El Colectivo 506 has brought us into contact with many new friends, but it’s also started fresh conversations with familiar faces. Such is the case of Heidi Romanish, a faithful reader and Annual Member who lived in Costa Rica for 14 years and, now back in her home state of Minnesota, is a proud mom to a Costa Rican-U.S. daughter, Emilia.

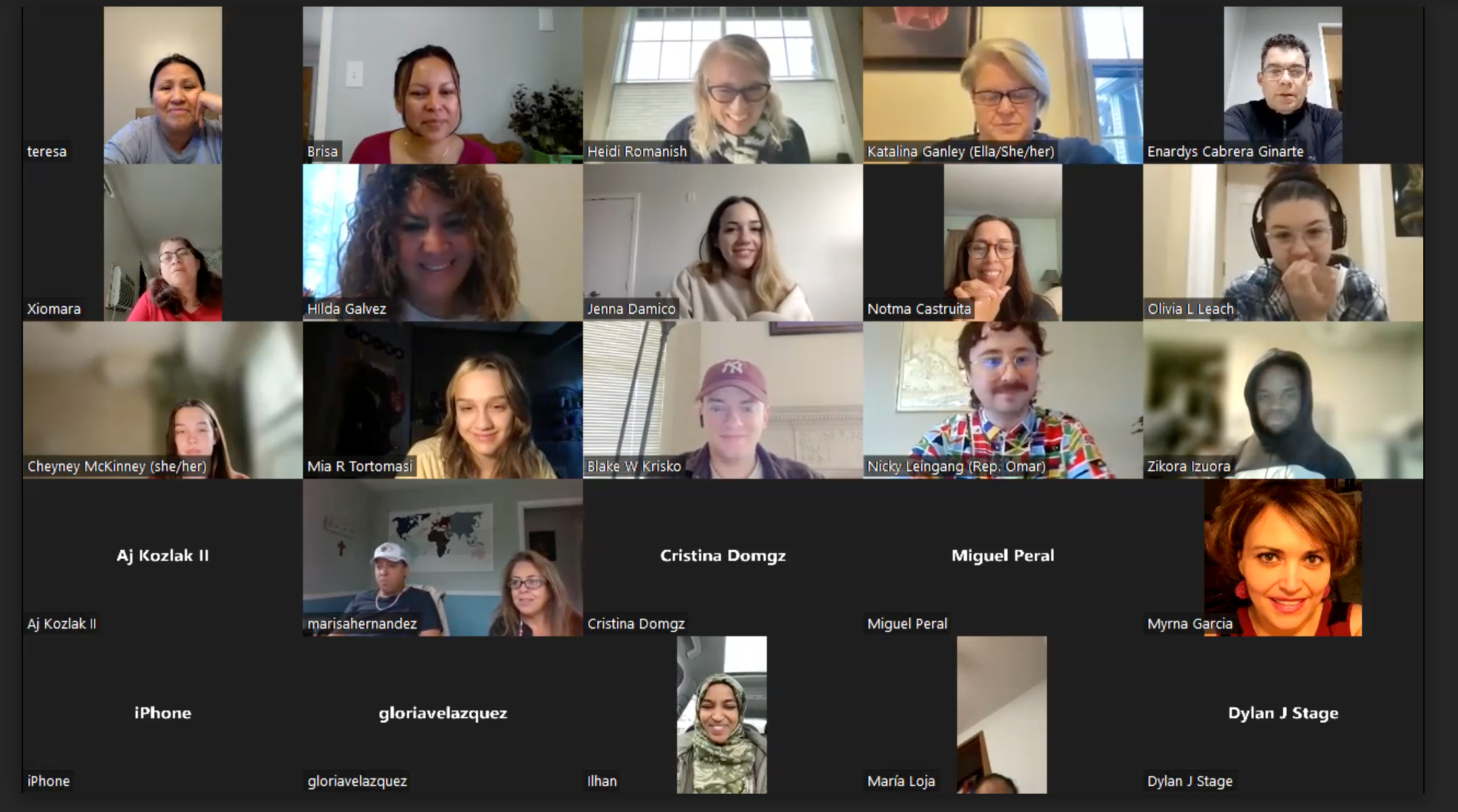

Heidi is a staunch advocate for the rights of immigrants. She works as a legal assistant as well as a medical and community interpreter, and she teaches citizenship class through a partnership between the Latino Youth Development Collaborative and the University of Minnesota. The class recently hosted U.S. Representative Ilhan Omar as a guest speaker.

