Alonso* is 35 years old and the father of two teenage children. He is from San Sebastián, in southern San José. He is sitting in a wheelchair in the administrator’s office of the Nuestra Señora de la Esperanza HIV Home in Cartago. He arrived at this home 10 months ago, in the death with dignity category. Before he entered, members of the Home staff commented that his recovery has been against all prognoses.

He looks nervous, and says clearly that he does not want his image or name to appear in our reporting, but he shares his entire story transparently and openly. Because? Because, according to Alonso, he wants people to have more information about the virus that has affected his life, the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)—the bad, but also the good. (Read more in “Alonso rises”, part of our longform series on the subject.)

Excerpts of our conversation follow, edited for clarity and brevity. His name and certain details have been changed to respect his privacy, at his request and in consideration of the discrimination that people with HIV continue to face.

About three years ago I was diagnosed with this virus. I was also a recovering addict back then, you know what I mean? I spent almost 20 years on drugs.

It was one September when I decided I wanted to spend a sober Christmas. Sometimes I spent Christmas and the 31st waspuff, puff, puff, to evade, to not feel, legal. One day I showed up and told my mother, “Mami, the thing is that I don’t want to use drugs anymore. I just want to enjoy [Christmas] with you, with my children.” She tells me, “Well, that’s fine, but know that what you destroyed for so long, you’re not going to build back it in a day, right?… We’re not going to play around. You’re going to stay in the corredor. You’ll have TV, you’ll have food and everything, but you’re not going to come into the rest of the house.”

The first days were calm, but as the days went by, I thought I was having withdrawal symptoms. I started to get sick. I could no longer tolerate any food or liquid, even water. One day when I was going to take a shower, I looked very thin, and when I turned on the tap I just felt where I disconnected. Everything went black. I started screaming to my mom: “I can’t see. I can’t see.”

She pulled this strength out from inside herself—that strength every mom has—and got me out of there, and sat me down. She said, “It’s ok, pa. Your blood pressure probably dropped. Here, have a glass of hot milk with sugar.”

Several days passed… I began to not be able to swallow, to not digest anything, I began to get thinner and thinner and thinner. I couldn’t speak anymore. They took me to [a clinic] and I spent a lot of hours there… they referred me to the Calderón Guardia and everything was at rock bottom. They diagnosed me with a fungus throughout my body, and two bacteria apart from the fungus, and at that time they told me it was AIDS… The doctor tells me, “We don’t understand how you are alive.”

They sent me to Infectious Diseases. They hospitalized me for 15 days. It was awful, because my feet felt like an elephant’s. I started getting reactions where I was like, “Oh my God, what is this?”

