You know a teacher training session is good when the air conditioning breaks.

Yohns Solís, the Latin America Education Director for TeachUNITED, remembers hosting a 2018 training in Sarapiquí that was supposed to be for a small group of educators.

“Forty teachers showed up, and they were almost literally on top of each other,” he recalls with a smile. “So many came that we didn’t have anywhere to put them. They used up so much air conditioning that it started to break down. But everyone wanted to participate: we had an eight-hour training, and eight hours weren’t enough.”

Why are educators in this rural region of Costa Rica so passionate about a training program, at a time when professional development workshops abound? And how is it that employees of the Ministry of Public Education (MEP) came to balance daily classroom teaching with leading a multinational training movement?

Maybe because it’s not a workshop, or even a class. Its creators say the real magic lies in the ongoing learning communities it creates so that teachers can not only get support over a long period of time, but also support each other. And the trainers are not international experts or former teachers who’ve long since lost touch with the demands of daily classroom life. Rather, they are current public school classroom teachers like Yohns who have been trained to pass on the TeachUNITED program to their peers.

“We understand very clearly how not successful a workshop can be,” says Sarapiquí resident Meghan Casey, one of the founders of TeachUNITED. She explains how this local training effort, informed and supported by an international initiative, focuses not on one-off sessions, but on creating “practice networks and groups for professional learning.”

So how does it work—and how did it start?

A global network with Sarapiquí roots

Like many rural entrepreneurs in Costa Rica, Meghan Casey wears many hats—and like many international residents in rural communities, she has become deeply involved in more than one local issue. The Irish-Canadian-Costa Rican mother of three runs Chilamate Rainforest Eco-Retreat with her husband, who is from Sarapiquí. She also works as the Senior Director for Latin America for TeachUNITED (TU), which she has helped to lead from the start.

The initiative trains teachers across the United States with a focus on small, rural communities, as well as in Africa and Latin America.

While the international effort now crosses borders and oceans, Meghan’s involvement stemmed from her love of her community and her perspective on education as a parent. Her work to bring the TeachUNITED training model to local teachers was at first informal but is now a formal partnership with the Ministry of Public Education (MEP). She runs a team of five TU staffers for the Latin America region—all five of them in Sarapiquí. Two of them spoke to El Colectivo 506: Yohns, who described that jam-packed 2018 session, and Armando Bello, the program’s operations director, work full-time for TeachUNITED during the day, and then teach at the local MEP Integrated Adult Education Center (CINDEA) at night.

In other words, MEP employees in this rural region are now helping to lead a training program that affects schools and students throughout Latin America.

The program uses a two-phase, train-the-trainer mode. In the first phase, staff from local partners—nonprofits that work with schools, or government partners such as the MEP—are trained on the TeachUNITED model, from the research behind it to the tools needed to coach teachers. In the second phase, these trainers pass on what they’ve learned to teachers, with ongoing support from TU.

While the primary curriculum outlined on the program website covers topics including mindset, blended and personalized learning, student engagement, and effective use of student data, through four 12-hour units, Meghan explains that TU sticks with a given school for at least one year, sometimes two or three. Teachers form cross-disciplinary groups then support each other for ongoing discussion, classroom observation, and support from their TeachUNITED peer trainers like Yohns and Armando as trainees work to implement what they’ve learned.

