Talking about Chirripó National Park always involves some numbers. The best known are 3,821, the number of meters above sea level of the towering peak of Cerro Chirripó, Costa Rica’s highest peak (that’s 122,536 feet); and 14.5, the length in kilometers of the best-known and most traveled path to enter the park, which leads to the shelter at Crestones Base Camp.

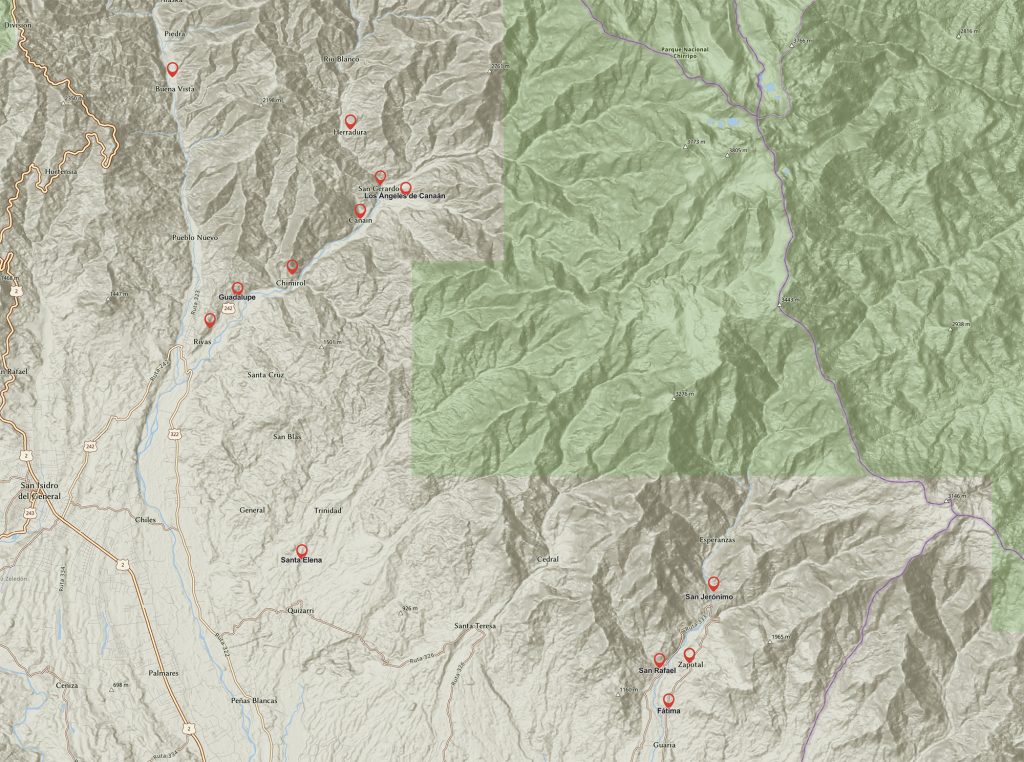

But there are other less known numbers that are perhaps more important, such as 80 and 70. Those are percentages of Costa Rica’s and Central America’s páramo vegetation that this national park protects, making Chirripó the leading guardian of rare high plateau ecosystems. Five: the number of river basins that originate in this protected area, one draining towards the Pacific and four towards the Atlantic. And 13, the number of rural communities that benefit from and contribute to the park.

When Chirripó National Park was founded in 1975, some of the neighboring communities began to see a change in their relationship with the mountain, especially as tourism to Chirripó began to grow.

“My father was a hunter who knew the mountain by heart. They were never going to catch him,” says David Arias, president of the Chirripó Association of Muleteers, Porters and Cooks, about his father Jorge Luis Arias, one of the association’s founders. David remembers national park authorities’ success in creating agreements with the inhabitants of Rivas, building a relationship between the park and the community that generated much more than the protection of flora and fauna. “My father tells me: ‘I no longer had to go to kill a peccary to bring meat to the house. Now I had [another] resource. It was better to go and buy two kilos of [pork] and make some chicharrones.”

However, at the beginning of the new century, Chirripó’s communities and authorities found themselves facing the same questions that arise in other protected areas of Costa Rica: How can neighboring communities generate more income, and how can that income be distributed more equitably? How can the community be more involved to ease the conservation burden on rangers, who always face limited budgets?

