“What is the topic of the day? Let’s see”, says teacher Marcela Aguilar Alpizar to the students of section 11-2-A of the Liceo San Rafael. The dozen students, sitting at their desks in a classroom that has been split in half by a gypsum wall to make the most of every inch of the already overcrowded public school in Alajuela, carefully watch the television screen displaying their teacher’s presentation.

“Do you think this is dangerous?” Marcela asks, as she reveals each new image. These include a banana peel on the floor, a mosquito, a ghost. Her conversation with her students, conducted entirely in English, is increasingly lively, reaching a peak when they discuss whether or not ghosts exist, rather than whether they are dangerous.

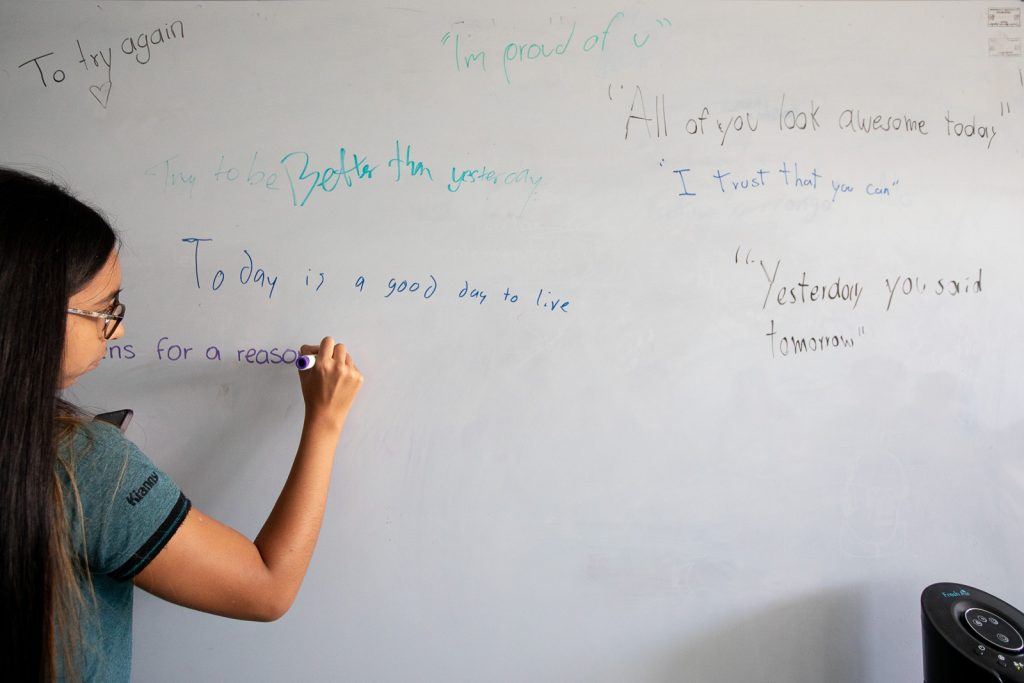

The last image is the word “words.” Today’s theme: words and their power.

