In 2018, the Costa Rican government set a goal: to graduate completely bilingual high school students.

When? No later than 2040.

How? Achieving this goal is a complex task that requires the application of many solutions at once, all increasing students’ exposure to a second language so that they can function in a wide range of situations. However, in the words of Manuel Rojas, academic advisor and coordinator of the Alliance for Bilingualism at the Ministry of Public Education (MEP): “What we don’t evaluate, we can’t improve or control.”

In other words: if Costa Rica wanted its students to speak English, the country first had to start evaluating their language skills. This was a big challenge in a country where national exams were limited to written questions, and lacked alignment to any meaningful language standard.

“Before, we had a paper-and-pencil high school test [examen de bachillerato], which really didn’t allow us to know what the person can do with the language,” says Manuel. “In order to do that, you need a framework to determine students’ progress on the skills in the curriculum.”

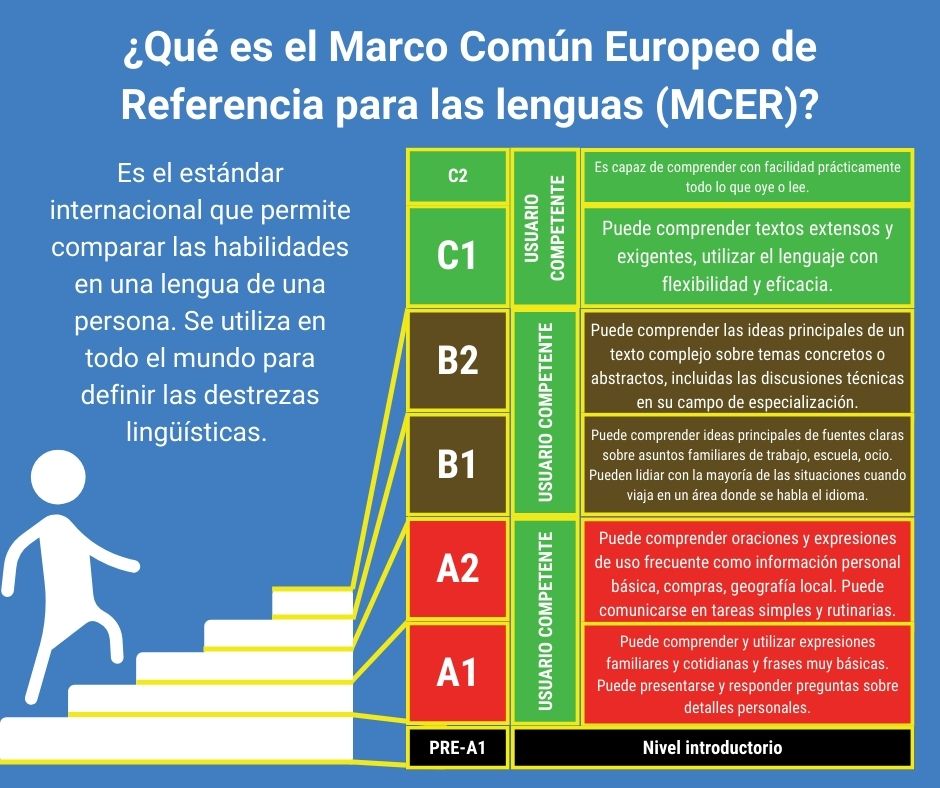

That framework that the MEP has adopted is the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR), which—through a classification in three bands, A, B and C, subdivided into two levels each—can locate a person’s mastery of a second language. The framework measures their oral and written comprehension (listening and reading) and their oral and written production (speaking and writing).

According to Manuel, the MEP has different exit profiles for high school students: “For some schools it is B1 and for others it is B2 or higher. It depends on the amount of exposure students have to the language” in each school’s program of study.

The exit profile for primary school students is A2.

To evaluate this framework in Costa Rican students in both public and private institutions, the MEP partners with the School of Modern Languages (ELM) of the University of Costa Rica (UCR).

“Until 2018, [the UCR] had been doing standardized, paper-and-pencil test. In 2018, the Education Ministry contacted us to see if we could help develop digital tests,” recounts Allen Quesada, director of the ELM and a researcher with the school’s Evaluation and Certification Program. “2019 was the great experience of transforming standardized tests to a computer format. A positive effect of this innovation was that they are tailor-made exams aligned to the international standards of the Common European Framework, and we incorporated elements of the English curriculum. It’s no longer about passing or failing the test: rather, it measures what the student can do with the language.”