We talked to Heidi about some of the key issues that have driven her career and activism, and how her time in Costa Rica shaped those passions; we walked away dreaming of a 2023 edition of El Colectivo 506 focused on people on the pathway to Costa Rican citizenship. Excerpts follow.

You’ve focused so much of your professional life on work to promote equity and justice. How much of that do you think you brought to your experiences in Costa Rica, and what did you take away that changed you?

What I carried to Costa Rica with me were women’s studies, feminism… and health care. I was lobbying for a single payer bill in Minnesota, with grassroots organizing. So then it was like, “Oh, wow, I live in a country now with single payer, national health care.” It was like seeing everything we’d been talking about, coming to life. For example, [we’d always said] that if we have universal health care, the private insurers are not going to go away. People are always going to be able to get a higher level of care. The rich are always going to be able to pay more. But what you’re doing is guaranteeing this basic level of care for everyone.

I remember when Emilia got her vaccines, going to the EBAIS and getting the little cardboard tags for waiting in line. It was just so simple. How do you keep costs down in health care? You walk to a little clinic, get a little construction paper number, your child gets vaccines. You’re on your way.

I do feel that over the years [in Costa Rica], I lost a lot of the feminism. I accepted that abortion was not a right I had there. In the beginning, the catcalls and the objectification of women made my blood boil; by the end, I was just, like, laughing along with everyone else—maybe not laughing, but you become desensitized to it. Then there’s the whole motherhood thing, becoming this revered mother in such a different way than in the United States. But [since returning home] I’ve definitely gotten back to more my feminist roots, like a rubber band.

How did the experience affect your view of immigration?

Seeing the policies there related to immigration… I took all that with me, and it is my present life. Understanding that if you have money, you can go visit. If you don’t, you can’t. I guess I came back to the United States saying: ok, after seeing the US from Costa Rica, now I need to go back now and do my part to change it.

With the immigration work we do now, we say, “We’re the ones who built this.” Dismantling ICE, ending the detention system—it’s really hard for immigrants to be at the forefront of that fight. They do have to lead it in a lot of ways because they’re the affected ones, but at the same time, we’re the ones who built it so we can take it apart.

Living here, you do gain a much greater appreciation for how the systems that we have built in the United States affect so far beyond us. The Biden administration makes changes to policies that affect Venezuelan refugees, and you see it on the streets in a country like Costa Rica—let alone the countries that are actually in crisis. For people who aren’t immersed in this topic the way you are, what do you think is the beginner’s guide to learning about this?

When I got down to Costa Rica, I think the beginner’s guide was learning about those tourist visas, how it works. People applying for the visas, demonstrating how much money they have and this idea that they’re not going to stay, and understanding that others bypass all that, head out on foot and cross deserts. You can’t quell human migration… The citizenship class I teach is kind of the last hurdle to climb in that process.

Tell me about the class.

It’s pretty awesome. We work with the 100 Questions [the basic study guide for the naturalization exam], but we’re also trying to explore what it means to get involved and participate. Yeah, you’re going to have this great right to vote, but it’s more than that.

And memorizing that material isn’t the hardest part of it. The hardest part is dealing with the immigration official. “Have you ever been a terrorist? Have you ever been a communist? Have you ever not paid your taxes?”… People just get in there with that immigration official and they can know every single question about the Stars and Stripes, but they freeze. So we make it really interactive, really fun.

We work with University of Minnesota students, who are the tutors… The class is on Saturdays, but the tutors work one-on-one during the week. They’re working on their Spanish, and the people taking the citizenship test are working on their English. But who’s most changed at the end? All the U of M kids. A lot of these tutors… go on to do stuff with immigration and want to change the system.

What would you like to see from journalists when dealing with immigration topics—where you are, or in Costa Rica, or anywhere?

I think the true story about it all would be what happens even when you’re not a citizen, and you’re living in another country. You can be, and should be, active in the community, making changes that you want to see. You don’t need that official status to do all the other things up to voting. It’s the difference between living in the shadows and becoming an active participant in the community.

There’s this emphasis on citizenship, like, “We need more voters,” and people become numbers. But actually, they were already contributing in all these different ways. I think the untold story is like what El Colectivo 506 does, telling the story of people’s lives—and how they’ve become the fabric of a community and a country.