Today, in a cyber world based on analog codes where immediacy is the greatest truth, family culinary heritage—that intangible heritage collected in ancestors’ notebooks—is its own kind of wealth. Some of these traditions are not hidden away in a remote corner of the kitchen, but proudly showcased: vintage wines, or porcelain and glasses inherited for generations.

That book of culinary secrets, or that tin jar, or that picturesque sugar bowl that’s now used as a vase, are all part of history. It’s a history that belongs not only to the family, but also to society.

That can of exquisite tea from China, or of English biscuits, crossed the sea by ship for long months until they reached our Costa Rica. The containers became useful to a grandmother, great-grandmother or mother to store the coffee beans from the home garden and grind them when the family gathered for family celebrations, or after the evening rosary. That was the perfect moment to talk about cooking and ask how to prepare the biscocho, pan de naranja, or pan batido that were offered with that coffee.

That’s when, from the mouths of grandmothers, aunts and cousins, the recipes for the dishes issued forth: the culinary secrets that give rise to family cookbooks.

At any point in history, even today, this is something that transcends social status, educational attainment, the urban-rural divide. For generations, families of all kinds have passed down secrets, properties, silverware, facts, books, and jewelry that help them recognize themselves as part of a group, and understand that they didn’t spring up from nothing. If physical traits such as the eyes, mouth or hands are inherited from a grandmother, a great-grandfather or another blood ancestor, then we also inherit our way of preparing food.

This inheritance does not only concern women. Today, men have entered the kitchen. An example is television programs, where Argentines, Italians, and Mexicans share their inherited culinary secrets. The most sophisticated chefs show off their family recipes.

