Can you imagine being surprised by a raging flood in the middle of night?

Knowing that the worst is yet to come, but not knowing what it will be like? In the middle of the darkness, hearing the trees fall, cries for help, the water head breaking everything in its path? Trying to survive while the water is up to your knees?

November 24, 2016 will be a date that all upaleños will carry with them for life. That day, Hurricane Otto arrived without warning and left billions of colones in losses throughout the canton of Upala. Some of us had just enough time to find a safe place until the water subsided. In other cases, sadly, the water head and mud flow took their lives. Ten people died that night.

In a moment, the efforts of hundreds of residents of this humble canton were buried amidst mud and dirty water. They lost everything.

The passage of Hurricane Otto exposed the factors of vulnerability to which the inhabitants of this community have been exposed for years and, in turn, the need for institutions and communities to improve their risk management in terms of planning and organization.

The immediate palliative solutions of that event were significant: according to data from the National Emergency Commission (CNE), 4.5 years later, about 10 billion colones (USD 16 million) have been invested in the reconstruction of bridges, dams, roads, schools, aqueducts and sewage systems that were totally destroyed in this canton of the northern Huetar region of Costa Rica.

However, authorities also identified the need to find solid solutions to reduce the risk of the population and, of course, avoid greater losses during future natural events.

I was part of that process. I worked as a press officer in the Municipality of Upala between the years 2017-2020, and was also in charge of public information for the Municipal Emergency Committee of Upala during that time. From that position, I could see how international institutions and organizations began to merge efforts. Now, as a participant in Network 506, I was able to return to the subject and look at it with new eyes, to see how the work has evolved to achieve a more prepared and organized Upala.

The questions facing the community and authorities in the days following the 2016 event were simple and urgent. How could this despondent community ensure that its night of horror would never be repeated? Or, if the waters were to rise that high again, how could we ensure that this time, we would be ready?

Communities used to ‘little floods’

The area devastated by Hurricane Otto, near Lake Nicaragua and home to renowned tourist destinations such as the Rio Celeste, is used to instability. Those of us who live here know that the area is highly exposed to weather, consistently flooded, and surrounded by the imposing Tenorio, Miravalles and Rincón de la Vieja volcanoes. At least, in the districts of Upala, Delicias, Yolillal and San José de Upala, there are frequent floods on the plains.

Our grandparents say that for years they have managed to live with the “llenas” caused by the Zapote River. They’re used to seeing the water run through the main streets of the town. It was common to see little ones playing barefoot in the flooded park.

However, before 2016, this border canton never expected to be struck down by a crisis of such magnitude. Despite constant flooding, earthquakes, landslides, and volcanic eruptions, the community that came together after Hurricane Otto had to acknowledge that it was never prepared for a major disaster. That was one of the strongest and most difficult realities to assimilate: the failed local response.

It failed because of the limited capacity of the Municipal Emergency Commission, at that time, to deal with the level of devastation that was approaching the area that Thursday night. At least, that’s how the situation was characterized in a report from a special audit that the Comptroller General of the Republic (CGR) conducted on the management of Community Emergency Committees.

Furthermore—despite the fact that that day, local authorities issued evacuation notices to the population and area businesses— the megaphones, radio messages, and social network posts were not effective in achieving the evacuation of vulnerable populations. Some families that were alerted preferred to stay at home, but media organizations such as La Nación, which touted the area hours after the impact of the hurricane, found that the message did not reach the entire population equally. During a visit by Semanario Universidad to the disaster area, several residents said they had not received any type of warning.

“Never. In this area, we were not asked to evacuate. We left by our own means. My cousin was the one who passed by and warned me, and we got out just in time,” José Vinicio Quesada told Semanario Universidad in the El Rosario neighborhood, about a kilometer and a half from the center, one of the areas most threatened by the Zapote River.

While evacuations on the Caribbean coast were carried out with police assistance, in the Northern Zone, everything was left up to the population. Shelters were activated, but few considered it necessary to go there before the hurricane arrived. The Comptroller’s report noted the absence of community emergency committees and a failure to follow the risk management structures recommended by the National Emergency Commission in terms of management being followed up.

