Third in a four-part series on Costa Rica’s fight against fake news.

Several months into the COVID-19 pandemic, Helen Naranjo noticed that something funny was happening in her home region of Los Santos.

It’s a land of dramatic mountains, near-vertical coffee fields, and—thanks in large part to the world-renowned coffee industry that drives the valley—more than 50,000 people in three municipalities, Dota, Tarrazú, and León Cortés. While the region is under two hours from San José, just up the Cerro de la Muerte from the eastern edge of the Central Valley, it feels a world away. Information sometimes takes a little longer to arrive, and so did COVID-19. The region was among the country’s last to report cases of the disease at the start of the pandemic.

But in 2021, the numbers were changing, and Helen was quick to pick up on distortion in the way they were being discussed in the towns of the valley. In her multiple roles as a daughter of Los Santos, the new founder of the area’s first independent digital media organization, and a former community leader, Helen was in infinite WhatsApp groups both local and national. After years away from home in San José to studying journalism and then working for national media such as the public news station, Channel 13—mixed with a stint as the vice-mayor of Tarrazú—Helen headed back to Los Santos in 2020 and founded her own news organization, Los Santos Digital.

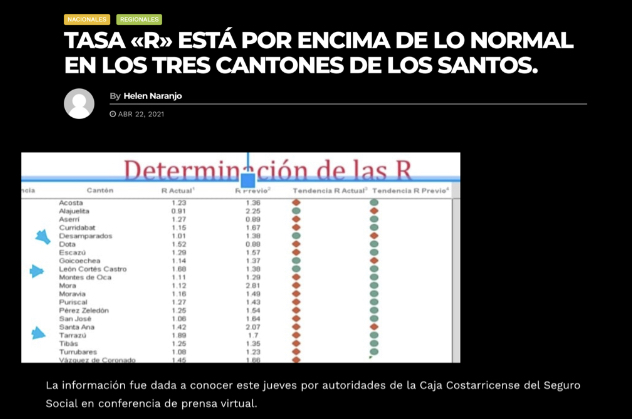

From that position, she noticed that information that had been shared by a University of Costa Rica researcher about the “tasa R” or R number of Los Santos communities—the average number of people each person with a disease, in this case COVID-19, goes on to infect—was blowing up in local groups and being shared incorrectly.

“When that information came out, the people around here went nuts, because one of the pieces of information from the UCR researcher said that the Los Santos region had an above-average R number,” she says. “They saw the information on Repretel News and started to duplicate it in all the chats. ‘Not the Los Santos area! We’re not like that! This is fake news.’”

Helen saw that valuable information that could help residents of her region better understand and respond to the pandemic was being misrepresented and miscategorized as false. She sprang into action, contacting local health representatives and working other contacts she’d amassed during her years in San José. She published articles explaining what the R number really means, and what it meant for Los Santos—and although she got negative pushback from people who thought she was creating a scare, she says she also eventually received thanks and corroboration.

Helen’s work to correct misperceptions about Los Santos’ R number—and Marcela Delgado’s work to share verified information about the COVID-19 vaccine in La Fortuna, at the helm of San Carlos Digital—is a textbook case of what many media observers point to when they describe the importance of local media in Costa Rica’s struggle against misinformation. A local reporter who’s built relationships and trust in the community, sees in real time what misinformation is being shared, and knows how to access official sources quickly, can combat fake news in ways that a national media organization simply can’t.

But Helen, Marcela, and dozens of other local media organizations in Costa Rica can only do this work if their small businesses survive.

It’s a long shot for a media startup to find a business model that works. Anyone who consumes the news knows why: the proliferation of content online means that media have a harder time convincing readers to pay for content, and a clickbait-driven world often punishes responsible journalists who lag behind as they doublecheck their facts. The question isn’t why. It’s: how does a society fix it?

Whose job is it to fuel quality local media?

Supreme Elections Tribunal (TSE) advisor Gustavo Román says that the world’s democratic governments need to step it up.

“I think that democracies around the world need to realize that they can’t exist without the press,” he says. “We need newsrooms. We need journalism, not public relations. If we realize that that is vital, then we have to find a way that it can become profitable again—and if that means public subsidies, I think a reasonable society should explore that… The crisis of the [media] business model isn’t a crisis of media owners, nor of journalists as professionals. It’s a crisis of democracy.”

