A community project in the dry valleys of Cochabamba increased the population of an endemic species from 807 to 1,160 individuals in nine years, but it faces structural threats beyond local control.

Fabricio Lobaton tells the story in this report, made possible by a grant from the Latin America Solutions Journalism Fund, an initiative of El Colectivo 506, with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network. It was published by Casa de Nadie on November 7, 2025, and has been adapted and translated for co-publication by El Colectivo 506. ChatGPT was used to create the first draft of the translation.

Simón Pedrazas did something no one in San Carlos wanted to do. He raised his hand at a meeting of this community, lost among the dry valleys on the road to Santa Cruz, and said yes. He would become a park ranger for a bird he had spent his entire life killing with arrows and slingshots. A large parrot. Red. The pest that ate the corn. For 1,400 bolivianos a month—less than 30 dollars.

“I went for it because no one else wanted to, and it was so important to have a park ranger,” he recalls 22 years later. “And my farm was doing badly that year because of the drought.”

Extract from an interview of Simón Pedrazas (comunario), 2025.

San Carlos is located in the municipality of Omereque, in the department of Cochabamba, in central Bolivia. To get there from the capital city, you have to travel more than 250 kilometers: first on asphalt, then on a dirt road that winds through rock formations. The landscape is composed of reddish soil, columnar cacti, and free-roaming goats. Temperatures range from 35°C at midday to freezing at night. The adobe houses cling to the hillsides. Drinking water remains a luxury.

Here, along with the neighboring communities of Amaya and Perereta, lives the red-fronted macaw. This parrot measures 55 to 60 centimeters in length. It has green plumage with a red forehead, crown, shoulders, and thighs. It nests on cliffs and feeds on seeds and fruit.

And it is found nowhere else in the world.

This is the story of how three communities went from hunters to guardians. From considering a bird a pest, to a species they now protect because it generates more income alive than dead. From 807 individuals in 2012 to 1,160 in 2021—an increase of 43.7%. It’s the first positive trend in decades for an endemic species that’s critically endangered.

Persecution and deterioration. Why didn’t anyone want to be a park guard?

The red-fronted macaw faces two historical threats: direct persecution by humans and habitat destruction. For decades, communities in Bolivia’s dry valleys waged a war against this bird—not out of hatred, but for survival.

“Before this existed, I remember, we were children, we knew how to hunt, we knew how to kill with arrows,” says Marlene Rivas, cook at the tourist lodge of the Red-fronted Macaw Community Nature Reserve. Marlene is almost 50 years old. She was born and raised in San Carlos.

The macaws fed on the crops, mainly corn and peanuts. They could eat up to 30% of a harvest.

“We plant crops in the fields and want to get the most out of them, but unfortunately, it was also their food. So they were hurting us—they ate a third or almost 50% of it,” explains Armin Vargas, the reserve’s current park ranger. “That’s why we wanted to scare them away, with firecrackers or slingshots, so they wouldn’t bother us anymore.”

Guido Saldaña grew up in these valleys. A biologist, he coordinates the Red-fronted Macaw Program at the Armonía Association.

“My first job as a child was to go and look after the cornfield so the parrots wouldn’t eat it,” he says. Among those parrots was the red-fronted macaw. “It was one of the biggest parrots and the most colorful. And I loved watching it because it was one of the parrots that could actually come down to the ground and walk on it.”

Guido joined the project more than 20 years ago, just a recent graduate student looking for a research topic.

“I stayed with them to support them, and I’ve been here ever since,” he recalls. What was meant to be a thesis became his life’s calling. Two decades later, he coordinates the program he once studied as an object of academic research.

But local persecution wasn’t the only threat. Between 1987 and the early 1990s, illegal trafficking nearly wiped the species out. The traffickers came from the cities. They offered 50 bolivianos per live parrot—three days’ wages at a time when the national minimum wage was 68 bolivianos per month.

“We saw them like in the cages where they transport chickens to market,” Guido recalls. “There were people who would chase them to take them to markets in different parts of the country, even people who were leaving Bolivia. To them, they were just parrots and pests, and to many farmers as well. Sometimes middlemen would come and pay the community members to help capture the parrots. And of course, the community members didn’t know the value of this species and even helped. They said, ‘This way we get rid of these macaws that can damage our crops.'”

The captured parrots were destined for illegal markets both inside and outside of Bolivia. They were trafficked across the borders with Brazil and Peru to Europe and the United States. The endemic species was becoming an exotic pet in the living rooms of the urban middle class.

The habitat was also deteriorating.

“The habitat was much better back then, definitely; it was much greener, there was more rain, the vegetation was thriving much more, and natural regeneration was much more effective,” Guido recalls. The dry valleys have become impoverished: the rivers are drying up, the vegetation has significantly diminished, and overgrazing—especially by goats—has accelerated habitat degradation, along with agricultural expansion and firewood extraction.

The Mizque and Comarapa rivers flowed year-round during Guido’s childhood in the 1980s.

