Third in our April series on rural community tourism in Costa Rica. Read Part One, “The wisdom that comes with a life on the river,” and Part Two, “One step at a time.“

His 52 hectares are home to forest, waterfalls, endemic trees and diverse fauna. Accompanied by the sound of the small stream that crosses the farm, Juan Cubillo guides me to the area where he will place a gutter to hold materials from the river. Little by little, this man, short but with a strong back and arms from a lifetime of digging for gold, he sifts that material until tiny sparkles appear.

In the kitchen of their facilities for tourists, his wife Rosa Montero is preparing an “arepa de orero,” the classic snack that oreros took on their expeditions to extract the coveted metal from the mountain. Don Juan and doña Rosa, formerly gold miners, or oreros, and now hosts of the Gold Tour, lead one of many family enterprises on the Osa Peninsula—a territory in southern Costa Rica where, at dawn, the clouds slip through the exuberant vegetation of the Golfo Dulce Forest Reserve and Corcovado National Park.

There, in and around those mountains that reach to the sea, dozens of people who understand the enormous value of that nature are doing their best to give tourists the most valuable thing that rural community tourism offers: human warmth and knowledge.

However, in addition to preserving the environment, these entrepreneurs have adopted another key component as their daily bread and the key to their success. That’s teamwork and the knowledge that, without adequate promotion of their efforts and offerings, their businesses will not succeed.

This union has proved essential in this region, where natural wealth is a blessing but can also become a limitation. Enoc Espinoza, local leader and owner of Sierpe Azul Exclusive Tours, explains it clearly.

For many years, the Costa Rican government has enacted laws that protect the environment in the Osa Peninsula: “They have done an excellent job because all of us who work on this depend on the environment to be able to carry out our activities,” he says. “It is very important. But the work that should have been done for the human development of the people who protect these lands, has not been taken care of.”

He adds that while laws are restrictive in order to protect the forest, they did not make provisions for the people of the community. Management plans for areas of the Golfo Dulce Forest Reserve allow livestock activity where pastures or agricultural activity already exist, but no finance mechanisms exist to support this activity.

The lack of property titles in forest reserves means that people who have lived there for decades cannot access credit; this legal insecurity generates the constant fear of losing their land at any time, he points out.

That is why rural community tourism has become a hopeful alternative for the inhabitants of the peninsula, a region with great natural wealth that was not previously reflected in the local economy.

Conservation and prosperity hand in hand: Caminos de Osa

Eida Fletes, one of the protagonists of the Heart of Palm (Palmito) Tour in the community of La Palma, tells me how many years ago, when she dreamed of having a tourism project, she went to one of many trainings she’s attended over the years. She told the woman who met with her: “I want my own business, but I’m very poor. I don’t have money.”

The woman, moved, asked her if she knew someone who might lend her a bit of land so she could start her business. To this, doña Eida replied, “’No, no, why do I want a little piece of land? We have a four-hectare property!’ That lady probably wanted to kill me,” she recalls. Now, together with her sister-in-law Yorleni Fletes, she is the owner of Jacana Rey Tours, which offers the Palmito Tour and the Insect Night Tour.

Many of the projects that are now successful in the region previously lacked the empowerment, the entrepreneurial mentality, and the initiative they need to prosper alongside the land they own among the reserves of the Osa Peninsula.

Within this context, Caminos de Osa was born in 2014 with the goal of consolidating a rural community tourism destination that would generate economic growth in local communities. The project followed the path laid out a few years earlier by the Osa and Golfito Initiative (INOGO) of the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment.

