“The cruel reality was that there were no books and there were no libraries. It was like a bucket of cold water,” says Alda Cañas. “How do you learn to read if you don’t have a book? It’s like learning to swim without a river, without a pool, without the sea.”

Since 2014, Alda has been one of the partners of GUIAREa social enterprise founded in 2009 by Victoria Coronado to provide training for teachers in the public and private sectors.

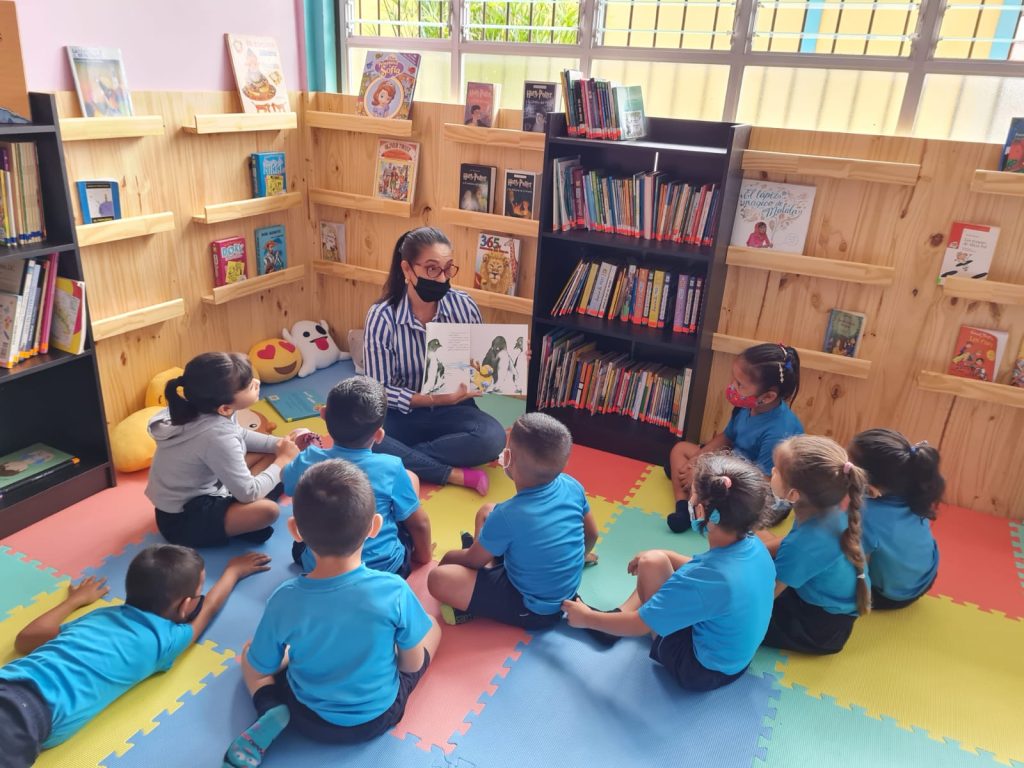

In 2017, after three years of preparation and approval by the Ministry of Public Education (MEP), the GUIARE team began a series of training sessions for preschool teachers that sought to support them in the implementation of the new MEP curriculum approved for that level in 2014.That curriculum included the suggestion to create spaces for daily read-alouds to children. The first GUIARE courses were given in the province of Limón, which is where the team was first doused with the cold water Alda describes.

“Our first question was, ‘How many books do you read to your students?’” recalls Alda, who says the general response was: “No, we don’t read to them. No, we do not have books in the classrooms. No, we don’t have libraries.”

As Alda and Victoria, who are teacher trainers with experience as private school teachers and principals, continued to teach their workshops, they discovered that this reality was not unique to Limón. They saw it in San Carlos, and then in Guanacaste.

“The answer was always, ‘We don’t have books,'” says Alda. “They are children who do not have books at home. So [if there are no books at school], you don’t have access to books at all.”

That’s why in 2019, in a decision she describes as impulsive, Alda announced to the principal of the Jaime Gutiérrez Braun School in Cañas, Guanacaste, that she was going to give him a library. This became the first “Biblioteca Actualiza,” as GUIARE came to call its donated libraries. (“Actualizar” means “to update” or “to upgrade.”)

Between 2021 and 2023, eight more libraries were inaugurated—now organized through the Actualiza Association, a nonprofit organization that channels GUIARE’s corporate social responsibility work. Three more libraries are underway.

Without books or other resources, there’s no reading

The State of Education 2021 Report states that, as of 2019, only 16% of public primary schools have a library. Of the 593 schools that this percentage represents, half are in the Greater Metropolitan Area (GAM).

