Read the first part of the series here: “A harvest turned upside down.”

Máximo Palacios, 39, is a lean, quiet man with a slow smile. He doesn’t often show great emotion, but he does betray some when he is asked about the home he leaves behind in Panama each year to pick coffee in Costa Rica. “Muy bonito allí,” he says, “very nice.” He looks slightly wistful as he describes the wooden house where he lives with his family, high in the mountains of Bocas del Toro province, Panama.

Three kinds of monkeys frolic in the trees back home, he tells us. There are tepezcuintle, chancho de monte, and wild turkeys. His family grows its own food, like most people in Panama’s sprawling indigenous comarca, where paid work is very hard to come by. They have no electricity, but paid $80 for a solar panel that provides enough energy for light and to recharge their phones. His mother lives a few hours’ walk away, and his family will often spend the day walking through the forest to visit her.

They had a much longer walk ahead of them on October 20th, 2020, when they rose at 5 am and left their house behind—in the care of Máximo’s only son, 17—to start their annual journey to Costa Rica. Máximo, his wife Élida, and their four daughters – Ilda, who is 20, and teenagers Ofelia, Yorlinda and Liliana—walked for 12 hours to reach a friend’s house where they could sleep for a few hours. At 2 am on the following day, October 21st, they rose again and walked three additional hours to a place “where cars pass.” There, they were able to catch a six o’clock bus to Bugaba, the Panamanian town where they needed to begin their immigration paperwork and medical review in order to continue on to the Panamanian border.

At 3 pm that afternoon, nearly 34 hours after stepping across their threshold in Bocas del Toro, the Palacios family finally reached the Panamanian-Costa Rican border station at Río Sereno. They stepped off the bus from Bugaba into a light rain under the relieved gaze of Minor Jiménez, the farmer who had traveled from Los Santos to receive them. He expected a total of 25 workers—but to his surprise, he found that only six, Máximo’s family, had actually made the trip. Well under the number he’d hoped to bring back to Los Santos that day to start picking the red fruits from among the green; well under the 40 he’s calculated he needs to scrape by at the height of the season; further still under the 60 coffee pickers he might have in a regular year. Just six today, tired from their long journey, still so far from the end of it.

All over the border, similar dramas take place, and WhatsApp messages fire fast and furious between Costa Rica and Panama. One farmer blurts out: “If they don’t come, I might as well cut down all my coffee and start farming cattle.” A female farmer learns that the workers she’d expected couldn’t make it, but other indigenous migrants have shown up without a farm to go to. If they don’t get a farmer to sign on, they won’t be able to cross. Moving fast, she gets the names of the new arrivals, puts them on her official forms, and pushes the paperwork through to receive the workers and take them to her farm. Around her, bus drivers carrying power of attorney from the farmers they represent pull off similar swaps, hour after hour, day after day.

Six instead of 25 is a blow for Minor, but still, he picks up his phone and calls his father to tell him Máximo has arrived at the border station: “Gracias a Dios.” Why so much relief over one family? It’s because Máximo has been working at Minor’s farm for eight years, but also because he’s a hub of sorts. Once he arrives in Los Santos, he’ll be the point of contact who will coordinate the arrival of four more family members, then another 15, then another 12, until Minor’s peak harvest payroll is complete. While six workers are nowhere near enough for even this early stage, Minor knows that when Máximo’s steps off that bus at the border, his farm has moved one big step away from a lost harvest.

However, the Palacios family isn’t done yet. Their journey through the border station will take another four hours. And there will be more surprises beyond that.

The waiting game

There is no wall or even a clear border demarcation here at what has been called the most peaceful border in the world, a descriptor earned when first Costa Rica and then, less notoriously, Panama, abolished their armies. An assortment of single-story concrete government buildings make up each country’s contribution to a border station that sits on the side of a softly curving hill, with stores—heavy on work clothes and basic food supplies—lining the road in the center that slopes down into the small town of San Marcos.

At first glance, the border station is a confusing assortment of lines and waiting rooms and functionaries who come and go. When you learn where to look, however, all of these new alliances are on display. An Immigration official working unpaid overtime to try to get people through before the border closes through the night so they don’t have to sleep in the open. Bus drivers looking out for the workers they’ve been assigned to escort to their farms, and guiding them as best they can through the process that will get them onto their bus. Workers from the nonprofit Hands for Health who hand out coffee, juice boxes, and cookies to migrants who watch their next meal recede into the distance every time a new set of paperwork is placed before them. The food was sent to the border by the Municipal Emergency Commission after José Pablo Vindas, an Immigration Police officer, asked for supplies after noticing the hunger being experienced by workers who were waiting in line.

