“And she is doña Loly, the soul of this place,” says Verónica Hernández Zúñiga, as we walk through the gates of the Cocorí Senior Center, Cartago, about 3 km from the center of the canton. It’s Tuesday, around noon. Verónica is in charge of the program for the elderly at the Municipality of Cartago.

Loly, as 80-year-old María Dolores Coto Madriz is known, comes out of the kitchen at the back of the building wearing her apron, hairnet and mask to welcome us to the center she founded and where she has volunteered for more than 20 years. The building, with large windows and about seven long tables where twenty elderly people carry out multiple activities, is the most recent member of this organization.

“I started with eight people. We supported ourselves with the small amount that each one could contribute,” recalls Loly. “The group grew, we reached 20 people, and I had nowhere to put them.”

She managed to speak with the mayor, and on December 23rd, 2012, they inaugurated the building for the use of the Cocorí Association of Agua Caliente de Cartago for the Care of the Elderly.

The center is more than a building where adults can spend the day and have lunch. Loly says there they can safely share their problems and joys; they can feel appreciated and supported.

“There is something that I have seen a lot in families: such a lack of love [towards the elderly],” says Loly. “That motivated me to start.”

The canton of Cartago has a high population of older adults. According to Verónica, the municipality has included care for this population among its policies and priorities since 2014. That’s how, in 2015, the program that she coordinates was created. Verónica is in charge of supervision and collaborative work with 17 day centers such as the one in Cocorí. Before the pandemic, those 17 centers served more than 200 people per day. During the months when it was closed down because of health restrictions, all older adults who are part of the centers received a monthly food subsidy. In December 2021, six of the centers were back in operation, serving more than 130 people.

But as Verónica explains, the work of the municipality goes beyond supporting those centers. The municipality has invested in improving sidewalks and road crossings; it has trained bus drivers from the canton’s most important routes. And it continues to promote activities for the training, education and recreation of both older adults and caregivers.

All these efforts are aimed not only at complying with municipal policy, but also at fulfilling the commitments Cartago took on when it became a member city of the Global Network of Age-Friendly Cities and Communities of the World Health Organization (WHO).

What is an age-friendly city?

According to the WHO, 792 cities worldwide are part of the Global Network of Age-Friendly Cities and Communities. Since 2019, Costa Rica has added 19 cities to that list. Those communities are Cartago, El Guarco, Belén, Heredia, Flores, Curridabat, Montes de Oca, Tibás, Mora, Dota, Coronado, Santa Ana, Grecia, Zarcero, San Carlos, Alajuela, Orotina, Esparza and Tilarán.

But what does it mean to be an age-friendly city or community?

The WHO explains it as “a place that adapts its services and physical structures to be more inclusive and receptive to the needs of its population to improve their quality of life as they age. A friendly city encourages healthy aging by optimizing resources to improve the health, safety, and inclusion of older people in the community.”

Under this premise, the cities that decide to be part of the network must work in eight thematic areas: transportation, housing, social participation, respect and social inclusion, civic participation and employment, communication and information, community and health services, and outdoor spaces and buildings.

The ultimate goal is for the city to allow older people to more easily navigate public and private spaces. Those improvements have an impact on the entire community, no matter its age.

“A city that is friendly to older adults is a city that is friendly to all people,” says Andrea Terán, who runs the Senior Program at the Yamuni Tabush Foundation, an organization that has been working since 2019 to support cities that make up part of the Network in Costa Rica.

How are Costa Rican cities becoming age-friendly?

Flor Murillo, an official from the Ministry of Health who coordinates the Technical Commission for the Approach to Healthy Aging (CONAES, using the Spanish acronym), explains that the work carried out in Costa Rica with municipalities and communities that seek to be friendlier to the elderly is a complex process. It has also suffered slowdowns due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since 2019, when the first 12 municipalities formalized their participation in the Network, local governments have been able to receive training from a special commission that includes the Yamuni Tabush Foundation, the National Association of Mayors and Municipalities (ANAI), the Municipal Development and Advisory Institute (IFAM) and the Ministry of Health.

“We provide technical support to the municipalities so they can develop the initiative,” explains Flor. “We have a continuous training process for which international experts are brought from other cities in the world that are already [friendly cities] so that in Costa Rica we can learn from what is being done. They are also given planning tools, group formation tools, et cetera, so that there is greater social participation by older citizens.”

Flor adds that in 2021 they trained 120 participants, and they will resume in February 2022.

The Network’s eight axes of action require improvements in both the infrastructure of cities and the social processes that incorporate the elderly. This work of planning and inclusion takes time and resources that not all municipalities have.

“It has to do with the human development index. These are among the highest,” says Flor, referring to the 19 municipalities that have already expressed their commitment to becoming age-friendly. “So [these municipalities] don’t have to solve problems like roads or other things, and they can spend more time on social programs.

“We already have many municipalities that have advanced in important strategies, such as Cartago, Montes de Oca, Curridabat, Tibás, Heredia, Grecia and Belén,” she adds.