The process of creating this test was complex. Both institutions had to map the connectivity of the schools to be evaluated, and then create formats that would adapt to all possible conditions. That’s how they developed three testing formats: an online format, an offline format, and a hybrid format. The latter two formats require the exam to be downloaded beforehand to a computer.

In 2021, only 1% of the population evaluated took the exam online; 14% took the exam offline; and 85% took the hybrid format, through which answers can be submitted electronically as soon as the student finishes the downloaded exam.

Test coordinators needed to prove that the tests being used were the right fit for the MEP’s English program and could generate data that the MEP can use to adjust its plans and strategies for bilingualism.

“In the academy, we’ve conducted research on the instruments [to show] that they really measure what we say they are measuring,” Allen replies when asked whether these tests are reliable. He refers to the ELM’s more than 30 years of experience carrying out placement tests and language proficiency certification.

“We’ve bought international [standardized testing] licenses and tested students on them and then on our tests, and we’ve found that there’s a very high correlation” between the two scores, says Allen. “In terms of validity, reliability and how practical the test is, we have scientific data that supports the effectiveness of the instrument.”

Developing these tests involved considering the work that teachers must do in the classroom to implement MEP curricula.

“That is very important, to have a reliable instrument that reflects what is done in the classroom and international standards.,” says Allen.

So far, the UCR’s Standardized Language Proficiency Test (PDL) has been applied only in 2019 and 2021. On both occasions, it was given to the entire 11th-grade student population—the final year of academic high school in Costa Rica. In 2021, a Test of English for Young Learners (TEYL) was also applied to a sample of fifth graders—the first group of Costa Rican students that have used the new English curriculum since they started school.

A disappointing baseline that sparked change

From the outside, it might seem that changing a country’s tests is not that complicated: a simple matter of signing an agreement or publishing a new policy. But improving the way Costa Rica measures its teachers’ and students’ ability to speak and understand the English language has required the perseverance of many—through changes in presidents, ministers of education, and their respective language teaching initiatives.

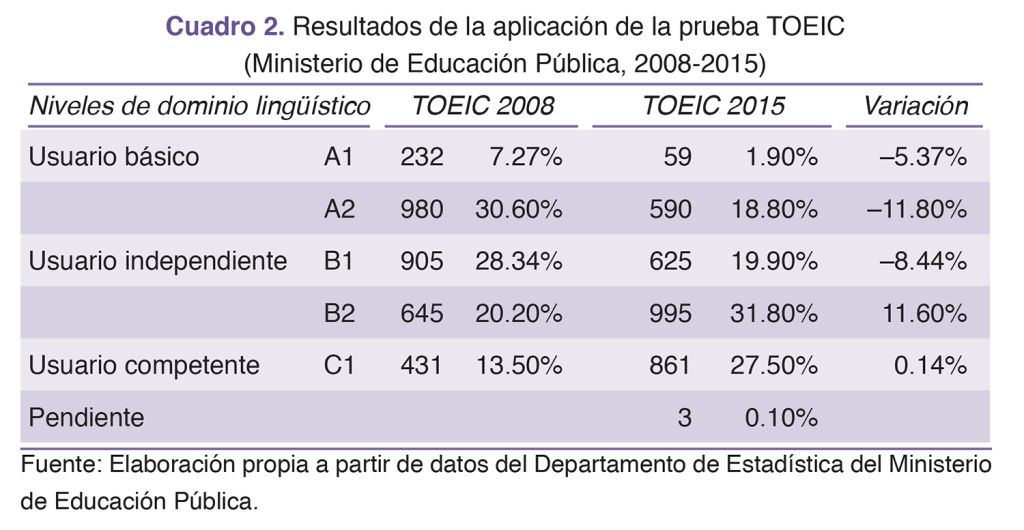

The year 2008 marks the baseline for understanding what is happening with the teaching of a second language, particularly English, in Costa Rican education. That year, the MEP applied the Test of English for International Communication (TOEIC) exam to most of its English teachers. The results showed that only a third of these teachers had reached the B2 or C1 level, the required proficiency for language teachers.