Marcela Delgado takes a different view. Like other digital media organizations that have sprung up in Costa Rica in recent years, she’s actually pursuing a pretty traditional, advertising-based business model: she’s identified, and then dominated, a niche market by becoming the authoritative digital voice for her region. She says that now, in her fifth year, she doesn’t even have to sell ads. Businesses come to her.

She says the reason it was so hard for her to reach that point, and the reason it’s so hard for more media to follow in her footsteps, is a lack of preparation.

“It’s not about the government subsidizing,” she says. “In [journalism school] we weren’t taught entrepreneurial skills, nor even digital media, although I imagine that now they do. It would be extremely valuable to have some kind of program that helps the student leave university and open his or her own space, rather than showing up at a channel and knocking at the door and being told ‘no’ three months later… That’s what we need to avoid learning everything as we go.”

University of Costa Rica journalism professor Any Pérez explains that, in line with Marcela’s guess, things are changing. She says that while media management has always been part of the UCR Communication School’s curriculum, journalist Yanancy Noguera took over the course in 2018 with a focus on entrepreneurial skills for journalists.

“Our director, José Luis Arce, comes from the private sector… and with his guidance, a pilot plan is being created with Auge,” she says, referring to a Costa Rican incubator that, through the partnership, will now be helping journalism students develop business plans and skills.

Helen agrees that support of this kind would make a big difference.

“It’s really been a huge challenge,” she says. “I’ve tried to train myself along the way—I’m taking a training with the Banco Nacional on marketing.”

It’s tough going without a salary.

“I can’t pay anyone full time, not even myself,” she adds.

Ernesto Núñez is at the opposite end of the spectrum in terms of his business model: his initiative Los Guachis (based on the popular word for informal guards who keep on eye on property for a few coins, particularly parked cars in the street: the guachimán) creates hyper-local reporting to keep municipalities accountable. This initiative that the media organization, La Doble Tracción, was able to start thanks to grant support, now asks residents of the municipalities (Santo Domingo, Pérez Zeledón, and Montes de Oca) to pay in at three monthly subscription levels. These subscriptions, starting at 1,000 colones—under $2 per month—give them increasing say over what the media organization will focus on.

It’s an intriguing model. However, the reaction “hasn’t been as positive as I’d hoped,” Ernesto says. “We’ve sold more than a thousand monthly memberships… but people are often afraid to link themselves to a media organization. Since it’s at a municipal level, you know: small town, big hell.”

He doesn’t mince words in describing why he thinks it’s so hard for local media organizations to make a go of it in Costa Rica, and what happens when they can’t.

“Traditional media… have crapped all over the struggle. They’ve muddied up the path that a media organization has to climb to achieve profitability,” he says, arguing that the reason is that potential subscribers and advertisers have a hard time trusting the media in general. “They’ve really eroded confidence.”

For Ernesto, the lack of support for local media leads directly to misinformation: when independent funding models don’t work, media will do whatever it takes to survive.

“And one of the things [some local media] have done to survive, is to stop doing journalism,” he says. Enter fake news or unlabeled sponsored content.