After Otto, various institutions—local and central government entities, and international organizations—pooled financial, scientific and professional resources and began generating ideas about how to build local capacity for future emergencies. An example of this was the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), which identified the absence of community emergency committees (CCE) in risk areas. The organization focused on building capacity in community leaders, those who know better than anyone the vulnerability of the neighborhood and who, in the midst of an emergency, become immediate community leaders.

The inter-institutional work that followed the hurricane generated two conclusions. First, it was necessary to strengthen the Municipal Emergency Committee (CME), made up of all the representatives of the institutions with a presence in the canton and headed by the Local Government, and set up community committees hand-in-hand with residents.

Second, once organized, these entities would require tools to identify threats and be able to carry out their work in the face of future storms and floods. To meet these two needs, at the beginning of 2018, the Early Warning System (SAT) took its first steps.

Sounding the alarm

The SAT is a technical-scientific project that involves communities so that, knowing their most vulnerable areas, they are prepared to provide an immediate response as leaders in an emergency.

This initiative was developed so that it can be transferred from generation to generation, with a special focus on community empowerment.

UNDP and the Costa Rican Institute of Aqueducts and Sewers (AyA) joined forces to provide technical assistance to community emergency committees and support the development of the Early Warning System for hydrometeorological events in Upala. For the system to be effective, two elements were critical: the hydrological station, and close coordination between local authorities and communities.

One of the components, the Upala hydrological station, was the first of its kind to be installed in Costa Rica. It contains a sensor that measures the level of the Zapote River; it is located on the Canalete Bridge and can be monitored in real time by anyone, via a web page. The water measurements are updated every five minutes, which allows a strict control of the river.

The National Meteorological Institute (IMN) regulates the station and maintains constant communication with the Municipal Emergency Committee, the community emergency committees, and regional liaisons from the National Emergency Commission.

Wilson Espinoza Cerdas, vice mayor of Upala and operational coordinator of the Municipal Emergency Committee, explains that the warning margin—that indicates that the center of Upala could be flooded—occurs when the sensor registers -5.8 meters or less between the bridge and the water.

From that moment, an early warning protocol warns the population of the center of Upala that they have between 45 minutes and 1 hour to try to protect their belongings, remove items, and find a safe place while the water drops. As soon as the alert is generated, authorities sound a siren at the Municipality of Upala is activated, along with the sirens of local emergency entities.

“With the first rains in June this year, we experienced significant river flooding. The sensor generated an alert indicating that the water was reaching -5.24 meters,” said the vice mayor. “Thanks to the fact that the head of water lost strength along the way, the water did cross the road, but it did not cause major inconveniences.”

The objective of the hydrological station is not to prevent floods, but rather to alert the most vulnerable population in central Upala and surrounding areas about sudden flooding, thus reducing the direct impact on citizens.

“We have advanced significantly. We are even working to be able to synchronize the sensor with the siren that we have in the center of Upala. Currently what we do is that as soon as the alert is given, we activate the siren manually,” Wilson says.

Although no evacuations have been necessary since the installation of the station in November 2020 part of SAT Upala, the Municipal Emergency Committee and the community committees maintain constant communication about water levels.