That same year, the presidential initiative Costa Rica Multilingüe carried out an English proficiency test with 705 high school students (today, this would represent 1% of this population) which showed that 66% were still at the A1 level—basic user.

“The data revealed by this test was very discouraging,” says Manuel about what happened in 2008.

The MEP’s first reaction, Manuel explains, was to redefine the hiring requirements for English teachers, and to generate professional development programs for existing teachers in alliance with the National Council of Rectors (CONARE). The trainings sought to help teachers improve their command of the language.

In 2015, the MEP re-evaluated its English teachers.

“The improvement was palpable. The pyramid was inverted: in that test, 60% [of teachers] were at the expected levels for educators,” says Manuel, referring to bands B2 and C1.

In addition to changes in teacher hiring and training, the MEP implemented new curricula in 2016 to improve the way English is taught. Manuel explains that the new curricula were applied in a rolling manner: that is, in 2017, 1st graders and 7th graders started using the new programs and continued up the following year.

“The first generation hasn’t yet graduated,” says Manuel, referring to the students who entered first grade in 2017 and won’t graduate from high school until 2025. That’s when the impact of the new curriculum can be measured fo the first time.

A regional pioneer

“The UCR test is an external evaluation of what we are doing in the Education Ministry,” says Manuel. Allen agrees, and says this is the best way to monitor the achievement of goals of the new programs.

“This change is a milestone not only regionally but also internationally. We are one of the first countries that evaluates with a language proficiency test,” says Manuel. “We do it because we really need to know what skills students are achieving.”

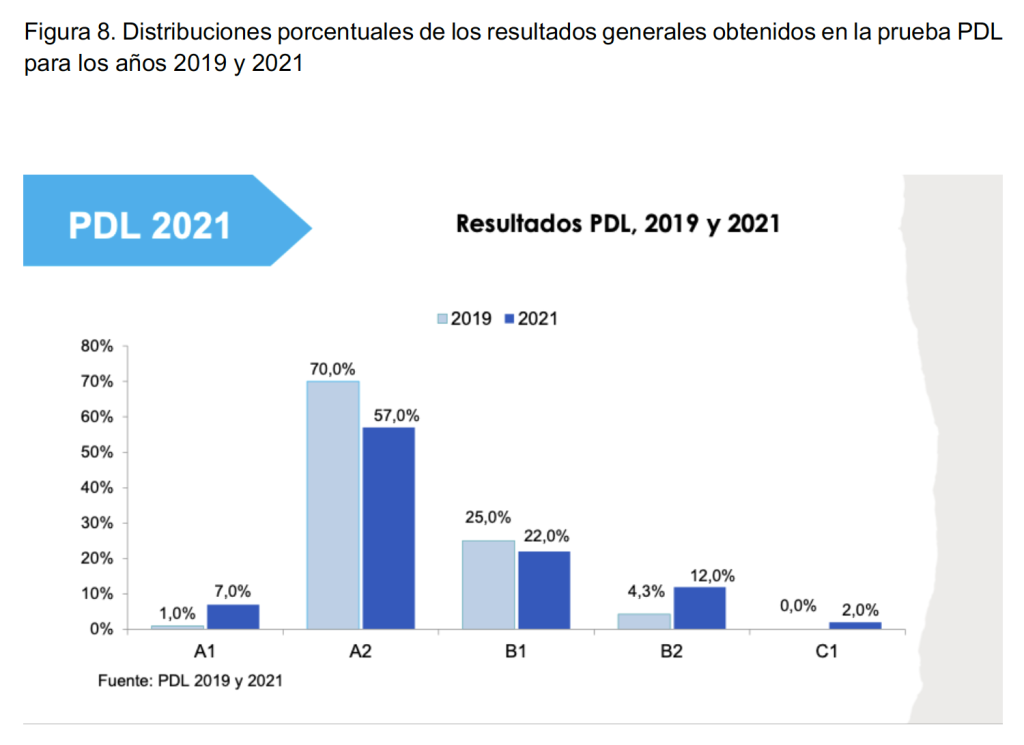

Although the system has not yet reached its desired results, the PDLs applied to the entire 11th-grade population of Costa Rica show improvements in the English proficiency of secondary school students.