The solutions that have been tested on this mountain helped formulate answers to these questions. However, achieving them has been the administrative equivalent of reaching the top of an iconic mountain. They are based on two legal figures: the Non-Essential Services Concession, and the Usage Permit.

One concession, seven years waiting, seven years trying

The Non-Essential Services Concession is a relatively new public procurement figure in Costa Rica. According to Laura Díaz, administrator of the Chirripó PN since October 2018, it is an administrative contract allowed under Costa Rica’s Biodiversity Law. It grants the concessionaire the ability to use infrastructure such as buildings, parking lots, and shelters within a protected area in order to provide a service to a third party—tourists, in the case of Chirripó National Park. In this type of contract, the requirements are structured in a way that gives priority to organizations from the communities that surround the park.

In other words, while community organizations surrounding Chirripó already provided services individually—such as carrying luggage, renting equipment, or occasional food preparation at Crestones Base Camp—the concession would allow them to do it as a group of organizations and on a permanent basis. It would also allow them to include other services, such as lodging in hostel rooms and stores.

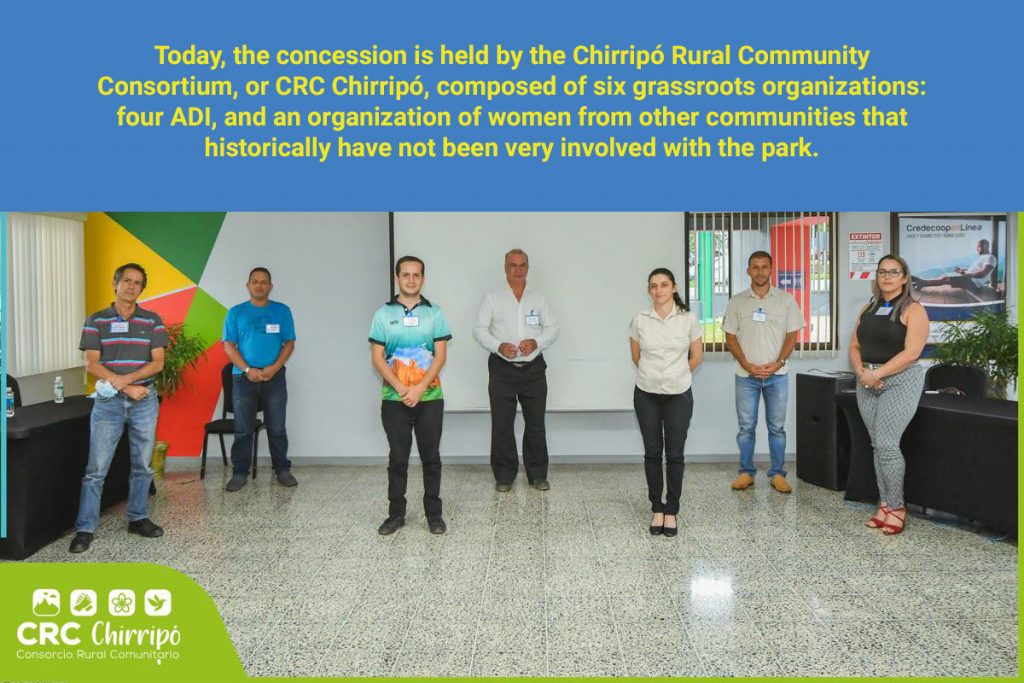

In 2007, these communities became a national laboratory for the first concession of non-essential services in a national park, facilitated by the positive relationship that already existed between communities and PNChirripó, and the historical practice of providing services to the visitors. However, it would take many years to achieve, including three tender attempts and two union entities.

“It was a big fight to reach that goal,” says Juan Carlos Ureña, current president of San Gerardo’s Integral Development Association, or ADI. “The community saw it as a threat, because people were very concerned that prices would go up and visitors would not come.”

“Both we as officials and the community had to understand what a concession was,” says Laura. “Not even SINAC was very clear about what a non-essential service concession is.”

At the end of 2013, a concession was awarded for the main entrance route to the park, which began operation in 2014. For almost six years, the concession was held by the Eternal Waters Consortium, which was made up of the ADI of San Gerardo; the Association of Muleteers, Porters and Cooks of Chirripó; and the Chirripó Community Rural Tourism Chamber (CATURCOCHI).

