“The answer is in the Blue Zones,” one Instagram user commented when we asked about the secret to healthy aging. Is this true?

Since 2007, when the Nicoya Peninsula was included in the list of the world’s Blue Zones in the world—areas with disproportionate numbers of centenarians—many people have carried out studies to find that answer. The U.S. journalist Dan Buettner, who encapsulated those early discoveries in a series of publications for National Geographic and later in his book, “The Blue Zones,” says that the dietary secrets of long-lived Nicoyans include drinking water with a high calcium content, eating a light dinner, and consuming tortillas and beans.

But is that all there is to it?

The short answer is no. Although tortillas and beans are part of the nutritional secret that allowed healthy aging in Nicoyans who live beyond the age of 90, there is another very simple element that has become less common in Costa Rica in recent years. Its absence has begun to have an impact on the health of all Costa Ricans—an impact that specialists continue to research.

One of these efforts is a series of research projects led by the University of Costa Rica (UCR) in the Space for Advanced Studies of the UCR (UCREA). That’s where specialists in nutrition, microbiology, demography, social work, food technology, and other subjects are conducting research so they can better understand what the nutrition and everyday life of these long-lived people can add to our daily lives to promote healthy aging.

The findings of this study have not yet been formalized, but they already suggest that what needs to be done at the nutritional level is actually fairly simple.

Health and nutrition in Costa Rica

“Overweight and obesity are leading risks for global deaths,” says the World Health Organization (WHO). Why? Because the poor diet that sometimes leads to being overweight or obese has a direct consequence: the development of multiple chronic noncommunicable diseases that not only cause death, but also lives and sick aging. Those diseases can include diabetes, cardiovascular illness, and some cancers.

Costa Rica’s reality is not far from the WHO’s general picture. In 2016, according to the WHO, 39% of adults over the age of 18 are overweight and 13% are obese. In Costa Rica, according to the latest National Nutrition Survey carried out in 2008, 35.3% of women between 20 and 64 years of age are overweight ,and 31.3% are obese; meanwhile, 43.5% of men in the same age range age are overweight, 18.9% are obses.

According to Georgina Gómez Salas, nutritionist and researcher of the UCREA interdisciplinary research project, these results are old, but they already showed a trend. Obesity has been proven to have a direct effect on people’s life expectancy. In 2014, the US National Institute of Health reported that obesity can shorten life expectancy by up to 14 years.

Today’s diet in Costa Rica: fast and homogeneous

Between 2014 and 2016, a Latin American Nutrition and Health (ELANS) was carried out in urban areas of eight Latin American countries, including Costa Rica. This study seeks to help researchers understand Latin America’s high obesity rates, and revealed how Costa Ricans eat in urban areas.

Part of the analysis reveals that the diet of Costa Ricans “is characterized by a high consumption of coffee, bread, white rice and sugary drinks, and an insufficient consumption of legumes, fruits, vegetables and fish.” Some of the recommendations generated through the study were to improve nutritional education so that Costa Ricans are better prepared to select food. However, it noted that it’s also essential to ensure accessibility and availability.

According to the research, Costa Ricans in urban areas consume at least five of the nine food groups established by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) on a daily basis. However, the consumption of some of these groups, such as fruits and vegetables, does not reach half of the recommended daily amount. In addition, the study observed “an inverse relationship between dietary diversity and conditions of excess weight, abdominal obesity, and cervical obesity.”

Good news: urban Costa Rica showed the highest consumption of beans and legumes in the eight countries studied. This is a group of foods known for its beneficial effects on health.

At the regional level, the study determined that only 3.5% of the people interviewed ate enough seeds, whole grains (or integral), fish and yogurt.

So, how is the diet of Costa Ricans today? Without an up-to-date national nutrition survey, nothing can be guaranteed, but studies like ELANS show that it is very likely that Costa Ricans eat homogenous foods and are gaining weight. That can only have negative consequences on health and aging.

How does the diet of Costa Rica today compare with that of the long-lived people of Nicoya?

“It was a more natural diet. Now, we eat more processed foods,” says Georgina.

Yesterday’s diet in Costa Rica: the solar

Romano González Arce is a nutritionist with a master’s degree in anthropology. He belongs to the research team at the interdisciplinary UCR project. In his research, he has focused on understanding and learning more about the eating habits of Costa Ricans throughout history, with special interest in the Nicoya Peninsula.

“You have to study beyond the present,” says Romano. “Today’s diet could be different than it was 50 or 70 years ago.”