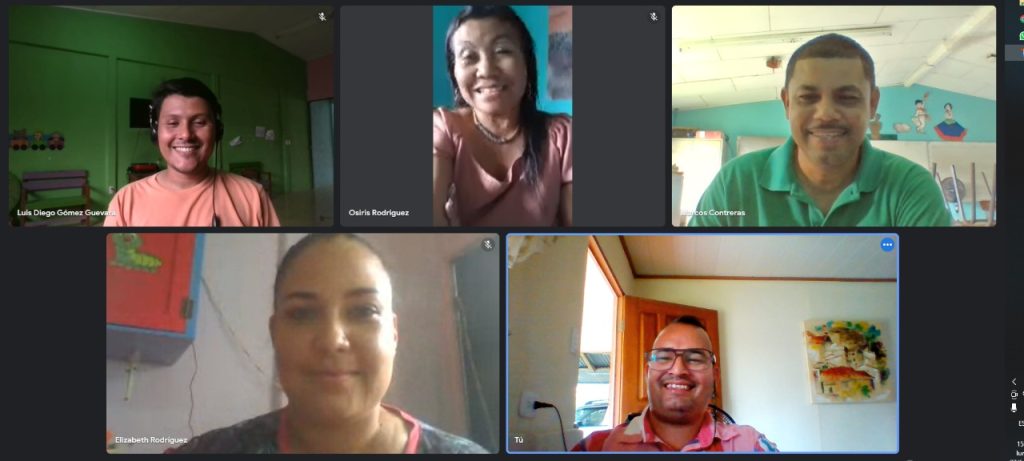

“The learning communities are the best part,” says Yohns, describing the diversity of approaches teachers can compare “when you combine [teachers from different disciplines] within the same institution, or in an exchange among institutions… English teachers can share with Spanish teachers how they have been implementing the growth mentality. This is done through webinars that lately, have had to be virtual, but we hope to resume” physical meetings.

Jesus Alfredo, a regional training specialist with the MEP, says one of the advantages of the program is simply the support that TeachUNITED’s teacher-trainers provide the Ministry in visiting and maintaining a connection with schools that the MEP can’t adequately cover.

“There are 138 institutions in the region, but not all of them can be covered by the central MEP [offices]. It’s really hard to assign resources to them when we know that at a national level, there are so many institutions in these same realities: lacking access to technology, lacking access to trainings;” he says. “We’re in constant communication with the TeachUNITED staff in the area: they tell me what phase they’re in, which schools they’re visiting. It’s so important to have this connection to the schools.”

English, technology, and teachers’ pride

The program works with teachers of all disciplines, but since the current edition of El Colectivo 506 is focused on the teaching of English as a Foreign Language, we spoke with English teachers about how the training has affected them.

Armando Bello, a MEP English teacher and TU’s operations manager for Latin America, says he loves the way that the training explores deeper, more philosophical questions such as the purpose of an educator in students’ lives. These are topics that teachers lose track of in the day-to-day grind.

“It’s stuff they don’t teach at university, and it’s so necessary,” he says of the modules on mindset, or the power of the teacher in students’ lives. “We can make such a huge impact… but sometimes we can forget our purpose as an educator. We might show up to fill a space.”

José Adolfo Chaverri Chacón, a 20-year veteran primary school English teacher at La Guaria in Puerto Viejo de Sarapiquí, says that for him, the most important result of the TeachUNITED training was bringing him up to date. He says that the training exposed him to the power of various applications to engage students in language learning, revolutionizing the way his classroom works.

“When I started teaching 20 years ago, I didn’t even have a computer. If I compare that to today, the difference is vast,” he says. “The course helped me see a different way to plan my activities.”

He saw an immediate impact on student engagement.

“The knowledge I received and can pass on to my students—I feel like it worked. It really worked,” he says. “I look at the students and can see their motivation, because they say, ‘What app is the teacher going to use in the next class?… They see a huge difference from the way I used to teach. They’ll say to me, ‘Teacher, I got home and looked up the app we used in class, and I love it. I even want to use it in my computer class.’”

For Natalia Espinoza Solano—who has been teaching English for five years and works with first through third graders at the Centro de Educación Prioritario Buenos Aires in Horquetas, Sarapiquí—technology has been a big part of her TeachUNITED experience as well. However, her biggest takeaway is more philosophical.

“I think the most important part of this program is understanding that the center of education is the student,” she says. “We’re just a guide for them, but they have to acquire their own knowledge.

“We’re used to the idea that the teacher does everything,” she says. “Not anymore.”