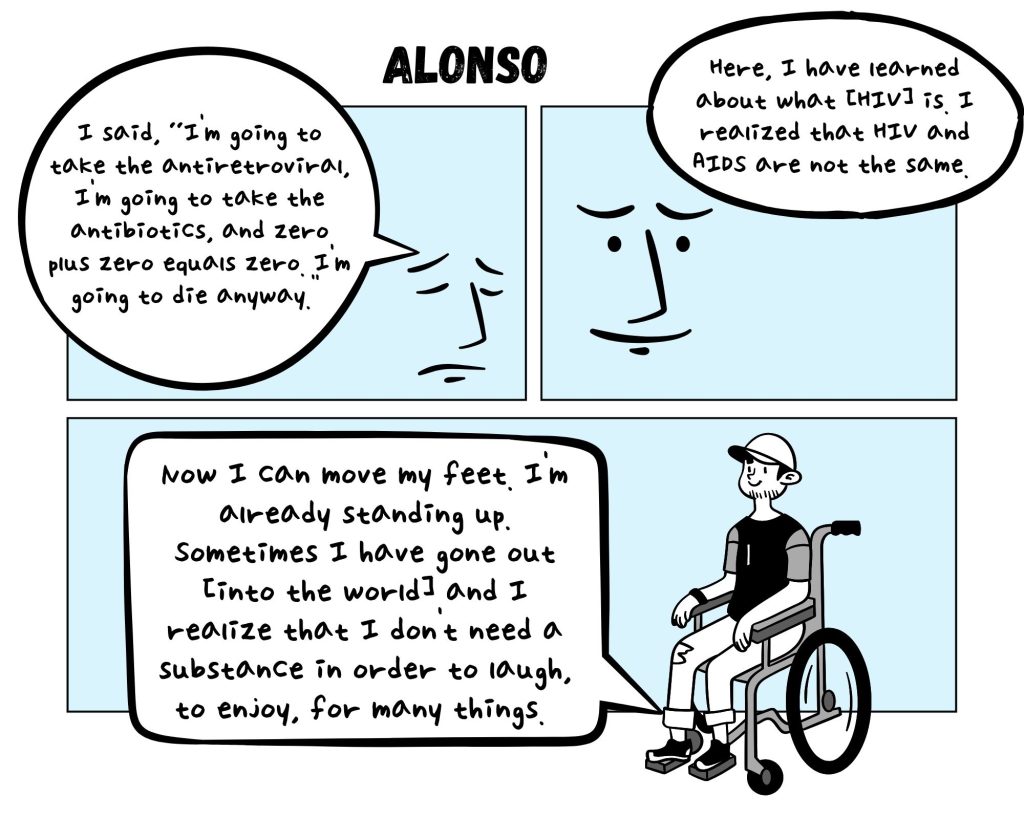

They released me and I was back home, clean, for almost eight months. But every time I went to bed—seriously, an idle mind is the devil’s playground. It was also the lack of information too, you understand me? I said, “I’m going to be taking the antiretroviral, I’m going to take the antibiotics, and zero plus zero equals zero. I’m going to die anyway.”

So I gave myself a little permission.

My children lived my addiction in the flesh. I didn’t leave the neighborhood because I didn’t have the need to leave the neighborhood. I just went out into the streets, and—anyway, qué va.

The first thing they tell you in Infectious Diseases is that… combining drugs with the antiretroviral is a fatal shock. Don’t do it. But in my own ignorance, I was convinced that I was going to die.

I said, “The thing is that I already know how to live on the street. I’ll take my changes again.” Mistake. But that’s where I started. I knew it was a mistake, but I didn’t want to see it. Almost six months passed after I stopped my treatment. I started to feel bad. I was starting to vomit and to have a lot of diarrhea.

One day I said to my mom, ‘I feel bad.’ She said, ‘See? That’s because you stopped your treatment.’ They took me to the Calderón and my viral load was puf, super high. They said, ‘You’re not leaving here. We’re admitting you.’”

I started to feel worse. I tell my mom, “I’m going to pee.” When I went to the bathroom I fell and all I heard was my mom: “What’s wrong, papá? What’s happening?”

They lifted me up and sat me in a wheelchair. They say that I was in a coma for 22 days. I had a tracheotomy. When I woke up, I was very thirsty and I wanted a bottle of water. But they told me, “No, you can’t.” Why me? I could still speak, but his throat was blocked. And I wanted to get up and I can’t feel anything from the waist down.

From that moment I didn’t want to live anymore. I gave up… Karma got me. Karma exists. What you do, comes back to you.

From there, I spent almost three months in bed. Bath in bed, everything in bed—horrible. I was crying because I couldn’t feel my legs. I wanted to lift them up and I couldn’t. I wanted to lie face down: I couldn’t. I wanted to eat: I couldn’t. Until there came a time when they stuck a tube up my nose—oh, my God! Legal, these last two years have been the bitterest of my life.

My birthday is September 7th. They let me out on September 8th. I wanted to at least enjoy it on the outside, my 35th birthday. They educated my mom and everything. My mom got me a special bed for me, a wheelchair for me. Even so, I got very sick at home again, and they hospitalized me again.

As time passed, they came to talk to me about this place [the Home]. Sometimes I thank God that perhaps an angel appeared. They asked me if I wanted an opportunity, and I didn’t think twice.

