The final installment in a two-part series on the impact of the Law Against Animal Mistreatmen, which included reforms to Costa Rica’s Animal Welfare Law and Penal Code, since its signing in 2017. Read the first part about the law’s provisions for complaints, fines, and trials against people who violate it.

“He has a 100% normal life,” says Isabel Aguilar when I ask after Campeón. “He’s super healthy, super chubby.” Isabe is a lawyer who, as we reported in the first part of this series, jointed forces with Dora Castro Herrera, president of the Athenian Foundation for Helping Abandoned Animals to rescue Campeón from an abusive situation in 2017. Isabel has also taken care of Campeón ever since. Today, he is a member of his pack of 17 dogs.

“There are still two things in this world he can’t tolerate. One is wearing a collar, which I assume is because of what he experienced,” she explains. “And he is terribly afraid of water, of showers. There’s something he’s terrified of.”

The story of the trial for the mistreatment of Campeón had an unexpected ending. However, Isabel says that not everything was lost.

“Just the fact of sitting that woman [Campeón’s former owner] down in a courtroom and the public scrutiny, is a win,” says Isabel. “In addition, I set a precedent in this country. Campeón was the first dog in all of Latin America to attend a trial. He behaved very well!”

Isabel’s stance is shared by all those interviewed by El Colectivo 506 for this series on the impact of the Law Against Animal Abuse, signed in 2017.

“We can see this as a glass half full or half empty,” says Dr. Iliana Céspedes, of the Animal Welfare Program of the National Service for Agrifood Health and Quality (SENASA). “There is greater awareness among people that harming animals is not right; it’s more visible now. There is more media support, and that makes some situations go faster and better.”

“It is a pioneering law,” says Juan Carlos Peralta, president of the Association for Animal Welfare and Protection (ABAA). “This is futuristic. We are building [law enforcement efforts] together, and old folks are making this effort because we are doing our part.”

The lessons, achievements and limitations of the application of the law in these four years and 10 months since it took effect are many. They include increased awareness, insufficient budget for enforcement, and the need for increased training for public servants.

What has been achieved with the Law Against Animal Abuse?

“It was necessary,” says Dr. Ninuska Key, Prosecutor for the College of Veterinary Physicians, when I ask about the impact of the law. “This was a gray area. The animals were unprotected, with no law to protect them and guarantee their needs would be met.”

Before 2017, Costa Rica already had an Animal Welfare Law (1994); its Article 3 established the basic conditions for the care of domestic animals. However, one of the changes caused by the Law Against Animal Abuse in 2017 was its Article (21), which establishes sanctions and fines for people who do not meet these basic conditions. These conditions include “a) Satisfaction of hunger and thirst. b) Possibility to develop according to normal behavior patterns. c) Death without pain and, if possible, under professional supervision. d) Absence of physical discomfort and pain. e) Preservation and treatment of diseases.”

“Responsible ownership is up to owners,” says Iliana from SENASA, adding that she has observed definite impact since 2017. “There is progress in terms of the consequences for harming an animal today. There is a greater opportunity for people to be held accountable, and greater empathy from people or institutions regarding this topic.”

As we reported in Part One, the number of complaints received by both SENASA and the OIJ have been increasing, along with the number of cases that go to trial.

Steeven Paniagua Mora, an investigator from the Judicial Investigation Organization (OIJ) in San José, is one of eight people in charge of dealing with complaints of animal abuse in the province. In addition, he ensures that Costa Rica’s other delegations and sub-delegations assign investigators who deal exclusively with these complaints.

“In my experience, the most common crimes are poisoning an animal,” says Steeven. “Like any other crime, we investigators must visit the site, look for witnesses, observe the situation. Whether or not the animal survives [the poisoning], we seek support to extract samples to take to the toxicology department [of the OIJ], along with what has been detected on site. If it is a deceased animal, a necropsy is done; samples of stomach contents are taken, as well as certain organs to determine the poison used, and whether it matches what we found at the scene. Through this investigation, we ascertain who was responsible.”

