What has pandemic education meant to you?

Have you experienced it as a parent, teacher, grandparent, onlooker? In Costa Rica, or somewhere else in the world? Our month-long March edition is a deep dive into the experiences of educating our children and adolescents during the pandemic, and what lessons we’ve learned that could be applied in the future. During this month, we’d love to hear from you about your perspective on the crisis, and we’ll work hard to portray as many of those perspectives as possible in our coverage. (If you have a story or comment to share, please contact us: [email protected].)

We want to ask the same questions of ourselves that we ask of our readers… so today, we begin this series of stories with the experiences of the three co-founders of El Colectivo 506.

Breaking down classroom walls

By Katherine Stanley Obando

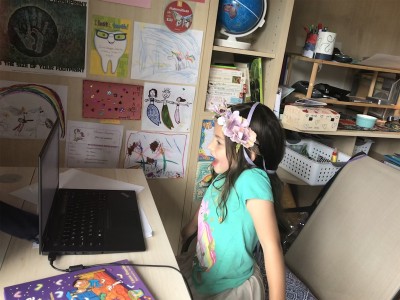

The pandemic shrank our world to the size of our house, but it blasted the lid off my daughter’s education. She could connect with her teacher from anywhere, learn fun facts from her uncle in China, study the ants in our park or the animal tracks at Tapir Valley in Bijagua. All the things we’d weighed and measured in choosing her primary school just months before—she’d started first grade in February 2020, and loved the weeks she had before COVID-19 descended—suddenly disappeared into a vacuum: the distance to and from the school, the daily schedule, what the classroom looked like. As my daughter got more and more frustrated with video classes, the questions I’d pondered in the past about her education transformed from little nagging voices in the back of my mind to giant philosophical quandaries that stomped all around the house, all around my imagination.

What does it mean to be educated, anyway, when you are seven years old? Why can’t we rip the walls off their experience at that age and send them out into the world—which, if you are a child in Costa Rica, where spectacular birds might hop into a cement laundry yard or fascinating ant behavior might be displayed on an urban sidewalk—is a particularly extraordinary place? I wondered about this as we waded our way through seas of papers sent through the school, forgot deadlines and class times, panicked and sighed. We refused to sit her in front of a computer for hours on end, and tried to fill in the gaps ourselves; as my work obligations grew and I handed off more and more of this work to my husband, I sometimes felt that I was drowning in guilt. We somehow squeaked through the requirements for first grade and figured out an arrangement that might work better for second. Education became not something we sent her to go out and acquire, but something we were going to have to figure out for ourselves.

As with so much else in this pandemic, the one thing I know for sure is that there will be no going back to normal. Not completely. After the possibilities I’ve glimpsed during these long months and the protagonism we’ve had to grow into as parents, I know that whenever she can go back to a classroom, we’ll look at it differently. We’ll expect her schools to break down classroom walls and root instruction in Costa Rica itself, with all its richness and complexity. Most of all, though, I think we’ll expect more of ourselves. More, which sometimes means less: because perhaps the biggest lesson we’ve learned is how important it is for kids to find their own way.

Tapirs and cows were our assistant teachers

By Pippa Kelly

The change the pandemic brought in terms of our routine of education was pretty severe. Our kids no longer got on the school bus every day to go to the Escuela El Jardín school in the neighboring town of Bijagua. But their learning did not stop: in many ways, their learning changed and developed in a whole new way.

For me, learning has never been restricted to a classroom setting. My children have always engaged in online learning from Australia, embracing their dual citizens with a dual curriculum. Nonetheless, the pandemia managed to shift us away from the four classroom walls even more and showed us that learning can occur anywhere. There is such deep and rich learning available outside of classrooms, within our own environment. For us it meant working with tapirs, working with local experts, connecting with friends overseas, really getting into reading. In a way, for me, it has been very positive to show children that learning isn’t just restricted to a school building.

This is our normal, our reality, one where I get to see my kids grow up in front of me. I get to be involved in their learning.

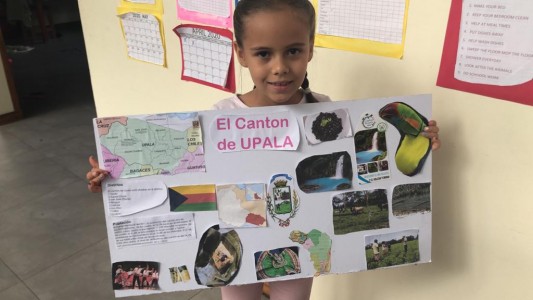

My children are enrolled in a very small rural public school in the north of Costa Rica. Because the community has a low socioeconomic level, the school did not organize any virtual classes. The students were given a pack of paper guides each month: they would work through those at home and submit them at the end of the month in exchange for a food subsidy. They had a Whatsapp group call every week where they could ask different questions to their teachers.

I’m grateful that my children were not stuck in front of a computer on Zoom with real time clases. I saw a lot of children suffer during this time, and a lot of parents suffer as well. I am grateful that we were able to complete those paper guides at home in our own pace—10 minutes before dinner, 15 min after shower in the morning—and then go and explore the farm, plant vegetables, walk the trail, take photos of a tree and then Google it and upload photos to MyNaturalist. I’m glad that we could fit in the obligatory written work according to our schedule. I am grateful the teachers kept in contact with us via Whatsapp and that we were able to learn at our own pace.

I am grateful that this process really involved my husband in the kids’ education. He got to see them every day, teaching them how to milk the cow, how to take care of the garden, teaching them about conservation, about tapirs. He also got to see his children grow.

This is the new normal. We need to move forward, adjust and adapt. We need to be flexible about changes of routine and where learning might occur.

Not mandatory, but wanted

By Mónica Quesada Cordero

He didn’t have to go to school at all. My son had just turned three, and until then we hadn’t sent him to daycare. But we really felt that it was time and that he needed it. So in early 2020 we finally enrolled him in kindergarten, and on the first Monday in February we dressed him in his new uniform and brought him to class, with books and everything.

The school to which his daycare belongs was among the first to close temporarily, before the official order of the Ministry of Education. It reopened for a week after Easter, and then the official order arrived. The weeks were filled with 45-minute virtual sessions three times a week and homework to work on his books every day – but my son didn’t have to do all that.

Meanwhile, we saw our income disappear, since we are a family that depends mainly on tourism. We began to question whether we could sustain, financially and emotionally, a formal education that my son was not required to receive. If we stopped paying for daycare, we would save money and stop feeling guilty about not doing work and participating in virtual sessions, which were of little interest to my son. But what would happen to those teachers and that institution that depended on that income? Just an endless chain of frustration. My husband and I split the day to spend with the kids and try to keep working and inventing new ways to earn income. I took over the tasks of kindergarten, and my husband excelled with coming up with creative activities. But the frustration did not stop growing.

Finally, in June, the daycare reopened. Only five boys and girls returned, and all parents agreed to extend our bubble safely.

Life regained a bit of order. My son returned to playing with his beloved new friends. My one-year-old baby once more got some attention just for him during at least part of the day. We ended the year with virtual graduation. We were very lucky: not only did life have some structure during 2020, but our son had the learning and socialization space that he was not obliged to live, but that we, his parents, really believed that he needed. I was left to wonder: how did parents fare who couldn’t access this support? What does this mean, not just during the pandemic but during regular life?