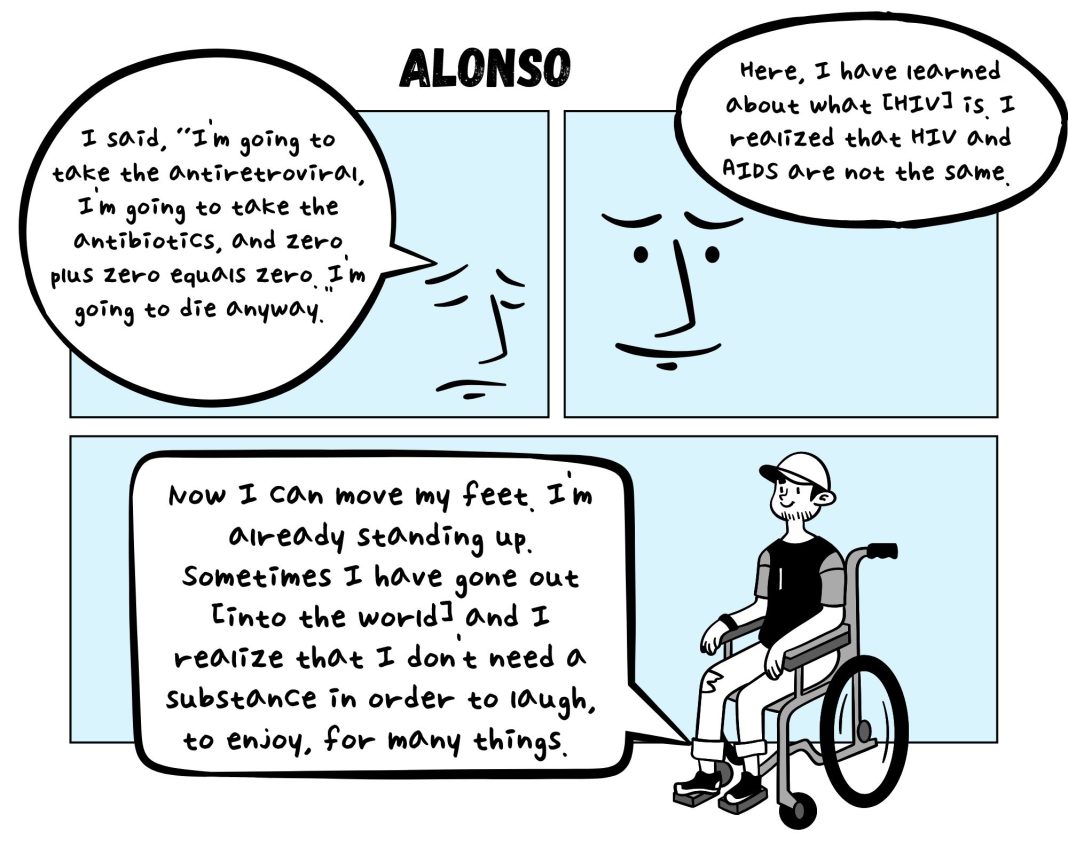

I was eager to leave the hospital, no matter where I was going—just not a hospital, because many people were dying in there beside me. They tell me now that I came here for “death with dignity.” Imagine what state I was in. In a wheelchair, wearing a catheter, using a diaper, legal, because I had lost all sensitivity in my sphincter—but thank God that a place like this exists. Here, I have learned about what [HIV] is. I realized that HIV and AIDS are not the same. I have also realized that I cannot abandon my treatment.

I’m coming up on 10 months in the home. Now I can move my feet. I’m already standing up. Sometimes I have gone out [into the world] and I realize that I don’t need a substance in order to laugh, to enjoy, for many things. I know that being here is temporary, but I also have to develop patience and perseverance to reach at least my walking distance. One step at a time. I don’t rush. I don’t want to run without having first learned to crawl.

[The other version of me, during addiction] did many things that only God knows. I got to know places I shouldn’t have seen, see things I shouldn’t have seen. But today, thank God, I’m here.

If I visualize myself regarding my goals, I want to at least walk again. Find an inclusive place where I’m accepted, such as a place to work where I wouldn’t have to stand for long periods of time. And try to be happy. Love myself more. I feel proud of myself.

My children are already grown: 15 and 14 years old. Maybe I have never been there for them, but perhaps God is giving me another opportunity—now, in this stage of rebellious preadolescence—to show up with more foundations to at least guide them. “Don’t do what Dad did. He was doing well, and then he took a detour and went into the ravine.”

We have to realize that HIV is a 21st century disease. Don’t you understand that it is growing stronger? We know what tuberculosis is—what this, that and the other is. Maybe we should stop seeing HIV as something small that doesn’t get as much attention as other diseases.

We know that the person does not die from HIV: the person dies from the opportunistic diseases that occur. [You have to] keep the CD4 high, with good nutrition and hygiene, good sleep. And good mental health. We can’t let ourselves be set off by any little thing, because we also know that mental health plays a very important role [in supporting] CD4.

I often thank God for giving me HIV, because it was maybe the only way for me to say no to drugs for once and for all. I used to ask myself, “¿Why, papá?” But here [at the Home], I changed the question: “What are you here to do?”

*Alonso’s real name has been withheld at his request, to protect his privacy and in consideration of the discrimination faced by people with HIV in Costa Rica. Learn more about HIV Hogar Nuestra Señora de la Esperanza at their Facebook page, contact by email, or donate via SINPE Móvil at 8507-7676.