“If we take a serious and responsible look at it, I think we have to say that despite the pandemic, there was progress,” says Allen.

In 2019, 70% of students were in the A2 band, and only 1% in the A1 band. That data is very different from 2008, when 66% of the evaluated sample was in A1.

By 2021, students in band A2 decreased to 57%. Band B2 went from 4.3% to 12%. In addition, 2% of the student population reached C1.

Just as there were improvements between 2019 and 2021, there was also a setback: the 1% in the A1 band in 2019 grew to 7% in 2021.

According to the 2021 PDL report, that 7% “is mainly made up of 4,830 night school students and CINDEAS [adult education centers].”

The PDL’s provincial results show that the number of students in A2 was up to 12 percentage points higher in Costa Rica’s coastal provinces, compared to the provinces that make up the greater San José area.

“Our traditional academic high schools and our night schools offer less exposure to Englsh: three lessons in [7th to 9th grade] and five in [10th and 11th]. That’s where more students are staying in the A2 band,” says teacher Juan Carlos Aguilar Fernández, comparing them with other modalities such as Bilingual Experimental Schools; bilingual tracks within academic schools; technical schools; and private schools.

How can the MEP change this reality, especially for night school students who have limited classroom time because of their jobs?

“Review the curriculum and innovate by using combined models, where students can continue for additional hours with digital platforms that allow them to be exposed outside of classroom time—for example, when they are at work and have their break,” says Manuel.

Juan Carlos has been working as an English teacher for 28 years in the academic night section of the Liceo de Paraíso, Cartago.

“The reality of our institution is very different from the rest of the schools,” says Juan Carlos. “For many [of our students], it’s been 5, 10, 15, even 20 years since they left [traditional] school.”

Juan Carlos says that his students’ jobs prevent them from not only having longer school hours or studying extensively at home.

He says that during the 2021 test, his students were nervous, but also motivated. The results, he says, were not surprising. They also weren’t what he wanted.

“The vast majority of the night students were located in band A2. Some were in B1 and a few others in A1,” he says.

Both the improvements and setbacks seen between the 2019 and 2021 PDL results occurred in the midst of a pandemic, where students received exposure to largely virtual teacher training. According to Allen and the UCR researchers this caused both improvement and setbacks.

“[In a pandemic] when you are learning a language, it is more difficult to obtain resources. Students who are just beginning [to learn the language] are more affected than those who already know a little English,” says Allen, who shares two hypotheses about the improvements shown.

“ONe hypothesis that is gaining strength is that students, despite being in a pandemic and doing remote learning, had exposure to devices and programs and games, causing a positive impact,” he says. “The other hypothesis is that English teachers had technological resources… and were able to provide audiovisual material, audio, videos that weren’t so common before. That has helped.”

The 2021 testing done with 3,011 fifth grade students from different parts of the country showed that this population remains mostly A1 (66%) and A1+ (25%) band. Only 8.6% had reached the desired level for the end of primary school, A2. La expectativa es que a finales del año 2022 que finalizan la primaria la gran mayoría se encuentre en la banda A2.

