When an emergency occurs in a community, the relevant government entities activate their protocols. But what happens when a community like Monte Verde is hit by an event such as Tropical Storm Nate, and all communication with the outside world is lost—not to mention access to electricity, telecommunications and potable water, further complicated by road closures? How can a town handle a massive emergency without any guidance from experts in the field, and also without any material resources?

“After Tropical Storm Nate in 2017, the district was isolated for three days due to the collapse of roads that connect the sector with the outside,” says Margarita Salazar, member of the Commission. Municipal Emergency Department of Monte Verde. “We remember having felt as if the community had become an island, or even worse, ‘The Independent Republic of Monte Verde,’ a phrase that we now use as a bitter joke to remember those hard days. Of course, it was clear that we had to take charge of the situation and act alone to emerge from adversity.”

Monte Verde could not sit back and wait for the government or other institutions to resolve the situation. With the limited information they had at the time, district leaders knew that they had to act because this emergency was not only local: other sectors of the country were being affected, and there was no way of knowing how long it would take for Monte Verde to receive any help. That’s when a feeling of collaboration began, with public and private institutions, as well as many individuals, making themselves available to the Municipal Emergency Committee of Monte Verde to work together for the common good. Their goal? To enable a community devastated by the onslaught of nature to normality as soon as possible.

How was this volunteer response achieved in Monte Verde? And, almost five years later, what has the community done to turn that spontaneous response into stronger and more replicable structures?

A crisis in the cloud forest

Monte Verde is district number 9 in the province of Puntarenas. It is well known for its nature, protected areas, tourist attractions and above all for its cloud forest—as well its history, shaped by the arrival of Quakers to the area in the 50s. Since its inception, this small town has worked to be as self-sufficient as possible. For this reason, in 2001 it was declared a district (registering the name of the district and geographically as Monte Verde, two words. As a tourist destination, it is widely known by the name of one of the district’s communities, Monteverde).

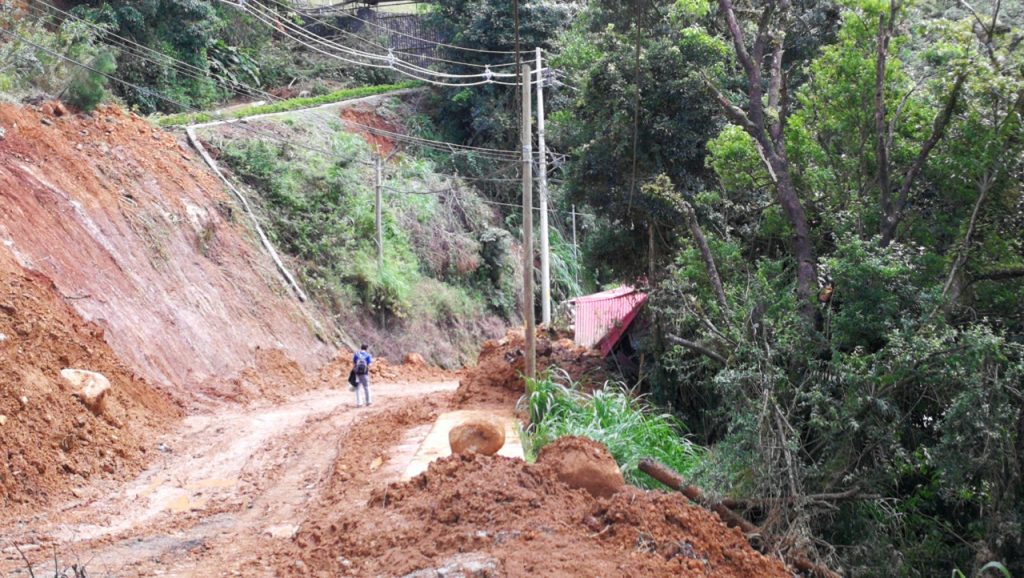

From October 4-6, 2017, Costa Rica was affected by Tropical Storm Nate, which would hit the United States a few days later as Hurricane Nate. Monte Verde was one of the areas that suffered the most from the impact. Many roads, houses and even protected areas were affected by heavy rains and multiple landslides. According to the studies and measurements at the time carried out by the el Institute Monteverde (MVI), una organización educativa sin fines de lucro fundada en 1986 en Monte Verde, (MVI), a nonprofit educational organization founded in 1986 in Monte Verde, the storm dropped 17% of Monte Verde’s usual annual rainfall in just two days of constant downpours. To further complicate matters, by the time Nate hit Monte Verde, it had already been raining in the district for more than two weeks in a row.

