The archaeological heritage of the Huetar Norte Region is not a vestige of the past: it is an opportunity to rethink development from the perspective of identity, education, and co-responsibility.

Gerardo Quesada Alvarado reports the story in this article created with a grant from “Journalism in Times of Polarization,” a project of the Latin American Solutions Journalism Fund. The Fund is an initiative of El Colectivo 506 in alliance with the SOMOS Foundation. “Journalism in Times of Polarization” is made possible by the support of the Canada Fund for Local Initiatives. The Canada Fund for Local Initiatives—administered by the Embassy of Canada—funds small-scale, high-impact projects aimed at empowering vulnerable communities and populations and promoting human rights for all people. The article was published by El Norte Hoy on Dec. 22, 2025. It was adapted and translated here by El Colectivo 506 for co-publication. We used Google Translate to support the translation. Some images used in this report were created using artificial intelligence.

Costa Rica’s Northern Zone is not just volcanoes, rivers, wetlands, and cattle ranching: beneath the farms and rural roads lie ancient Indigenous settlements whose history remains invisible, fragmented, and at risk. This is not due to a lack of value, but rather to the absence of clear public policies, a lack of community awareness, and tensions between conservation, private property, and productive development.

In communities such as Venecia de San Carlos, Cutris Archaeological Site, Cerros de La Fortuna, and Alma Ata in Sarapiquí, archaeological sites show evidence of the existence of complex societies long before the formation of communities as we know them today.

Kendra Vanessa Gamboa, anthropologist and national researcher, identifies Cutris as part of the territory of the Botos Indians (900 and 1550 AD) articulated through a network of roads that connected with Montealegre to the northwest, Veracruz to the northeast, Crucero to the southeast and Concepción to the southwest.

Juan Vicente Guerrero, an anthropologist and researcher at the National Museum, points out that Cutris is a key to clearing up a series of unknowns about the life and history of the pre-Hispanic groups of the Northern Zone—something that can only be achieved by preserving and investigating this and other sites in the surrounding area.

This infrastructure demonstrates advanced civil engineering knowledge. Some of these roads were even oriented towards geological features such as the extinct volcanoes of Platanar, Porvenir, and Viejo, which served as regional landmarks. But what has become of them?

Abandoned sites

Professor Jesús Montero, from San Carlos, warns of the complete neglect of the Cutris archaeological site, noting the scant knowledge about it even among the district’s residents. Montero points out that the Las Huacas School was built directly on the archaeological site, while another part of it remains in private hands and is bisected by the road connecting Venecia and Pital de San Carlos.

This situation is not unique. In the Northern Zone, many archaeological sites are located on active agricultural properties, far from state oversight. The expansion of monocultures, the opening of roads, and looting—all of these operate in a context where the local population is often unaware of the value of the heritage they inhabit.

