Miguel is 46 years old, and he is very aware of that fact. He’s asked, what gives you confidence that you will be able to maintain your newfound stability, if you’ve never been able to before? Because he doesn’t have any more time, he says with a laugh: “I’m practically a senior citizen.”

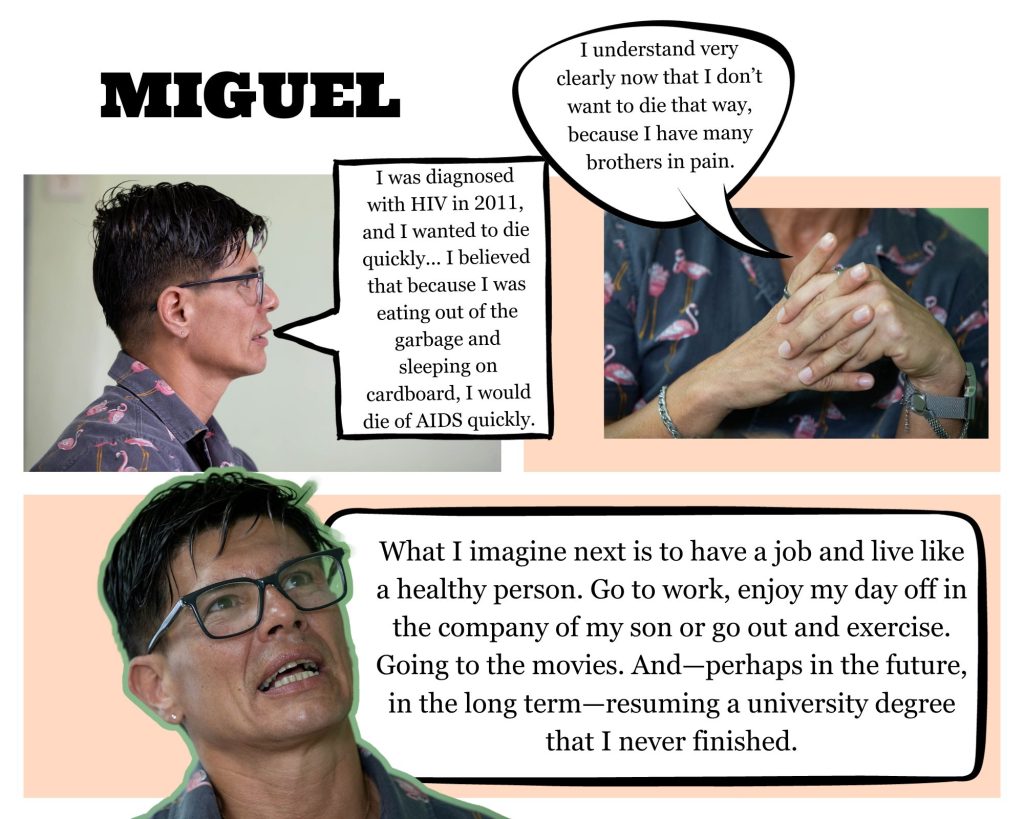

After decades marked by his addiction, a life on the streets, and stints in multiple prisons, in addition to his diagnosis with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Miguel says that these days, his fondest hope is to spend time with his 30-year-old son. He gave us permission to use his real name, as well as his image. He speaks directly and openly about the darkest times in his life.

We spoke in July, at the Nuestra Señora de la Esperanza HIV Home in Cartago. (Read more in “Miguel decides to live”, part of our chronicle on this topic). Excerpts follow, edited for clarity and brevity.

I started experimenting with drugs when I was 14 or 15 years old. I have chronic substance abuse, and so I’ve been institutionalized most of my life. I have been to many drug [rehabilitation] institutions. I was in several prisons, and I have been in the Zona Roja [the so-called Red Zone or red-light district] of San José for a long time.

I am from Desamparados, and there are lots of places where drugs are consumed and sold in Desamparados, but I did not want my son to see me that way, in the condition I was in. I didn’t want to come out of a bunker for using drugs, and maybe at that moment [my son] would be passing by. So I went to the Zona Roja. I said, “[My relatives] won’t see me here, because they never come here, so here I’m going to feel more comfortable messing up my life.”

I was diagnosed with HIV in 2011, and I wanted to die quickly. I had many prejudices and a lot of bad information regarding HIV, so I believed that because I was eating out of the garbage, because I was sleeping on cardboard, I would die of AIDS [acquired immunodeficiency syndrome] very quickly—and that was exactly what I wanted. But then one day I got sick with tuberculosis and was hospitalized. It was a very painful and bitter experience.

It is very easy to say “I want to get sick and die,” but when I was in the hospital, I realized all the suffering, everything I had to go through because I was there. Just to go to the bathroom, I had to think about it first for half an hour. I got scared and said, “No, I think so. I don’t want to get sick with AIDS and die that way.”

I was able to recover from tuberculosis. I was able to start implementing a healthy lifestyle again. I went back to living on the street, due to my chronic history of drug use—but I was already very clear that I did not want to die that way. I was very scared. I have learned that perhaps I do not have the necessary psycho-emotional tools to be able to face many life situations that all human beings face, such as a partner leaving us, a family member dying, or being fired from a job. I feel that I have a certain deficiency in that sense, compared to other people. Because of that deficiency, I return to the Zona Roja, I fall back into drugs. I am homeless. Physically, I had deteriorated significantly.

The last time I was in those conditions was approximately three months ago. I am very clear that I do not want to die that way, because I know many brothers in pain—addicts who are on the streets, but who have made peace with that lifestyle. They have said, “I live like this. I eat garbage. I know when they are going to pick up scrap metal, and where I am going to go to sell it to the scrap yard.” But I have said to myself, “No. I don’t want to live like this. I want to live on this side—the side of society.”