The storm left the community isolated by landslides on access roads and district roads; without electricity; without potable water; and without telecommunications services. As the rain continued to fall on already saturated soils, the flooded slopes began to give way. Streams overflowed, sweeping roads and bridges such as the Buen Amigo bridge in San Luis. The residents of two of the district’s communities, Monteverde and San Luis, were isolated as landslides fell on different streets and highways.

“The most serious thing about the whole situation was the lack of communication with the outside world, not knowing what was happening in other parts of the country, but mainly that the rest of the country and the government were unaware of our situation in the district,” says Margarita. “However, we had to start coordinating and working to move our community forward with our own means.”

Fortunately, no one was injured during the storm, thanks in large part to the excellent coordination and efforts of the Monte Verde Municipal Emergency Commission (CME). Neighbors gathered to help each other and hear the latest updates from the emergency commission. Services were restored and roads opened in what seemed like record time, although long-term road repairs took much longer.

“For this emergency, there was the collaboration of many neighbors who contributed their labor to enable access and essential services in a short time,” says Yeudy Ramírez, current Mayor of the Monte Verde district. After a year Monte Verde had largely recovered, while many communities in the country were still struggling..

So Monte Verde authorities and community leaders decided to build on what they had learned during Nate, and develop improvements that would allow them to harness their volunteer force even better in future emergencies.

Studying the human response

The first thing leaders did in Monte Verde was simple: study what had happened during those days of crisis. What happened during the emergency ranged from tragic to inspiring.

According to Randy Chinchilla, one of the leaders of this study carried out by the Monteverde Institute, four aspects were examined: how people adapted, what they did to recover, how they prepared for this event, and how they plan for the future. In other words, the team at the institute studied community reaction and resilience.

The study concluded that Nate created a new reality, common after trauma, known as a “third estate,” a term that is credited to Nalini Nadkarni. According to the Institute, the first concern of those affected was the well-being of other people in the community. Neighbors looked to each other asking, Are you okay? You have food? Water? They shared resources, worked to communicate needs and concerns, collaborated to clear paths and meet diverse needs. There was already a strong sense of community, but most of those surveyed felt that the storm had increased this tight-knit feeling, motivating them to focus on the needs of others and to become conscientious volunteers.

Margarita, the Municipal Emergency Committee member, explains that after analyzing these ideas and other lessons left behind by Nate, the committee set the goal of building a more robust committee and improving preparedness by creating work groups, or mesas de trabajo. These function as sub-committees, each with a specific task; this way, no one group has too many functions, and there’s no redundancy. For example, the Social Aid Sub-Committee, in charge of socioeconomic issues related to the care of families and other groups, is made up of at least one member of the Municipal Committee, other volunteers related to the issue, and representatives of public and private institutions, NGOs, and residents.

In addition to the Social Aid Sub-Committee, there are groups for Preparation and Response, Security, Basic Services, Health, Food Safety, and Logistics. The latter is one of the first to be activated in an emergency, since it is made up of the Coordinator of the Emergency Committee (this role is filled by the district mayor, or intendente); the Municipal Engineering Department; a representative of the Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve, which has ample experience in communications and risk situations in the mountains; and other residents with extensive experience in emergencies in the area. During an emergency, this sub-committee begins to activate its protocols. From there, the other teams begin taking action in their assigned areas.