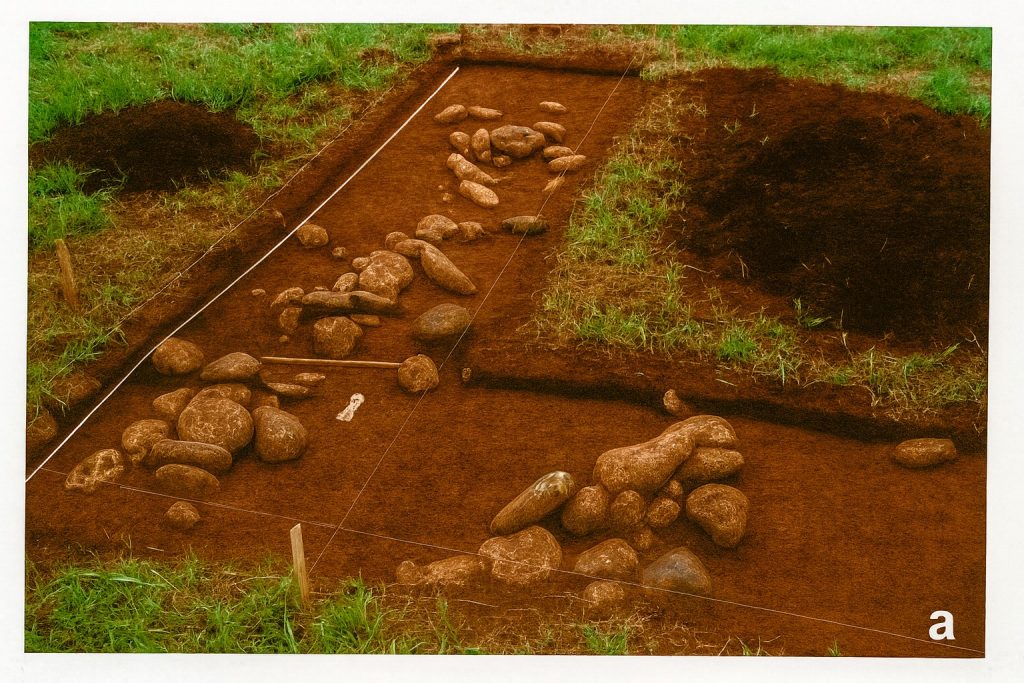

Something similar occurs at Cerro Fortuna, in Fortuna de San Carlos—or “Vista al Cerro,” as the archaeologists named it. There, among the forest and the mist that descends from the slopes of Arenal, they’ve found burial sites, paved floors, and ceremonial vessels belonging to the Arenal phase between 500 BC and 500 AD.

It is a funerary space, a place of farewells and rituals where the ancient inhabitants honored their dead with a delicacy that we can barely imagine today.

An example of what works

In contrast, Alma Ata, in Sarapiquí, demonstrates that other paths are possible. Discovered in 1999 within an orange grove, this ancient pre-Columbian cemetery has become an archaeological park integrated into a local tourism project.

In the Northern Zone, many archaeological remains are located on active agricultural farms, far from state oversight.

The advance of monocultures, the opening of roads and looting operate in a context where the local population often does not know the value of the heritage they inhabit, assets that allow them to observe mounds and understand what daily life could have been like in an indigenous village, with its plaza, its communal structures and its ceremonial spaces.

Although further research and protection are still needed, the site demonstrates that it is possible to balance conservation, tourism, and community development.

The challenge of conservation

Although informal tourism practices exist in sites with archaeological remains, the Law of National Heritage, No. 6703, prioritizes the protection of archaeological heritage over any tourist or commercial use. It also assigns the National Museum a technical and custodial role, not that of a tour operator.

The primary challenge lies in the fact that the museum’s mission is not directly geared towards tourism and lacks the precise structure and legal framework to develop archaeological tourism products.

In addition, the law places archaeological heritage within the public domain, inalienable and owned by the State, which limits the possibility of granting concessions to private entities for its development. The investment required for security and maintenance to make these sites publicly accessible represents another significant obstacle.

Residents of these areas play a vital role. When a community embraces its heritage, it protects it.

Constructive solutions

Initiatives are beginning to emerge at the local level. Flor Blanco, a municipal councilor in San Carlos, along with other councilors, promoted a motion to encourage the identification, protection, and dissemination of the canton’s archaeological heritage, as well as the creation of a physical space for its study and exhibition.

Flor says she believes this is one way to revitalize the canton’s economy through rural and community-based rural tourism.

“We must raise awareness about the recovery and preservation of our heritage so that it can serve as a historical foundation,” she says.

Luis Carlos Jiménez, director of the one-room school in Las Huacas, says that students and teachers find archaeological fragments during daily work.

For him, education and community ownership are key to long-term protection.

Edwin Aguilar Morera, president of the Chamber of Tourism Entrepreneurs of Río Cuarto, says he believes that archaeological tourism could diversify the regional economy, provided that it is developed in a regulated and gradual manner.

He explains that several excavations have been carried out in various areas of Río Cuarto; however, there is no designated archaeological site with potential for development. However, he highlights the proximity of this canton to archaeological sites such as Cutris and Alma Ata.

“It is worth mentioning that the local government is in the process of forming a geopark together with other municipalities. The idea is to promote this type of initiative not only at the level of visitation but also for international study,” Edwin explains.

Towards a creative solution

Experts propose alternatives that don’t require formally opening all sites to the public, but rather designing low-impact models. Promoting outreach spaces in existing locations such as parks, green areas, and recreational spaces could become essential for constantly reminding communities of their archaeological wealth.

The experience of Guayabo de Turrialba [editor’s note: this archaeological site in the province of Cartago was declared a National Monument in 1973] demonstrates that when a community embraces its heritage, it protects it. Replicating this model in the Northern Zone would require training, incentives for agricultural landowners, and a consistent institutional presence.

Other options include information kiosks, pop-up and temporary exhibitions, and guided and interpretive on-site tours that fulfill the objectives of visibility, information, education and promotion of the identification and appropriation of archaeological heritage by the communities.

There are also other emerging examples of collaboration. The National Museum is working with EARTH University at the Las Mercedes site and is planning a project with the Costa Rican Tourism Institute (ICT) at Playa Panamá to create heritage interpretation trails. These are positive steps, but still isolated.

The archaeological heritage of the Huetar Norte Region is not a vestige of the past: it is an opportunity to rethink development from the perspective of identity, education, and co-responsibility.

The invisible cities are still there, underground. The question is no longer whether they exist, but whether there will be leadership, coordination, and the will to integrate them into the present without destroying them in the process.