The final installment in our four-part series on education and the pandemic in Costa Rica, inspired by a 2006 series by our co-founders that followed three second-graders through their school days in three very different Central Valley schools. Read Part One,”Following in Their Footsteps,” here; Part Two, “Inequality and the Virus,” here; and part Three, “The Equalizers,” here.

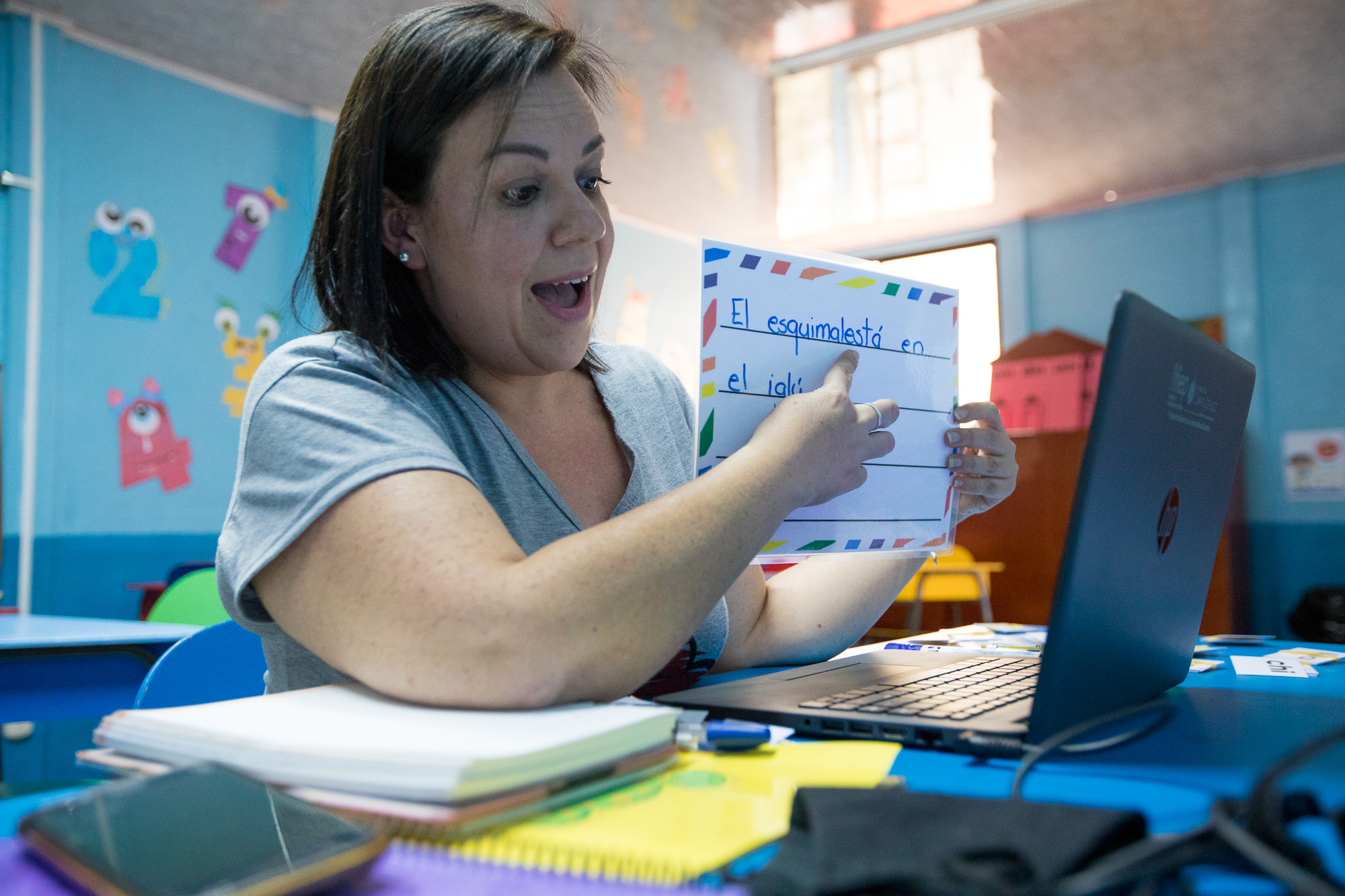

“No, my love. Remember that you can’t hug me,” the teacher says.