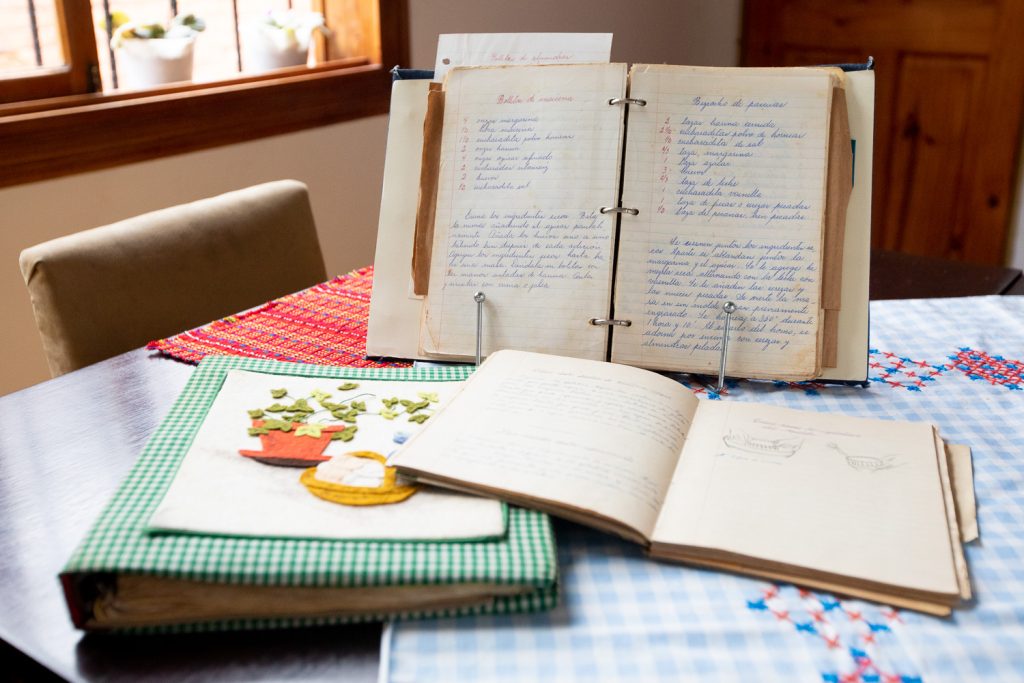

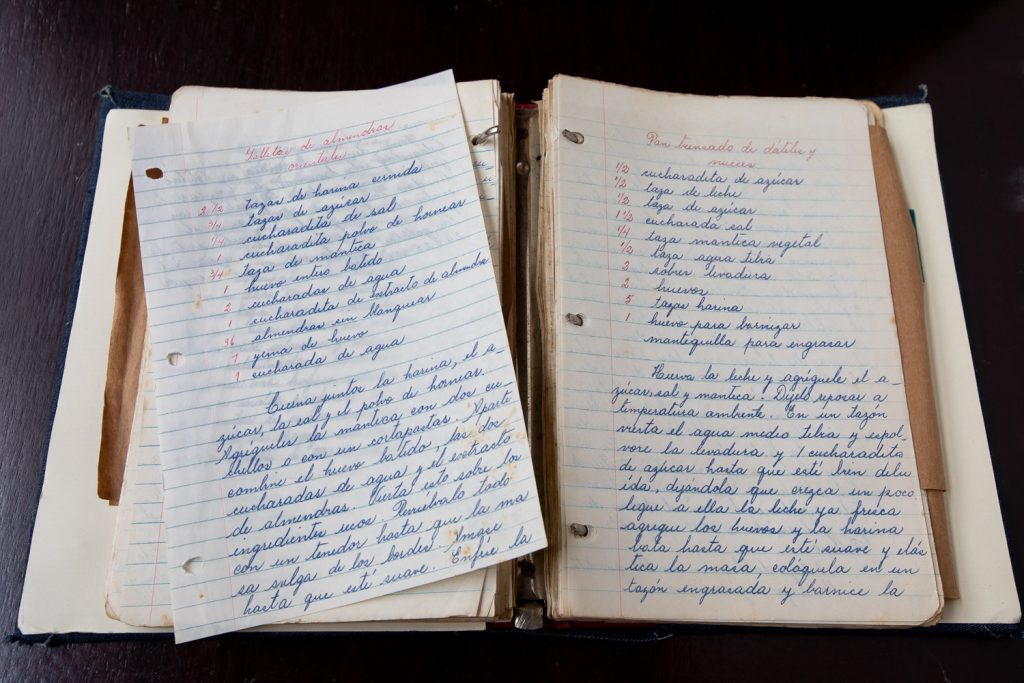

This is how the culinary art came to be zealously preserved in those ancestral recipe books, passed from hand to hand, or given by a mother prepared to her daughters or granddaughters when they began their family life. These resources are appreciated today with great pride and grace.

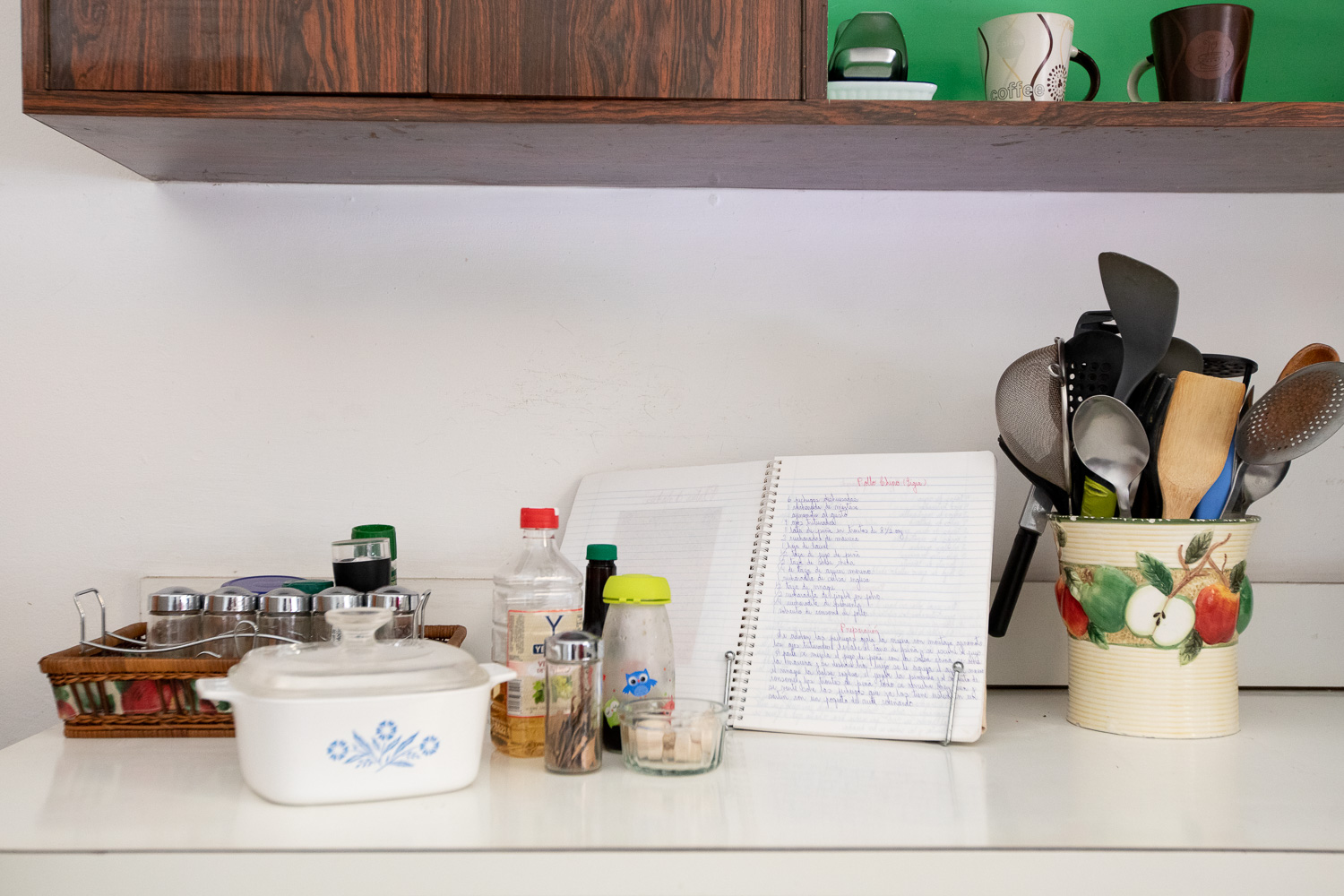

The secrets of the kitchen of yesteryear, locked in notebooks and loose sheets, have brought to life the kitchen of today’s family—as well as new businesses in Costa Rica.