In the case of Cartago, Verónica explains that the advances of the municipality in areas such as infrastructure are mainly seen in the work on sidewalks and street intersections in the city center. In terms of social participation, respect and social inclusion, and civic participation and employment, the work carried out in day centers for the elderly has been vital. The municipality has also provided training on information and communication technologies in partnership with public universities, and created virtual spaces to promote the participation and interaction senior citizens.

Regarding transportation, the municipality conducts awareness training with bus drivers on two routes within the canton, Agua Caliente and Guadalupe, which has not only promoted better treatment by officials towards users, but also generated community.

“Get to know people not as users of a service, but as people,” says Veronica about the awareness processes where drivers coexist with older adults in the community.

Verónica notes that some other areas of action are particularly complex, such as housing: “We cannot come and build housing, but the issue of accessibility is included in the urban development plan.”

The other municipalities that have made progress are Montes de Oca, Curridabat and Tibás. Since 2019 they have received technical and financial support from the Yamuni Tabush Foundation.

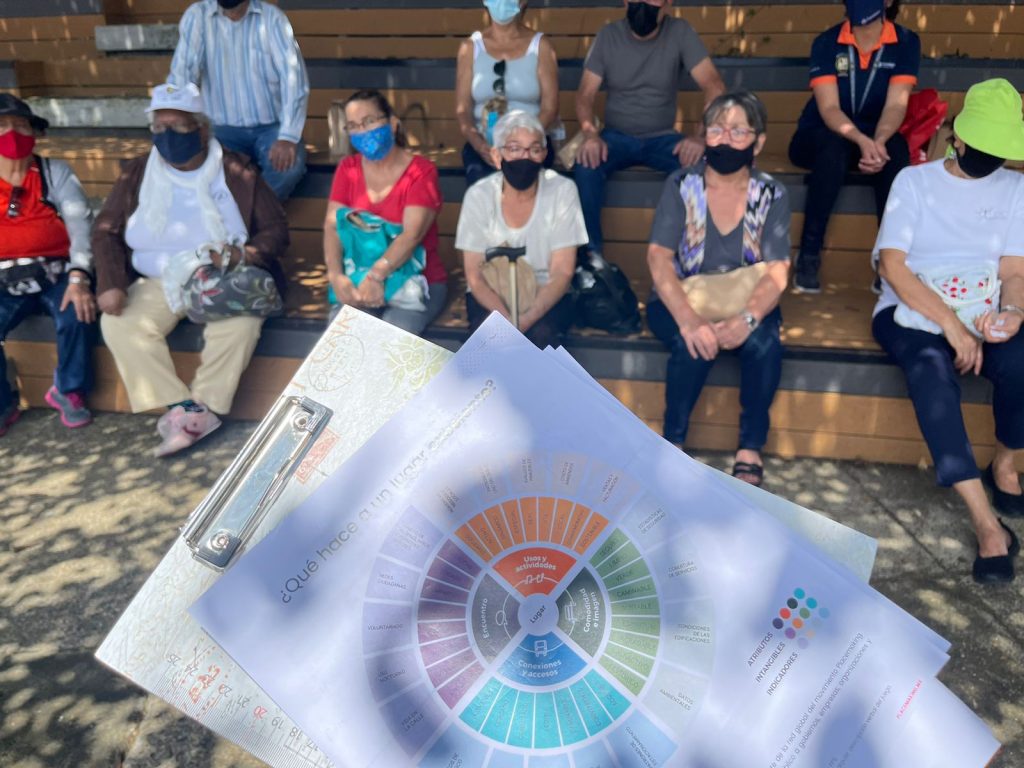

This process began with the generation of profiles and cantonal diagnoses that reflected what the cities have and what they lack. Above all, they allowed municipalities to hear from the older adults of each community about needs that were not being addressed.

“The pain points of older adults when using the city are many and similar in the three cantons, which means that there are latent unresolved needs that are almost universal for the older population,” says Andrea, from the Fundación Yamuni Tabush. “The area where people had catharsis and we had to say ‘now!’ was the area of accessibility and transportation.” She adds that Costa Rican legislation obliges property owners to maintain their sidewalks, which translates into irregular and dangerous topographies for all people, elderly or not.

“That means unwanted loneliness,” says Andrea, arguing that older people may start to see streets and sidewalks as a risk and decide not to go out. “Unwanted loneliness is known to be an older person’s biggest enemy.”

Based on the assessments, the municipalities developed action plans with specific activities that have been supported and financed by the foundation. Each municipality received a donation of $43,300 for this purposes.

Montes de Oca and Curridabat decided to invest resources in walkability circuits, to generate accessible urban corridors that also connect points of interest for older adults. Tibás, known as the “city of parks,” worked on improving three public spaces to make them more inclusive.

