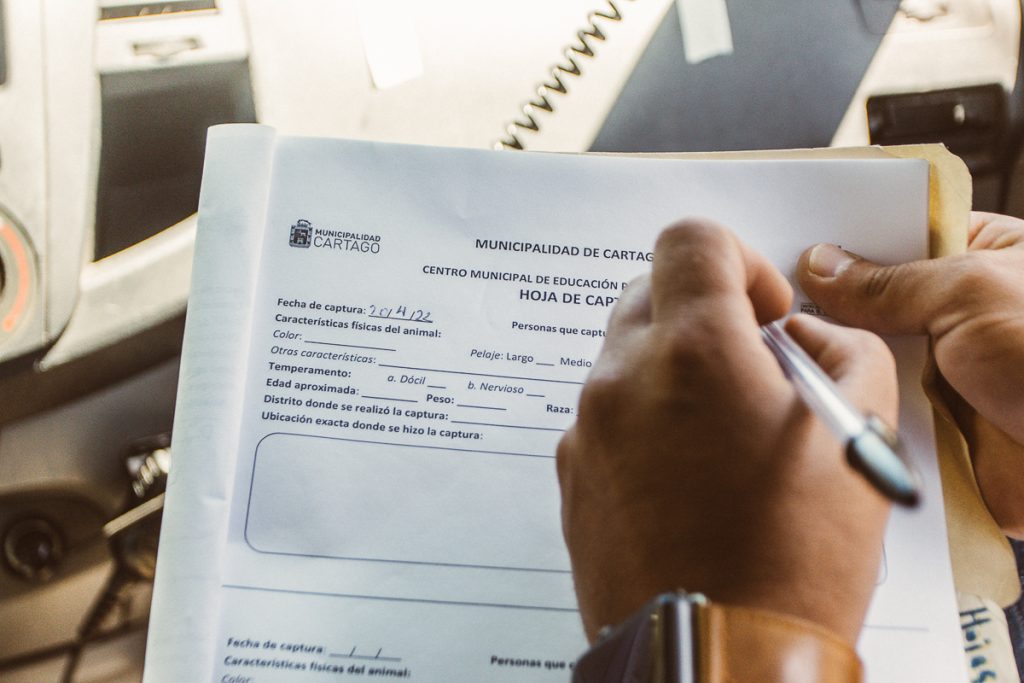

In October 2016, the Municipality of Cartago inaugurated the Municipal Education Center for Animals as part of its department of animal welfare and public health. Its primary mission, in addition to educating the population about responsible pet ownership, is to attend to the problem of stray dogs and achieve control of this population.

“Captura, Castra, Vacuna y Libera” (“Capture, Castrate, Vaccinate and Liberate”), the center’s star program, has become an example across Costa Rica and Central America—not only because of the municipality’s large economic investment in building the center, but also because of the constant investment of personnel hours, equipment, and supplies. As a result, the program has castrated more than 3,500 stray dogs in Cartago to date.

Municipal staff have scheduled routes every week on which they capture dogs found on public roads. The dogs are transferred to the center, where Rafael Hernández Solano, a veterinarian who has worked for the municipality since the beginning of the project, performs a general check-up. He then applies medicines and products to control internal and external parasites, such as fleas. The dogs are vaccinated against rabies, neutered or spayed, and stay at the center as long as they need recover from surgery.

Once they have recovered, the dogs are put up for adoption through the center’s website and Facebook page. Interested people must fill out a form and undergo an interview before adopting one of the animals. If the dogs are not adopted, they are released where they were captured.

Rafael explains that the animals that have passed through the program are notched, or cut on their right ear, to identify them on future capture routes.

“We have realized that in the central districts, most animals have already come through” the center, says Rafael. However, he explains that in the more rural districts, the population has not yet been controlled as successfully. “In the rural districts that we have in the canton, such as Corralillo, they are places where people live without fences or anything. Dogs are everywhere, and they are not castrated.”

Statistics from more than five years of operation allow the center to concentrate its work where it is most needed. In addition, the reports submitted by citizens allow them to find stray dogs quickly.

But it wasn’t always like that.

“When the municipality started capturing dogs on the street, that had not been seen for many years in Costa Rica,” Rafael says. “We had to educate people who said that the municipality was going to take the animals and kill them.

“Another of the great challenges is human behavior. It becomes a vicious cycle,” he adds, referring to citizens who have pets but do not neuter or control the animals. “[The pet] gets out, it reproduces, and that greatly delays being able to reduce the number of animals on the streets.”

The responsibilities of the center and its staff continue to grow, now that an agreement has been signed with SENASA that allows municipal staff to handle complaints of irresponsible possession. Rafael sees this as an improvement in the service, but foresees a considerable increase in work.

“Other things that could help improve the project is to increase our staff,” he says. “If the number of complaints warrants it and we could have an inspector dedicated to dealing with complaints, the impact would be much greater.”

