“I want to disappear,” my daughter said.

“What?” My hand, resting on her shoulder, tightened its grip instinctively to match the squeeze of my heart.

“It’s not fair, Mom. I want to disappear, too.”

We had just turned around on one of our quarantine walks on a dirt road near the top of Volcán Irazú to find that my husband, about a hundred feet back, had been completely subsumed in a sudden fog. Cartago is known for las brumas that sweep through its hills, and this one had made him disappear completely. My daughter, her pink sweatpants half-tucked into unicorn-patterned rubber boots, had made to run off into the mist herself, but I’d stopped her. He was crossing a rickety bridge over a deep gorge, and a car might pass, and we couldn’t see him, and I was afraid. I was afraid in ways that had nothing to do with anything around us at that moment. I was more afraid than I could ever express.

“I don’t want you to disappear,” I said, just as my husband’s faint form finally became visible. I tried to say something more, but I couldn’t.

The only word on my lips was Allison.

Allison Bonilla. The girl who did disappear on March 5th, 2020, walking through the cool night just a short drive from where we were standing, heading home from class in one of the most beautiful valleys of the most beautiful country. The girl whose mother left their house to meet her daughter halfway as she walked home from the bus stop.

Allison never arrived. She was only 18. She just wanted to go to class, and to come home again.

Their neighbor later confessed to her rape and murder.

Allison became a name on millions of lips. She became a chill in the blood of all her country’s mothers, all mothers of girls. When we read that her mother had been waiting for her, patiently, in the dark, just feet from the place where their neighbor snatched her away forever, the chill ran through us from head to toe. When we saw her mother’s face in the paper, her eyes over her mask as she stood, arms crossed, watching the killer as he was escorted through the halls of the Judicial Branch, we felt it again. This whole, small country had a knot in its stomach, a nausea.

I am sorry to say that I didn’t know the word “intersectional” until after the 2016 presidential election in the United States. That’s when I started to learn about the times when white feminism failed to connect to other struggles for justice. I started to learn about the idea that while each struggle is different, that while you can’t compare Costa Rican femicide to the ruthless murders of Black citizens of the United States at the hands of the very law enforcement officers who should protect them, you also can’t care about one without caring about the other. I learned that, in our brains, we must make room for all these movements, rising, to converge.

Many of us live in the consciousness of both those realities, the U.S. context and the violence against women in Costa Rica. Many of us understand this intersection between Allison and Breonna. Between María Luisa and George. Between those chains of victims’ names – awful, relentless, ever-expanding – and the worlds they represent. Between the discussions these deaths have started, over and over, and of which we are so profoundly tired.

There is a recipe for it, a dance that’s pre-choreographed. In Costa Rica, when it comes to femicide (femicidio, the murder of a woman because she is a woman) the recipe looks like this. The victim’s name becomes a hashtag; women put filters on the profile pictures with heartbreakingly simple assertions like “We want to live”; some men put up posts like “nací para cuidar a la mujer”—I was born to take care of women; women try to explain that we don’t want to be taken care of, thanks, just not murdered; other women criticized those women for never being satisfied, for trampling on those nice men’s nice gesture, for being so hard to please; and still other men publish, “We get murdered, too.” Women aren’t the owners of pain. All lives matter.

These are currents that push back and forth against each other, washing back and forth, sad and angry, wise and foolish. They are the same kinds of currents that wash back and forth in my own country surrounding racial injustice. All the while the victims lie beneath, among the smooth stones on the riverbed, unknowing, unseeing.

It is all so foolish, and it goes nowhere. We keep on losing. The stones keep dropping through the water, the next name, the next hashtag. The next life snatched away from a mother standing watch. At times, we just want to sink down there with them: not for death, but just for silence.

How do we rise out of the water altogether? Into the air, gasping for breath? Breath. A loaded word—and doesn’t that say it all, the fact that breath is a loaded word? The breath that has been denied, so ferociously, to Black women and men in my country, who are required to live in fear not only of random strangers but also of those who are supposed to protect them. The breath that a different kind of blind hatred and contempt choked from María Luisa in Manuel Antonio, another victim of femicide in Costa Rica, 2020.

What pulls us out of the water is love.