She’s extricating herself, gently but firmly, from the grasp of a little girl wearing a Frozen mask. The teacher has opted for a leopard print mask. Her hair is a flash of bright red. The girl, standing outside the Escuela La Carpio waiting to be admitted as part of the 12:30 pm group on a hot day, had visibly fluttered with excitement when the teacher approached, the way kids sometimes do, and wrapped her arms around that comfortable waist.

But this is March, 2021. No hugging allowed.

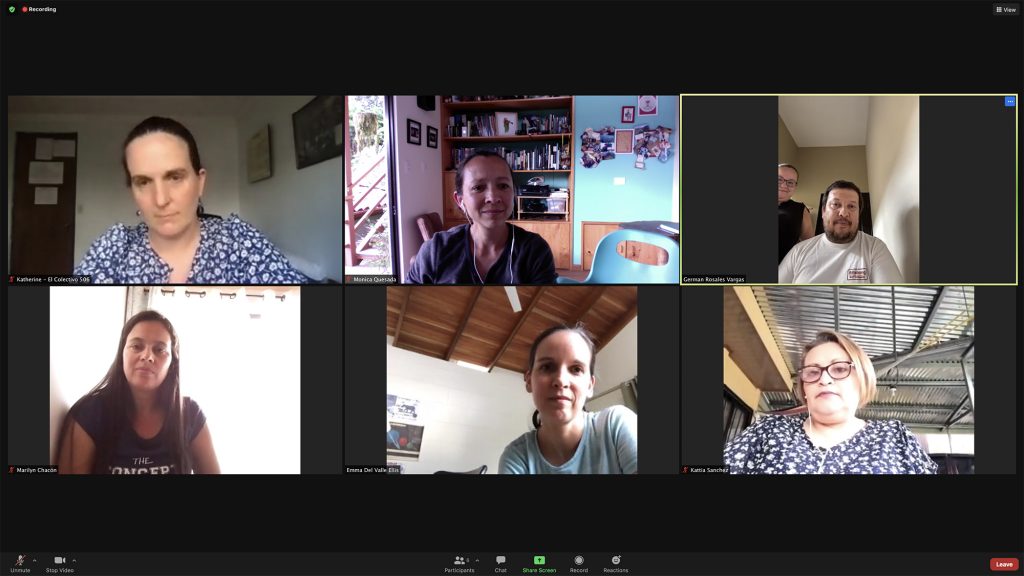

The moment elicits an audible gasp from the adults looking on, including my colleague Mónica Quesada, including me. It’s heartbreaking, and brings instantly to mind layers and layers of moments like that with our own kids: explaining why they can’t play with their friends or see their grandparents. Still, this wave of sadness is just one of the currents of emotion on this day at the Escuela La Carpio. The biggest, overriding current is awe.

If second-grader Greivin Cruz walked back into his school in La Carpio today, in 2021, he might not even notice the masks and alcohol gel, the yellow dots showing parents and kids how to socially distance as they wait to get inside. He’d be too busy gawking at the building itself.

Gone are the overcrowded classrooms, so noisy because the walls between them were so thin, so hot because of the lack of ventilation. The new building, built through a massive collaboration between the Inter-American Development Bank and a host of Costa Rican public institutions, features four stories of classrooms that overlook a large central courtyard, breezes flowing throughout the structure.

La Carpio special-ed teacher Marielos Méndez, whom I met during our 2006 series and who wrote a piece about the new school for me at The Tico Times when it was inaugurated in 2018, reminded readers that this was no overnight success. The first school, the Escuela Finca La Caja, had been put together piece by piece by the community over many years (the first school “featured a few classrooms made out of wood and tin… classes were given in churches or in the hallways of neighbors’ houses,” she wrote). In the same way, the second school was the product of decades of lobbying for better conditions for the parents of kids like Greivin. “It was more than 20 years of waiting, of battling, of requests and paperwork,” she recalled.