To achieve this, the OIJ has had to assign not only personnel like Steeven, but also services such as the department of toxicology. In addition, Steeven reports that the OIJ has signed an agreement with the San Francisco de Asís Veterinary School so that they can perform necropsies on dead animals.

“There are many veterinary practices that also offer to collaborate,” Steeven says. He adds that the OIJ’s collaboration with SENASA has been essential. “We complement each other very well because we have investigative and police knowledge, and they have veterinarians who can do a primary assessment on site.”

“[The law] has had a positive impact. It’s moving along. It is a process”, says Juan Carlos, from the Association for Animal Welfare and Protection. “There are very few countries in Latin America that have these standards, and that have been able to take cases to trial.

“You can see [the progress] on social networks, how people are outraged when an act of this type takes place,” he adds. “Sadly, most people believe that making a report through Facebook is enough.”

What obstacles are faced by the Law Against Animal Abuse?

“We still have no budget, ever since 2017. We’re owed a lot: budget, personnel, vehicles, a place to take the animals to be evaluated and cared for”, says Iliana, referring to the lack of follow-up and interest from the Executive Branch. “We once had a case of 300 cats. What do you do without a place to take them, without having a budget to take care of them and feed them?”

According to many of the people interviewed by El Colectivo 506, the lack of funding is the main stumbling block for the institutions that must enforce the law. However, they add that the lack of budget is compounded by the lack of training and education of the personnel in charge of these cases.

“A budget is needed. and a department, someone to take care of this at the national level”, says Ninuska. “A department with a structure that allows us to cover the entire country, because we are not only talking about domestic animals.”

“In this country, you know who the vulnerable populations are,” explains Iliana. “To care for children, it’s the PANI. To care for women, it’s the INAMU. For the elderly, CONAPAM. But it turns out that when it comes to animals, responsibility is given as a double load for an institution that already has a responsibility: if SENASA neglects safety, we human beings get sick.”

As we pointed out last week, SENASA’s responsibility to ensure the responsible ownership of pets comes from the Animal Welfare Law and the project that Iliana has led since 2012. However, as we already mentioned, this team was trained for another purpose altogether.

“In 2017 they gave [SENASA] the responsibility, because we are the institution with the most veterinarians in the country, but veterinarians are trained for safety,” explains Iliana. “It is not just a veterinary issue. The vet part is the easiest. The problem is that this dog also has an owner; the people who filed the complaint also have expectations, and they must also be attended to. We are good veterinarians—we are not social workers.”

In the case of the veterinarians’ guild, Ninuska explains that a veterinarian can intuit when an animal could be the victim of violence or irresponsible possession: “The one who’s been bitten by another dog and comes back again, and is missing another piece. Malnourished animals. You can figure it out.”

However, she explains that the College of Veterinarians has no protocol to guarantee vet safety when filing a complaint.

“We need that firm tier that watches over the integrity of each veterinarian, the confidentiality of our actions,” she says. “There is a lot of fear.”

Ninuska also explains that there is a misconception that the College of Veterinarians is responsible for taking action against irresponsible possession or animal abuse: “Structurally, internally, there are flaws. Someone from OIJ called me about the issue of the dog who’d been hanged on the train tracks? I don’t know what to do, either.”

“Incredible, almost five years after the law has been in force, and there is still a lack of knowledge of the norm,” says Juan Carlos of ABAA, referring to occasions in which complaints have been filed with the OIJ and the reaction has been insufficient.

Steeven, from the OIJ, says that the people in charge of these complaints have been selected not only for their experience as investigators, but also for their affinity towards the victims of these crimes. He says OIJ staff have not noticed any shortcomings.

“We have not felt so much that the resource is so lacking, because we have great support from other entities,” says Steeven, referring to the work with SENASA and the San Francisco de Asís Veterinary School.

“Time and experience”, says Steeven when I ask him what needs to be done to make the law more effective. “The more time and experience we have, the better we are going to handle the cases.”

Both Ninuska and Iliana say it takes more than time. They say it’s important to create a team or institution that is dedicated to this work. However, in a country with serious public funding problems that have been worsened by the pandemic, this may not happen.