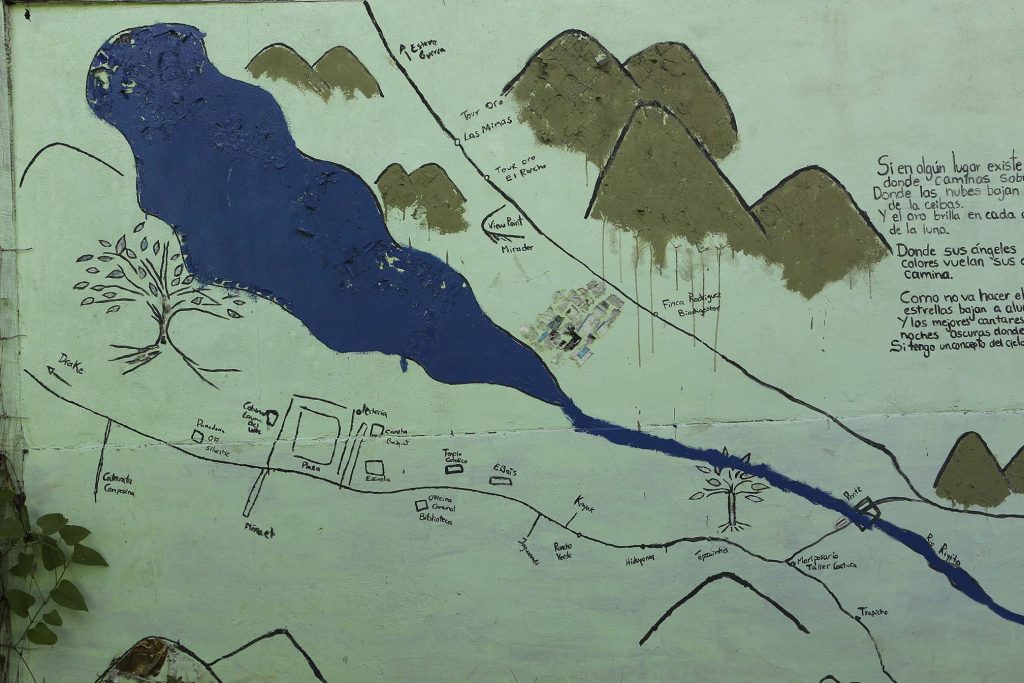

Today, Caminos de Osa offers four routes that link diverse family businesses: accommodation, food, guided tours, thematic attractions and transportation venues. Some sectors of Corcovado National Park are included in the routes: Camino de la Selva (the Forest Trail), Camino del Agua (the Water Trail), Camino del Oro (the Gold Trail), and Osa Elemental.

Over three or four days, the routes allow tourists to visit archaeological sites, indigenous communities, mangroves and jungles. They can participate in horseback riding, night and day walks to see animals, lessons on how the oreros extracted the metal from the mountain, tours of a sugar mill, or, of course, beach lounging.

The project also allows tourists to take one-day tours or design their own route.

“Caminos de Osa arose after years of conservation projects in the Osa Peninsula without significant results in terms of the economic growth of the communities,” explains Ana Camacho; when the project was developed, she was the Strategic Coordinator of on of its supporting institutions, the Costa Rica-United States Foundation (CRUSA). “The reasoning behind Caminos de Osa was that as long as the economic situation of the communities did not improve, the threat to natural resources remained.”

Furthermore, “the Osa Peninsula represented a great irony from every point of view, because—being the jewel in the crown in terms of conservation, with such a high density of biodiversity in such a small area of land—it was impossible to see that the communities didn’t reflect a little of that wealth in economic terms,” Camacho adds. The Osa Peninsula is home to 2.5% of the world’s biodiversity and more than 50% of Costa Rica’s biodiversity, making it one of the regions with the highest density of biological diversity in the world.

Camacho explains that participating communities received extensive training to be able to receive tourism but they were not really part of the chain. Through an assessment conducted with tourism agencies that joined the project (Horizontes Nature Tours, Travel Excellence and Swiss Travel), the project identified existing enterprises in relevant districts. The resulting training strategy was designed to help these enterprises enter the market.

Meanwhile, the travel agencies committed to promoting the Caminos de Osa participants and helping them mature in terms of customer service, infrastructure, administration, and other issues.