If you skipped all that and just returned to see the result, it does feel like a deus ex machina had descended on La Carpio, investing $6.4 million, as the Bank did, and completely transforming education in this low-income community. School psychologist Rosibeth Alvarado remembers how the old building received Health Ministry attention because of its insufficient water supply: teachers and students had to carry around containers of water to flush the toilets and buy water to make up the difference. While we can’t go inside the classrooms because of COVID-19 protocols, Alvarado tells us about the interactive smartboards and other technologies hidden within, “like the ones many private schools have.” Even if the old school had received a donation of such technology, the thin walls wouldn’t have been able to sustain a smartboard, she says.

“This was a way to provide dignity to the whole La Carpio community,” she says of the new school.

It will be fascinating to see the impact of cutting-edge infrastructure on this student body. Of course, that time has not yet come: shortly after the facility’s inauguration in 2018, teacher strikes shut down school for more than 80 days. Just a year after that, the pandemic shut this facility down completely. And while La Carpio is squarely in the heart of Costa Rican urban life, only a half hour from Juan Santamaría International Airport and 20 minutes from the heart of downtown San José, Alvarado says the number of students who had enough home connectivity to take lessons via the Education Ministry’s Microsoft Teams platform was “minimal.”

Almost all of the Escuela La Carpio’s 1,870 students simply filled out the printed “autonomous guides” that were handed out each month along with food packets from the Ministry. The instruction they received from April through November 2020 was limited to whatever their parents could provide.

In this, the kids of La Carpio were not alone. The Public Education Ministry (MEP) estimated early in the pandemic that 500,000 students lacked home connectivity, and could connect with their teachers only through WhatsApp, if that. The State of Education report released an article on July 21, 2020 showing that while 67% of Central Costa Rican students had some kind of connectivity from their homes, 29% could connect only by phone; in rural areas in the Caribbean, Northern or Southern Zones, those numbers drop to 40% for home connectivity and 20% who can connect only through a phone.

Figures for school coverage are much better, with about 87% of the country’s schools possessing some kind of connection. However, our conversations with teachers and parents quickly showed that connection speeds vary significantly. “Our school is connected” is only worth so much if the connection can only tolerate one or two teachers online at a time.

What if, as in La Carpio, a deus ex machina could provide an influx of funds that would resolve this massive infrastructure problem—a problem of digital infrastructure in this case, rather than school buildings?

What if those funds already existed?

What if they totalled, not $6.4 million, but $352 million?

What if they were not being used—that is, not to their fullest potential?

How we got here

To understand Costa Rica’s connectivity problems in 2021, we need to go back to 2006, when I wrote and Mónica photographed our original education series. When we weren’t following Greivin, Ariana and Steven through their second-grade lives, we spent many of our other reporting hours tramping through the streets of San José, covering protests related to the Central American Free Trade Agreement with the United States and the Dominican Republic, or CAFTA-DR. (Just typing those words as I did hundreds of times in those fraught years of debate, my fingers fall into a familiar pattern.)

The objections to the agreement in Costa Rica were many, but one of them was this: that by obliging the Costa Rican government to lift the telecommunications monopoly then held by the Costa Rican Electricity Institute, or ICE, the agreement would rob the country of one of its assets. Since the ICE was publicly held, it installed infrastructure even in tiny towns. With that monopoly lifted, access to phones or, now, internet connection, would be at the mercy of international providers, and therefore increasingly unequal. That was the argument communicated to me at march after march by members of the public and, oftentimes, members of the ICE workers’ union.

The National Telecommunications Fund (FONATEL) was born in that context. Once the CAFTA question was, quite unusually, decided by a national referendum in 2007, the National Telecommunications Law drafted in 2008 to regulate the opening of the market included the stipulation that the Telecommunications Superintendency, or SUTEL, would charge all telecom providers a canon that would be used to pursue “the objectives of universal access, universal service, and solidarity.” The funds would be managed by SUTEL according to priorities and goals established by the Executive Branch.

Therein lies the rub. A review of some of the commentary related to the progress, or lack thereof, of FONATEL, which by late 2019 had amassed a value of $352 million, shows contention and finger-pointing took place nearly from the start. Was SUTEL being too slow to act, or was the government being too slow to provide direction and facilitate processes? A February 2011 staff editorial in La Nación denounced the fact that “two years since its creation, not a single staff member has been named to administer the system, and FONATEL has not a single plan designed.”