Perhaps no one runs interference more visibly at this border than Deysi Jiménez, hired by the International Organization for Migration (OIM) as a Cultural Advisor. A Ngöbe woman born and raised on the Costa Rican side of what was once a single territory, she is fluent in Spanish. Wearing the traditional dress of Ngöbe women—comfortable and loose, in a single bright color adorned with geometric patterns—she translates the rules and instructions for non-Spanish-speakers and generally tries to make the process more intelligible for those who are experiencing it for the first time.

This year, that means everyone. Even seasoned migrants like Máximo are at a loss when confronted with this new sea of processes. He will later explain to us that he first came to Costa Rica at the age of 13 or 14 with his father. They often came over the border without documents, but, he says, things have gotten stricter; for years, he’s come through this border station, complying with all requirements. But this year is beyond anything he’s ever seen.

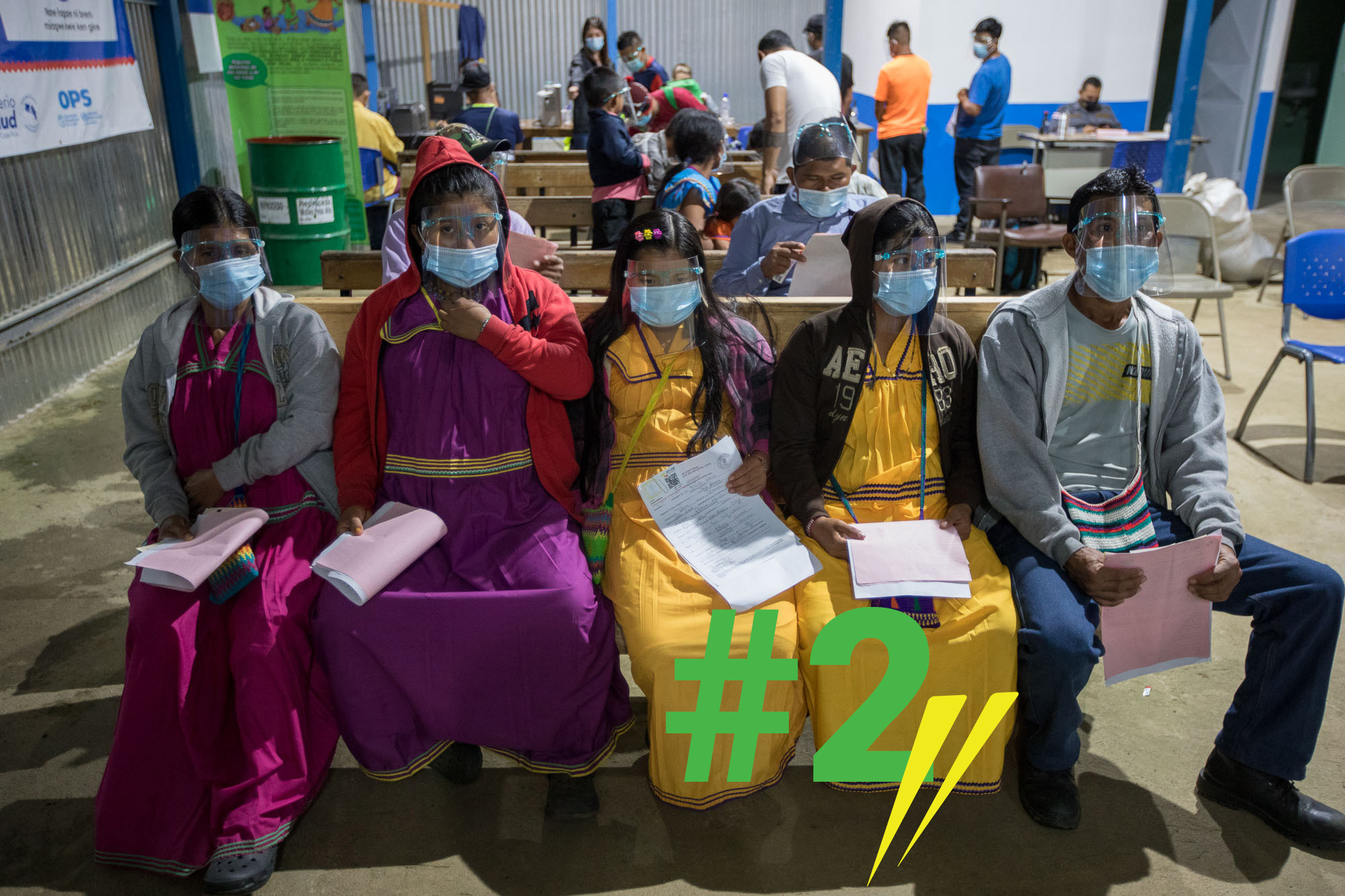

Once workers have received a small class in how to wash their hands properly, they file quietly—masked and wearing plastic face shields to boot—into a roofed space of just 15 x 12 meters where they will spend the next several hours. There, four different government entities will take down each migrant’s information. Separately. Name, contacts, background, health data, the name of the farmer who is waiting for that worker.

For a multilingual population with varied literacy skills—Cultural Advisors such as Deysi help those who cannot write or understand Spanish, and those migrants sign their documents with a thumbprint—it is a long, laborious process. (Asked why it wasn’t possible for the entities to integrate their data and, say, take migrants’ info just once and then replicate it in their systems, Immigration Sub-Director Daguer Hernández explains that there simply wasn’t time, especially since both Immigration and the health-care system face strict confidentiality and security requirements in handling their data.) On the day that Máximo moved through this system, he spent nearly four hours between the Panamanian side and this space.

The room is almost silent, except for the murmuring of officials. The migrants wait patiently, even the children. Even when they must be hungry, like Edgar, 10. He has been traveling for three days and two nights; his dad, Fidel, his mother, Valeria, and his sister, Cándida, will all pick coffee at don Nelson Mejía’s farm near the border. On each night of their journey, the Sánchez Nieto family has slept in the street; last night, they had to sleep here in Río Sereno because they couldn’t get their immigration paperwork done before the offices closed for the day. None of them complains, sighs, or even seems to fidget much. A mother from another family reacts with similar stoicism when her baby soils herself. With nowhere else visible where she can take care of the problem, she washes her off in the hand-washing station, then continues waiting quietly.