Repositories of culinary secrets

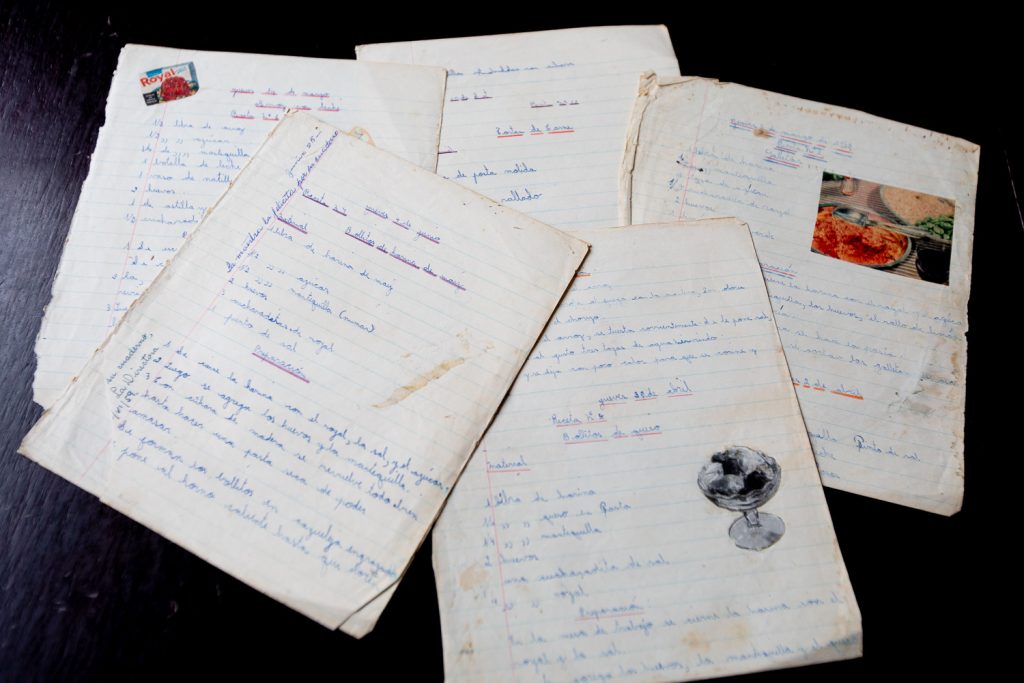

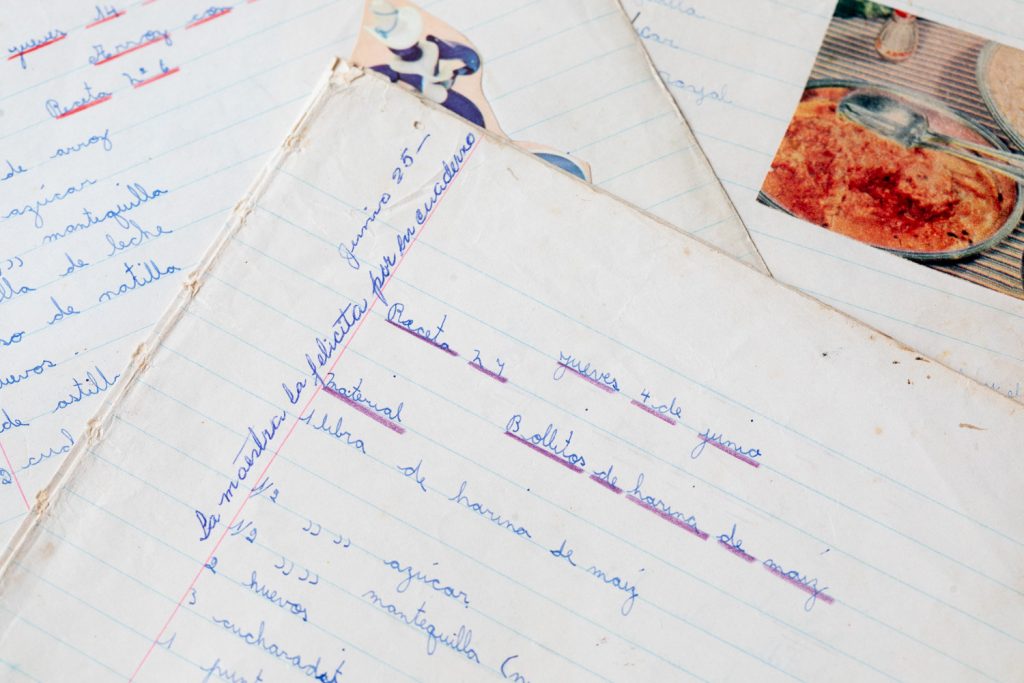

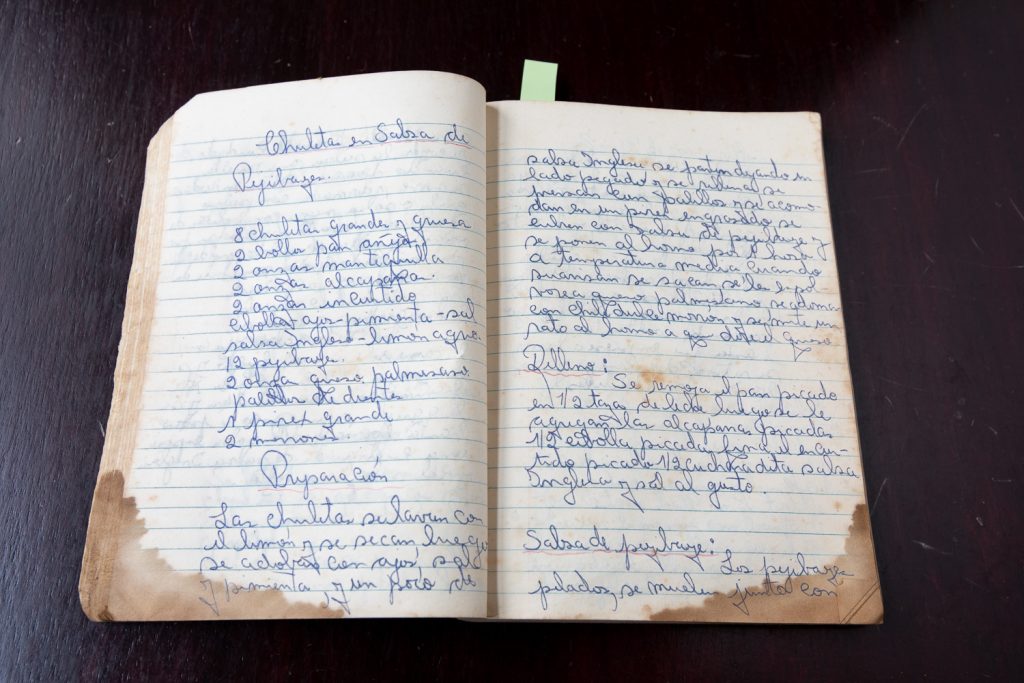

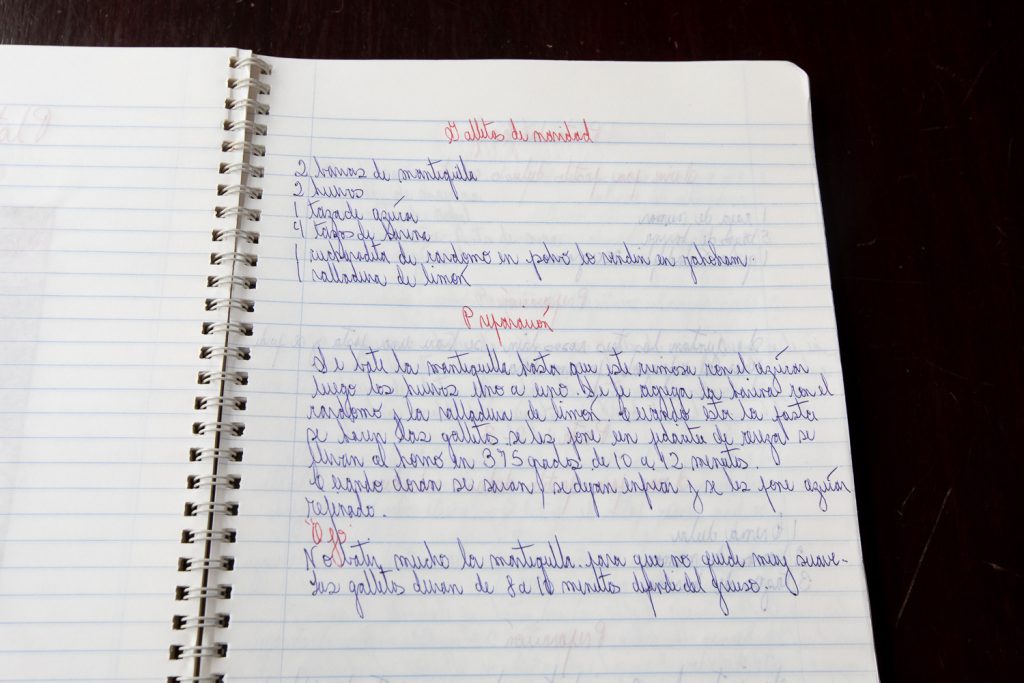

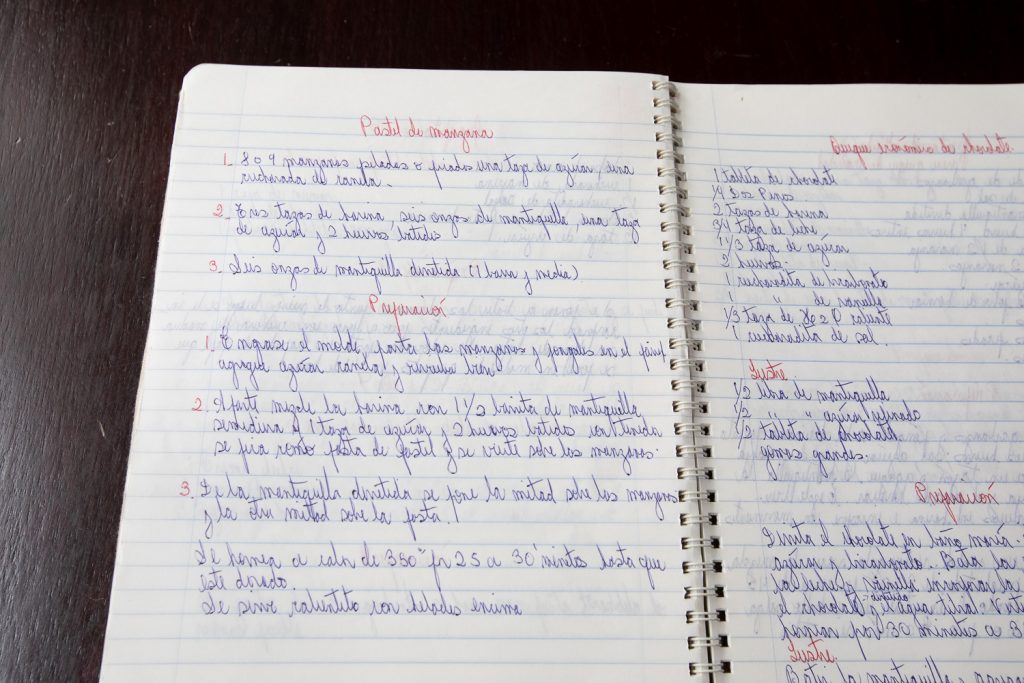

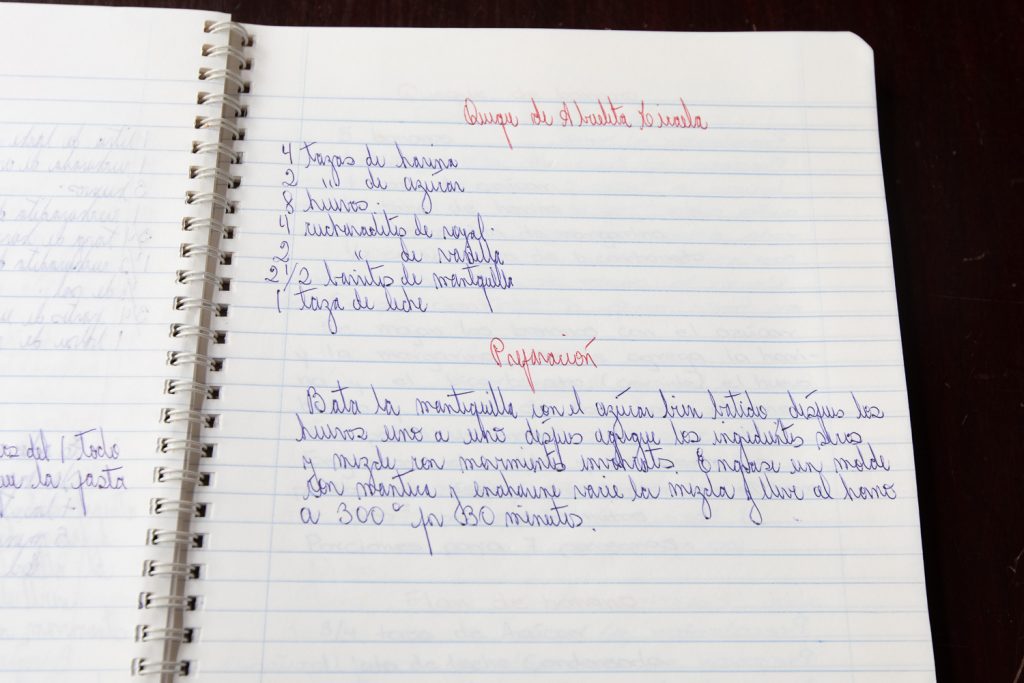

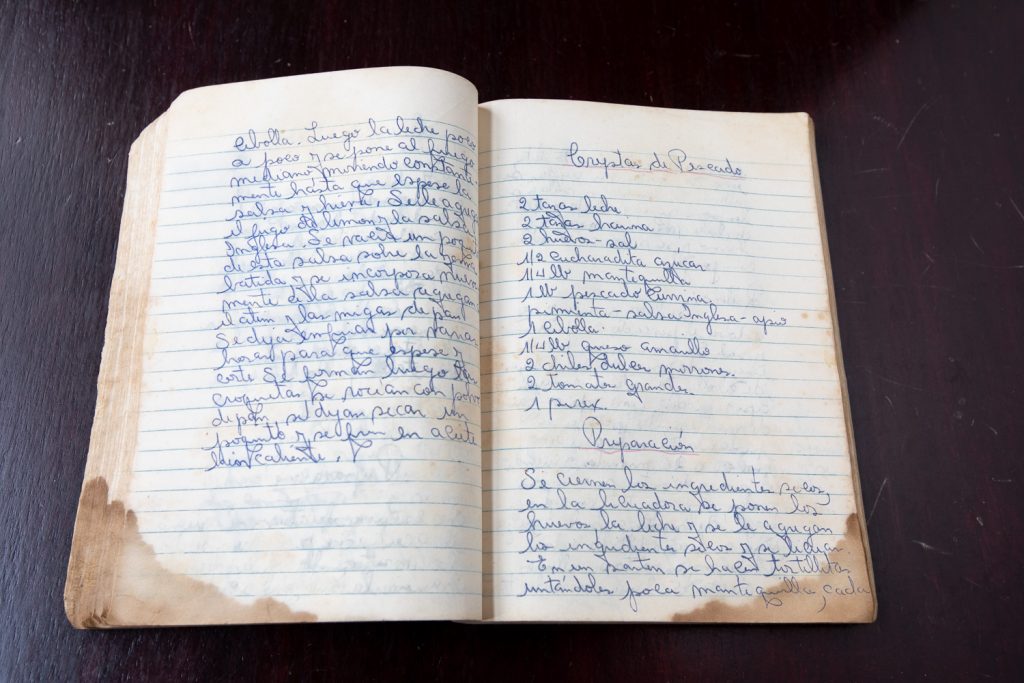

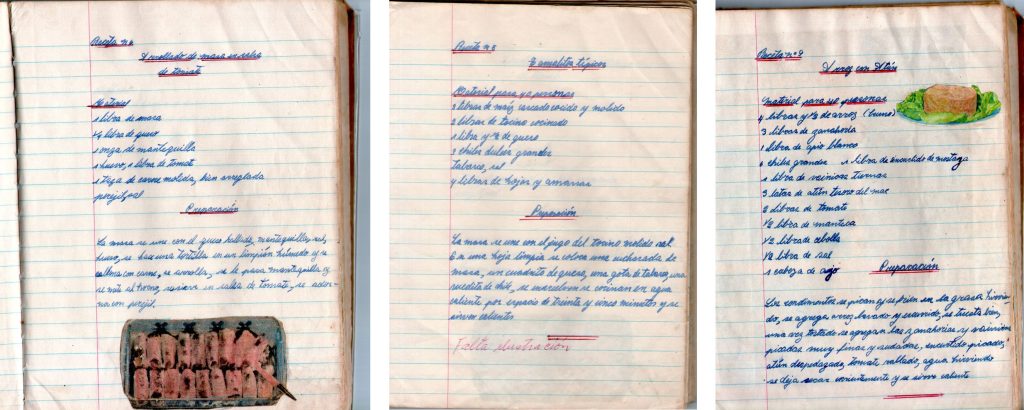

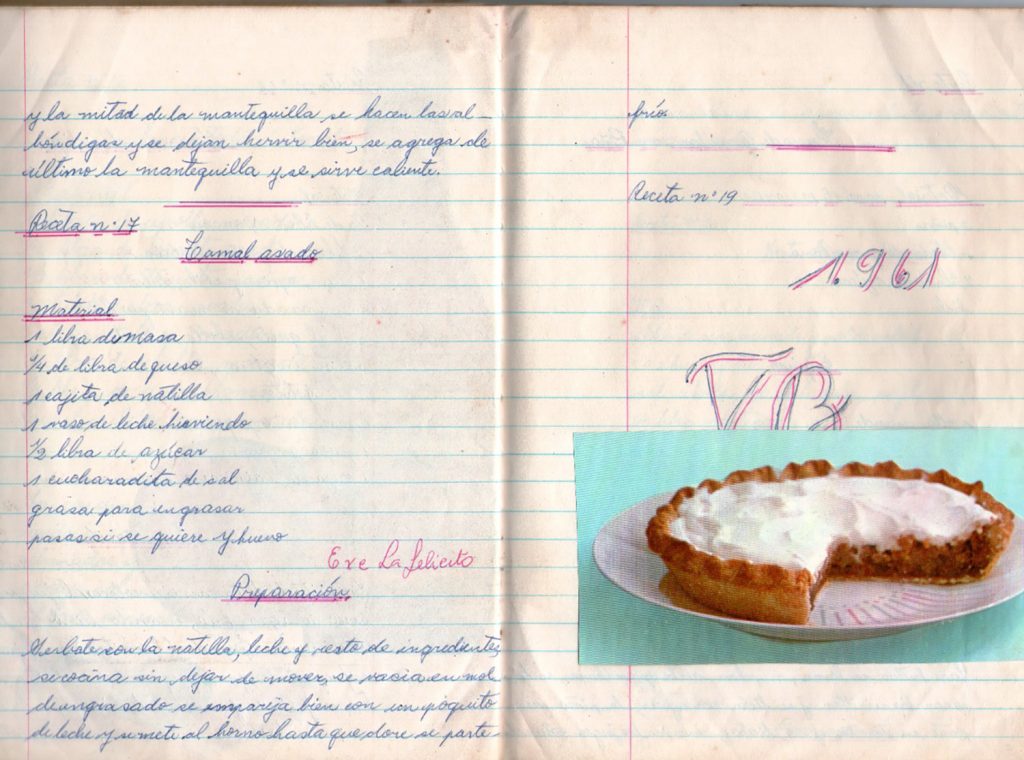