The Caminos de Osa project was funded by the CRUSA Foundation and Stanford University, which acted in alliance with the Osa Conservation Area (ACOSA) to then design the routes so that people could travel any of the trails and end at one of the entrances to Corcovado.

These organizations were joined by the firm Reinventing Business for All (RBA), which carried out the necessary market links and identified the skills that entrepreneurs needed in order to meet the requirements of that market.

Change of mentality and local governance

The greatest value of Osa is its people, and that’s why Caminos de Osa is such a solid international product. That’s how Daniel Villafranca, who was the executive director of RBA when the project was developed, puts it in his conversation with El Colectivo 506.

When I visit the enterprises in this area, they prove this beyond a shadow of a doubt.

Johnny Rodríguez and Noemi Quirós are the owners of the Trapiche don Carmen, located in the community of Rancho Quemado, which they proudly present as “the Heart of the Osa.” There, they decided to create an entirely artisanal trapiche, or sugarcane mill, meaning that it produces delicious sugarcane juice with only the help of a horse—or the tourists themselves, since lending a hand is part of the tour.

Sitting with this couple on their balcony—in the heat that’s typical of the area, with a glass of exquisite cane juice and some ripe banana cakes bathed in organic cane honey–is to feel at home, sharing in the warmth of the hosts .

Alvaro Calderón is the owner of Lapamar. This project offers accommodation and kayak tours through the mangroves near La Palma’s Playa Blanca, a beach flanking a calm blue sea. Calderón came to Osa in the 1980s “to hunt, because that was our custom. Then I was looking for gold when I saw a cooperative that made the transaction from oreros to tourism in 1986.”

Don Alvaro began to help a man who worked with tourists and discovered that he loved meeting people from other countries, so he decided to study to become a tour guide. He signed up for English classes and took other courses with the organizations Marviva and Pretoma.

“Today, so many years after I came here to hunt, I don’t kill anything, not even snakes. I don’t even fish,” he tells me. “My life changed. Now, when people want to kill a snake that is not poisonous, I tell them that it is part of the ecosystem.”

Daniel Villafranca explained that it was a difficult and challenging project. “The goal was very ambitious: to transform oreros, hunters, and loggers. To change mental structures, cultural habits. It is a matter of internalization,” he tells me.

“Entrepreneurs were trained on how to create a quality project: marketing, cost structures, insurance, logistics, reservations, payment systems.” He adds that community empowerment was an important component of the process, including work to build trust and constructive relationships.

Villafranca explains that over the course of a year, a program was developed in which people in the Peninsula with tourism knowledge were enlisted as mentors for the entrepreneurs. These mentors had to guide participants to find their own direction, to define their own tourism destination.

Finally, the ventures—some of which did not even have indoor plumbing when they started out—were evaluated by the tourism agencies involved to decide which ones met the necessary requirements to be part of the Caminos or one-day destination offerings. In the end, 35 enterprises successfully completed the entire process.

Another important step was the creation of the Caminos de Osa Association, a local governance figure to represent the opinions of various sectors on tourism issues and promote the sustainable development of the Peninsula. The Association reinvests funds generated through tourism to training, infrastructure, platforms and marketing, among other ends.

From that point on, the project was left in the hands of the community, which was in charge of continuing to establish business relationships with agencies, Villafranca explains.

Prosperity arrives by sea

For Ana Camacho, the success of the entire process “became apparent when the Horizontes agency sold a certain number of Caminos de Osa [experiences] to the National Geographic” Expedition Cruises and Lindblad Expeditions.

Rocío Vargas González is an entrepreneur from the community of La Palma; she opened a soda there 14 years ago, but later decided she’d have to leave the area to increase her income. Otherwise, she could not afford to raise her three children.

However, when she attended training for the Caminos de Osa project, she decided to stay. She began to provide food service at the trainings and, little by little, consolidated ROCA Catering, which offers food, space and equipment for special events.