There is actually more noise in this room on a later day, when the border is closed because of the lingering effects of Hurricane Eta on the region. Panamanian authorities are eager to discourage their citizens from attempting to migrate given the dangers posed by swollen rivers and other threats. On that day, Deysi’s dress is bright pink, with green adornments. We find her speaking in rapid Ngäbere to a group of migrants who are clearly frustrated (and whose presence here, on the Costa Rican side, shows the porous nature of this border, as well as the need migrants feel to comply with entry requirements so they can work legally). While they initially express reticence about the idea of being interviewed, they are ushered inside the space that is normally filled with waiting migrants and sit down on the empty benches, heads bowed, accepting foil packets of cookies they are offered by Deysi and by Yandellín Sánchez, a project coordinator for Hands for Health.

When one man, clearly the spokesman—wearing a black hat with a bucking bronco and the word “Cowboy”—is asked for his name, he explodes instead with a torrent of speech. He says that his group of 17 relatives has been waiting here at the border for 10 days after a horrific journey from their home in the comarca. During the trip, two of his children died when they were washed away by a river swollen by the rains from Hurricane Eta—precisely the kind of disaster Panamanian authorities had been warning about. He relates the news matter-of-factly, but his anger is on full display.

Monica Quesada Cordero/El Colectivo 506/National Geographic Society Covid-19 Emergency Fund

“There are more than 500 people waiting in Bugaba,” he says, referring to the Panamanian town where migrants must first get their carnet binacional. “There are 400 waiting in Volcán. There are more than 1,000 waiting in Sereno,” on the Panamanian side of this border station.

He finally says his name: Enrique. He is 38. His brother-in-law, 37, Daniel Morales, says that despite the pain of the trip, the Costa Rican coffee industry is worth returning to. “In Panama, the government treats us like animals,” he says, repeating a common refrain of migrants we interviewed: that the conditions for coffee workers in Costa Rica are so much better than they are in Panama, that it’s worth the trip.

“More than anything, you feel sorry for the children,” says Deysi afterwards, sitting outside. She is 36 and has four children herself, the youngest just 18 months old. The eldest child goes to night school with Deysi, who is working towards a high-school diploma after entering school for the first time at the age of 19. She proudly explains that she received her sixth-grade diploma after just one year of study, her first time ever using Spanish in a formal setting.

