By Greta Moran, Grist, May 07, 2021

–

Our team at El Colectivo 506 is proud to be working with the Solutions Journalism Network on this month’s edition, “Watershed,” focused on reporting by local journalists about their own communities’ experiences with emergencies such as storms and floods. As a part of the Solutions Journalism Exchange, which promotes the republication of outstanding solutions journalism worldwide, we are sharing pieces throughout the month that are related to the Costa Rican emergency response stories in our current edition. To kick us off, we’re sharing this story by Greta Moran, a contributing writer for The Grist, as a part of that media organization’s Sustainable Cities series.

–

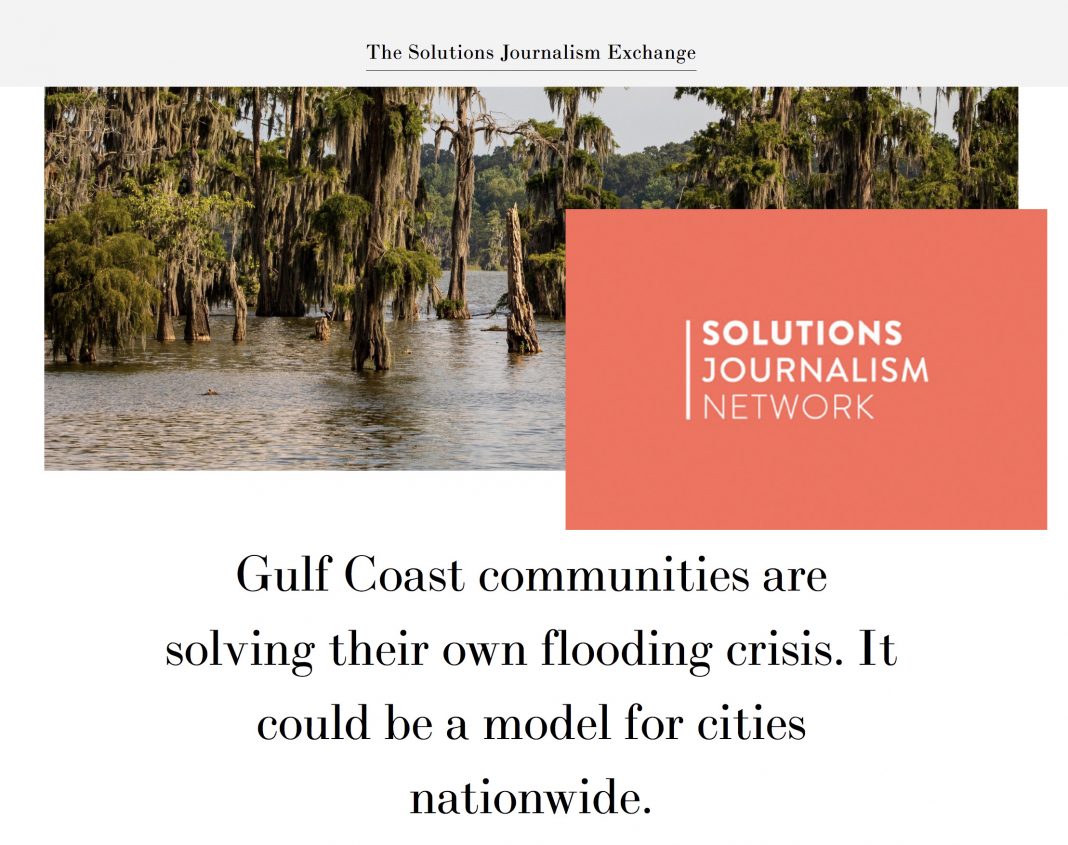

The coastal communities of Louisiana have watched their land steadily disappear for generations. Every hour and a half, a football field’s worth of wetland disintegrates into the Gulf of Mexico or Mississippi River, one of the worst land-loss crises in the world. The state is working to reverse course through the $50 billion Coastal Master Plan, a 50-year blueprint to restructure and restore the coastline. But this ambitious effort can only go so far. The water will engulf more land than hydrologists and engineers could ever restore.

Even with the Coastal Master Plan, vast swaths of the capillary-like coast will be lost in the coming decades and more at risk of flooding by over 16 feet of water. This raises daunting questions: How can the people of coastal Louisiana adapt to inevitable loss? How can they make an informed choice between moving on or staying put on sinking land that has nurtured generations of people, cultures, and livelihoods?

To answer this, Louisiana engaged in a unique decision-making process facilitated by community leaders and directed by thousands of people facing these choices. State officials enlisted the Foundation for Louisiana, a racial and gender justice nonprofit, to create Louisiana’s Strategic Adaptations for Future Environments (LA SAFE). The idea was to give Gulf Coast residents unvarnished information about the scope of the threat and invite them to devise solutions that address their specific needs. “We made the decisions. We decided on the projects,” says Darilyn Turner, a lifelong resident of Plaquemines Parish who directs the Zion Travelers Cooperative Center. “It was something done by the people.”

Those solutions augment the nuts-and-bolts infrastructure projects of the Coastal Master Plan. Many of them, ranging from expanded mental health services to affordable housing designed to withstand floods and storms, are underway. The innovative approach to developing them was based on a simple, yet profound, idea: Trust communities to know what they need, invite them to tell you, and provide the support to make it happen.