The hard work and tenacity of this community leader inspired Horizontes Nature Tours to call on her before the arrival of the National Geographic cruise ship to the Osa Peninsula in 2017.

“When the [National Geographic] boat was coming, [Horizontes Director] Patricia Forero told me: ‘We need to rent chairs and tables. I told her that there aren’t any here in the area,” Vargas recalls. Forero proposed that Vargas be the one to provide this service; the Horizontes Foundation granted her a loan to buy chairs, tables and tablecloths. She was able to pay off the loan shortly thereafter.

Since then, doña Rocío has been in charge of feeding the tourists and all the logistics around the cruise: setting up the tables for the tourists’ lunch on the beach, choosing the traditional dance groups that welcome the visitors, and coordinating the vendors of handicrafts that come to offer their products, among other aspects of the visit.

Meanwhile, Alvaro Calderón, from Lapamar, provides his facilities and kayak tours to cruise passengers, as well as food for the guides and the entire team that works with the cruise logistics.

Another beneficiary of this value chain is Enoc Espinoza, owner of Sierpe Azul Exclusive Tours, an entrepreneur who provides the transportation service for cruise tourists to all destinations associated with Caminos de Osa.

Horizontes “managed to bring the National Geographic cruises to Playa Blanca. A cruise ship had never entered here, and they managed to get them there to buy the services associated with Caminos de Osa… this has helped me a lot,” says this entrepreneur from Sierpe who now subcontracts minibus service from others, thereby adding still more beneficiaries to the chain.

Don Enoc also offers kayak tours through the Sierpe-Térraba mangroves, during which tourists have the opportunity to plant a tree.

This achievement can be traced back to 2017, when Horizontes carried out a national and international marketing campaign for Osa’s products and services. With the sponsorship of the CRUSA Foundation and the tour agency’s experience, the Horizontes Foundation was placed in charge of the Caminos de Osa marketing project.

Promotion activities took place in places like the United States (New York, Washington, Seattle, San Francisco), Argentina, Germany and the United Kingdom. The effort eventually led Lindblad Expeditions/Nat Geo to include a visit to the Osa Peninsula in their itineraries.

Between 2017 and November 2019, the impact generated by the visit of the cruise ships was extremely positive, with total income for community members of over $200,000. This allowed Caminos de Osa to provide additional training for guides, local enterprises and the economic value chain in the region.

During this period, the agency brought hundreds, in some cases thousands, of visitors to the businesses that are part of this project with Lindblad Expeditions/Nat Geo: Tour del Palmito, Tour del Oro, Trapiche don Carmen, Lapamar Ecolodge, Catering Roca, Sierpe Azul, Danta Corcovado Lodge, Ficus Tours, and local guides Fernando Guerrero and Elia González.

The power of community unity: The Rancho Quemado Development Association

As I continue to explore the area, I discover that the small community of Rancho Quemado, located in the heart of Osa, is a town of hard-working, authentic people in love with their land. Its inhabitants say they believe in unity, and have managed to prosper together to protect and share with tourists the beauty offered by the mountains that surround them.

The Rancho Quemado Development Association is a success story and an example to follow, according to people who know its history. Members in this association include Caminos de Osa projects such as the Tour del Oro and the Tour del Trapiche, as well as other rural community tourism initiatives powered by their members’ perseverance. que conocen su historia.

At present, the organization operates as the Corazón de Osa Travel Agency, certified by the Costa Rican Tourism Institute (ICT). It recently acquired a minibus that it will use to transport tourists. Among the projects that have been created with the support of this association is the Rancho Quemado Community Biological Monitoring Project, whose 19 participants include Yolanda Rodríguez and Nuria Ureña.

As we walk along the project’s Sensorial Trail, Rodríguez and Ureña tell me that this and other routes were created for wildlife watching walks that help the community generate resources for biological monitoring.