A 2013 review of the impact of CAFTA, five years on, by the State of the Nation think tank, noted that FONATEL “has been criticized because of the amount of time SUTEL took to create the trust and select and hire an administrative consulting company to implement the program… [and] for its lack of coordinated investments (computers in schools, health applications and systems, training for teachers and other officials). The report notes that SUTEL responded to these criticisms by complaining that the Telecommunications Law allowed it to spend only 1% of its funding on administration, that Costa Rica’s public contract regulations had slowed it up, and that other ministries weren’t complaining.

In March 2021—that’s 13 years since the fund’s creation, eight years since that State of the Nation report, and one year after the start of a global pandemic that made school and student connectivity an urgent priority—fingers are still pointing.

“One of the biggest lessons learned is that we’ve wasted a golden opportunity,” says Paola Vega, Minister of Science and Technology, of FONATEL and educational connectivity in Costa Rica. Having taken office in June 2020, shortly before that State of Education calling authorities to task for the lack of progress in closing the digital divide, she’s led an energetic effort to hasten the process and is now promoting a bill in the Legislative Assembly that would put her ministry (MICITT) and the MEP in charge of implementing FONATEL programs.

In our lengthy interview on the reasons FONATEL had not accomplished more in the 11 years between its creation and COVID-19, Vega painted the picture of a mess that combines multiple challenges familiar to any student of Costa Rican public policy.

There’s the lack of continuity: since each presidential administration takes a different approach to connectivity and the National Telecommunications Plans last only six years, it’s hard to maintain a consistent strategy, she said. At the same time, there’s a lack of revision and flexibility: the country’s 2008 National Telecommunications Law, drafted once CAFTA was approved, should be reviewed and adjusted much more frequently, she said, especially given the vertiginous pace of change in technologies and needs. And, according to Vega, there’s an expectation of consensus that impedes effective action: while, in theory, FONATEL must respond to government requests, those requests trigger needs assessments, feasibility studies and telecommunications providers’ technical opinions. No one has the authority to force action.

“Who has the last word?” asked Vega, arguing that until clear leadership is established, implementation problems will continue.

Also very typical: there are now multiple solutions on the table. The bill to shift power to MEP and MICITT is only one of several initiatives afoot. SUTEL and the chamber of telecommunications providers oppose the bill, arguing that changing which entity holds the reins won’t improve the process; meanwhile, a total of three other legislators have introduced bills to reform the use of FONATEL in still other ways.

Progress continues. SUTEL, which had not granted an interview by press time, sent over its indicators via email, showing progress in some areas and large quantities of “committed” funds to be executed in the next few years. However, in terms of the immediate and ongoing problem of how to connect kids to Teams right now, the biggest news in recent months was an effort by that entity on the line back at those protests in 2006: the ICE. Its brand Kolbi has launched an alliance with the MEP to provide unlimited monthly access to MEP platforms for 2,000 colones (about $3.50) per month, a significant savings considering that an hour of Microsoft Teams access costs about 2,500 colones. The alliance will cover up to 200,000 families until June, when it will be reviewed and potentially renewed, Kolbi marketing manager Jacqueline González told me this week.

“We still need more parents to find out about it,” she said. “While the school year is six weeks old, we’re still in a process of getting set up.”

Lost hours. Lost generation?

What did this mean for Costa Rican children and youth in 2020?

For the girl whose arms fluttered when she saw her teacher in March 2021, it most likely meant that she didn’t interact with her teachers except for an odd WhatsApp message for eight months of the 2020 school year. Unless she was one of the few families in the shantytown with enough home connectivity to access the MEP’s Teams platform, she filled out paper guides. So did the students in Pacayas and most other rural schools.

In a normal year, assuming a 10-month school year and the lowest instructional time we clocked in 2006, 2.5 hours, this would mean that little girl missed this would mean that that girl missed about 400 hours of school. But, of course, 2020 wasn’t a normal year for any kid on Earth.