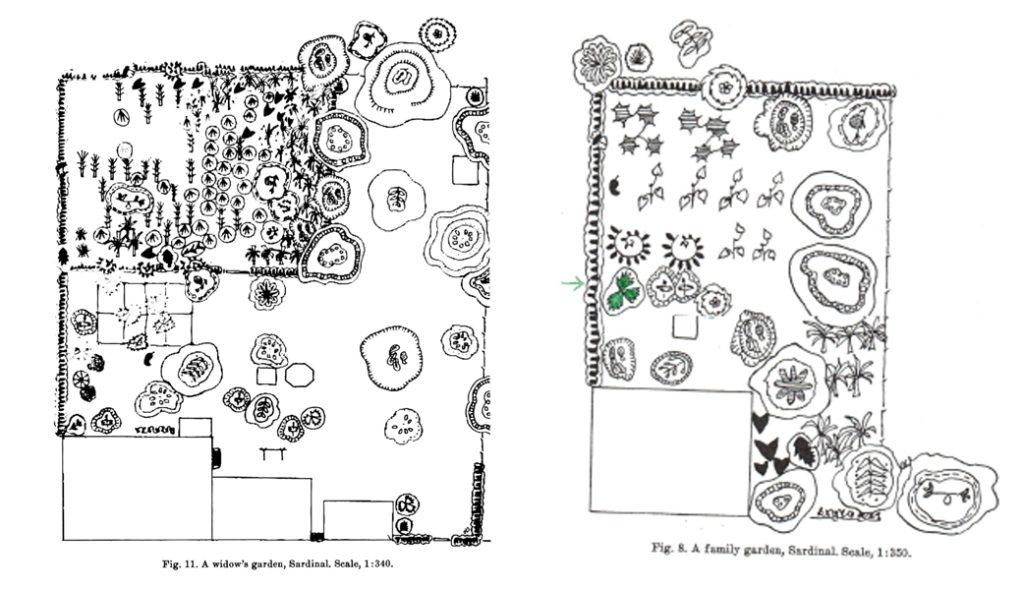

In “Nicoya, a cultural geography”, the geographer Philip Wagner describes in detail the lots of Nicoyan houses in the 1950s—that is, the patios around the house, where there was a great diversity of food.

“The solar, the traditional tropical vegetable garden, is a miniature forest,” says Romano. Access to this nutritional forest marks a difference between the eating habits and realities of our population in the last 70 years. Romano explains that this type of extended garden with many different plants was not found only in Nicoya, but also in many places in Costa Rica and America. He adds that this type of gardening is part of our indigenous heritage and that it can still be seen in many indigenous communities in Costa Rica—but not so in most of our homes.

“There are no living fences anymore. There are no longer [garden] lots: now they are gringo style, with grass and flowers, or they are monocultures”, says Romano.

When Wagner describes the small gardens, the list of foods grown there is long: cassava, tiquisque, ñampi, yam, sweet potato, ayotes, pipián, pumpkin, cucumber, paste, chayote, watermelon, melon, cucumber, plantains, many types of bananas differing in size and flavor, sweet and hot peppers, quelite or chicaquil, and a large number of fruit trees such as guácimo, jícaro, guava, annono, cashew, papaya, sapodilla, medlar, avocado, and carao.

Many of these names and products have already been forgotten by younger generations.

In addition, these “nutritional forests” also had fauna Chickens and pigs were very common. There were also turkeys and ducks, and they grew honey from native stingless bees kept near the houses.

This is how Nicoyan tables contained tremendous food diversity, as well as the basic foods consumed today throughout Costa Rica.

“What was standard was corn in tortilla form, rice, beans, some meat that could have been fresh or dried over the stove—but not in large quantities,” says Romano. “They accompanied this with what they will find there [in their gardens] in season.”

“There was no concern about eating well, but everything that was there was fine,” he adds. “The variety and quantity was not a concern. There was a constancy in terms of nutrient supply”.

Romano planned to conduct interviews to studyt the eating habits of the long-lived Nicoyan population in greater depth, focusing on the past: what did they eat when they were children, young people, adults? However, the COVID-19 pandemic did not allow it. In the meantime, the bibliographical research he’s conducted has allowed him to generate many hypotheses.

“There is a [decrease in quality] in terms of diet probably linked to deforestation, which must be studied,” he says. But he adds that “this research has to do the same exploration with the grandchildren or great-grandchildren of centenarians.

“Everyone knows that [food] is not the same, but you have to show it,” he says. “In Costa Rica you have to explore the old with the young [from Nicoya]. In theory, they have the same genes.

“There is a very strong genetic component, but the genes take care of themselves,” says Romano. “Everywhere, young people and adults know they are eating poorly and continue to do so.”

So what should I eat to age healthily?

The simplest answer is: diversity.

“Nutritional diversity, because the more foods we involve, the more we ensure that we are meeting [nutritional] requirements,” says Georgina. She also adds that it’s important to eat the right portions to avoid becoming overweight. “The diet has to be varied every day.”

How do I achieve food diversity? Georgina recommends, in addition to the foods we are used to eating—such as rice, beans, red and white meat, dairy products, eggs—increasing the consumption of fruits and vegetables; being aware of eating green leaves such as spinach, orange vegetables such as ayote; and making an effort to include whole grains and seeds, such as brown rice and whole grain crackers. She also recommends eliminating white flours in products that are full of sugar: “don’t make that your everyday bread.”

Georgina’s not alone in giving this advice. Many studies that have shown that through nutritional diversity, we can not only increase our odds of eating the correct amount of nutrients that our body needs, but also increase our antioxidant intake, and reduce our risk of cardiovascular disease and other illnesses such as diabetes.

The long-lived people of Nicoya had a pretty simple answer to the question of what to eat to age healthily. The danger is that, like the vast majority of Costa Ricans, they are no longer doing it.

“The lifestyle that the newer generations already have does not guarantee that by living in Nicoya they will live 100 years,” says Georgina. “Lifestyle has changed, food consumption has changed. You see it in the clinic in the physical condition of people. They are no longer healthy enough to provide for a good old age.”