The Namaldí Rural High School—located in the Bajo Chirripó Indigenous Territory, in Matina, Limón—is part of a very interesting community because of its diversity. The mother tongue of most students is Spanish, but the indigenous population speaks the Cabécar language.

I have been an English teacher since 2011. During these years, approximately 108 students have graduated from our high school. They’ve received extensive support from the school itself and from universities, especially for young people seeking to continue their studies after graduation.

Despite this, our students are often people with few personal aspirations due to the environment that surrounds them, characterized by limited job opportunities. However, there are always some students who try to rise in the face of adversity.

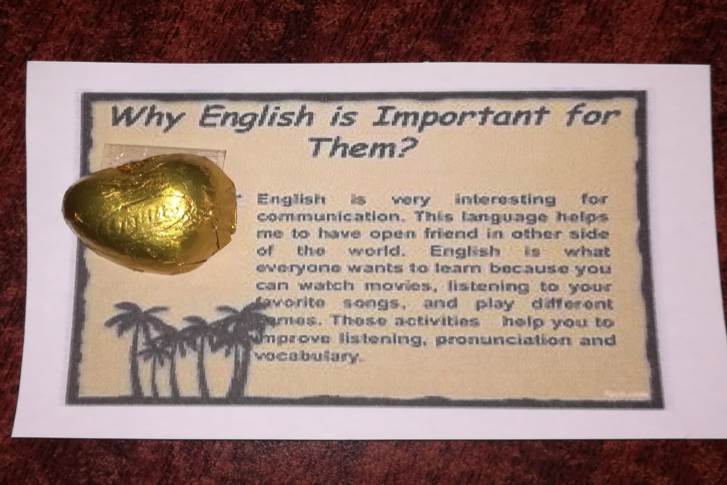

That’s why one of the biggest challenges in this context is getting students to see the importance of academics. Family contexts, due to the fact that most families have low levels of academic achievement, can make it hard for them to see the value of school, much less the importance of English.

One of the most serious family problems is the fact that many young people see attending school as a hobby. When students have little interest in learning, and parents or guardians have little interest in supporting them, their work suffers as a result. Another challenge is to ensure that English is studied not under the parameters of just another subject, but rather as a universal skill that can permeate many aspects of our lives.

However, the fact that English is the third language for some of our students actually makes it easier for them, as experienced language learners, to grasp the pronunciation of English and to advance in their speaking skills.

As a teacher, I have learned that engaging students directly in the teaching-learning process—that is, making activities that are student- and context-centered—is the key to success.

When working in an indigenous territory, I try to identify what my students are already familiar with so that they learn vocabulary from their context. From there, I can personalize their learning and language acquisition.

For example, in seventh grade—the first year of high school and the first year of English for some of my students—I normally use units translated into Cabecar so that students will be able to understand English more clearly. This takes into account that the elementary schools where the students come from do not teach English. Likewise, I try to ensure that first-year students have vocabulary terms in the Cabecar so that it is easier for them to understand the meaning in the context of their mother tongue. What’s more, we always start our conversations in Cabecar so that indigenous students have a preamble in their first language of the basic English conversation to come.

It is incredible how helpful it is to take advantage of students’ foundation in their native language when working on second or third language acquisition.

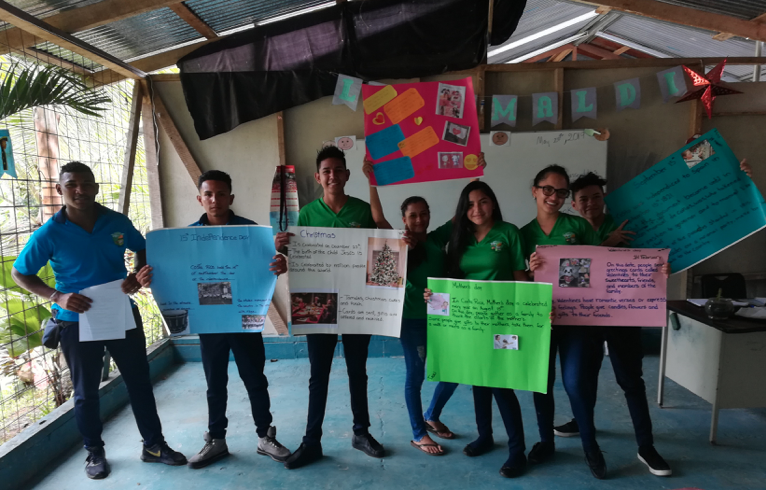

During our English festival this year, students had to make their presentations without the help of the teacher in order to demonstrate their interests and language skills in a self-directed way.

Such was the case of an 11th-grade student, Allison, who gave a presentation on Cabecar customs, comparing them to some U.S. customs. She focused on diet and nutrition, exploring the products that are consumed in each culture. She also talked about pastimes that both cultures have in common, and the difficulties that exist in rural towns compared to urban areas.

It was exciting for me to see the positive and assertive comments of the invited judge. The experience showed that when someone sets an objective in his life, she can achieve it—regardless of the obstacles in her path.