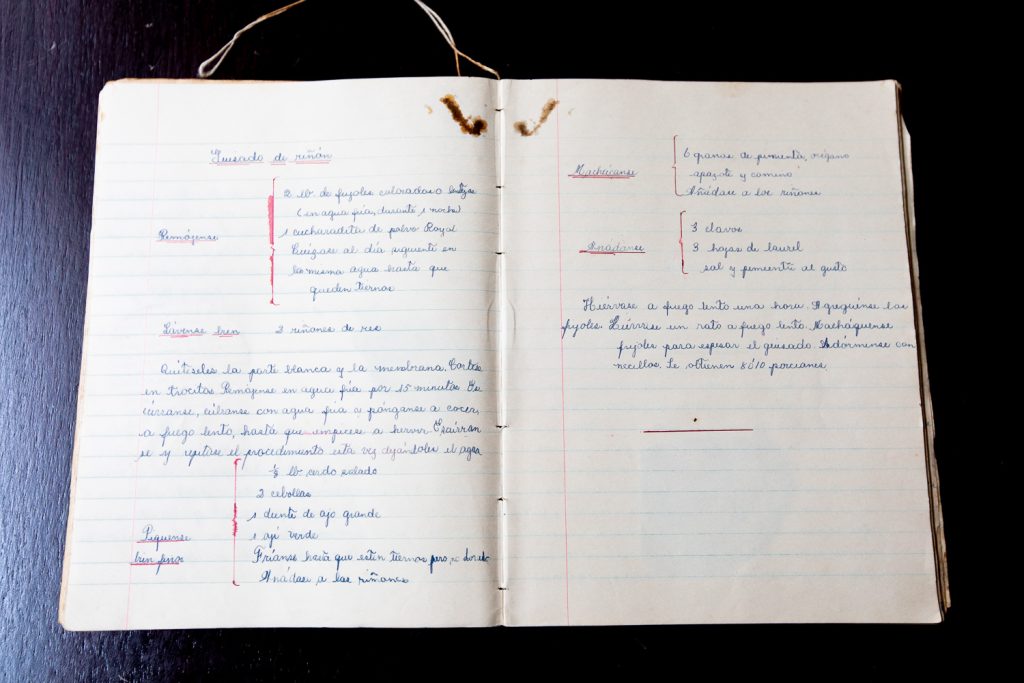

I have compiled several cookbooks from various contacts and friends. Some are very well cared for; others are a handful of loose leaves. Others are stained by a wayward ingredient during the preparation of a dish. All all handwritten in childish hands, some of which change as their authors grow. Some have magazine clippings alluding to this dish or that. Another is inscribed with a congratulatory message from a teacher and school principal.

Going through these culinary treasures leaf by leaf, I have found as a common thread, in dishes from salad to dessert, the use of fruits, legumes and vegetables of the time. Thus, these books contain lessons in home economics.

Pastas, so fashionable today, have almost no presence in revised recipe books. Vegetables, fruits, legumes, white and red meats, and fish were the dishes on our tables in times past.

Of course, ancestral corn dishes play a key role, but breads and cookies occupy several pages as well. In the main dishes, various cuts of chicken, beef and pork are common. One rich combination is “Pork Chops in Pejibaye Sauce,” that pre-Columbian delicacy that was once served at the inauguration banquet of a president or the visit of foreign authorities, prepared by Costa Rican chef Isabel Campabadal.

Another common ingredient in these recipe books is the viscera. While many noses turn up today at the mere mention of innards, they have a place on the menus in many restaurants today. Thus kidneys, tongue and beef brains as ingredients of gourmet cuisine pass to another more sophisticated stage—but our ancestors provided the origin.