For Yohns, as a TeachUNITED staffer but also as a MEP teacher, one of the most important elements of the program is the way it seeks to change teachers’ view of evaluations. Last week in El Colectivo 506, we reported on the increased rigor and scope of English evaluations in Costa Rica—but that data will only help teachers improve their instruction if they are given support in how to do just that.

“We want to give teachers the opportunity to see… that evaluation is a tool,” he says.

Part of that process? How TeachUNITED evaluates itself.

Multi-level assessment

As any educator knows, some professional development opportunities might come without any assessment; others assess impact based on pre- and post-surveys focused only on the participating teacher. TeachUNITED uses multiple assessments, working with each local training partner to develop a tailor-made plan that incorporates teacher and administrator feedback, classroom observations, and student achievement.

The program in Sarapiquí applies third-party pre- and post-student assessments including EasyCBM Math, Early Grade Reading Assessment, and Learning A-Z Spanish Literacy, according to the TeachUnited 2021 Impact Report. A 2019 evaluation showed that Sarapiquí students showed a 25% increase in student performance after their teachers’ TU training experience. Across Latin America, the students of TU-trained teachers have showed a 12% increase in school pass rates.

Another important retention data point: teachers staying in their profession, despite the outsized demands of the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, evaluations showed an increase of 6% in trained teachers’ intention to stay in the classroom, according to the Impact Report.

Natalia says that for her, the community that TeachUNITED creates among teachers from a variety of disciplines and contexts has helped her rediscover her passion for her profession.

“In Costa Rica, [teachers] have a lot of administrative tasks, and that limits our work in education itself,” she says. “We have to work on a lot of different committees that the MEP assigns us to… We should simplify and focus on teaching itself.”

Financial limitations

Asked about the program’s limitations and areas for improvement, Natalia says that the move to virtual sessions at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic meant that she and her fellow trainees missed out on in-person interaction. She hopes that the ongoing support they’ll now receive will include physical gatherings: “I’d like to see different conversations with teachers who were in the [virtual] program, but can now get together.”

Aside from that, the primary limitation mentioned by each MEP employee consulted by El Colectivo 506 is the program’s reach. They want to see more schools and students included. However, the effort would require further financing—ideally, institutional financial support within Costa Rica—to expand much beyond its current scope, Meghan says.

Aside from some grant funding for Latin American programming, a partnership with Amazon to work with the schools in Ostional and a contract with a private school in Monteverde to work with its teachers, “we’ve survived through donations,” she explains.

Jesus Alfredo says that from his perspective as a MEP training specialist, “one of the things I’d like to see from TU is having more institutions in the program. For us at the regional level, and also for the [national] MEP, it’s really hard to see all the schools. If TeachUNITED could help us with that, maybe it’s a little greedy to ask that they increase the number of visits to schools, but it’s just a fact that we’d love that.”

He adds that he sees potential for the program in even more isolated territories.

“We’d like to have more [TeachUNITED] in the frontier region,” he says. “I’ve also worked in indigenous regions, and I’d like the program to consider that as well, maybe doing a program with indigenous populations that are in very vulnerable, low-resource areas.”

Globally, TeachUNITED—which has trained 24,854 teachers serving 637,282 children, according to its 2021 impact report—seeks to expand its reach to train teachers who serve more than 3 million worldwide.

English teacher José Adolfo says he hopes some of those additional teachers are in Costa Rica, particularly so that more schools can take advantage of the opportunities that technology presents.

“I wish this could be for 100% of Costa Rica’s teachers,” he says. “A lot of us struggle with technology, but if all the TeachUNITED trainers are like the ones we had last year, I think no one would struggle with it anymore…. It would be an incredible tool to help us with day-to-day life in our classrooms.”

Natalia says she hopes that these communities of practice that put the focus back on the craft of teaching can be part of a bigger change in the way the art of teaching is revalued and respected.

“My recommendation to the Education Ministry would be to expand this program for more teachers, and to place more emphasis on the work of teachers,” she says. “We’re leaving for last what we’re really passionate about, and what we’re really responsible for.”

How Costa Rica transformed the way it assesses its English students