“¿Cuantos lleva?”

I asked this question—how many are there?—as I realized that this man wearing shorts and a hat, as if he were strolling through a beach town, was counting the people in line. I’d arrived at the Calderón Guardia Hospital in downtown San José one hour earlier, hoping to get a slot for one of the 1,000 Pfizer COVID-19 vaccines the hospital was administering that day to any person over 40 that wanted to be vaccinated.

“460,” he answered, pointing at the lady right before me. Johana and I met at dawn when we both showed up at the end of the line, both very unsure about our possibilities of making it to the front. She works at a private hospital and was vaccinated a long time ago, but her husband is still not vaccinated, so she and her 16-year-old son got up early this morning and came to wait in line on his behalf.

It was Saturday, July 17th, 2021.

On Tuesday, July 13, Costa Rica received half a million Pfizer doses as a donation from the USA. For a population of 5 million, and a government that has been administering its slow trickle of vaccines as quickly as possible in hopes of reaching herd immunity, this big load of vaccines makes an enormous difference.

The biggest immediate impact is for people like me, older than 40 years and younger than 57 and with no health risks. Up until last Tuesday when the donation arrived, it felt almost impossible for me to get a vaccine in 2021 here in Costa Rica.

According to the Costa Rican Social Security System (CCSS), Costa Rica had administered a little more than 2.6 million doses as of July 13; 822,842 people had received two doses. This means that 16.3% of the population are fully immunized and another 19% of the population has received at least one dose. Those statistics correspond to what the Costa Rican government denominated as Groups 1-4, which contain senior citizens, medical personnel, people of all ages with high health risk factors, and public workers in close contact with others (such as garbage collectors). Vaccines are distributed by the public health clinics assigned to each community, with health care workers working their way through their lists, but the new U.S. donation has required the government to unload vaccines quickly through the country’s first COVID-19 mass vaccination campaigns.

The 500,000 doses now being administered in the campaigns taking place until July 26 will add another 10% to those statistics and will include people older than 40 with no health risks, part of Group 5). This will help Costa Rica reach 45% of the population with at least one immunization dose against COVID-19.

Saturday was my second attempt to participate in the massive vaccination campaign, which is being run at various public institutions around the city and country. The day before, opening day, I arrived at the National Institute of Learning (INA) at 7:25am, five minutes before opening; and the line was already 1 km long. I decided to turn around and try the next day at a location closer to my house. That Friday, hundreds of people got their first dose of Pfizer vaccine at INA.

On Saturday I left home at 4:55 am, five minutes before the night’s COVID-19 vehicular restriction was over.I drove up to the beginning of the line at 5:05.

Naively, I got out of the car there and started walking back along the line, thinking that it couldn’t possibly be that long at this early hour. I ended up walking around 300 m, watching people sleeping in comfortable camping chairs, reading books, having breakfast, or engaged in lively chats. While I was dismayed by how long I’d have to wait, this also felt like pre-COVID times, somehow: when we all gathered for a particular goal and made a community during that sometimes long wait.

During the first hour standing in line, I got to get to know my new community.

Beatriz is 60 years old and arrived a few seconds behind me to stand in line for her son-in-law. She has been vaccinated for a while. She remembers March 8, 2020, very clearly: coming back from a dance hall and talking to her nieces about the spread of COVID. Since her vaccination, she has gone back to her afternoons on the dance floor, but she claims she’s very careful. “Sometimes I’m the only one on the floor with a mask on,” she said.

Her son-in-law, Fran, showed up at 7 am. He’s immediately subjected to some gentle razzing from the community that’s now been bonding for two solid hours (as in, “Hey man, nice of you to show up!”). “She does that for everybody,” he said about his mother-in-law standing in line for him, and then proceeded to thank her profusely. Fran was even more chatty than Beatriz. He said he was very happy to get the vaccine, not only because he will be safer, but also because “we can get someone else sick,” he said.

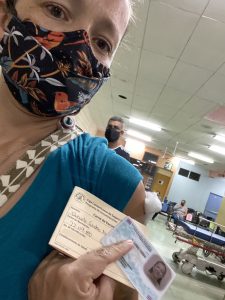

By 7:15 am the line was finally moving. Johana, my neighbor in front, had paid a visit to the beginning of the line and came back with information: there were already 40 people inside. She also saw CCSS officials giving numbered tickets to those in line, making sure those who got up early would not be cheated. When I finally got my ticket in hand, I felt even more relieved and happy. I was set to receive dose 437 of the day.