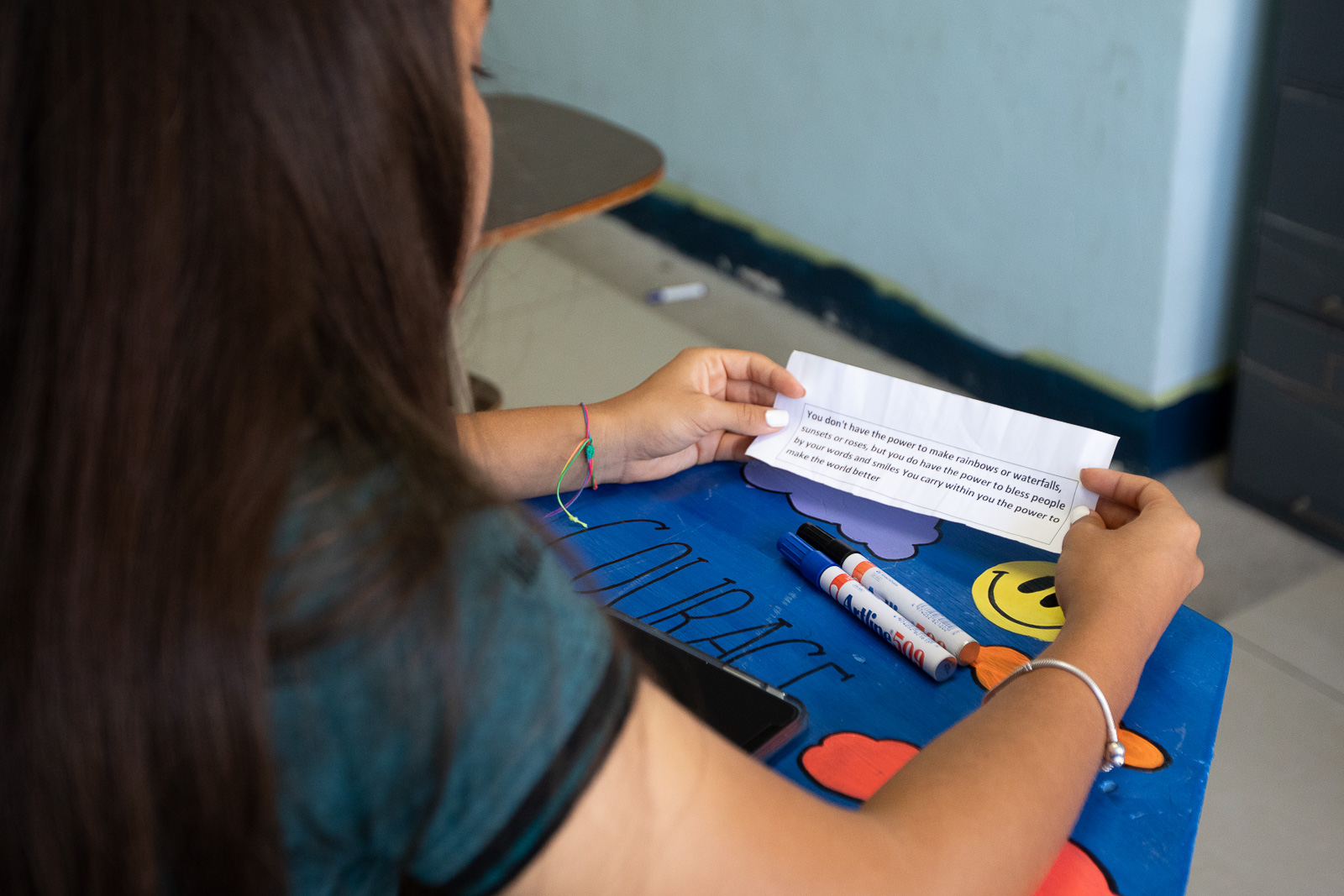

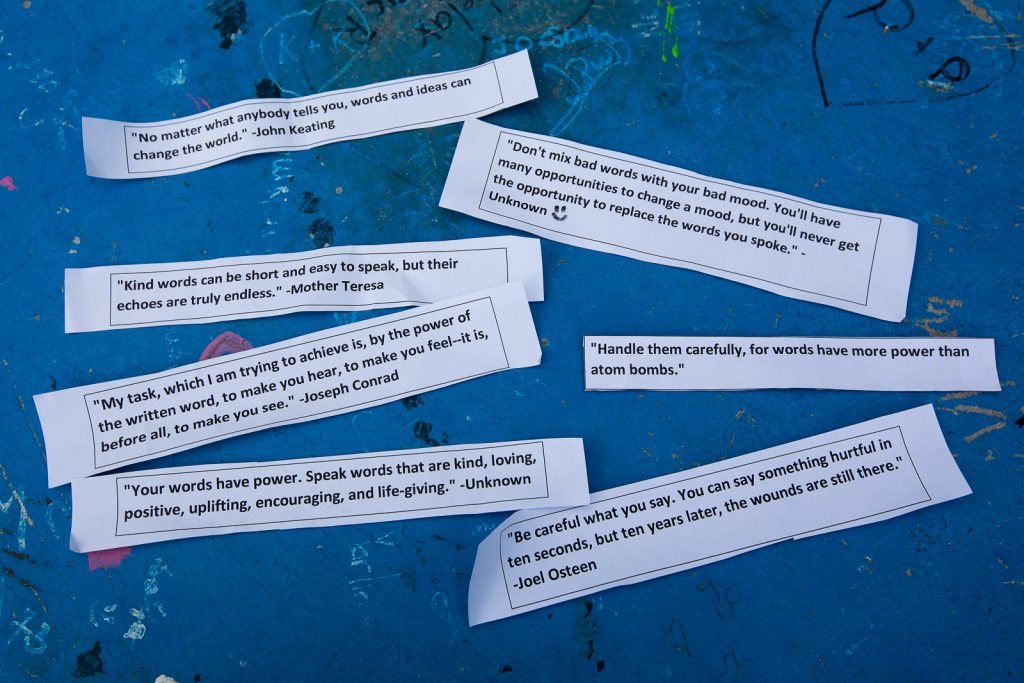

Section 11-2-B is undergoing the same activity, but with Alfonso Moreira Fallas, who now gives them a series of quotes in English on pieces of paper. He invites his students to mingle, heading out of his half-classroom onto the patio. While the teacher plays “November Rain” by Guns N’Roses on the speaker in his hand, the students have to walk in all directions. When the music stops, they have to make groups according to Alfonso’s instructions: for example, “Form a group where only one person has a wristwatch.” Once in the group, they must explain to each other what the quotation they are holding in their hands means. Alfonso jumps from one group to another encouraging them to talk, always in English.

Sections 11-1 and 11-2 of Liceo San Rafael are bilingual English-Spanish sections. In this high school, all levels, from seventh to eleventh grade, have two groups under this modality; this institution is one of the eight high schools in the country that offer this type of training. According to the Ministry of Public Education (MEP), about 2,000 high school students in Costa Rica are now participating in bilingual sections. Of the nearly 1,600 students at Liceo San Rafael, 303 are in this category.

“Spanish-English Bilingual Sections were initiated by the Department of Third Cycle and Diversified Education,” explains Mariana Granados, National Secondary Advisor of the MEP, in a written response to questions from El Colectivo 506. “In 2017, we began its pilot phase in six schools: Nicoya High School, Colorado High School, Higuito High School, Santo Domingo High School, Sinai High School, and San Rafael High School.

In 2021, “In 2021, after five years of piloting, through Agreement 03-54-2021, the Higher Council of Education firmly and unanimously approves the consolidation of the Spanish-English Bilingual Sections as a formal educational offer and ceases to be a pilot project from the year 2022.”

The eight institutions that offer these sections are located in the Regional Directorates of Education of Heredia, Pérez Zeledón, Desamparados, Cañas, Nicoya, Liberia, Alajuela, and Coto. This means that there is at least one high school in all the provinces except Limón.

