We couldn’t close out our February edition, focused on some of the most serious issues that affect the life and death of women in Costa Rica, without exploring the topic of sexual harassment—and for that topic, a natural starting point is the University of Costa Rica. Why the UCR? In the months following the #MeToo movement’s “arrival” in Costa Rica through accusations against ex-President Oscar Arias, the UCR became one more eye of the hurricane. Its main campus in San Pedro and others in the country have borne witness to complaints, claims, protests, and efforts to improve.

Here, María José Cascante, the UCR’s Vice-Rector for Student Life, shares her perspective, which is based on an academic article she is preparing on sexual harassment legislation in Costa Rica.

She asks the question: is the UCR’s experience a success story?

Recently, the University of Costa Rica approved a reform to regulations on sexual harassment. This is an important achievement, a necessary change in the internal regulations of the university. However, it’s worth taking a closer look at it in order to assess the problem, be constructive, and avoid hiding serious problems behind rules and regulations—as so often happens.

The public impact, linked to the media, is part of what has been classified as the “Me Too” movement. In Central America, complaints of rape and sexual harassment were made against current and former presidents, such as Daniel Ortegaof Nicaragua, Jimmy Morales of Guatemala andOscar Arias of Costa Rica. These accusations demonstrated the extent of the problem in Latin America and the degree of impunity that people who engage in harassment, especially those with more power, might have. It also illustrated the weakness of systems that protect misogynistic behavior from leaders.

Although Costa Rica’s legislation on sexual harassment is rather old, when we look at the Central American context, only Panama has approved specific legislation on the subject within the recent past. Guatemala and Nicaragua both have legislation on violence against women. In El Salvador and Honduras, this type of violence is classified within the criminal code; there is no gender-related legislation that specifically addresses the issue.

While Costa Rica does start from strength by having specific legislation on this issue, there are contradictions there: progress of gender issues is not linear, nor is it equal for all citizens.

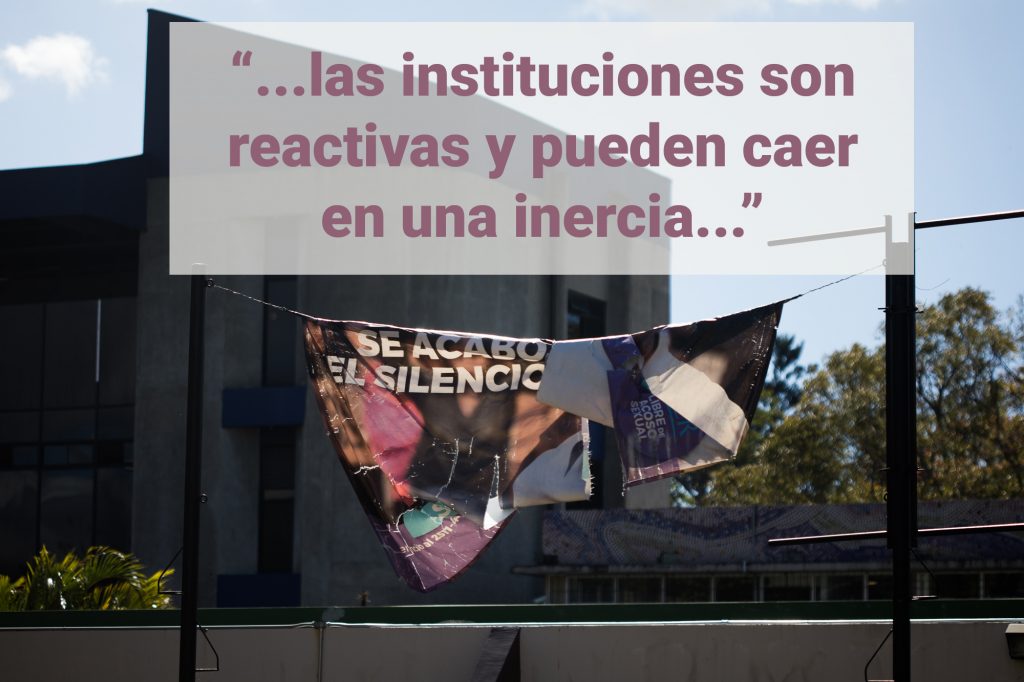

For changes to take place and be effective, the role and influence of organized women’s groups over decision-makers are also relevant. Institutions are reactive and can fall into inertia until pressure is placed on them change and stay up to date, in line with the changing needs of society. These social actors thus become a thermometer that can measure the needs and reforms that regulations require.