The Basic Services Sub-Committee is made up of personnel from the Costa Rican Electricity Institute (ICE) for electricity and telecommunications services, Municipal Planning for garbage collection, the Aqueducts of Santa Elena, San Luis and Monte Verde, and representatives from the district’s two gas stations. In case of emergency, this group works to restore necessary services as soon as possible to minimize the impact of a disaster.

Finally, the Health Sub-Committee brings together Costa Rican Social Security (Caja), the Ministry of Health, the Red Cross, the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock (MAG), and the National Animal Health Service (SENASA). The group is in charge of ensuring the health of victims, volunteers, the general population, and animals during and after the accident.

Maria Isabel González Corrales, the Vice Mayor of the Monte Verde District Municipal Council and Deputy Coordinator, says that these sub-committees have allowed leaders not only to organize the volunteers who participate, but also to facilitate public-private coordination.

During Nate, several examples of this coordination sprang up. One of them is the Monteverde Institute, which became an information center and a place to supply water to neighbors and volunteers, and prepare meals. The Municipal Emergency Commission subsequently requested that the Institute become an official place of shelter in case of emergencies; the Institute accepted this responsibility. This means that in the future, emergency supplies will be provided to the Institute (beds, water, medicines, and so forth), so that it can serve as a refuge.

After what happened in Nate, leaders saw that everyone who participated was willing to work, but that communication and organization were sometimes complicated. Today, all these new sub-committees have a WhatsApp chat including all members of the group, which allows them to stay informed about emergency situations and coordinate when to activate each sub-committee’s protocols. What’s more, in case of telecommunications failure, each group has two defined meeting points established where they will meet to coordinate their work: point A, the primary meeting point, and a point B in case structural damage makes it difficult to access the first point).

Each sub-committee maintains a list of potential volunteers who are willing to work and collaborate in whatever is necessary. When the lists of volunteers were compiled, each volunteer’s abilities and interests were matched with the needs of each sub-committee. Among these volunteers are the team that helps with cooking for volunteers or in shelters, and people willing to work in the field, those who pack supplies to deliver to families, among others.

“Without this workforce, it would be impossible to carry out all the tasks that are necessary, all at the same time,” says Jennifer Ugalde, secretary of the Monte Verde CME.

What differentiates Monte Verde from communities?

“Monte Verde is characterized by the spirit of solidarity of its inhabitants. These are people who do not wait for a solution, but are always proactive and seek how to move forward,” says Yeudy Ramírez Brenes, Municipal Mayor and Coordinator of the Emergency Committee. “The community thought about the impact that volunteering had in this situation, how it had helped address needs so quickly, and how we could make even better use of this valuable resource.”

Improving the flow of resources

Monte Verde’s experience of Nate also demonstrated the need for a centralized fund that could redirect donations in a transparent and timely manner. Sometimes government or NGO support became available, but it took a long time to be executed, especially in the case of public funds.

This process accelerated when the COVID-19 pandemic hit Monte Verde, where it caused true economic and humanitarian disaster in the district’s tourism-dependent communities. Because of the lessons left by Nate, it took only days for Monte Verde to react and set up the 2020 Emergency Fund in collaboration with the Monteverde Community Fund, or MCF, which partnered with the Municipal Emergency Commission and the Liaison Commission to provide existing capital and offer fundraising services. (The Liaison Commission is made up of people from the community to support the Municipal Emergency Commission.)

Starting on March 20, 2020, MCF platforms have been used to collect donations on a local, national, and international level. In addition, alliances have been created between community entrepreneurs who contribute $1 to the fund for each visitor they receive. This provides the Community Fund with resources that it can redirect to the local Emergency Commission when necessary.

One of the participating entrepreneurs is Rafael Eduardo Arguedas, from Cabañas los Pinos. Don Rafael and four more hotel owners created a Solidarity Alliance at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Each hotel contributes $1 per night for each guest who stays in its facilities. Of this amount collected, 50% is delivered each semester to the Monteverde Institute, and the other 50% to the Community Fund. These funds have been used in multiple ways to address the damages caused by the COVID emergency and other events that occurred after Nate.