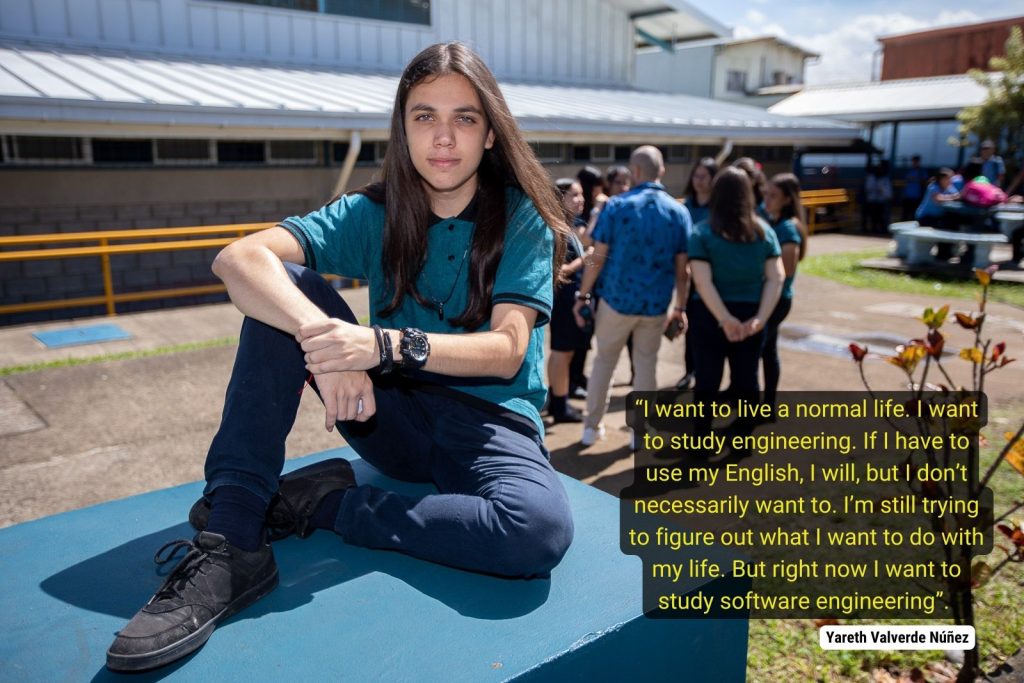

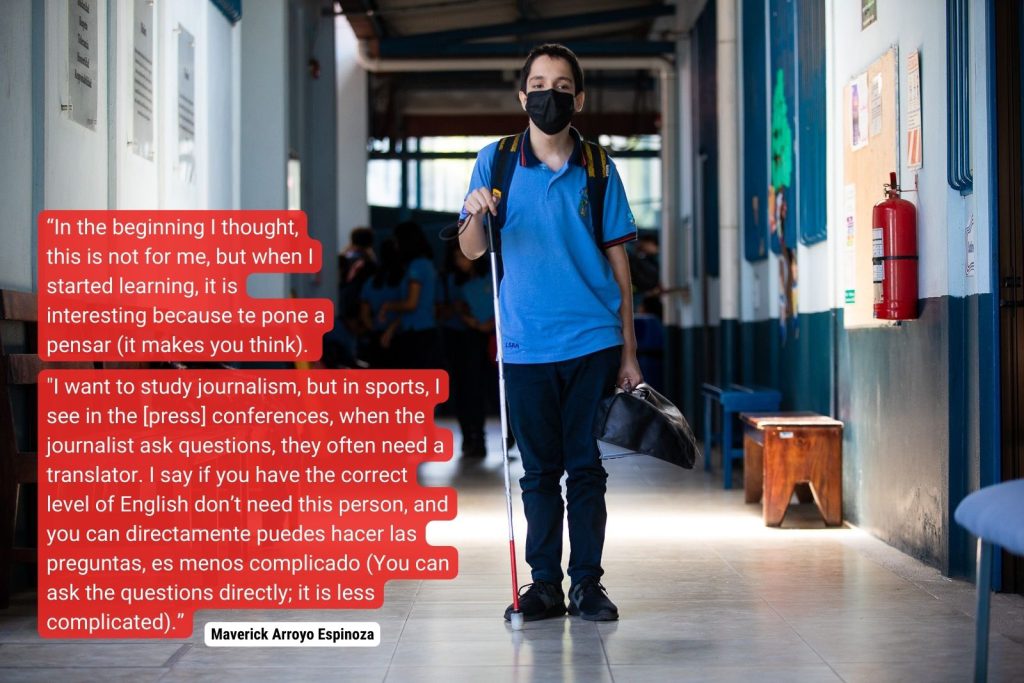

Yareth Valverde Nuñez is a student in section 11-2-B. He arrived at Liceo San Rafael in 2017 at the urging of his father, when the bilingual section pilot project was just beginning.