The report also states that users surveyed about these libraries rated them as just “regular… in relation to infrastructure, accessibility and resources,” and 66% have one or fewer books per student. Only 12.5% say they have more than 10 books per student, despite the fact that the MEP establishes a library minimum of six books per student in first cycle (first-third grade) and nine per student in the second cycle (fourth-sixth grade).

Lisbeth Arce Wrong, Director of the MEP’s North-North Regional Directorate of Education, says that there is “a great need” for school libraries but a lack of resources to create more of them.

“The MEP has a fairly limited budget,” she says. Libraries “must be prioritized, but school libraries aren’t a priority when there are serious infrastructure problems and other basic needs.”

“Books are a big investment… In the end, [the system is] elitist, because not everyone has access to top-quality books,” she says.

For this reason, the Actualiza Libraries that now exist in seven North-North schools have made a difference, according to Lisbeth.

The Actualiza Libraries

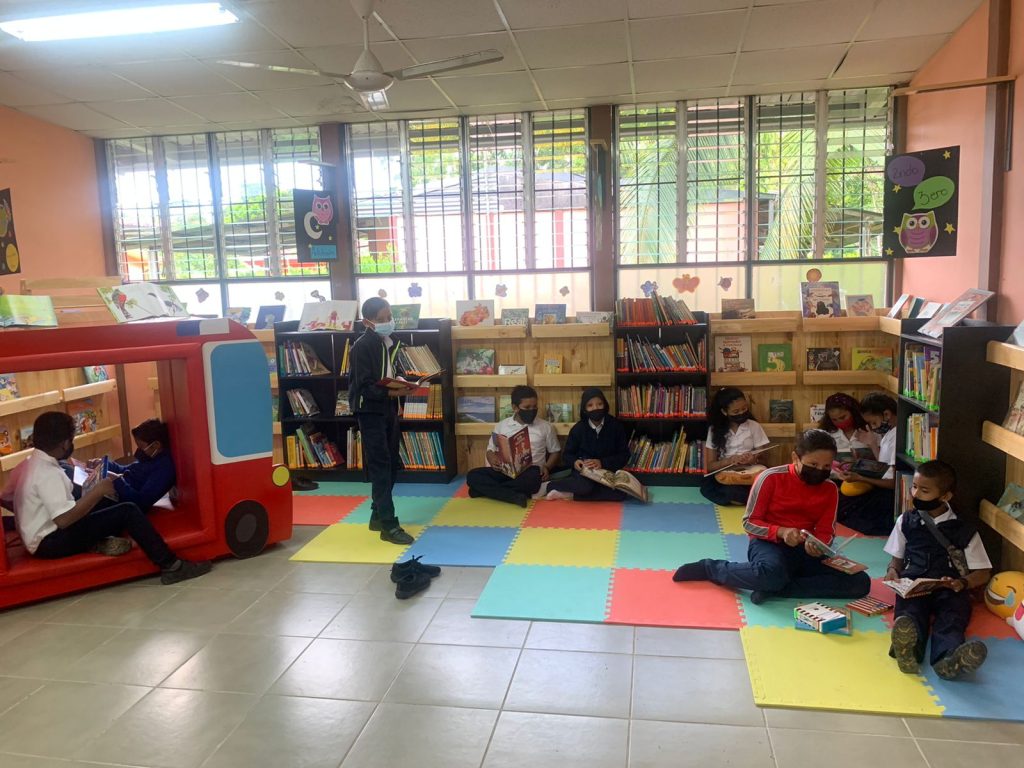

Each of the Actualiza Libraries has at least 900 books—mostly donated—classified into five categories that include first and second cycle. The entire library is delivered with a spreadsheet that includes categorized information for each book. The donation also includes shelving, puppets, cushions, rugs and a table, so that the space is “cozy and invites reading,” Alda says.

The nine libraries that are in operation to date comprise 7,892 donated books and have served more than 800 children, an amount that increases each year with the entry of new preschool students. Alda and Victoria expect the lifespan of these libraries to be very long, allowing the number of students affected to rise over time.

“As long as the principal, teachers, and children take care of the books, they should last for many years,” says Victoria.

“We also [donated] class sets,” she adds. “We give them six copies of the same book, two titles per grade [from the MEP’s recommended reading list], so that the teacher can check out those six books, take them to the classroom, and use them for various activities.”

The class sets are a recent effort, but have already been added to all existing libraries. The association is also conducting workshops with the teachers of each of the participating schools called “The Library: A Magical Place,” to promote the use of these resources.