The creation of the centralized fund with the Monteverde Community Fund has allowed the Commission to invest in education and information in order to prevent contagion by Covid-19, adapt family expenses to the new reality, provide legal advice and financial support for families and businesses, offer psychological support for the population, and create a Food Bank for low-income families. The Social Aid Sub-Committee and Monte Verde Municipal Council have been granted space to receive, sort, and distribute food donations.

These funds also allowed the Commission to gather unemployment data during the pandemic and identify affected households. As a result of this work, the Liaison Commission, which led this effort with the Statistics and Census Institute, created an online survey that reached more than 1,400 people and allowed organizers to identify the families at greatest risk. This action enables the Emergency Commission to organize and prioritize donations of food and other resources more effectively.

Finally, the funds that have been raised allowed the Commission to achieve, propose and develop a local food production plan—not only for eventual shortages, but also to generate solidarity, improve nutrition, keep money within the community through local purchases, and document the experience. Funds have also been used to generate and share audiovisual documentation in local digital media and chat groups, shining a light through local online media on Monte Verde’s community response. This material has proven useful in communicating local experiences both locally and with other communities.

Improvements for the future

The creation of the Emergency Fund is just one example of how lessons learned through Tropical Storm Nate have helped the community organize during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Following Nate, Monte Verde has not experienced any climate events of that magnitude, but the pandemic provided a different kind of challenge—something for which again no one was prepared.

“Monte Verde has been characterized by undertaking its struggles without waiting for everything to come to it, without waiting for government institutions or things that fall from the sky through sheer luck. On the contrary, they have worked hard. During the most difficult moments, they have hit it out of the park,” says Yeudy Ramírez Brenes, the Municipal Mayor. “In recent years, the District has faced two difficult events with a massive impact: Nate, and the Covid-19 pandemic… With Nate, it was impressive to see how a community came together to solve problems… that is the spirit of Monte Verde.”

“Now with the COVID-19 emergency, the same thing is happening. This is one of the few districts that are still making deliveries of basic food packages delivered by the CMEs in an orderly and transparent way. All this work is not done by the Committee alone. This is not done by only five people. This is achieved through many hands that collaborate without receiving anything in return. That’s the essence that characterizes us.”

This time, with more organized volunteering systems than during Nate, institutions and individuals united to plan ways to support tourism-dependent communities where most people’s income fell to zero. The impact of the improvements made after Nate were evident on several levels—and through its more robust and structured volunteer systems, the community also identified new challenges and areas for improvement.

Jennifer Ugalde, a member of the Committee, indicates that there are still many things left to learn. An example is finding new ways to care for and protect volunteers, since with the new COVID-19 emergency, volunteers are highly exposed and vulnerable to contagion. During the pandemic, Monte Verde had to optimize not only economic but also human resources. Unlike other crises, volunteer work has not been a matter of 48 or 72 hours, but of more than a year: as the months ground on, volunteers became worn out, which has forced them to reinvent themselves on the fly. The community learned that volunteers must be rotated to avoid burnout, but it is difficult to do that without affecting the continuity of established sequences and biosafety protocols.

Finally, Jennifer indicates that the leaders of the Monte Verde efforts are trying to attract more young people to do this work, because most of the volunteers are above 35.

She says that the members of the Committee and Sub-Committees are working continuously to address these challenges. The Committee is working on developing a strategy or campaign to inform the population about how to volunteer, and organizing campaigns with officials of the Caja and the Ministry of Health to train volunteers in COVID-19 protocols. Members are also reviewing and discussing experiences during COVID-19 to identify possible solutions to other challenges for the future.

“We have many hopes for the future of the Emergency Committee and the local government,” says Yeudy. “We dream of a Monte Verde that is reborn and transformed despite adversity—that does not regret emergencies, but rather learns from them to be better every day, and to have greater hope for its citizens, residents and visitors. There is no separation. nor any distinction: here, we are all one team. We also dream of seeing the district with streets in the best condition, recreation areas for better mental health, and always seeing each other as brothers and sisters. This is what we are.”