I’m originally from Pérez Zeledón, a rural area in southern Costa Rica. A few years ago, I moved to Limón to study Social Communication at the University of Costa Rica, Caribbean Campus, a move that meant changing my environment and facing a reality different from what I was used to. I arrived with a professional dream, but over time I understood that this path also brought with it questions and lessons that went beyond academics.

While living in Pérez Zeledón, I thought Limón was a dangerous and violent place. That image didn’t come from direct experience, but from stories repeated in the media. However, living and studying in Limón, as well as working as an assistant on social action projects, allowed me to question that narrative. For most of the year, news from the province focuses on fear and violence. Only in August, Costa Rica’s month for Afro-descendant history, is there space to talk about its culture, music, and cuisine. But what happens the rest of the time to the people who live here?

These partial views oversimplify a complex reality and obscure the root causes of the problems facing the province. Talking about violence without addressing structural violence is a way of simplifying reality. According to a story published by Diario Extra on Nov. 3, 2025, the province of Limón faces 45 red alerts in schools tied to infrastructure problems [editor’s note: an orden sanitaria is issued by the Health Ministry; a red alert can lead to the partial or total closure of a school to protect student safety] and a total of 198 health orders in the province, making it the third province with the most such orders nationwide. In this context, opportunities for children, adolescents, and young people are severely limited. When access to a quality education is almost nonexistent, when institutional interest is scarce, and poverty permeates daily life, many people seek ways to survive in an environment that offers few alternatives.

Added to this is a historical structural racism that manifests as discrimination, deep-rooted prejudices, and public policies that have marginalized Limón. Although the majority of Costa Rica’s exports and imports pass through the province, this wealth does not translate into sufficient public investment, adequate infrastructure, or improved living conditions for its inhabitants. Limón, with its large Afro-descendant, Cabécar, and Bribri populations, sustains a fundamental part of the national economy, yet it receives persistent unequal treatment that perpetuates social inequalities and ensures that exclusion continues to shape the lives of many communities.

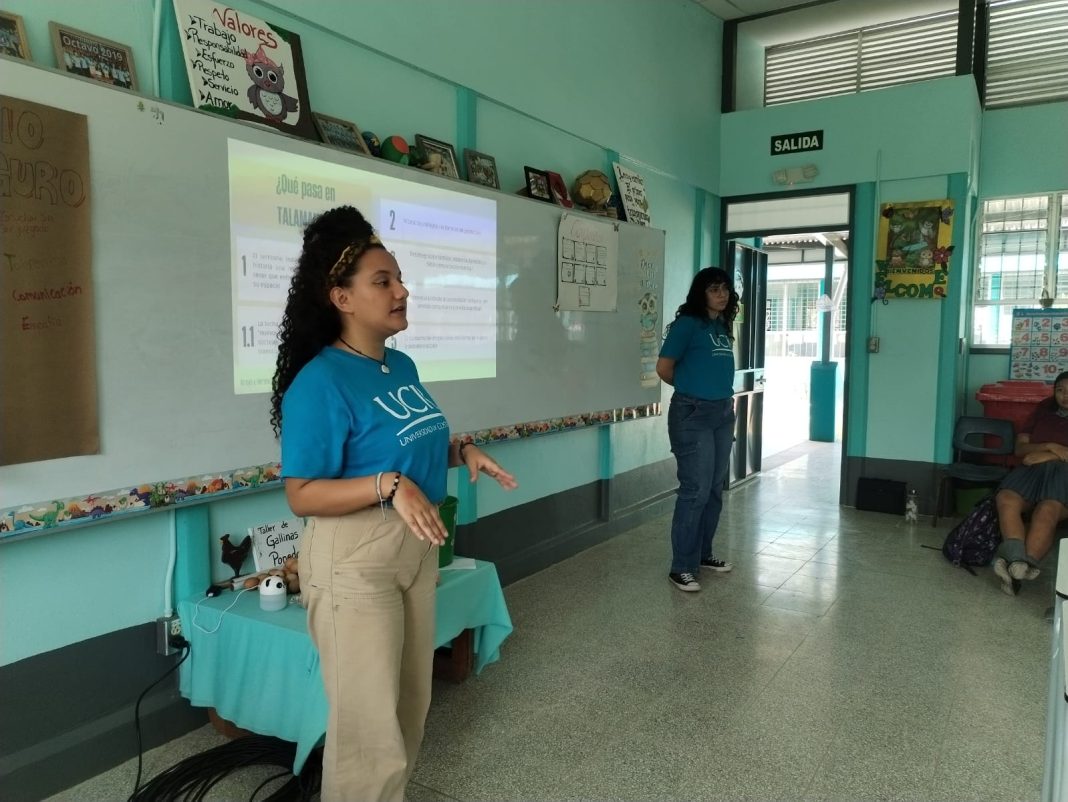

At the university I attend, working closely with communities has been an opportunity to learn how to intervene: not hastily, or by imposing one’s will, but by listening, understanding the context, and recognizing that each community is different. Parallel to this process, outside the university setting, participation in the workshops of El Colectivo 506 opened up a different learning space for me. Through approaches focused on constructive and transformative narratives, these workshops offered tools for rethinking the role of journalism and communication in contexts marked by inequality. More than providing definitive answers, these spaces raised essential questions: how can we tell stories without reinforcing stigmas? How can we spotlight citizen participation and promote it? And how can we adopt a narrative ethic that contributes to social cohesion?

These lessons involve pausing before writing, contextualizing the facts, and asking oneself who benefits from the story being told. It means telling stories from the ground up—not romanticizing reality, but rather acknowledging its complexity, its causes, and also the collective efforts that sustain community life.

Journalism and communication have a responsibility that goes beyond the immediate headline. Being uncomfortable, listening, and delving deeper are essential. Only in this way is it possible to build fairer narratives—ones that speak not about communities, but with them.