I think I first fell for the sensations of this country: its sounds, its sights, the way its air felt on my skin. Later, I fell in love other things about Costa Rica. But my latest love affair has been with the women who live here. The artists and scientists, the activists and authors. A group in which I include myself, through presence if not citizenship. I pour the past 16 years and my deep admiration for the women of this country into a proud, tentative “we.”

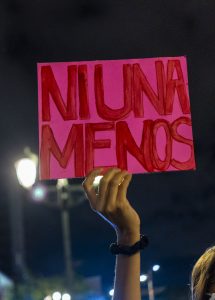

We, the women who live their lives in this land, are extraordinary. And we are being murdered in such quantities. We march, we post, we mourn, and, somehow, with Allison, we reached the end of our breath. The wind has been knocked out of us. We ask, what else can we do?

The answer, perhaps, is: nothing. Just as the burden of anti-racism should fall on white shoulders, and the burden of ending homophobia should fall on those who are straight, it is up to the men of this country to figure this out.

Not to take care of us. To take care of yourselves, in the toughest sense of that phrase. The sisterhood is in place. It’s time for the brotherhood: a brotherhood of self-questioning, of raising the bar, of pushing back against each other as Vinicio Chanto outlines here.

As you do the work, your sisters will continue to disappear. Disappear. Just hearing my daughter say that word made my heart contract.

What hurts the most, I think, is the knowledge that while, for now, I can keep that fear within myself, a sort of poisoned apple in my heart, I will have to share it with my daughter as she grows. I will have to hand it to her for her to try, nibble by nibble, taking that poison into herself so she can protect herself.

When I was in seventh grade in Dunbarton, New Hampshire, I’d sometimes be dropped off before anyone else was home. I’d put on some boots and take our dog, Max, into the woods behind our house. We’d walk around, muck about, sometimes go as far as the dike that stretched high above the wetlands. I don’t remember anything too specific from those walks: I wasn’t learning the names of all the trees and plants, or building forts. I don’t remember any fear or worry about wandering on my own with a dog who wouldn’t hurt a fly. I just remember the space, the cold inhale in winter, the slushy mud in early spring, the look of the wetlands glinting through the trees.

My daughter won’t have afternoons like that. I hope she won’t walk alone late at night as I did during university, either. I don’t think she’ll travel alone quite as widely and freely as I did. She will be robbed of something I once enjoyed through my privilege as a white person and my ignorance about the dangers facing women. What’s more, I will be the person who robs her of it, by instilling in her a necessary caution.

I will take it from her bit by bit in the talks that will fall to me to lead, the precautions it will fall to me to teach her. I will steal from her what has been stolen from me. I will rob her of her innocent aloneness, her privacy, her ability to feel free and safe all by herself, to walk where she likes without a thought, to stroll the woods without a care, to go home from a night class on the town bus without stepping into a heavy legacy. I will rob her of certain chances to nurture that space between her ears, the unencumbered breath in her lungs.

I will be the thief, but I will not be at fault. I will teach that to her, too. I will teach her the power of boundaries, of analysis, of assigning blame where it belongs and deflecting it where it doesn’t, deflecting it along with the blows of an assailant. At her side, I’ll learn how to throw a punch and gouge out someone’s eyes. I will have to raise her powerful, confident, strong, and angry. Because if she looks at this world as it is and doesn’t feel anger amidst all the other emotions – all the love, gratitude, excitement that I hope she’ll also feel – then I won’t have prepared her well. Anger on her own behalf. Anger on behalf of others.

What do I have to offer her in exchange for all this taking? A voice she can raise at a moment’s notice. She will have the possibility to connect to other women anywhere in the world. When we got home after our walk in the mists, I watched Alexandria Ocasio Cortez show us her morning makeup routine. I was right there with her, in her bathroom, learning how she creates her signature red lip. This YouTube mix of color corrector and commentary on the patriarchy dropped into the jangling chords of my mood in a strange way.

I thought: it is a consolation prize, I suppose. This community. This sisterhood. Perhaps it is not something we can touch, women we can see in the flesh, but they are out there, and we can hear from them.

Is it enough, these virtual connections in the face of all that we lose in terms of physical safety? Is it enough, being able to scream any way we want, scream and rail and testify?

Will it get us through while our brothers fix what’s ailing them?

It will need to be. Our daughters will have to make it so.

Your. Writing is liquid gold. Golden apples, as well as poison ones.