The future of PDL in Costa Rican education

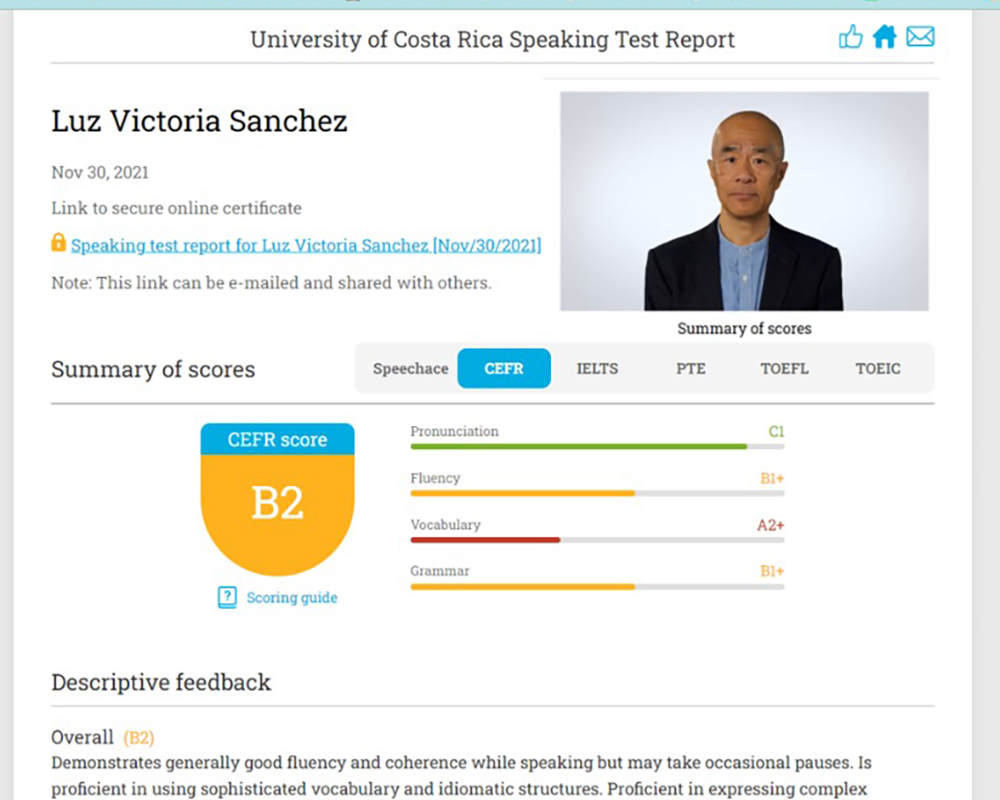

The implementation of these Language Proficiency Tests is here to stay. The next step is to be able to assess beyond comprehension—that is, to assess students’ speaking and writing. Allen and Manuel explain that for this they are about to implement a standardized test that uses artificial intelligence (AI) developed by the UCR.

“This year we want to evaluate oral [production] by sectors. It’s a challenge with the budget,” Manuel says about how they are going to implement this new evaluation and why it will not be applied to the entire population. “We have already evaluated students from bilingual sections with artificial intelligence and compared it to an expert face-to-face UCR evaluator. There was a high degree of correlation, which means that the artificial intelligence result is highly relevant. We want to implement this test as soon as possible”.

“The idea is to provide comprehensive feedback to students,” Allen says of the oral production proficiency tests developed at UCR. “While many automated speaking tests provide information on pronunciation and fluency, we chose to provide information on the full range of language skills—pronunciation, fluency, vocabulary, grammar and coherence, just like a qualified human evaluator. In less than 10 minutes, a person can be evaluated with results in real time”.

The next step is to strengthen the PDL in the other languages offered by the MEP and private schools, especially French, Italian and German.

However, the main obstacle to expanding these tests, beyond the budget issue, is school connectivity.

“If we had connectivity, it would allow us to have the results more quickly and use AI for the other two skills,” says Manuel, “Connectivity becomes a fundamental element to be able to carry out this and other applications.” (Read more about the challenge of connectivity in Costa Rican schools in El Colectivo 506.)

At the primary level, the TEYL language proficiency test will continue to be applied to a fraction of the student population in order to obtain statistical data.

“We want to do mapping so we can make decisions,” says Manuel. “Due to budget restraints, we cannot evaluate all primary schools.”

Projections for graduating bilingual students

Testing for 2022 is already underway. By the end of the year, all 11th-year students will take the test before graduation. Expectations are high.

“This year, 2022, is the first class of sixth graders that will allow us to measure the scope of the new curriculum,” says Allen.

“Let’s say that in 2022, 41% of the students are in the desired bands,” says Manuel, extrapolating the progress shown between 2019 and 2020 into the future. “If we continue like this, we would reach our goal before 2040.”

What is clear to both Allen and Manuel is that the application of these Language Proficiency Tests is an essential element in achieving the national goal.

“This evaluation allows us to see where to look and where to make improvements,” says Manuel. “We have mapped by school, allowing us to make personalized changes for each institution. That’s the value of this type of evaluation.”

“It’s very important. Without data you can’t just blindly improve,” says Allen. “We need reliable data about what is happening in the country, in regions, to make changes and improvements, and to be able to support the weaknesses of those schools and institutions.”