I want to be a functional person. I want to be a person with the necessary emotional skills to be able to face the bad news that life gives us to all of us. That is what I want.

Then I learned from the social workers at the San Juan de Dios [Hospital] about this place, Nuestra Señora de la Esperanza. I spent a month waiting on the street to be able to enter here, because it was Holy Week, and the Board of Directors had to meet to approve my entry. It was another month that I spent on the streets messing up my life, until I had the opportunity to enter this home.

It was worth the wait, because this home has an excellent team—professionals who are helping me focus on acquiring these tools that will allow me to have a successful social reintegration. That’s my goal.

It is possible that I will fall back into the patterns that have been the trend during my entire life. I hope not. I’m not losing hold of that hope.

It’s not just about adherence to pharmacological treatment, which is essential for people with health conditions like ours. There are other factors such as leading healthy lifestyles, sleeping well, eating well, exercising, finding healthy hobbies that I can have fun with. When I was young, I had the mistaken idea that having fun meant going out to a club, drinking beers, smoking marijuana, sniffing cocaine, having sex. Now there are other things that I can also do to have fun.

My son is a chef. I would very much like to be able to spend time with him and invite him to dinner, or prepare a meal in the kitchen with him. That would be so much fun, because at some other moment in my life I would have said, “How boring is this? How boring to be in a kitchen cooking, chopping.”

I would like to have fun with these little things, and not reach those points of climax that I was looking for all my life. Those brought me only self-destruction.

I received my diagnosis at the Marcial Fallas Clinic in Desamparados. I went in to take tests because I wanted to. I knew he had made a lot of mistakes on the street, so I wanted to know how I was doing. I tested positive for HIV, and for syphilis. But the HIV diagnosis was especially shocking—I think that it wasn’t because of the news itself, because now you take medication and you can cope with life like any other person. It was more than that. It was because of all the prejudices that I had about it. All this stigma around HIV and homosexuals: it is a punishment from God. They can no longer kiss. They cannot share all these things.

I had an ex-boyfriend who is a doctor… I ran into him in the hallways by chance. “Hello Miguel, how are you? What’s the matter? You don’t look so good.” “I was diagnosed with HIV.” Then he tells me, “Come into the office. Let’s talk.” I am so grateful to him, because he told me, “Look, Miguel. Today, HIV is a disease you can live by taking your medication. You can live for years.” I was so grateful to him for that conversation.

But then when I started using drugs again, I said, “Well, no. Since I am not taking treatment of any kind, perhaps eating from the garbage and sleeping on cardboard, some bacteria or some opportunistic disease is going to come and end my life.” I had a self-destructive and suicidal idea of what HIV could do to me. I was disgusted. When they gave me the news, I was disgusted with my body. If I got cut, I was disgusted bymy blood. I was disgusted by my saliva. I didn’t want to touch anyone, I didn’t want to hug my son, I didn’t want to shake his hand.

I was full of shame. I was full of guilt. I was full of a lot of feelings that led me to depression.

[Later] I met a boy… who told me that he has HIV. He told me so naturally, with so much courage. I felt ashamed that I didn’t have the same courage, that I couldn’t say it like that—so honestly, so transparently. He told me, “It’s your decision whether or not you are willing to accept me.” So I told him, “Well, I have news for you. I have HIV, too.” Since that moment, I’ve learned that I should not feel ashamed, nor should I feel afraid to tell others: This is my condition.

[We asked Miguel what he would do if he had a blank check and the power to do anything he wants to improve the lives of people with HIV in Costa Rica.] Education is what’s most lacking. At one point I was living with my parents. They knew my diagnosis, and so they told me, “You’re going to use these utensils only.” A little nephew lived with us, and they’d say, “We’ll thank you not to pick him up, not to give him kisses,” when it’s a child I love with all my heart, a child I wanted to shower with hugs and kisses.

One day I heard a friend [with HIV] say, ‘I don’t want to spend time with my kids, because I don’t want them to get what I have.’ How painful that he himself has this prejudice! [Eliminating] that ignorance is what I’d want to buy, if I had that blank check.

I think that having HIV has actually helped me in certain circumstances. I come from a super dysfunctional family; I myself am super dysfunctional. Then I went to prison, and in prison there is a great violation of human rights… but the penal system gives special attention to people who have HIV, and I think that helped me improve my conditions a little. If it had not been for this, I may not have had access to many benefits that I had access to in prison. If it hadn’t been for [HIV], I never would have made it here. I would have been just another addict. Just another person on the street. In some ways, it’s like saying, ‘Good thing I have HIV.’”

When I first came to the Nuestra Señora de la Esperanza Home, I showed up only with the clothes on my back, with my pants full of shit and smelly shoes. Here, they gave me shoes. They took me to have my teeth fixed. They took me to get eyeglasses so I could read, so I love to read. Now I’m looking for work.

What I imagine next is to have a job and live like a healthy person. Go to work, enjoy my day off in the company of my son or go out and exercise. Going to the movies. And—perhaps in the future, in the long term—resuming a university degree that I never finished. I was studying psychology.

As a person who used psychoactive substances, every time I started using again, I had a catastrophic idea that all was lost. But now, looking back, I think all was not lost. These have all been teachings for me… I lock myself in my egocentrism. I believe myself to be all-powerful and I don’t look for help. That has been a factor that has led me to relapse into these patterns. But this time I don’t believe in that dialogue of “I can do everything,” but rather that other people can also help me.

Before, I used to say: “I have so much time ahead of me. I’m so young. The world is my oyster.” Not anymore. I’m all grown up. I think it’s time. It’s time now.

Learn more about HIV Hogar Nuestra Señora de la Esperanza at their Facebook page, contact by email, or donate via SINPE Móvil at 8507-7676.