When it comes to pastries, cookies of all kinds delight those who practice family recipes. In the preparation of cakes and pastries, the influx of multiple cultures through immigration is very noticeable, with some very European touches such as nuts, apples and apricots as well as raisins and figs.

Grandma’s homemade jams and mayonnaise have resurfaced in today’s Costa Rica. Some are now on their way to Europe and other parts of the planet in travelers’ suitcases as special gifts for family and friends. These high-quality products are opening doors to new national industries.

Living heritage today

Sandra Flores, a resident of the Otoya and Aranjuez neighborhoods in San José, kept some of the recipes from her school cooking classes received in the Escuela Buenaventura Corrales, or Escuela Metálica, in the late 1950s. She cooked some of them during the upbringing and youth of her children. As her interest in cooking increased, she took private classes to learn both sweet and savory dishes.

At the time of the wedding of her eldest daughter—Zindhy Sotomayor, educator and curriculum specialist at the National Learning Institute (INA), and a resident of Los Sauces, in San Francisco de Dos Ríos—Sandra handed down a recipe book prepared in her own handwriting, with tasty recipes accumulated and prepared by her for years. With this gift, she helped her daughter get started in the secrets of cooking. This is how the culinary heritage is transmitted: today, Zindhy can prepare Christmas cookies and apple pie “Granny Micaela’s Cake”, and other culinary delights from the book.

For her part, business administrator Rebeca Sanabria, now a resident of Santa Ana, very often prepares recipes for stuffed pork chops or the fish Crepes from the recipe book that her mother, Patty Perera, put together during the cooking classes she took for years. As a single woman in her parents’ house, she prepared the family lunch on Sundays for more than 12 people. On special occasions, a friend of her brothers, who today is her husband, was a special guest.

Indeed, “falling in love came through the palate,” says Rafael Sanabria, Patty’s husband of more than 55 years, with a wink. The couple seems to confirm popular beliefs about the power of cooking with love.

“Tita has a gift of making ice cream, desserts and other delicacies that she gives us when we arrive,” say her granddaughters María Pía Verdesia and Mariana Sanabria, young people of the cybernetic age who grew up with fast food. In addition, “she has the gift of color in her crafts, in the colorful and beautiful stitch of the cross stitch, the shadow stitch, the tablecloths and napkins.” All of this, they’ll inherit from the busy grandmother, along with her recipes.

In Cartago, the “Old Metropoli,” educator Flora Cisneros Herrera shows off the cookbook she put together during elementary school classes with Trina Villalobos, a resident of Santo Domingo. The care with which Flora has maintained this treasure takes me back to the beginning in the school kitchen, at the Vitalia Madrigal School, all the students with kitchen caps and aprons with straps, impeccable white with blue trimmings. This notebook by Flora, written first with cap and ink, and then with a fountain pen with blue ink—writing with pencil was prohibited at the time—is a true gem of Costa Rican culinary heritage.

Cooking in times of crisis

Our culinary roots are an intangible cultural heritage. The tradition of recreating family recipes, practicing them, improving them and even marketing them with personalized labels and packaging, gave sustenance and security to a large number of family businesses during health restrictions and job losses due to the pandemic caused by COVID-19.

Grandma’s cookies. Arroz con pollo, improved through family history by incorporating, in addition to the rich smells of the garden, Mediterranean ingredients such as capers, olives, and even raisins. Coconut flan. Tamal asado, biscocho, tamales. figcake, apple pie, jams and other delicacies make my mouth water just from writing their names. All these recipes saved not only those who prepared the food for sale during the pandemic, but also the hundreds of young people who delivered them door to door. These businesses flourished and grew like mushrooms in the winter in Costa Rica and around the world, and they are here to stay.

The entrepreneurship of women and entire families, supported by recipes from grandmothers, aunts, and mothers-in-law, allowed them to provide sustenance and shelter for themselves at the climax of the crisis. Preparing family recipes provided a respite and strengthened the local economies.

Culinary rewards

A cookbook that was begun in the 1940s—when its author, Vera DiNapoli, now 83, was in elementary school—is the oldest I’ve had access to. The wonderful thing about this cookbook is that the author added new volumes over time. As she prepared new dishes, she incorporated procedures, ingredients, and advice from friends and family.

Three volumes will be her heritage for her granddaughters Isabela and Adriana. They will also be passed on to her grandson Daniel, although he’s drawn inspiration from other relatives’ recipes as well: this young entrepreneur, only 20 years old, selected a recipe from his great-grandfather Chicho, an Italian immigrant, to give life to his frozen food business “Pizzas Dinapoli in 8 Minutes.” His pizzas are now distributed throughout the country, along with the secret herb sauces and aromas of his aunt “Cuca.”

The poet Khalil Gibrán wrote, “if you bake bread with indifference, you bake sour bread that only satisfies half of your hunger.” Receiving a cookbook of culinary secrets is like receiving the key to this, the most important cooking technique of all.

All the heirs of Costa Rican cookbooks seem to agree: the best ingredient for a traditional cook is love.