Although the effort focused on the rural Gulf Coast, it’s a model that can serve communities of all sizes, from small towns to major metropolitan areas. The LA SAFE process shows how governments at any level can meaningfully integrate frontline communities into climate planning, moving beyond simply asking residents for their perspectives to giving them the authority and resources to decide the best way forward. This differs from most government processes where the viewpoints of a small sample of affected groups are heard, often through public hearings and public comment periods, but not necessarily heeded, let alone adopted.

Changing this conventional dynamic will be essential as the Biden administration, alongside states and cities, commit to addressing climate change and environmental justice. The communities hardest hit by these two crises have long fought for solutions even as they’ve historically been underappreciated, if not ignored, in government processes. The LA SAFE program’s deep level of community engagement offers a new way forward by giving residents a say in decisions that affect them and developing solutions particular to their unique cultural, economic, and environmental needs.

‘You have the ability to control how your future looks’

Louisiana’s steady erosion threatens the existence of many towns. Already, the populations of some parishes (roughly equivalent to counties) are declining. “Folks who reside in those coastal communities are losing their cultural identity and social norms,” says Angela Chalk, a New Orleans resident and founder of the nonprofit Healthy Community Services. “Younger families are moving away.” The decision of whether to stay or leave — assuming they have the resources for that to be a choice — is high on many people’s minds. Then there’s the question of what they need to survive and lead a good, happy life.

To answer those questions, LA SAFE spent most of 2017 hosting 71 meetings that drew nearly 3,000 residents of Jefferson, Lafourche, Plaquemines, St. John the Baptist, Terrebonne, and St. Tammany parishes to discuss their ecological, economic, cultural, and even mental health needs. Everyone spoke frankly about the existential threat land loss poses, something organizers underscored with maps showing how much coastline will be lost under various timeframes, even with the Coastal Master Plan implemented.

“It was the first time that someone in our community came to us and told us that it was not going to be OK,” says Jonathan Foret, a Terrebonne Parish resident and executive director of the South Louisiana Wetlands Discovery Center. Rather than leaving him resigned, the process provided a measure of hope by showing folks they have options, especially if they work together. “You have the ability to control how your future looks,” he says. “If you don’t plan for it, Mother Nature will make those choices.”

LA SAFE made participation as easy as possible. They offered stipends to those who led the meetings, provided childcare, and helped out with transportation. Translators made the information available in Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Spanish. Organizers made a point of holding meetings in the evenings and on weekends so working people could attend, and offered hot meals. To encourage people to speak freely, trusted community leaders acted as table hosts, leading small discussion groups and summarizing the main points for everyone in the room.

“Right off the bat, they made my voice feel valuable,” says Donald Bogen, who lives in Lafourche Parish and is co-director of Bayou Interfaith Shared Community Organizing. “They asked us what we wanted to know.” He especially appreciated how everyone’s comments were written down, because it made him feel people were taking his perspective seriously. Others liked being able to jot their ideas and comments on Post-It notes. “If I didn’t want to speak up, I still had a venue to express my thoughts,” says Ivy Mathieu, a resident of St. John the Baptist Parish.

Even the decision on which ideas to pursue was left to local residents. During LA SAFE’s last meeting, in December 2017, everyone ranked the proposals according to their preferences. Those that scored highest were eventually funded and implemented — perhaps the most direct way of signaling that LA SAFE truly valued the community’s ideas.

Beyond green infrastructure

The adaptation plans that arose from all those meetings reflect the needs of the communities and will help people lead the best lives possible in a region facing great uncertainty.

They include efforts to divert stormwater, like planting native vegetation to help absorb storm runoff and terracing restored marshland. But the plans look beyond infrastructure to other needs. For instance, Lafourche Parish is building affordable housing designed to endure severe storms and frequent flooding. Jefferson Parish opted for a wetlands education center to expand community knowledge of the environmental changes facing the region and engage people in planning for them. Residents of Plaquemines Parish made it clear that they need more substance abuse and mental health services to help residents already dealing with the worst effects of climate change. “We heard over and over again from these communities that people are dealing with mental strain, anxiety, PTSD,” says Liz Russell, the climate justice program director at the Foundation for Louisiana.

Louisiana officials expect to have construction finished on all the projects by the end of 2022. Many are being funded through federal community development block grants, which typically underwrite post-disaster housing, infrastructure, and the like. Using them for climate change adaptation programs represents an expansion of what disaster recovery can look like, especially in a place like coastal Louisiana where the crisis is both acute and ongoing.

Of course, the goal of the LA SAFE program wasn’t just to respond to the crisis — it was also to give residents hope. During each meeting, organizers made a point of asking, “What do you love about your community?” because ultimately, that is what is most worth preserving. Some mentioned being able to subsist off the land. Others cited the uncanny way neighbors show up to help just when you need it. And many of them mentioned the amazing food and music of the region’s Creole, Cajun, and Native American traditions.

When I put this question to Foret, he said, “It is not uncommon to find a bag of oranges on your doorstep or a carton of eggs near your mailbox, because your neighbors share the overabundance of food they may have.” It’s a tradition he hopes to see carry on, even as more land gives way to water. By asking Foret and others like him how best to address the crisis, state officials have made that outcome just a bit more likely.