Promoting the survival of local media

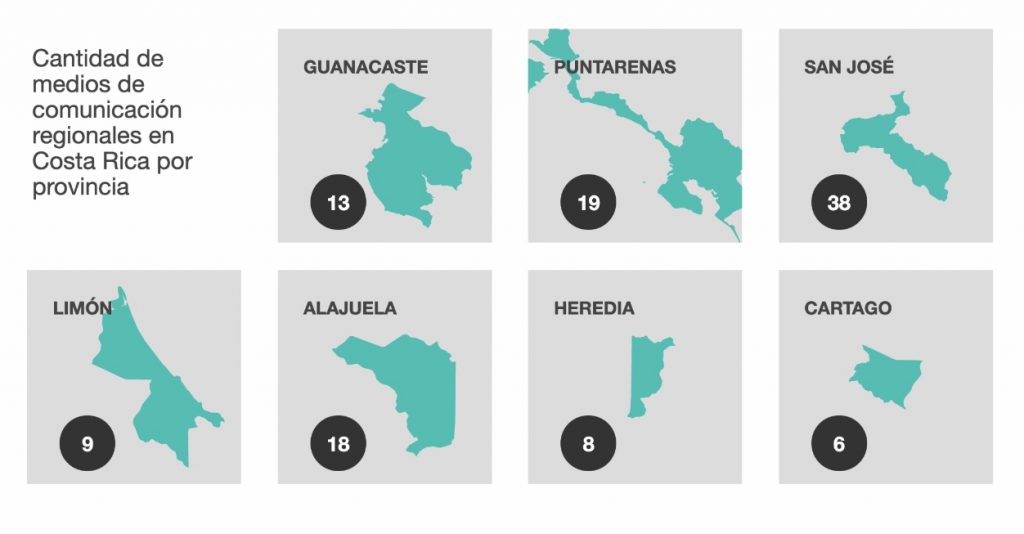

The nonprofit Punto y Aparte, with support from the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, is trying to make its mark on local media’s struggles through free trainings, and through something even simpler: determining what local media exist in Costa Rica’s fragmented media ecosystem. It created a directory.

Kattia Bermúdez, a La Nación journalist who worked on the project, explains that its primary goal was to identify local media so that Punto y Aparte could more effectively offer them free trainings and other resources.

“The idea was to map them, see where they are, what they’re like,” she says. “Also to do a kind of assessment and organize lectures like those we’ve held in recent months to help [local media].”

The directory now includes 140 regional and local media organizations. She says this number has swelled thanks to an increasing number of digital natives; national media with shrinking budgets that lay off their local correspondents, who go off and start their own media companies instead; and even a groundswell of new media during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The largely manual work that went into creating the directory—those in charge carried out extensive searches on Facebook and other social media to identify, little by little, media organizations and determine whether they were linked to political groups or public institutions—has now paid off in that Punto y Aparte can invite all organizations in the directory to participate in their free video lectures, from entrepreneurial skills to, of course, fake news and misinformation.

“Punto y Aparte is the only entity that has really stood with us,” says Helen, of Los Santos Digital, about these efforts. “I don’t think I’ve missed a single training.”

A little help from their friends

Without a clear solution in sight, what seems to be most useful to local journalists in what is, after all, a small country, is mutual support. Kattia Bermudes says the media directory has helpd Punto y Aparte gather information about nascent alliances among local media; Helen says that she’s working with some local media in other parts of her larger region to approach advertisers together. This strategy hasn’t yet paid off, but she thinks it makes sense. Together, small media organizations can offer a bigger bang for an advertiser’s buck, and they’re not competing for the same readers.

She also says that asking fellow local journalists for business tips and encouragement has been key.

“It has surprised me how many regional media there are. Many have been born with the pandemic,” like Los Santos Digital, Helen says. “Instead of rivalry or competition, there’s solidarity… We’re all facing the same problems every day… When I started, I asked for advice from Marcela at San Carlos Digital and Pamela [Valverde] at Alajuela Digital. I talk to Pamela almost daily; we went to school together.”

Despite it all, she says her work is deeply rewarding.

“Regional coverage is totally different from national coverage. You have to seek out the topics—the topics don’t come to you in invitations and press conferences. You have to have a sharper eye to see where the news are… What I’ve loved the most about doing this work on a regional level, here where I live, where I grew up, where I was born, is helping people with timely, accurate, transparent and balanced information. Because they speculate a lot. They don’t now how to inform themselves, so they share fake news or gossip that’s going around.”

Slowly but surely, she’s seen growing trust.

“I’ve been able to serve as a link between institutions,” she says. “And they’ve used the media organization to make complaints, to make themselves heard, and to get solutions to their problems.”

During this month of September, we’re turning our attention at El Colectivo 506 to the health of our democracy, and how disinformation and fake news is causing new symptoms in our society. Join us for “Infodemic,” a month behind the scenes of Costa Rican news. View the complete edition here. We are pleased to be partnering with artist and graphic designer Allan Fonseca, who is creating the illustrations for “Infodemic,” including this week’s illustration of Los Santos Digital’s Helen Naranjo. Learn more about Allan here.