“That’s no longer the case. It hasn’t been like that for several years now,” he says. “This means that the amount of rainfall has decreased, and there has been overexploitation of the vegetation due to the large number of cattle, perhaps uncontrolled and extensive, which has made the habitat increasingly impoverished. To that we add the issue of climate change, which is hitting this area harder.”

By 2012, only 807 red-fronted macaws had survived, according to a census conducted by Spanish and Bolivian researchers with support from the Department of Conservation Biology at the Doñana Biological Station in Spain. Fewer than 100 active breeding pairs remained. The species was classified as Critically Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. In 2021, Asociación Armonía led the national census of the red-fronted macaw across the species’ entire natural range.

But the red-fronted macaw is not alone on these cliffs. Formal inventories that began in 2006 documented 218 bird species in the reserve. Among them are two additional endemic species that were virtually unknown: the cliff parakeet (Myiopsitta luchsi) and the Bolivian blackbird (Oreopsar bolivianus). Three species found nowhere else in the world were sharing a mere 50 hectares of dry valleys.

Bolivia has the second highest level of bird endemism in South America after Peru. However, it lacks sufficient state resources for large-scale conservation programs. The red-fronted macaw, with a distribution range of just 5,000 square kilometers in the dry valleys of Cochabamba, Chuquisaca, Potosí, and Santa Cruz, was critically dependent on local initiatives for survival.

Every surviving specimen became crucial. The loss of an endemic species is irreversible globally, not just locally. Millions of years of unique evolution can vanish in decades.

When Harmony arrived

Sound of the red-fronted macaw.

When Asociación Armonía, or Harmony Association, arrived in San Carlos in 2004, it brought a proposal that sounded absurd: to turn hunters into guardians. To create a community reserve. To develop birdwatching tourism. To make foreigners pay to see the parrot that the communities considered a pest.

“It was hard to believe,” says Marlene. “We said: here, people are mostly involved in agricultural work. Those skilled people can’t be found here. Who would want to work there? We’re all working here in the pastures, doing agriculture. It seemed impossible to us.”

Armonía was founded in 1996 as a Bolivian nonprofit organization affiliated with BirdLife International. By the early 2000s, it had grasped something crucial: in Bolivia, with limited state resources for conservation, success depended on the active commitment of rural communities that shared territory with threatened species.

Extract of an interview with Guido Saldaña, 2025.

In 2006 and 2007, when the reserve was formally established, birdwatching was seen as something silly.

“People would say, ‘Birdwatching: you’re wasting your time. What are you doing? You must have nothing to do. You’re idle.’,” says Guido. “That’s what even the community members told us when we started with this idea.”

But birdwatching tourism wasn’t the only idea Armonía brought to the table. The association arrived with a multifaceted strategy.

“What we did was complement it with other projects related to agriculture, because agriculture is the fundamental basis of these communities. But they are also compatible with the environment,” Guido explains. These included projects to improve quality of life and drinking water systems, as well as organic peanut and corn production workshops that reduced the use of expensive agrochemicals.

The proposed conservation model was revolutionary in its simplicity: the communities would have absolute ownership of the territory, of the tourist lodge, and of all decisions. Armonía would provide only initial technical support.

“The Reserva Frente Roja is actually land that belongs entirely to the communities, and they are the ones who have designated part of their land to be used as a Community Nature Reserve,” says Guido. “They own the land. The tourist lodge is also part of their property, so the entire project belongs to the communities. We, as a project and as Armonía, provide technical support.”

This model of community ownership was deliberate.

“From the beginning, we always started with this concept: [the community members] live in and have one of the best nesting areas and populations of red-fronted macaws in the world,” he says. “So, from there, they began to give this site a little more importance.”

Months of meetings ensued. Armonía showed photos of Costa Rica and Ecuador: European tourists, thousands of dollars spent to see birds. The communities did the math. In 2006, they formalized the Community Nature Reserve and built a lodge.

But something crucial was missing: someone willing to be a park ranger.

“At first, nobody wanted to be a park ranger,” Simón recalls. “It was so important to have a park ranger, but nobody dared.” Until Simón raised his hand. His farm was failing that year due to the drought.

Simón became the first community park ranger. His job: walking the canyons looking for nests, counting macaws, scaring off poachers, learning to fill out monitoring forms.

Marlene arrived differently. Not as a park ranger—as a cook.

“They asked me if I could prepare lunch for some visitors,” she says. “I made them pique macho. They liked it. They asked if I could come back tomorrow.”

Marlene had small children. She didn’t think she could do it. But she agreed to try. First, she was a volunteer for a whole year.

“I was afraid, but then when I came, I saw how they did things and I became interested. Then, just like that, I started working too. I liked it and I said, ‘Oh, no, here I can stay and work instead of working in the fields, in the sun. Here I can get a job.’”

The hardest part was learning to cook for foreigners, especially vegetarians: “That’s been really difficult for us. Sometimes they ask for varied vegetarian meals, because they’re allergic to many things they can’t eat. People here are used to working in the fields, and in the fields, you eat the food they give you. You don’t have to be preparing one thing after another. Foreigners are treated very delicately. It seems to be very difficult for them.”