“It would be so interesting to have a system like the traffic [police]”, says Iliana, mentioning one of the many ideas they have come up with when they try to find a solution to the lack of resources and the low rates of collection of the fines levied by SENASA. “We have many ideas—for example, handling complaints be handled in a call center, like SINAC [the National System of Conservation Areas] does. But for that, we need money.”

“It’s a lot of work that has to come from Casa Presidencial,” says Ninuska.

“If there was political interest, this would move, because we are all employees,” says Iliana.

What can citizens do to make the Law Against Animal Abuse more effective?

The first step is to get informed.

This education process begins with knowing and recognizing the responsibilities that the law attributes to all owners of domesticated and domesticated animals. In a previous section we mentioned the minimum requirements established in the Animal Welfare Law’s Article 3, but there’s also plenty of information available about the sanctions people can face if they fail to collect pet feces in public places, or if they breed or train animals to be violent.

In the field of prevention, the people interviewed agree that educating kids is key.

“You have to do awareness campaigns. You have to get to the children’s classrooms. We must rescue principles and values. You have to train”, says Ninuska. “I wish there was a restructuring at the level of education where we talk about animals, care, why it matters—including productive animals, which also deserve respect.”

However, the public must also learn how to report these offenses and other animal welfare violations.

“The problem is, where do I complain?” says Ninuska, “It is not in the College [of Veterinarians].”