According to Omar Elizondo, president of CATURCOCHI, an organization that has been part of both concessionaires at PNChirripó, a consortium is a contractual figure that “unites companies or organizations that sign a solidarity commitment to participate” in a public tender for non-essential services. This solidarity commitment means, among other things, that the consortium will provide the services hired by the state even if one or more parties leave the consortium, and that profits will be used to support community development.

“It is the option with the most complex logistics,” adds Omar. This type of union of organizations and companies not only requires extensive coordination, but also involves, in the case of PNChirripó, managing the equivalent of five companies. “There is no margin for error. Any mistake you make puts the concession at risk.”

The consortium is constantly supervised by the administration of PNChirripó. Every three months, the services are reviewed following a strict form.

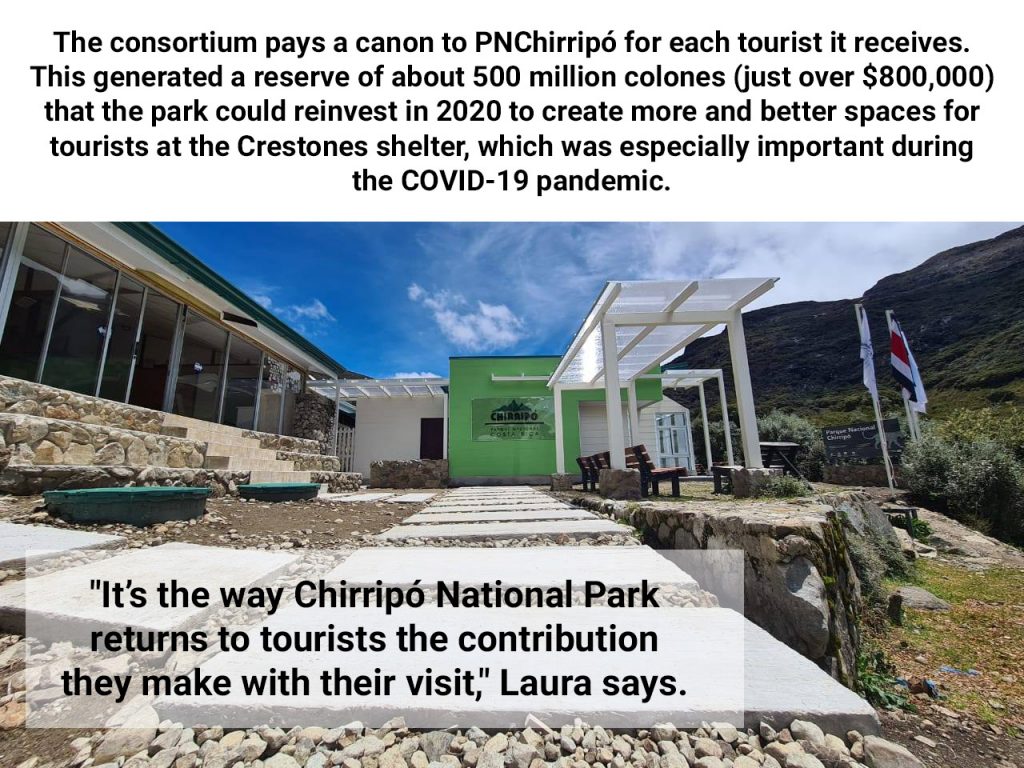

The concession has had a positive impact on both the communities and the officials of the National System of Conservation Areas (SINAC) who are responsible for the park.

“Now it is the community that receives [the tourist] and provides them with services,” says Laura, “but in each of these organizations, we are instilling the idea that with the concession, not only can we make money, but we can also conserve. We have communities that are more attentive, more committed to the environment.”

The concession has freed park rangers from many of the tasks they had to perform before — such as solid and organic waste management at Base Crestones—and they have been able to spend more time working with the communities and on conservation tasks.

Three usage permits

In addition to the concession, there is another tool that allows the communities near Chirripó to generate an income thanks to the protected area. ADI San Gerardo, ADI Herradura and ATURENA are the three organizations that have a Usage Permit within the Chirripó PN.