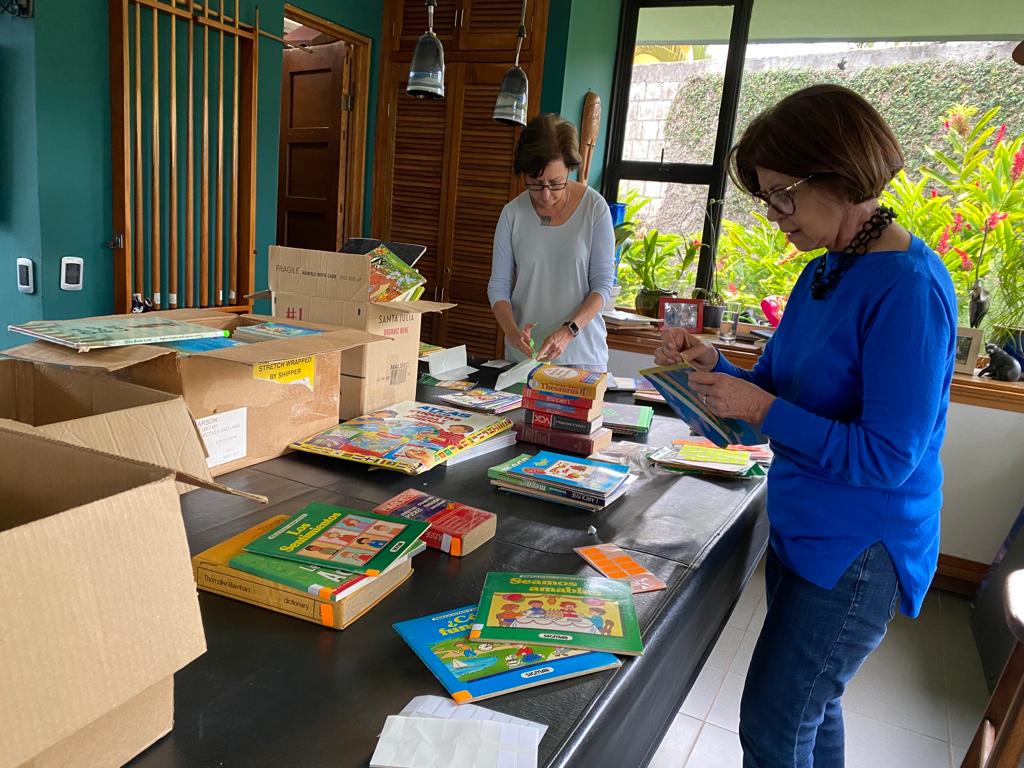

The Actualiza Association receives donations in various formats, from furniture to volunteer time to curate and prepare the books for each library. As they do this work, they look for the schools that will receive upcoming library donations.

“This all takes time,” says Victoria. However, for both her and Alda, this is not the biggest limitation of their project.

“What we need are books. Books are very expensive,” Victoria explains. This is a comment many people have made to El Colectivo 506—not only people interviewed for ¡A Leer!, but also from parents and educators on our social networks and in our WhatsApp community Education 506.

“We need all the children who have already read those books and are no longer going to use them to donate them to us,” says Victoria. “We wouldn’t give enough if we had to buy books from a library”, says Victoria.

Donating is as simple as “calling GUIARE to coordinate delivery,” says Alda, to the numbers (+506) 8827-9927 and (+506) 8331-1100.

However, she also clarifies that donations cannot be just any type of book. They must be children’s books. GUIARE has received calls from people who want to donate libraries that belonged to adults, but these are of no use for the schools. On another occasion, they received a donation of books about healthy snacks, but that wasn’t helpful either because rural students get their food at school and don’t bring snacks from home.

However, Alda stresses that the secret of the Actualiza Libraries is “not just boxes of books, but the whole library, including the shelves, the facility.” That’s why monetary donations are also important: “When you go to rural schools, you realize that they do not have bookshelves. You have to start by giving them the environment and the ease of implementing and using it. It’s a libraru—it’s not just books”.

That is why, when they select the schools that are going to receive a library, they establish requirements.

“We are looking for a committed principal who sees the importance of it, who is involved and who takes care of [the books],” says Alda. In addition, the school must have between 80 and 100 students, in order to achieve the density of books recommended by the MEP. It must have a classroom available where the library can be installed with certain minimum conditions such as a ceiling, windows, and a fresh coat of paint.