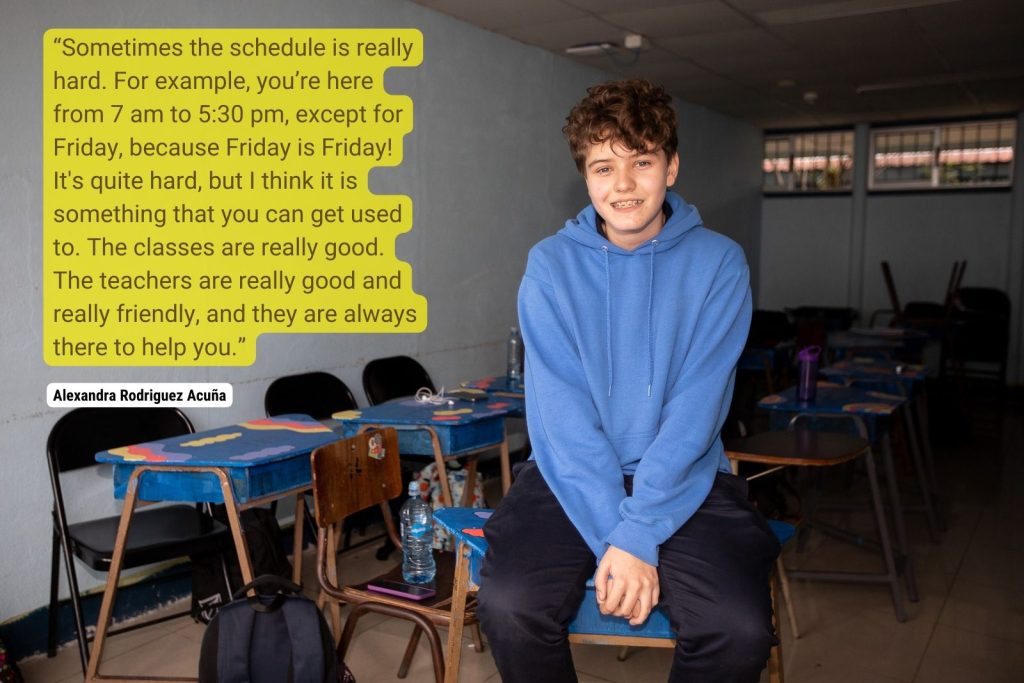

“It was a little bit harder in seventh grade,” says Yareth in an interview entirely in English with El Colectivo 506. (I have recorded the English of the students exactly as they spoke so that you can enjoy, as I did, their authentic and enthusiastic self-expression.) “It was a little bit harder in seventh grade because there was a time where we were going to our home to 5:45 and it was really hard. Only one day we were going out at like 4pm. It was really hard, but I sorted it out. Right now I don’t feel it is hard: it’s normal.”

Overcoming the difficulty of committing to a more demanding high school education caused Yareth to repeat ninth grade. Although he was unable to graduate with the first generation of the bilingual section of his high school, today he is a convincing representative of the results of a bilingual education.

“There is some people that is a little behind, but everyone understands English,” Yareth says when asked if all his classmates speak the language that well. “If you speak English, they would understand.”

Yareth is the first person in his family who speaks English, and he has been the inspiration for his younger brother who, at the beginning of eighth grade this past February, decided to switch from traditional academic education to the bilingual section of the high school. He discovered that he wanted to be able to speak English like his brother, who has been teaching him now for more than five years.

“I watch movies in English. Everything I have is in English. That is how I learn English,” says Yareth about how he has polished what he learns at school. “I learned a bit of English before entering high school, and thanks to my dad right now I have the opportunity of being here.”

How do bilingual sections work in public schools

The short answer is: many hours and a lot of work.

In addition to the normal academic load of any school, students in bilingual sections must complete an extra 14 lessons per week, entirely in English. Every day, they receive two English lessons. For these lessons the groups is divided in half to encourage participation. In addition, twice a week, the entire section receives two English literature lessons, through which they delve into the language.

In addition, the bilingual sections receive extra computer classes for the bilingual section, and talent development classes, which at Liceo San Rafael are theater, dance or music.

“Yes, we come from 7 am sometimes to 5pm. So it’s really hard, you know, but I think it has benefits,” says Mariana Corella Calvo, Yareth’s section partner. She, too, answers entirely in English.

“At the end of the day you get too exhausted, but then you think: it’s for your future,” Yareth adds immediately.

Mariana entered the 11th grade bilingual section of Liceo San Rafael in 2022. Like Yareth, Mariana is the only person in her family who can speak English.

“I’m really new to this. I never even knew that there were schools that have bilingual sections, so I was really impressed,” says Mariana. “I think this is something really good for students that really want to make a career out of this, so they can speak English. I was in a private school, I have been in a private school all my life, but since COVID and everything, I came here.

“I can tell that the teachers here really love their job, and [Yareth] is an example” of the impact, she adds. “He’s a really good English speaker, so it was really nice to see.”

Despite being new, being surrounded by people with the same goal allowed Mariana to adapt very quickly.