Marlene didn’t request formal training: “I just asked for menu cards like these so I could make things, so I could learn. It’s been hard to learn, but I’ve learned little by little, and I’ve enjoyed it.”

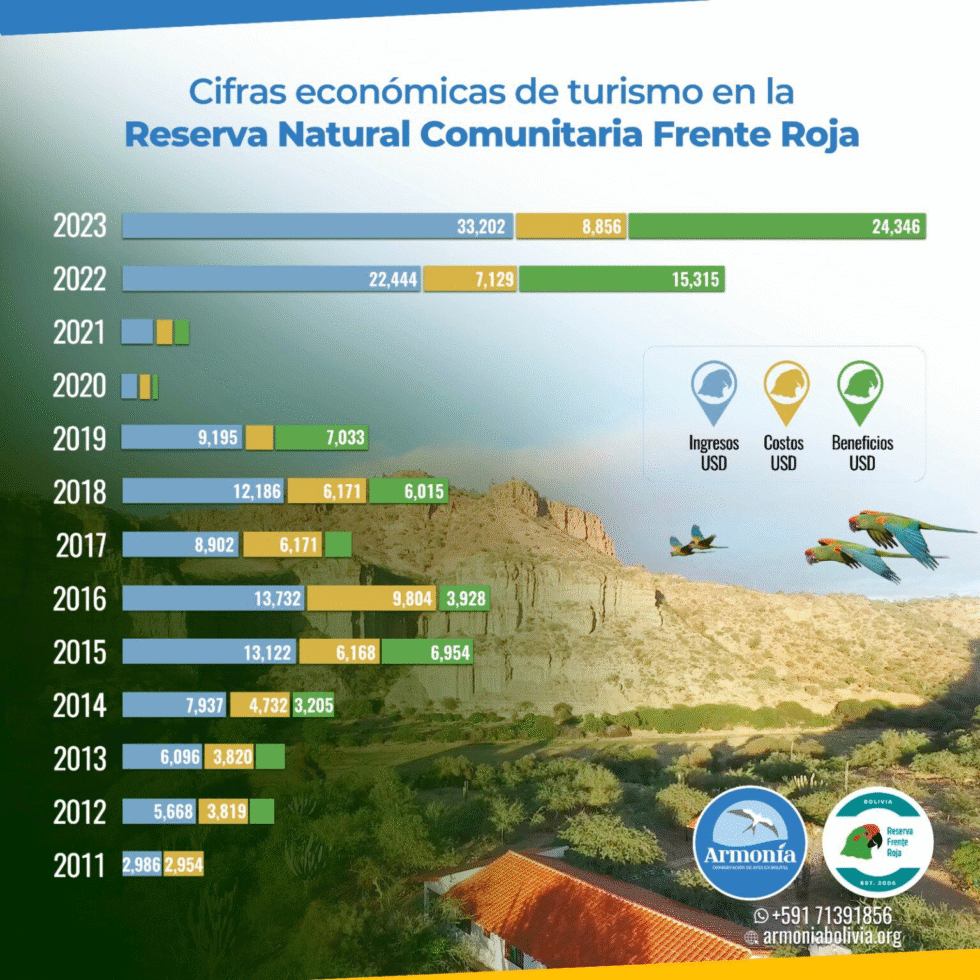

The first group of tourists arrived in 2008. That entire year, they received only 10 visitors. The numbers grew slowly: by 2023, the reserve was receiving 137 people. Tourism was generating income that the communities had never imagined from a bird they had previously considered a pest.

The economic model was structured transparently. Tourism revenue is divided at a quarterly community assembly. A local management committee with representatives from the three communities makes decisions. Part of the funds goes toward the maintenance of the reserve and the lodge. Part goes toward park ranger salaries. Part goes toward community projects voted on at the assembly: water systems, school improvements, and support for families living in poverty.

“At first, the communities always said that everything generated was for their benefit and they didn’t allocate any of it for sustainability,” Guido recalls. “It was a bit difficult to make the communities understand that. It’s been a lot of hard work between the project and the management committee to make them understand that those resources also have to be used to continue improving the reserve and the tourist lodge, to have better conditions for serving visitors.”

But that changed: “Today, we have a very positive attitude from the communities on the committee to continue improving with the funds generated by tourism.”

Conservation efforts include population monitoring using standardized scientific methodologies. They protect critical nesting and feeding sites, and monitor for threats such as illegal capture and habitat disturbance. The wardens conduct regular censuses, protect communal roosts where the macaws congregate, and develop environmental education programs in local schools.

A key strategy was to produce corn and peanuts specifically to feed the macaws during the dry season.

“Some good ideas have emerged here about producing peanuts, and that’s what we feed them. We also produce peanuts,” explains Marlene.

“We give them the peanut product, which we, the community members, produce ourselves,” adds Armin.

It’s a community area where no one scares the birds, where they are allowed to feed freely, and where we both live peacefully.