The power of the people

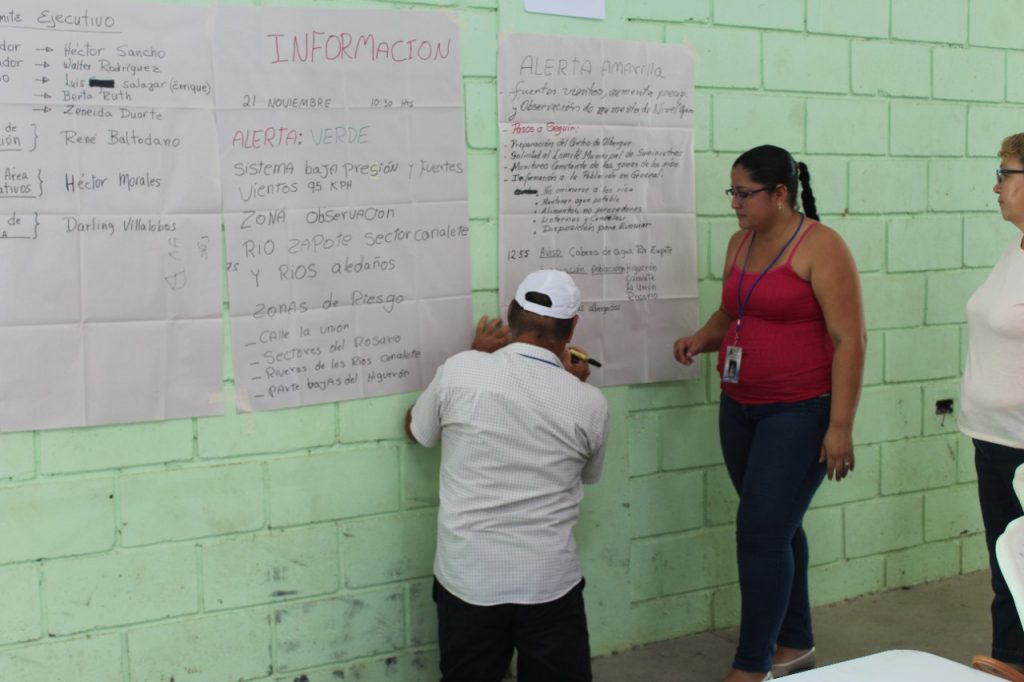

Project leaders emphasize that the equipment is only one component of the SAT-Upala project. The other essential component was more than a year of work to prepare communities. From the beginning, parallel to the acquisition and preparation of equipment, training was carried out with the emergency committees.

Not only was the Municipal Committee trained, but, as part of the project, six new emergency community committees were also formed and trained in Zapote, Pata de Gallo, Bijagua, Canalete, Upala centro and Yolillal, communities located along the Zapote River basin.

Luis Enrique Salazar is a member of the Canalete community emergency committee, one of the committees involved in the SAT project. He says he appreciates the opportunity that communities have been given in risk management, a concept unknown until a couple of years ago.

“We were fortunate to be taken into account for the SAT and it has been a very beneficial experience,” says Luis. “We can say with certainty that we are prepared to face any type of emergency. We have the knowledge, we have the community identified by risk areas, we have a risk map and an emergency plan approved by the CME.”

The other community committees in the basin report similar results. Their capacity has been demonstrated every time that heavy rains cause them to activate their protocols.

“They are already well trained to act in an emergency, according to an established protocol and according to the type of alert we have in the canton, be it green, yellow or red,” said Wilson Espinoza, vice mayor of this border canton.

Teamwork is essential, especially when the rains between June and October cause the rivers to flood.

Laura Pérez Bertozzi, a UNDP consultant and an official of the Department of Risk Management and Community Services at the Red Cross, led an intense day of training for community leaders.

This required first identifying the participants in order to form and structure the committees— then training members on their roles in an emergency, preparing them to deal with hydrological threats, and developing community emergency plans according to the particular needs of each area.

“It was intense and very rewarding work,” says Laura, who worked on the project for a year and three months. “All these people who are now part of a community emergency committee do so on a voluntary basis. We had to prepare them from scratch, since they did not have any type of knowledge in emergencies, but they did have strong past experiences such as Hurricane Otto.”

Each committee even faced a final emergency drill where they were evaluated by the CNE. In addition, they were able to exchange experiences with other community emergency committees in Sarapiquí, who have a similar Early Alert System.

“The six committees maintain fluid communication through a unified WhatsApp chat and radios that are maintained in the upper and lower areas of the basin,” Laura explains. “They are also prepared to handle and analyze the information, which is very important to avoid generating mass panic.”