“El Sensorial was created to give an opportunity to people with some type of disability, since it is accessible in the community,” explains Rodríguez. “It is very central, but at the same time it is surrounded by forest, and a huge wealth of fauna visits this place.”

In addition to the Sensorial Trail, the Osa Trail, the Laguna Chocuaco viewing platform, and the Tángara Hormiguera platform, all offer different vantage points to observe diverse species.

“On the daytime tours we can find large birds such as peacocks, wild chickens, toucans, many migratory birds, mammals,” says Rodríguez, adding that jaguar, puma, manigordo, caucel and jaguarundi have been registered in the camera traps… and “arduous community work has allowed the increase in the population of wild pigs.”

These women have cultivated their extensive knowledge of flora and fauna since 2015, when they both took on the mission of working in support of biological monitoring. That year, residents of Rancho Quemado were trained in monitoring for 12 months by the National Parks System (SINAC), ACOSA, and the nonprofit Aves de Osa.

Now, Yolanda Rodríguez and Nuria Ureña are sharing their extensive knowledge with members of the communities of Bahía Chal, Alto San Juan and San Juan de Sierpe, all close to the Luis Jorge Poveda Alvarez Arboretum, a forest conservation project located in Bahía Chal.

In a six-month training that began in March, they are teaching participants to count birds in the Arboretum but also in their own communities, in order to determine the biodiversity of their area.

After the theory class, at about 10:20 am, we walk towards the entrance of the Arboretum and spot a king vulture in mid-flight. The intense sun beats down on us, but as we take just a few steps into the Arboretum, the shock of the intense heat lessens. The intense sun beats down on us, but as we take just a few steps into the Arboretum, the shock of the intense heat lessens.

There, during a short tour, my hosts explain the tools they use for monitoring, as they were identifying—by sight or by ear—the birds that we encounter along the way. With a wide command of the subject, both guides mention the common and scientific names of the species, sometimes just by listening to their song.

In just over two hours, between 10:20 am and 12:40 pm, they manage to count 33 species in hours when bird movement and sightings are comparatively low.

The Arboretum project aims to increase knowledge and awareness about forest conservation in the communities of Bahía Chal, Alto San Juan and San Juan de Sierpe, which register high volumes of complaints about illegal logging and extraction of flora and fauna.

Monitoring in the Arboretum is part of the First Debt for Nature Swap, where the Horizontes Foundation participates as the executing entity, explains Florencia Lathrop, logistics coordinator in the area.

In addition, residents of the three towns have already formed an association and are eager to work to make the Arboretum a place of protection and teaching.

Lilliam Nieto is an enthusiastic 18-year-old who sits on the association’s board. Lilliam has participated in the Arboretum project since she was 10 years old and now dreams that the Arboretum will one day be a place where children and young people can exploit their potential, a program led by the three communities “but with fellowship across the Osa Peninsula.” She dreams it, but above all, she works for this goal.

Jeaustin Durán, a shy 19-year-old, approached the Arboretum out of curiosity when he was about 14 years old, but is now aware of the importance of caring for the trees. In the future, Jeaustin says he would like more members of his community, San Juan de Sierpe, to join the project.

“Most of them are loggers. When there is a reforestation project they don’t like it; for them it is a bad thing,” he tells me. “It is necessary to try to change the mentality so that everyone begins to see that you’re not doing anything wrong–we’re looking for a benefit for all.”

The basis of success: knowledge, professionalism and perseverance

Yorleni Fletes, one of the owners of Jacana Rey Tours, was always a “very shy girl. Not anymore,” says her sister-in-law Eida Fletes, who attributes Yorleni’s development to the trainings in which she participated.

Yorleni explains that she received trainings from the Neotrópica Foundation, the University of Costa Rica, the State Distance University (UNED) and Marviva, among others. Topics included how to speak to the public, how to explain your project, customer service, marketing and accounting.

Now, she guides tourists through the palms. She explains how to cut them while protecting their soft hearts, which she finally shows off.