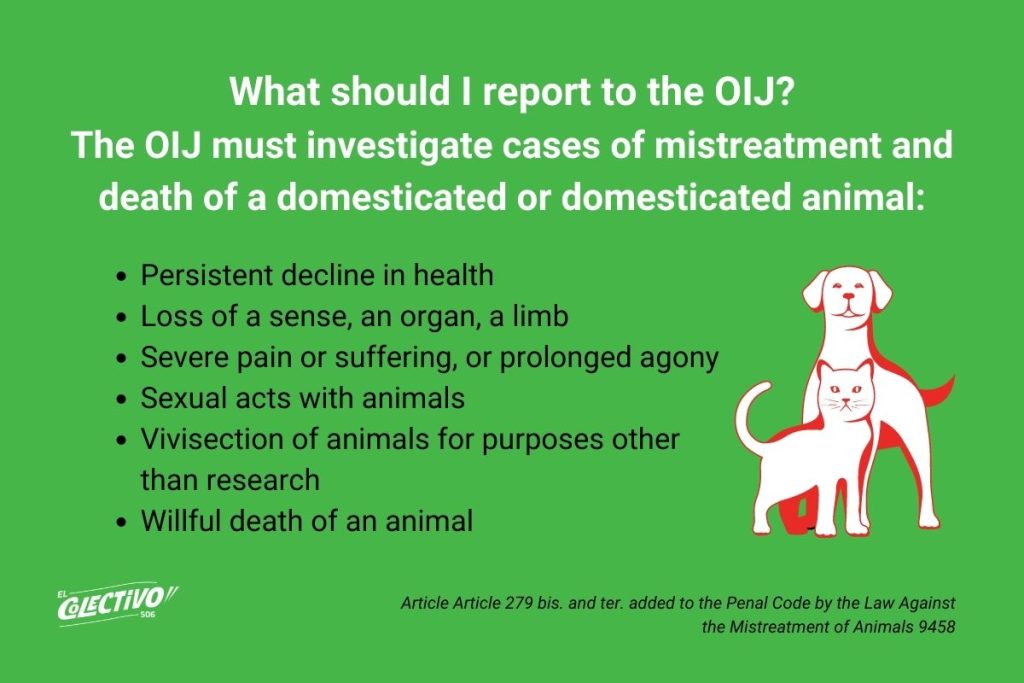

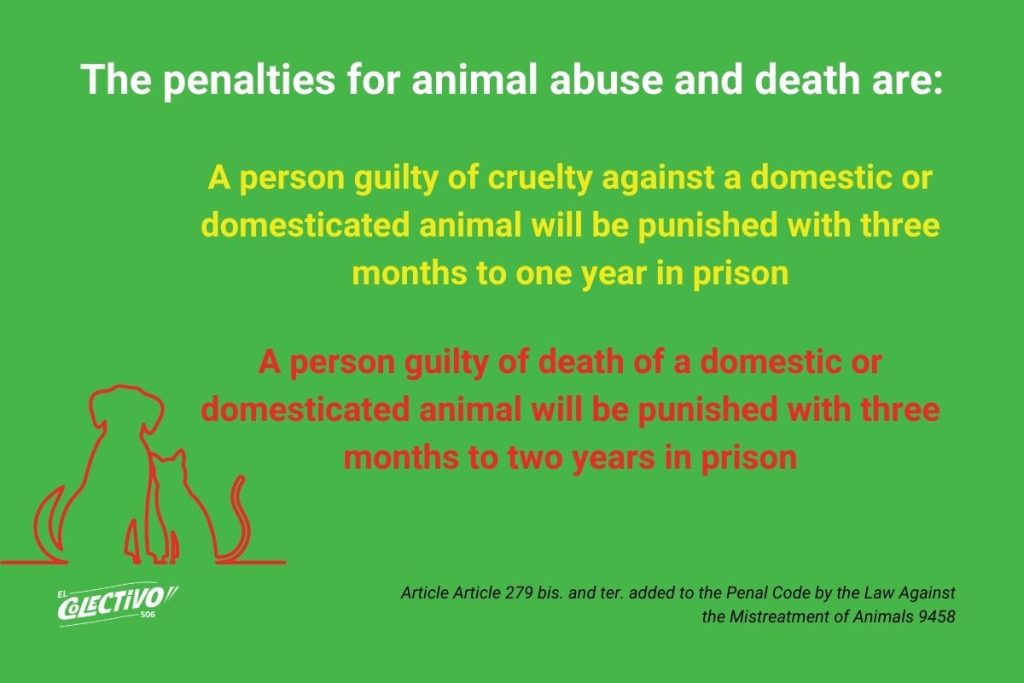

Complaints that have to do with irresponsible animal ownership—that is, violations of Article 3 of the Animal Welfare Law—should be directed deben to SENASAWhen there is mistreatment, cruelty or death, that’s a job for the OIJ.

Steeven clarifies that people can choose various ways to file their complaint with the OIJ. They can file a formal complaint with the OIJ, just as when a robbery or assault is reported at any of its offices, or by sending an email to [email protected]. Also, they can choose to submit information confidentially by calling 800-8000-645 or WhatsApp 8800-0645, if they want to share images and videos. The OIJ is in constant communication with SENASA to deal with complaints that are made in one entity, but are within the other’s jurisdiction.

“We do not only act on complaints,” adds Steeven: his team also investigates what is published on social networks and information they receive through other unofficial channels.

“Citizens must file a complaint to create pressure within the Public Ministry,” says Juan Carlos of ABAA, who believes that this pressure is what will force officials and institutions to learn about the rule and apply it.

A clear message

“I still think that when it comes to filing a complaint for animal abuse, they see it as a zero on the left. They tell you from the first entry that this is not going to amount to anything,” says Isabel at the end of our conversation that began with the Champion story. She, as a lawyer, continues to file complaints in the Atenas courts for other cases of animal abuse in that town.

Like Juan Carlos, Isabel believes that pressure from citizens to comply with the law is key, but for that, people must be informed.

“When an animal is killed, the prosecutor and the OIJ have to come to remove the body and document it,” says Isabel. “But when I call and ask for this, they tell me that ‘it’s not up to us.’ ‘Oh, the prosecutor says no, that it is not necessary to go get the body.’

“It’s up to us to change this, like what an association did and said, ‘We’re not leaving until the OIJ arrives,’” says Isabel, referring to a recent case where a dead dog was found in a bathroom in unsanitary conditions. “That is the only way: for people to demand that their right to a process be fulfilled.”

Based on her experience with Champion, who was unable to see justice applied to his aggressor, she knows that citizens’ work must continue to the end.

“The people who want something done, for real, have to know that it’s not just a matter of calling and complaining, and then disappearing when the key moment arrives,” Isabel says. “The witness who backs out tomorrow: instead of helping, that person made it even worse, because you showed the [owner] that what he did will not have an impact.”