Monica Quesada Cordero/El Colectivo 506/National Geographic Society Covid-19 Emergency Fund

Her resumé is robust. She’s worked for the nonprofit Hands for Health at its Casas de la Alegría, which care for the children of migrant coffee workers in the area; for the International Migration Organisation, she’s delivered lectures on HIV prevention, condom use, dental care. Now, she works at the border, interpreting, advocating, explaining.

At the time of our interview, she is under acute stress herself. We visit her wooden house, deep in a coffee field, down a plunging dirt road, next to the Río Negro. She tells us how the rains from Hurricane Eta on the night of Tuesday, Nov. 3, swelled the waters to unprecedented levels. The rains that swept away Enrique’s two children washed away Deysi’s home. As we speak, on Nov. 16th, Coto Brus is bracing itself for rains from another storm, Hurricane Iota.

“I live with one eye closed and one eye open,” she says.

To the north

Coffee fields rise from the banks of that river that keeps Deysi awake at night, the Río Negro. From there, they spread throughout Coto Brus. All these fields depend heavily on Panamanian labor—but wend your way to the north and the percentage of Nicaraguan coffee pickers will tick up steadily. So while farmers such as Minor Jiménez have had their gaze firmly on the southern border, even more coffee farmers throughout the country have been looking with rising panic at the northern border with Nicaragua.

Costa Rica is, ecologically speaking, a country of drastic differences and diverse ecosystems, and the contrast between its southern and northern borders fits right in. Unlike the most peaceful border on the planet between Costa Rica and Panama, the Costa Rica-Nicaragua border is highly contentious. While Ngöbe-Buglé migrants are, according to many farmers and industry experts interviewed for this series, often seen as a colorful but quiet part of the backdrop, Nicaraguan immigration is a topic of significant controversy in Costa Rica.

COVID-19 did not improve things. Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega hid away from public view for months as his administration encouraged public gatherings and even anti-COVID marches. A rash of COVID-19 cases among Nicaraguan migrants in fruit-packing plants across the north raised fears among Costa Ricans about Nicaraguan transmission.

So the procedures for coffee migration from Nicaragua look very different than they do down south. One big difference is the legal status of the migrants themselves: the Ngöbe-Buglé maintain a special classification as cross-border citizens, a retroactive recognition of the fact that their traditional territory was arbitrarily split in two by Costa Rica and Panama when the border was created. As such, they are exempt from most migratory paperwork costs. Nicaraguans, however, pay up to $123 for the process, and 20% of each group is subjected to COVID-19 tests as well (Ngöbe-Buglé migrants are tested only if they present a fever during their medical checkup).

“That might be 10% of what they are going to earn in Costa Rica,” says Daguer Hernández, of Immigration. This leads to the other big difference at the northern border: the role played by farmers who cover those migratory costs and, in particular, Coopetarrazú, the country’s largest coffee cooperative. Coopetarrazú Field Manager Felix Monge explains that the entire cooperative, and particularly the entity he coordinates, has been turned upside down by the 2020 harvest. The cooperative produces a whopping 16% of Costa Rica’s total harvest thanks to a workforce that in 2019 was made up of 52% Nicaraguan coffee pickers, 32% Panamanians, and 16% Costa Ricans.

In August, Coopetarrazú leadership realized that “if we don’t get involved, all the way, our producers will end up without their workforce.” Felix says that while conversations with Panana were already advanced by then, especially since coffee to the south ripens earlier than in Los Santos and points north, it was Coopetarrazú that led negotiations to open the northern border and created the protocol that was eventually approved by the Costa Rican government. Nicaraguans board a bus in the southern Nicaraguan town of Rivas and, after their border process, ride that same bus all the way to Tarrazú, where farmers pick them up at the cooperative and take them directly to their dormitories. Coopetarrazú pays for most of this process to lighten the load on its farmers.

“It’s a controlled process, very structured,” says Felix. “I hope that the model this year will be the model for many years to come.”

We witness the last leg of this wearying process late one December night in San Marcos de Tarrazú. A group of coffee farmers waits quietly outside the cooperative; finally, we see a Ticabus holding 40 workers rumble down the hill above us and down into the dirt parking lot. The migrants file off the bus and pick up luggage from the compartment underneath, bags that suggest the range of backgrounds within this group: an immaculate hard-shell suitcase that looks brand-new. A massive bag that once held rice, made of woven plastic strips, that is stuffed with clothes. A pink backpack belonging to a woman who squats with a towel over her head, looking exhausted.