Our 2006 second-grader Ariana Monge, whose nephew now attends the prestigious downtown public school she once attended, says her nephew averaged five hours a week of online classes in 2020. Compared to him, those disconnected students missed about 160 hours of instruction and, perhaps more importantly, connection with teachers.

Compared to private school students, according to totals provided by a range of parents, those disconnected students missed out on as many as 960 hours. Given that our 2006 comparison series showed an 88-hour yearly difference between Ariana’s school and Steven’s, these totals boggle the mind.

“How could public schools compete with private schools, though?” one might ask. But we’re not talking quality: just connectivity. And Costa Rica set up a fund in 2009 to close that digital gap.

What’s the best way forward from here? After weeks of reading and hours of interviews, the answer is still not clear. All that’s obvious is that the greatest possible danger is that the sense of urgency around student and school connectivity generated by the COVID-19 crisis disappears before authorities figure it out.

“It’s not just for today. We have to keep preventing (unequal) access as one of the most important inequalities today in terms of the educational support our country needs in the medium and long term,” said MEP Vice Minister Melania Brenes. “Why? Because there are a lot of emergencies in this country,” not just COVID. “We have high-risk areas in rural areas… for rains, landslides, and other issues that affect education services.”

Asked whether the push for equality in connectivity might wane post-COVID, Brenes’s fellow MEP Vice-Minister Paula Villalta said, “Several of us share that worry. We can’t lower our guard just because some students are back in person. Connectivity is a right.”

“This is a national problem,” says Germán Rosales, whose son Fabián attends a private school in San José and received 32.5 hours of virtual instruction per week in 2020. “If we can’t guarantee kids a good general access to technological tools, I think it will be really hard to reduce the gap considering everything that [kids without access] missed last year… and the year before last, during the teachers’ strike.”

Ariel Rodriguez teaches primary-level English classes to adults a the CINDEA in Këkolbi, Talamanca, Limón, in southeastern Costa Rica.

“I studied at the UNED,” he says, referring to the National Distance University. “They loaned tablets to low-income students. It would be interesting for the MEP to do the same thing for elementary and high schools where students need that. It’s not just the virus: there are cases where because of an illness, a pregnancy, students drop out.”

He’s seen just how many factors with the potential to be overcome through a good internet connection end up thwarting the education of young Costa Ricans—because he receives those students, sometimes years later, in his adult classes.

“It would be interesting, and it would be good, so that students don’t miss out on the school year,” he says. “Many, because they have to miss two or three months, leave the whole school year behind.”

A story still unfinished

In the end, a month wasn’t anywhere near long enough to revisit the stories of Greivin, Ariana and Steven. It was like dipping our toes into a vast sea. It was a tantalizing glimpse of steady improvement, years of hard work now endangered by a crisis that, in the words of Paola Vega, “no system was prepared for.”

It was a reminder that even in a country like Costa Rica, justifiably proud of its educational achievements, unjustifiable delays continue to hold students back.

How quickly will the resources enjoyed at Escuela Buenaventura Corrales—newspapers and glue in Ariana’s time, access to Teams in her nephew’s—roll out to prevent long-term effects of the COVID-19 crisis?

How soon will the kinds of reforms the State of Education’s Isabel Román describes, being about the kinds of changes Steven referred to in our 2021 interview, preparing employers instead of employees?

How soon will digital infrastructure match the physical infrastructure that came along for the students who walk in the footsteps of Greivin Cruz?

We never did find him. One potential Greivin Cruz on Facebook never responded; queries in groups and on message boards and over WhatsApp were fruitless. We did verify, using the Civil Registry, that he is alive, and that, while still a teenager, he had a child. A daughter.

Will she go to school in La Carpio? Will she benefit from the new school building and interactive smart boards?

“This situation that’s accumulating places us at risk of a second ‘lost generation,'” says Román, referring to the “lost generation” that was created when many yong people in Costa Rica were excluded from education during the economic crisis of the 1980s. “We could have a generational setbak if we don’t act fast. This country simply can’t afford a new lost generation.”

But the researcher ends with a call to optimism: “This was a stress test in real time that brought out the worst and the best in us,” she said. “These are times of great innovations, and I think that, in effect, we can now see the innovations we’re capable of…

“After the Black Plague, there was a Renaissance.”