“So Yareth and I, we have this kind of relation that we only speak English with one another,” she says. “You know, I love English and he loves English, so we try to speak more English than Spanish because we really wanna practice.”

“It’s a really nice experience,” says Juliana Sánchez Sánchez, coordinator of the bilingual sections program at the high school. She’s also an English teacher for the ninth-year bilingual sections and English literature for the 10th-year bilingual sections. “Before coming here I was working in private schools, and there you teach everything: grammar and oral, separated, and one teacher has emphasis in one of the areas. But here you have to put everything together. You have to teach them real English. You have to integrate the 10 lessons they have per week. You have to teach them a little bit of this, or a little bit of grammar, like implicit grammar and different skills, and it’s really nice.”

When Juliana started as a teacher at the MEP in 2017, she did so as an English teacher for academic degrees. Along with her experience as a teacher in private institutions, she speaks freely about the different ways a student can learn English in Costa Rica.

“In three lessons, there is no time to integrate all the skills,” says Juliana about the English instruction that MEP’s regular academic modalities receive. “You have to emphasize some content and just move on, because you have to finish the program. But when you move to bilingual sections, it’s just like, ‘This is what I was waiting for all my life.’ You can integrate the skills, you can work with different activities, you have a lot of time to fill the students with different things. They speak English, and you can ask them to speak English. In academic lessons you can try, but there is no time.”

The impact of the English lessons increases through the English literature class.

“We learn about some historical British or United Stadien person, like a writer,” explains Yareth. “Everything is related to… How do you say this… historical… how do you say… ah! Literature history.” This is the first time that Yareth finds himself up against the wall trying to explain something in English, casting about for “literary history.”

“Like Shakespeare, all the great masters of literature—we study all of that, and we study how to make a story or how to understand a story,” he finishes explaining.

“We write a lot,” says Mariana. “A lot!” Yareth echoes.

But at the end of the day, it is those classes and their teachers, like Juliana, Alfonso and Mariana, who motivate them to continue.

“He makes the classes very fun,” Yareth says of Alfonso, the English literature classes he teaches twice a week, and the English classes he takes every day. “That’s why I come every day.”

What impact do bilingual sections have on public schools?

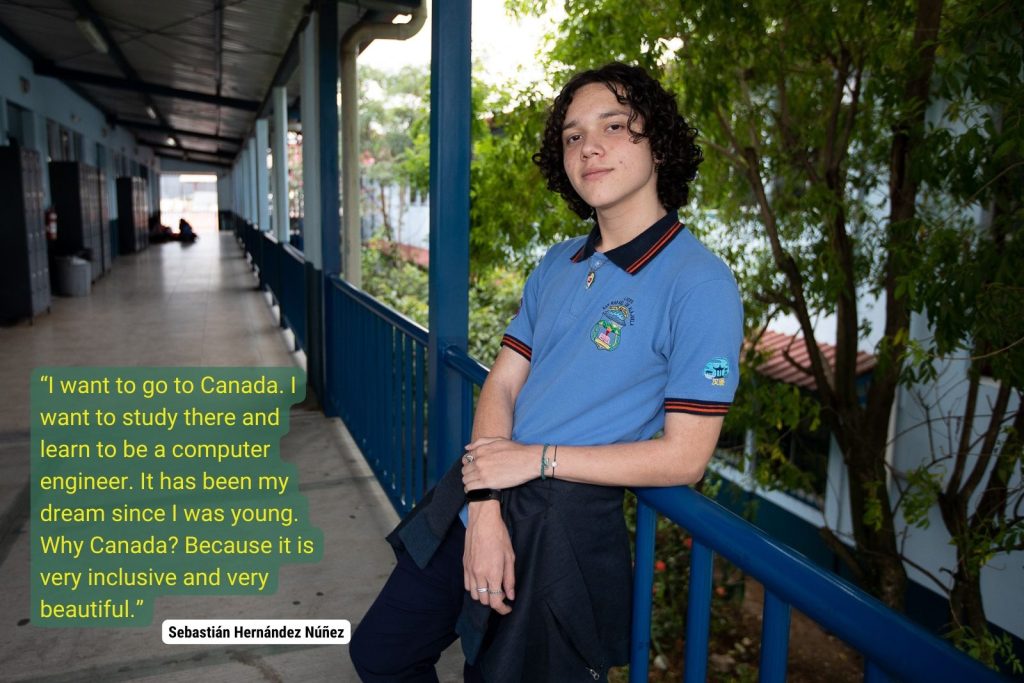

“The creation of bilingual sections opens up to the communities a range of real opportunities in academic schools to choose and enhance the linguistic and communication skills of the learners, with a balanced curricular proposal in socio-interpersonal, transactional, academic, professional and artistic,” says Mariana, the MEP national advisor. “It is presented as a response to reduce the gap between private and public education in order to open a range of opportunities for disadvantaged local populations.”