Rafael sees in the future Law of Municipal Service for the Attention of Companion Animals a way to open those doors—not only in his municipality, but also in other cantons.

“Although the animal welfare component is super important, the basis of the project was public health. From this perspective, it should be implemented in all municipalities,” he says. “It’s been proven that unhealthy animals can pose risks to public health. There are types of parasites in dog feces that can enter children and cause blindness. There are traffic accidents caused by dogs crossing the street; cases of aggression against people or other pets by stray dogs; the discomfort of people who can’t sleep because there are cats fighting on the roof. This program has an important public health component.”

In 2021, Rafael and the center’s team decided to carry out a cantonal study on veterinary public health and animal welfare: “We wanted to identify people’s perception of these issues. What problems do you perceive there are in animal welfare and public health? And what possible solutions would you like to see?”

The doctor shared with El Colectivo 506 a summary of the findings of the investigation, which says that the Carthaginians find that the main public health problems caused by animals are “animal feces in public areas, breaking of garbage bags by animals, owners who allow their pets to leave the house without supervision, and overpopulation of stray animals.” Residents observed more stray cats than stray dogs in Cartago.

“The program started with dogs, because at the time, that was the main problem,” says Rafael. “This year, or at the latest the next, it will start with cats, because the study showed that it is a necessity.”

Education on animal welfare and the Municipality of Curridabat

Curridabat is a city of animals with responsible owners. So says the World Animal Protection (WAP), which awarded the Municipality of Curridabat first place in this category of the 2nd Edition of the 2020 Animal-Friendly City Award

Why did they win? Because of animal welfare education programs that the municipality has implemented since 2018. These programs “seek to empower the population on the issue of responsible ownership through educational tools and a voice within the municipal animal welfare program,” according to the WAP.

The Animal Welfare Program of the Municipality of Curridabat is the implementing arm of a public policy that has three lines of action. Like Cartago, Curridabat seeks to reduce the number of street dogs and cats through a capture, neuter and release program, which has focused mainly on the feral cat population.

Tatiana Fonseca, a veterinary doctor from the municipality, explains that this program works only when there is a committed neighborhood or community that works hand in hand with the program. The municipality trains community members on how to capture the cats and lends them special cages. Once the cat has been captured, it is transferred to a veterinarian that has been contracted by the municipality for spaying and neutering. Community members take care of the animal during its recovery; if appropriate, the animal is put up for adoption, and if not, it is rereleased.

This program not only reduces mass reproduction on the streets, but also works hand in hand with the community and raises awareness about the importance of castration.

Tatiana explains that each semester, the program can support between four and five communities, neutering between eight and 10 cats in each. Program staff also answer calls from companies and schools that have a population of feral cats in their facilities.

Another pillar of the project’s work is the offer of low-cost castrations for residents of Curridabat: “We work them specifically in areas of high canine and feline density to cause a real impact. The organization we hired for the service also gives talks on why castration is important and what effects it will have, then following up so that the campaign is effective,” says Tatiana.

In 2021 alone, that organization, the National Animal Protection Association (ANPA), carried out 15 campaigns in three districts (Tirrases, Granadilla, and central Curridabat) for a total of 898 castrations of dogs and cats in the canton. Tatiana says that the program has carried out more than 10,000 castrations since its inception.

The third pillar of the municipality’s work is training its citizens around animal welfare.

Dr. Fonseca and her assistant Drako teach the workshop together. Mónica Quesada Cordero / El Colectivo 506[/caption]

Dr. Fonseca and her assistant Drako teach the workshop together. Mónica Quesada Cordero / El Colectivo 506[/caption]

“The education and awareness program is a giant project called Education for All,” says Tatiana. The program organizes face-to-face and virtual workshops adapted for various demographics: older adults, the general population, young people, and children. The training provided by the municipality ranges from responsible pet ownership and positive training, to how to prevent bites. In 2021, the municipality carried out 19 virtual training sessions and three face-to-face sessions.

With the return to in-person schooling, Tatiana has started a new program that she hopes to bring to all of the canton’s schools, called “Animal Defenders.” This is a series of three workshops to help elementary and high school students learn about responsible pet ownership.

“The main objective is to sensitize children to animal welfare and thus cause a generational change,” says Tatiana. “The purpose is to work towards changing the culture.”

The workshop is currently being taught at the 15 de Agosto School in Tirrases, the canton’s poorest district. The school has 1,500 students and the administration is committed to ensuring that all students participate. So far, 10% of the population has taken part, and a second group of students has now begun.

Tatiana is already in conversation with all of the canton’s school principals.

“It is an ambitious project—I won’t deny it,” she sais. “But it’s a project with a lot of love. The goal is to grow so that other municipalities can replicate it. Education is the way to bring about social change.”