“If we as a community had been prepared [in 2016] as we are now, we might be telling a different story today. Now we are also thinking of forming a youth brigade to attend to emergencies in the community,” says don Luis Enrique.

Vice Mayor Wilson indicates that, in an emergency, the members of the CCE become authorities of their community.

“They already have a leading role on this issue and do not have to wait for the Municipal Committee to be present to act,” he says.

Coming together

Undoubtedly, the transcendental experience of Hurricane Otto facilitated the immediate mobilization of institutions and organizations willing to make their contribution to the recovery of the canton.

The SAT Upala project has drawn support from institutions such as the National Meteorological Institute, the National Emergency Commission, the Municipality of Upala, the University of Costa Rica, the AyA, the Costa Rican Red Cross, private companies and international organizations such as UNDP, UNHCR, World Vision, USAID and the most recent of them, Fundación Ayuda en Acción.

“Here we are a sum of many institutions that have worked hard to make this system a reality. I believe that we are ready to reach the expected goal of a fully expedited system,” said the vice mayor.

Recently, the IMN, in conjunction with Fundecooperación para el Desarrollo Sostenible, successfully implemented 13 meteorological stations in various cantons of Guanacaste, Puntarenas, Heredia and Alajuela, opening the door to improved emergency response in some of the areas of Costa Rica at greatest risk of flooding.

The most important work must be carried out by the communities themselves, requiring ongoing support from the local governments. They play a fundamental role by responding to requests for aid and training.

Participants in the project assert that the canton of Upala today is better prepared for a serious crisis such as Hurricane Otto.

“Today we do feel that we are more prepared to face an emergency. We know what it is about and how to manage risk from our communities. In addition, we have more resources such as the community hall, which is now in optimal condition to serve as a shelter, for example, ”said Luis Enrique of Canalete.

“I hope that the other cantons of the country do not have to wait for a scenario like Hurricane Otto or Tropical Storm Nate, for example, to be prepared as a population. There is a lot of work that can be done,” says vice mayor Wilson Espinoza.

For her part, Laura Pérez of the Red Cross says that comprehensive programs are available to prepare communities for an emergency. What’s needed for a sustainable SAT project is interest on the part of the community; requests made in a timely manner; and local authorities and communities that fully commit to the project.

An example of this commitment and necessary support is that at this time, the community committees in Upala are continuing to receive virtual training with the support of the Fundación Ayuda en Acción. At the same time, committees are also being formed in other areas of the canton, and being provided with resources such as identification vests to facilitate their work.

The local government also continues to reduce flood risk through mitigation work, although these efforts are limited at present because municipal emergency funds are dedicated COVID-19.

Vice Mayor Wilson Espinoza says that the National Meteorological Institute is now installing a second sensor in the upper part of the basin, near the town of Higuerón and, in the future, plans to install a third lower down, right in the center of Upala. This would reinforce the Early Warning System and further strengthen the project.

On the other hand, the pandemic has introduced new limitations for the effort. Some follow-up trainings for community committees have been suspended, since many of their members do not have a computer or internet access. Similarly, activities such as drills or the formation of other community groups have had to be postponed due to the accelerated increase in COVID-19 cases in the canton.

From informal conversations with my own neighbors and community members, I have been able to observe another limitation to the progress of the project: a lack of knowledge among the population of the canton about the existence of the SAT Upala. This project is a tool that could save the lives of citizens, but many of them do not even know that it exists; others know about the sensor, but do not know how to interpret the data from it.

A population that’s informed and trained about how the sensor works could manage risk simply by entering the link on the IMN website and monitoring the river in real time.

Of course, while information might be lacking, but interest in the subject is not. As Wilson Espinoza points out, the vulnerability of the area is something that every person from Upala is very aware of.

“November 2016 that is still on the minds of many upaleños. We are a vulnerable country; our Municipal Emergency Committee and now our community committees must be prepared for the worst,” the vice mayor concludes. “SAT Upala has become that great ally so that we can avoid experiencing something similar to what happened with Hurricane Otto.”