Ricardo Zúñiga of Coopetarrazú bustles around the lot, looking and sounding exactly like the harried director of a summer camp.

“Welcome to Costa Rica,” he says as the migrants begin to get off the bus. “Make sure you pick up your own suitcase, because you are going to very different places… Doña Mireya? Where are going to doña Mireya’s? Come over this way, please.”

We’ve been asked not to conduct full interviews with the tired workers, but are able to ascertain that, like the Ngöbe-Buglé migrants at the southern border, many of these people have been traveling far longer than the 12 hours or so from Rivas. One says he left his home at 10:30 pm the night before.

“I care a lot about these Nicaraguans,” Ricardo says later, after everyone has been successfully dispatched. “The least we can do is thank them… Costa Rica without Nicaraguans is an agricultural economy that’s dead in the water. El tico, the Costa Rican, doesn’t want to work. He wants to be in an office, inside, out of the sun.”

Getting through

The one thing that’s visibly shared among the tired Nicaraguans in the Coopetarrazú parking lot and the Ngöbe-Buglé at the Panamanian border is quiet patience. Mutual stress, calmly borne, is the overriding impression one takes away from these scenes—from Costa Rica’s coffee industry in general in 2020, in fact.

The workers waiting, still, in the main hall. The coffee farmers, much more free to complain and make calls from their position outside, but still fairly silent as they stand and wait. Bus drivers who embrace their unusual protagonism in the process to varying degrees: some are nearly as active in the process as the Cultural Advisors, calling the farmers they represent to coordinate details, rushing about to ensure they’ve got the correct legal papers in the face of changes to the lists of who was expected at the border and who actually showed up. Government officials who, in some cases, are choosing to work 12- or 14-hour days to deal with the onslaught of paperwork.

Monica Quesada Cordero/El Colectivo 506/National Geographic Society Covid-19 Emergency Fund

Máximo, Élida and their daughters eventually emerge from the main waiting room and undergo one final process, at the Ministry of Agriculture building a few steps away, where their bags are inspected and offending items such as fresh produce removed. Finally, they step outside and board a waiting bus that, according to Health Ministry protocols, must take them straight to the farm in Tarrazú—a journey of more than five hours—without stopping, even to use a restroom. There, they will quarantine for two full weeks, under Minor’s responsibility. After that point, they will be free to carry out normal activities; however, for Máximo’s family and many other coffee pickers throughout the country, that normal life is still quite isolated, since they live deep within the coffee fields themselves.

Courtesy/El Colectivo 506

The bus holding Máximo and his family pulls away from a border that is closing down for the night with an uncounted number of migrants left waiting for the next day’s opening, settling down anyplace they can find, including outside, in a roofed area near a park on the Panamanian side. Tomorrow, the people who work here will continue to chip away at the questions that are at stake in this process. How will this year’s events affect binational relations—and the relationships between Costa Rica’s own institutions? How much is the country’s most iconic industry really worth to Costa Rica, and to the people who make it run? And how sustainable is its migrant worker pool—which depends, by definition, on the living conditions its members experience back home, and their motivation to make a long trip each year in order to work elsewhere?

Máximo still wants to know when his family will lie in a bed again. The trip home isn’t a smooth one. The winding road through the Cerro de la Muerte, or Hill of Death—so called because travelers on foot or on horseback sometimes died of cold on its upper reaches, at more than 10,000 feet—is completely closed at one point. Máximo and his family have to sleep in the bus, not knowing if they’ll be able to make it through in the morning. (“It was an odyssey,” Minor says of his workers’ final leg.)

Somehow, and they don’t know why, the road opens just before dawn. At about 5 am, 48 hours after leaving their home in Bocas del Toro, the Palacios family are home again—or home in a different way. They are walking down the dirt road that dips through a shallow stream, takes a turn to the left, and ends at a zinc-roofed house perched on the side of the Talamanca mountains. They are glancing out at the familiar valleys swathed in clouds; passing through the outdoor fireplace area where they’ve served up many a meal; opening the door to the enclosed area that holds bunk beds they’ve known for years. They are surrounded, finally, by the glossy coffee plants that have been calling their names over so many miles, all these long hours.

Next in the series: Life in the coffee fields, and how COVID-19 has changed it – for better and for worse.