Now, could it be that this is a more viable response to reduce this gap?

The Report on the Results of the Linguistic Domain Tests (PDL) of the University of Costa Rica, which in 2021 measured the level of command of the English language in eleventh-year students throughout the country, both in the public and private sectors, says yes.

How Costa Rica transformed the way it assesses its English students

“Finally,” reads the report, “student performance for the bilingual sections should be highlighted. Their performance is similar to populations such as students from Bilingual High Schools or private schools in which the A1 band has the least number of students. In the case of the bilingual sections, 46% of the students evaluated are in the higher bands, 43% in the B2 band and 3% in the C1 band.”

The same report shows that private schools have 49% of their students in band B2 and 18% in band C1. The Experimental Bilingual High Schools have 39% of their students in the B2 band and 9% in the C1 band.

What limits its growth?

As explained by Mariana, the MEP Advisor, in her written response, “about 50 academic schools have requested the opening of bilingual Spanish-English sections.” “In the eight educational centers that currently offer it, they have high demand from parents who want their children to be able to enter.”

However, according to the advisor, the main obstacle they face in improving supply is the ministry’s restrictions and budget cuts, especially in recent years.

She adds that “the goal is to have at least one academic college with a bilingual section for each regional education department”—that is, to reach a total of 27 institutions with bilingual sections. “It is clear that in those geographical areas with a high population density, this number could be significantly exceeded so that bilingual education becomes even more democratic.”

Who enters and who does not enter a bilingual section in public schools?

Unlike admission to bilingual preschools now offered by the MEP, admission to bilingual sections is not a lottery.

Starting small: Costa Rica creates language immersion for public preschools

The admission process depends on the result of an exam developed and organized by the MEP’s Quality Management Division. That exam tests analogies and reading comprehension in Spanish. That is the only requirement. Unlike the academic levels, it is not necessary to live in communities attached to each high school. Anyone, from anywhere in the country, can apply for a place in any of the eight institutions that offer this modality.

Juliana explains that the Liceo San Rafael admits 75 students in seventh year in the bilingual sections. The first step in the admissions process is to call on students in neighboring elementary schools and spread the word in the communities. Interested people must register and then attend a parent meeting that, this year, just happened in the month of July. A total of 152 people signed up for this meeting, and more than 100 attended.

After this meeting—which will take place between August 1- 5 for Liceo San Rafael—the documentation of the students who are applying for each institution is received. This information is entered into the system by the coordination of each high school so that interested students can be included in the admission test.

In the case of Liceo San Rafael, the department offers a preparation workshop for the test, so that the technical part of filling out the answer sheet and understanding how to answer the questions, especially analogies, is not an obstacle to the students.

Students with the top 75 results on the admissions test—which also includes a percentage of their primary grade point average—will be guaranteed a spot, but many ultimately decide not to enroll. All the other people who have applied will constitute a waiting list in descending order of admission grade. Enrollment closes when the quota of 75 students enrolled is met.

Admission to the bilingual sections at any other level, as is the case with Mariana, depends on the availability of places in the groups, which must not exceed 35, and the level of English of the new student. To determine if they have the appropriate level, the bilingual section’s department at the high school conducts a placement test.

“I personally tell them, make the decision as a family,” says Juliana, describing her advice for families who opt for this training for their kids. “It’s a huge satisfaction to know that at the end [of high school] I speak English, but maybe at first the kids don’t feel that way. What they see is a schedule full of classes: ‘I’ll be there every day from sunup to sundown!’ So they get scared. Make the decision thoughtfully, and know that your sons and daughters are valuing the English that they are going to receive. That they are going to take advantage of the opportunity.”