Almost an hour later, Fran decided to preach to me for about 10 minutes. He started by telling me that he was raised by his grandmother in the southern part of the country, where he was first introduced to evangelical beliefs; at the age of 7, he moved in with his mother and became Catholic; at age 10, his father took him to the Central Valley and introduced him to the Jehovah’s Witnesses. After all that, and another time spent inside Catholicism, he joined an evangelical church. He is a strong believer in God, but he has also come to other conclusions. “All they want [religious entities] is to make money,” he said. “They don’t want to save us.” I told him that on this point, at least, we can agree.

By now our little community had become very close and cheerful. We could see how the line is advancing and felt happier and more relieved with every step. Behind Fran and Beatriz, a couple had become the life of the party. He got an appointment to get his vaccine at his assigned public clinic on Monday, but his wife hadn’t heard a thing, so they decided to come and get vaccinated together. They seemed like high-school sweethearts, hugging and kissing, and sharing a very nice breakfast they had in their backpack. The man soon started to entertain all of us, joking and singing as inspiration came.

At 9 am, a very angry man showed up in his fancy truck and parked right in front of us. Why was he angry? Because he had arrived too late to get a shot. For 15 minutes and without wearing a mask, he proceeded to talk about the government and what he considers a failure in handling the pandemic and the immunization program. “People should not be standing in line,” he said. “In other countries they just send your vaccine to your house, and you inject it yourself.”

While his assertion is untrue, it’s a fact that public health workers in some places in Costa Rica have achieved door-to-door service. In the Central Valley and some of the bigger cities elsewhere in the country, 15 mass vaccination centers will apply an assigned number of doses to the people that show up on time each day. But in some smaller towns, public health teams are inviting people to stay at home and wait for their personnel to come to their door to administer their vaccine. Some other parts of the country have even created AutoVac, where people do not even have to get out of the car to receive their dose. Every local team, or EBAIS, will continue their ongoing labor of making appointments for the people that they have on their lists, until they run out of doses.

I, and everyone around me in that line, could have waited for the appointment, but we were all too eager to get the vaccine.

Such is the case of Johana, who had a difficult time finding a cab this morning so she could come and stand in line for her husband, Pablo, a 49-year-old municipality employee. “He’s so indecisive,” Johana said about Pablo. “He was telling me yesterday that he would wait for the appointment.”

However, Pablo, who joined her shortly after sunrise, says that because he has some connections in the Montes de Oca Health Area, where he would need to be vaccinated, he learned that he probably wouldn’t get his appointment until September or October. So he let his wife take him to Calderón that morning.

“These are the most productive hours,” Johana said when we had been in line for about five hours. “I would probably be sleeping at this time,” Pablo added, implying that it would have been a waste of his time.

The man who was counting us earlier passed by again around 10 am. He was a character who was hard to miss. Johana and I decided to stop him and asked him what his number was: 563. He also informed us that at the door of the hospital, they were about to let in number 323. He was carrying boxed food and juice; he told us that when he got to the line, around 5:30 am, he decided to count the people to make sure he was going to get one of those 1,000 shots. “If not, I would have been out of here,” he said very theatrically.

We continued moving forward in line. The last few meters felt like a race. Faster and faster, we got closer to the door.

At 11 am sharp I was walking out of the old “Consulta Externa” of the Calderón Guardia Hospital with a shot in my arm and an official appointment for the second dose, October 9, no specific time. All 1,000 of us would have to come back that day.

“If you need me, you can find me at the Muni,” Pablo said, walking right next to me as we left the building.

His comment made me realize that I’d got a lot more than what I came for that day. I walked away with the heartwarming feeling that maybe we can go back to the old normal, where you talk to strangers and make connections in the oddest situations, where you feel that communities can be created with no danger to our health.

As I walked away, I looked back and saw Beatriz waving cheerfully at me. She was waiting for Fran to come out after his vaccine. I hope he took her out for a nice breakfast, just like he promised.