A usage permit, Laura explains, is a power granted by the Forestry Law to each Conservation Area (AC) to allow the use of the state’s natural heritage. There are three types of use: research, training, and ecotourism. The latter involves activities such as hiking, rappelling, canopy, and others.

In PNChirripó, the usage permits allow organizations to offer guide services on the three entry routes to Chirripó, and carry luggage on two of the three.

According to Alexis, the president of ATURENA, obtaining a usage permit is “very complicated.” It seems to be a matter of trust and good relations, since each AC studies at the local level whether the organizations applying for the permit can become strategic park partners in this way.

For Alexis and colleagues in other organizations, the main advantage of these relationships is that the organizations work together to take care of the park.

Blaine Villareiva, president of the ADI Herradura Tourism Committee, spoke with El Colectivo 506 by phone from Paso de los Indios. Along with the group of tourists that he was taking to the top, he was resting for the evening at a temperature of 8℃.

“We help to maintain surveillance on the trail, help with conservation, report any anomalies or illegal tourism on the trail, do trail maintenance,” he says. “We offer a brigade of forest firefighters in case of an emergency and a brigade for emergency support within the park.”

“Now we have a 25-person brigade [for forest firefighting], and we are working to amass all the personal equipment by our own means,” says David from the San Gerardo Muleteers Association.

“You can see the commitment of these communities. If there is a fire, they take care of it immediately,” says Laura the benefits of the usage permits. In view of the current budget cuts faced by SINAC, these organizations also offer transportation to SINAC personnel so that they do not have to incur expenses, and they’re actively participating in the Natural Resources Surveillance Committees (COVIRENAS). These are defined by SINAC on its website as “are groups of people from civil society who have organized to help monitor and protect natural resources.” (Read a column about COVIRENAS from our April issue, here.)

“The message I receive from them is, ‘Nothing can stop us,’” says Laura.

The usage permits have also been essential in supporting the iconic Cerro Chirripó Mountain Race, which in December 2021 will take place for the 32nd time, and which has recently been certified by the International Skyrunning Federation.

Organized by the ADI of San Gerardo, the race is the only one in Costa Rica that takes place in a protected area. Almost 500 runners participate in its 12 and 34 km categories; over the course of three hours, they ascend to Base Crestones and return to San Gerardo. This race—in addition to promoting the area, generating value chains, and raising funds through sponsorships and activities that are primarily reinvested in road maintenance—has become a tool to promote conservation.

“Two weeks beforehand, workshops are held to motivate the conservation among children in the community,” says Juan Carlos. “We use the race as a platform to start the campaign against forest fires.”

Tres retos

Although the concession and usage permits have helped foster a strong relationship between all these communities and the park, and the positive effects of these changes are tangible, the relationships also face challenges.

“Our dependence on SINAC to operate the project [is a limitation] because we can’t sell tickets,” says Omar. This has worsened during the pandemic, which has forced SINAC to organize park visitors into social bubbles. In 2016, Chirripó became Costa Rica’s first national park to switch to online reservations and purchases, but according to the park administrator, this year they have been forced to return phone reservations, which is slow.

Juan Carlos, president of the ADI of San Gerardo, recommends that future consortia invest in leadership and business training for the participants. He adds that it is important for people to understand that a consortium “is a communal company and a social company.”

The 2020 concessionaire change occurred after an internal breakdown in the Eternal Waters Consortium. The park administration’s response to this conflict was to suggest to the organizations that they seek support from conflict management professionals, who in turn suggested that decisions be made in an assembly of members and not just by their leaders. But the consortium dissolved, and two new consortia competed for the award.

Operations continued under the new consortium, but the change left many wounds in the communities. Laura remembers meeting people who were practically in tears because they thought they would no longer be able to work in the park.

All the organizations involved with the park continue to reinvent themselves. However, it was evident in the interviews carried out by El Colectivo 506 that the communities continue to suffer the consequences of a difference of opinion regarding company management—a turn of events generated significant resentment.

“The administration also works to make sure that the trust and the agenda that we’ve had since 1975 is not lost,” says Laura about helping to heal the grievances. “These organizations are very important for the park, for everything they have worked for.”

Three ingredients for success

“Many colleagues [at SINAC] ask me, is it our role to promote these participation mechanisms?” says Laura, the administrator. Her answer? Affirmative. “If the conservation area does not develop these participation mechanisms with strategic allies, the story would be different. We might have enemies, and the task [of reducing threats] would never end.”