All the entrepreneurs mention institutions such as those mentioned by Fletes and describe how trainings helped them learn how to manage their finances, serve their customers, and how to improve their facilities.

Rocío Vargas, in charge of logistics for National Geographic cruise visits, says that the training she received in the Caminos de Osa process changed her life.

“The first day, I fell in love with the training. There was a psychologist—I always talk about her because she is amazing, Cinthia—she started to make a change in me,” she explains.

The orero Juan Cubillo also experienced a great change driven by his wife Rosa Montero, who saw the benefits of protecting nature on their farm in Rancho Quemado. Montero presented a project and won, in a field of some 50 proposals, a two-year training that would provide the necessary tools to start their enterprise.

At first, her husband was not so sure because “I was something else. I was a hunter, a predator, a mountain destroyer,” he says, adding that at some point in the process he felt that he had received many trainings but “the fruit was not being seen.” This changed when Caminos de Osa arrived and, later, the Horizontes agency and the National Geographic cruises.

The Caminos de Osa product prompted 35 enterprises to enter the market and achieve a necessary chain for rural community tourism projects to generate income for their owners.

The challenge of initiatives like these is to last. According to Daniel Villafranca, it takes five to seven years of financing and work to consolidate a project like this.

Of course, just before Caminos de Osa reached its seven-year mark, something rather unusual took place: the global challenge posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, which for months stopped tourism altogether.

The entrepreneurs we visit are positive, however, saying they are confident that the pandemic will pass, tourism will return, and, little by little, they will revive their enterprises.

When we ask exactly how many entrepreneurs are still a part of Caminos de Osa today, the responses are filled with uncertainty. The secretary of the Board of Directors of the Caminos de Osa Association, Susana Matamoros, affirms that some projects may have closed because the families left the area.

It’s also possible that some entrepreneurs do not appear on the project’s website because they may not have applied for, or completed, a quality seal that the association created to evaluate quality and service.

Matamoros says that during the pandemic, everyone closed their doors, but only temporarily. Now, they are recovering, but “the little tourism that has arrived goes to Corcovado.”

She says that the association has a person who works a few hours a week to keep its website current, but to sell the Caminos, they need to hire staff, and don’t have the economic capacity to do so at present.

Logistics are complicated. Careful coordination is needed, and many entrepreneurs, especially those who are located in very remote places or in the mountains, do not have email, internet or, in some cases, telephone signal, she points out.

Matamoros adds that in the last assembly, held before the pandemic, participation was very low.

“Culturally, in Osa there is a situation: some people, if they are not given transportation and food, do not arrive” for meetings, she says. “Some live in remote areas where there is no bus service and it is difficult for them to get there.”

The Regional Development Board of the South Zone (Judesur) is developing a project to support the association so that it can acquire a civil liability policy for tourists, build an office. and to improve its website. However, the Association is still waiting for these funds, according to Matamoros.

Despite the lack of funds caused by the lack of tourism over the last year, Matamoros says she hopes to conduct an update in April to verify how many projects are still active in the project.

The entrepreneurs who opened their doors to us say that Caminos de Osa is a valuable project that educated them and launched them into the market.

Their greatest lesson? According to Enoc Espinoza, it was that projects often work better “when one joins other people to achieve a goal.”

Rural community tourism in the Osa Peninsula faces the challenge of continuing this unity in order to achieve lasting sustainability, and continue to protect the biodiversity that this territory contains. The challenge for the rest of us? To continue to visit them.

Learn more about Caminos de Osa, Horizontes Nature Tours, and the Horizontes Foundation. You can support various of the organizations mentioned in this story through Amigos of Costa Rica, which receives U.S. tax-deductible donations on behalf of Costa Rican nonprofits: Caminos de Osa, the Asociación de Desarrollo Integral de Rancho Quemado, and the Horizontes Foundation. We thank the Horizontes Foundation for supporting our reporting by covering travel and tour costs for El Colectivo 506 during our unforgettable visit to Osa.