For Lisbeth, these requirements are a limitation. In the region that she directs, there are many schools that exceed 125 students. In addition, school infrastructure is often insufficient or in poor condition, which means that each community must organize and invest in their school in order to prepare the classroom where the library will be installed.

“I would like all the institutions in the region to have these resources, but we know how expensive they are,” says Lisbeth. “Each library is valued at more than ₡10,000,000.00,” or approximately $18,500.

What’s it like for a rural school to get an Actualiza Library?

Darling Lopez González is the principal of the Jesús de Popoyoapa School, an institution with 151 students enrolled in 2023. To serve these students, the school has a preschool teacher, three first and second cycle teachers, and one teacher each for English, computing, religion, and special education. Popoyoapa is a community in Upala dedicated to agriculture and livestock. The school is the town’s only public institution.

In November 2021, the school inaugurated its Actualiza Library.

“Really [the library] was a great blessing because in most public institutions, we have many problems with reading comprehension. It’s because of a lack of reading,” says Darling. “ANow, we already have children who have picked up the habit of reading. As time has passed, reading habits have grown more and more.”

For example, during the week after International Book Day on April 23, the school took advantage of the library to carry out a reading plan where each teacher prepared special reading activities with each of their groups.

“Our colleagues are very committed. I asked them to make me a reading plan, and all of them this week have been doing a reading project,” says Darling.

However, she explains that the greatest benefit from the library was achieved in 2022, with the appointment of a preschool teacher to manage the library. This person facilitated the work of the teachers in the library; according to Darling, teachers scarcely used the resources when there was no person in charge of it, because of the work involved. Monitoring the checking out of books and keeping the library organized is another duty for teachers who, Darling says, “are already overloaded with an endless list of tasks” outside of the classroom, such as committees and other programs.

In 2023, it was not until the end of April that the institution again managed to appoint another person to this position.

For Darling, the community impact is still a work in progress.

“It has been very difficult to protect the library. It’s been a slow process with the kids,” Darling says of borrowing the books to take home. “There isn’t that culture in the homes of taking care of and returning the books. We have lost some books.”

However, the principal says that the value of the library for the institution has led them to obtain more book donations. From the 789 books they received in 2021, they have already increased to 964.

Elizabeth Rojas is the principal of the La Cabanga School in Guatuso, Alajuela, an institution that received an Actualiza Library in May 2022 with 914 books. For Elizabeth, the donation of the library was a form of recognition of the work carried out by the community, student population and teachers in 2021 to beautify the institution and fill it with learning activities.

Today, the institution has 64 students, and nine staff members including four teachers for preschool, first and second cycle. Like Popoyoapa, Cabalga is a rural community dedicated to agriculture and dairy farming. It is also home to many people who work in public institutions in Guatuso.

In addition to being the principal, Elizabeth is also the fourth grade teacher. She says that in her experience, the library has been very valuable. First, it allows teachers to access a permanent resource that they can plan around. Second, it provides resources they can turn to when their existing plan falls through because, for example, there is no internet at school that day.

However, like Darling, Elizabeth believes that teachers could get more out of the resource if they had a librarian. Otherwise, teachers must use lesson time to organize books after using them with students, or when students ask to borrow books.

Despite this, Elizabeth and the other teachers continue to use the resource: for the students of Cabanga, the library has become a small oasis of comfort and opportunities. In fact, many students prefer to go to the library instead of playing during recess.

“The space has a lot to do with it: the fact that there is AC, a big carpet to sit on, adequate furniture. The fact that the classroom is painted in a fresh color. That helps a lot. When they’re in there, [the students] see books and say ‘Look, we haven’t seen this one, let’s read it,’” the principal says.

Elizabeth and the other teachers have also decided to take advantage of the space to implement the 20 minutes of daily reading recommended by the National Plan for the Promotion of Reading and the MEP’s I and II Cycle Curricula..

“I think [the library has helped to promote reading]. With my experience, that I take them every day, for them it is beneficial and for us it is a very useful tool”.

“[The Actualiza Libraries] have had a positive impact on the student community of these educational centers,” says Lisbeth as director for the North-North region and ensures that in the visits made by the specific advisers of the Regional Directorate to the institutions “in order to accompany them in the educational process and determine the progress in the reading-writing processes and in these institutions [with Actualiza Libraries] there are higher levels of achievement.”

“The teachers themselves have stated that it has motivated them to have these resources that allow them to stimulate students and parents as readers,” says Lisbeth.

“It is a process that transcends the learning process in the classroom, because the children have the option of taking the books home. Reading is encouraged at the family level, and in an area like ours, with low-income families, it is the only opportunity to have this type of material.”