But according to all those interviewed, the success of the relationship between these communities and PNChirripó goes beyond the availability and openness of SINAC and its workers towards promoting these relationships. Everyone said the same thing: the most important step is to cultivate trust between all parties, a trust that must transcend individuals and be part of the essence of institutions and organizations.

“Before taking this bull by the horns, you have to know what it’s about,” says Omar, who has participated in both concessions and consortia. “We had to suffer a lot in the previous process.” For this reason, he says it’s to achieve consensus among community organizations, to reduce differences and internal competition between groups and leaders.

For David, from San Gerardo, the community’s sense of belonging to the park is very important, and it increases when the park generates benefits for the community: “If people do not understand that to receive, we also have to contribute willingly, it is very difficult to build a lasting relationship.”

“There has to be a lot of availability from community members and leaders regarding conservation,” says Alexis, from San Jerónimo, echoing a common refrain.

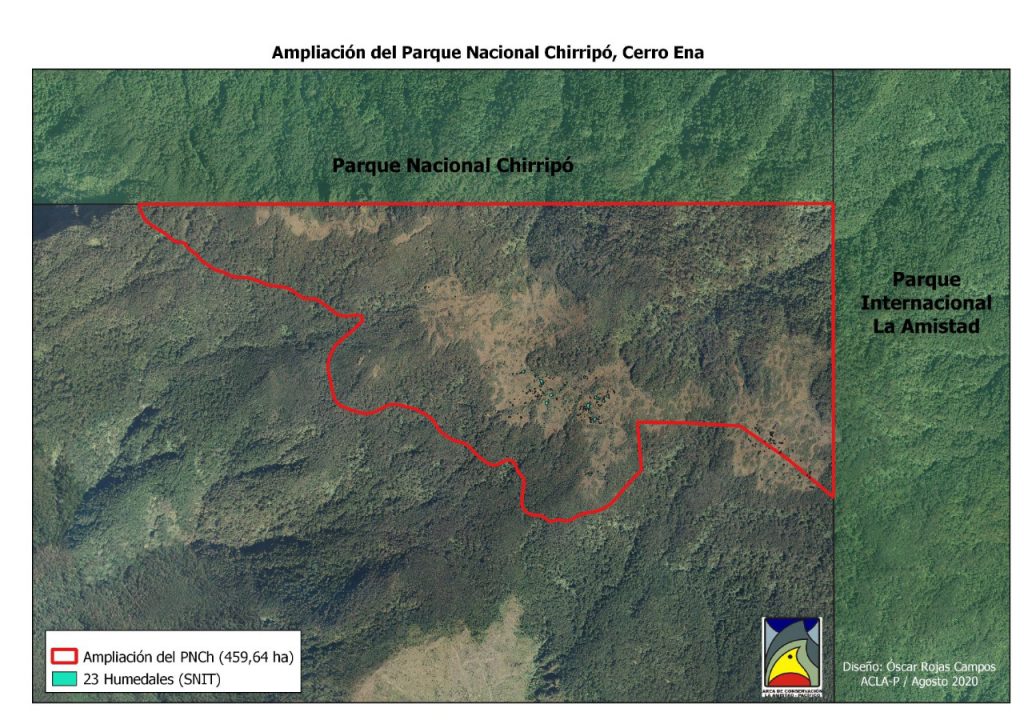

At press time, PNChirripó is about to grow once again: not only in terms of sustainability and organizations, but also in terms of land.

The president of ATURENA told El Colectivo 506 that on August 18th, the incorporation of Cerro Ena to PNChirripó will be formalized, and the official signature of this change will be part of the celebrations of National Parks Day on August 24th. This action will add 459.64 hectares of mountain land at more than 3,000 meters above sea level—which, in any case, is the state’s patrimony—to PNChirripó’s current 50,150 hectares.

“We are the organization that promoted this process,” said Alexis. “We could have said, ‘We are going to take ownership of this and we are not going to let anyone in.’ But no. We want to protect it in a better way.”

—-

Next Thursday: Explore the three access routes to Chirripó, the communities that operate them, and how you can visit them in one of our very first Tips 506.