Sandra Vega, social and cultural promoter of the Municipality of Montes de Oca, is in charge of her municipality’s project and explains that the route they are working on seeks to connect el Cristo de Sabanilla with the Plaza Máximo Fernández, known as Plaza Roosevelt. The first stage of the project took advantage of sidewalk repair work that the municipality has carried out on 1.7 km between the Pituca cookie factory and Plaza Máximo Fernández. With the foundation’s donation, 86 bushes and plants have been planted, and street furniture will also be added (34 benches and chairs, eight metal tables with chess boards, and two parking spaces for bicycles). The choice of rest spaces and planting locations was carried out in consultation with senior citizens in the community, and with the technical criteria of municipal employees.

Lessons learned from advancing towards friendly cities

“The beauty of this process is that it has been truly participatory with older adults,” says Sandra about the experience in Montes de Oca. According to her, all decisions were made after consulting approximately 175 older people. This approach allowed the municipality to build a “database of coordinators of the canton, which is essential for any coordination, so we could count on their support in any action we carry out.”

The processes in the three municipalities supported by the Yamuni Tabush Foundation were financed in three different ways. For Andrea this resulted in “great learning” for future municipalities that need to achieve these cantonal diagnoses. In Montes de Oca, the Foundation donated the work of the Center for Urban Sustainability. Curridabat had the capacity to do it internally. Tibás had budget approval to develop the municipal aging policy, and the research for that was used to make the diagnosis.

The collaborative processes established with national organizations such as Yamuni Tabush, and international organizations such as the Placemaking Foundation in Mexico, have made it possible to bring accessible innovation to urban transformation processes. These alliances also supported municipalities so that they could not only see the importance of becoming age-friendly cities, but also find the process less overwhelming.

The challenges of being a friendly city in Costa Rica

“In terms of friendliness, we are not at 100%. We still have a long way to go,” says Verónica about Cartago’s achievements. “The canton of Cartago is very large. Depending on where we are, the older adult will say if it is friendly or not.”

Verónica explains that of the 11 districts that make up the canton, four are rural and seven are urban. As a result, each district’s challenges in age-friendliness are very different.

Montes de Oca, like Cartago, is a canton with great disparities within its own territory. Although it already has a walkability plan and several parks, they are concentrated in the main district.

“I find it very sad that in an area as beautiful as this one, 90% of the population that lives in a slightly lower socioeconomic condition can only walk around in one triangle. There are no free spaces,” says Ingrid Ugalde Esquivel, 56, who has been a resident of the San Rafael de Montes de Oca district since 2016. From her home, she watches her neighbors walk their pets in a grassy area, the only nearby outdoor venue that doesn’t charge admission.

Ingrid moved to Montes de Oca when she retired after living in the center of the canton of Curridabat for 29 years.

“I came here and I was scared,” she says. “Curridabat is already more friendly for walking. I arrived here in San Rafael and it was impossible.”

Ingrid volunteers to coordinate the Cáliz de Amistad senior group at her Catholic Church, which was part of the consultative processes in the canton.

“The most important limitations are budgetary ones”, says Sandra about her experience as a employee in Montes de Oca. “While we have very good ideas and nice projects, we would like to have much more resources to be able to take into account all the projects and integrate them.”

For Andrea, this challenge can be addressed in a different way.

“If accessible corridors are created and people know that these routes exist, the challenge is to make it easier for them to get to this route. From there they can exercise and run their errands in a place that is not threatening or exclusive,” she says.

But she also alludes to another challenge: cities that want to be friendly to the elderly face more than geographic diversity.

“It is a very diverse population. We cannot think that their destiny is to do crafts in a center,” says Andrea. “They want to learn languages and history, volunteer, continue participating, make art.”

Active inclusion

On the Tuesday of my visit to the Cocorí Senior Adult Center, Loly started cooking early in the morning to prepare lunch and bake bread for afternoon coffee. That day, everyone, including the visitors, had fish in tomato sauce, rice, beans, fried yucca and tamarind juice for lunch.

While she works hard in the kitchen, water splashes all over the pool in the sports center while laughter, shouts and choruses of songs resound to the rhythm of Costa Rican swing criollo. More than 40 older adults participate in an Aqua Zumba organized by the municipality’s Cantonal Sports and Recreation Committee. The class led with great energy by an older adult.

A little later, in Cocorí, three women practice an embroidery technique, while other people watch a soap opera on a large television that dominates the quiet room. To the left, a man is consumed in a sea of tiny puzzle pieces, and a few feet away from him another man applies an electric massager to his knees and shoulders. Outside, Carlos Enrique Araya Mora, 79, takes care of the vegetable garden, a job he does seven days a week, and which he did all his life as a farmer.

“My joy is to come to sow and take care of the plants,” says Carlos. “If I had more land, I would plant more, to help the center and other people.”

Everyone is doing what they like.

This February 14, doña Loly will be 81 years old. As she has done for almost two decades, she hopes to camouflage her celebration within a Saint Valentine’s day party.

What is her advice for healthy aging?

“We have to think that we were born to serve, and to give love to others.”