Research I’ve conducted show that legislation is a necessary, but not a sufficient, precondition to guarantee the eradication of violence against women. Machismo culture can generate conditions outside of legal norms that make constant review of the issues necessary. In this sense, it is often women’s movements that generate changes and pressure in favor of more and better regulations. It’s not that laws promoting gender equality aren’t important: they’re just not enough.

According to the International Labour Organization, sexual harassment is “unwanted conduct of a sexual nature in the workplace, which makes the person feel offended, humiliated and / or intimidated.” It is a gender problem, since primarily women are the victims of sexual harassment. And according to the National Institute for Women (INAMU), “of the cases handled on site, 97% correspond to women and 3% to men. This last percentage includes men harassed by other men.”

Returning to the case of the UCR: its regulatory reforms took place after a series of public accusations through the media regarding sexual harassment in various schools, faculties, and regional campuses.

In May 2019, a story was published by Semanario Universidad that included reports of sexual harassment experienced by students at the UCR Law School. The story included details about a professor who harassed students and had been sanctioned for sexual harassment in 2015 with the maximum penalty: suspension of eight days from work. After this 2015 sanction, the professor returned to his work, despite the fact that the student body rejected him systematically. The complaints revealed the inability of existing regulations and of previous sanctions to actually prevent future occurrences, since suspension from work was not accompanied by rehabilitation. This, in addition to other limitations on entities’ and authorities’ scope of action.

After this first piece was published, groups of students started demonstrations on the university campus and on social networks. Within public universities, feminist groups such as Me pasó en la UCR (It happened to me at the UCR) used social networks to expand complaints and put pressure on university authorities.

Comments on the case by the dean of the law school were criticized as biased in favor of the professor in question. Later, the dean retracted his statement, apologized, and agreed to investigate the case and take action to raise awareness about the issue within the faculty. These events suggested that authorities do not necessarily possess the awareness needed understand and work on the problem. In this sense, it is not only a problem of harassment, but of a culture of machismo.

Complaints kept surfacing through the media. One of the most serious emerged at the UCR’S Guanacaste Campus. University authorities decided to request an investigation by the Deputy Gender Prosecutor’s Office of the Judicial Investigation Police (OIJ) because the case allegedly involved professors who not only harassed students, but also offered them money for sex. Among those investigated was the campus directory, who was subsequently dismissed at the request of the student body. This second complaint highlighted the seriousness that a situation can attain.

Feminist groups from public universities coordinated their efforts, and, at a press conference with extensive media coverage, declared a “state of emergency” for sexual harassment at public universities. One of the most interesting components of their public denunciation was related to campuses and facilities furthest from the metropolitan area, in areas without a branch of the Institutional Commission Against Sexual Harassment (CICHS) and where the social problems of poverty and unemployment are greater, thus increasing the vulnerability of potential victims.

Various news items about these cases demonstrated that most of students and even civil servants were afraid to present formal complaints. What’s more, the processes for handling complaints are slow and centralized, which discourages complaints. This shows the depth of the problem of sexual harassment: it is as a form of violence that showcases many social inequalities related to gender, socioeconomic status, geographical location and even race. To adequately address the problem and eradicate it, we must include intersectionality in the analysis. When we assume that people have the same experiences at all times, our legislation will have significant gaps.

In general, the UCR’s new regulations attack the most important underlying problems that have been revealed by the cases of sexual harassment at the university and attempts to cover them up. However, it is not a comprehensive reform that seeks to eradicate the culture of machismo that has sought to conceal the harassment of women and others in disadvantaged positions. Nor does the reform include the regional changes that are needed to guarantee that all university campuses are safe for all students. In this respect, it leaves our country’s fundamental contradictions intact.

Good legislation on sexual harassment must take into account capacity for action; it must include a strong institutional framework to sustain it and provide the necessary support to the victims; and it must be decentralized. Likewise, it must include measures for constant review to evaluate whether existing provisions are capable of solving the problem, or if parallel structures are generated that prevent a real solution. It is difficult to establish a time frame for evaluations of legislation. However, it should be part of an institution’s regular planning exercises, which are normally carried out every five years. Likewise, there must be entities in charge of carrying out these reviews and proposing the necessary changes before the problems explode. Such entities must represent the entire population: in this case, the university population.

Finally, legislation is an operational arm that serves to protect women only after they have already become victims. The underlying challenge is to prevent these cases from occurring. This will only be possible through a much-needed cultural change that should be the priority of university authorities with the goal of eradicating all forms of violence against women, including sexual harassment. Both men and women must be included in this process.

This article is a summary of the author’s academic text, “Laws of Sexual Harassment in Costa Rica: from central government to higher education,” which will be published later this year.