In September 2020, the Costa Rican Social Security Fund, or Caja (CCSS), reported that— according to statistical data from the Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN)—one in 52 people in Costa Rica will be diagnosed with cancer, and one in 117 will die from the disease.

Today is October 1st, a day when many Costa Ricans will begin to think about cancer, particularly breast cancer, for a month. However, the statistic above tells us that it is something that should be kept in mind throughout the year.

“Eighteen years ago in Costa Rica, using the word cancer was taboo. Nobody said it,” says Fabiola G. Ross, one of the founders and, until a year ago, executive director of the Anna Ross Foundation. “You couldn’t get invited to talk about cancer on television programs because that wasn’t nice to talk about in the morning.”

Awareness and recognition of cancer as a public health problem has improved a lot in the last 18 years, but cancer rates have not. According to data from the INEC and the Public Helath Ministry’s National Registry of Tumors, cancer is the second most significant cause of death in Costa Rica, responsible for approximately 5,000 deaths per year.

“We are at a time where the Costa Rican reality has changed a lot,” says Fabiola. “When the CCSS started 80 years ago, we were a country where people died of diarrhea. Today, we have one of the highest life expectancies in the world.”

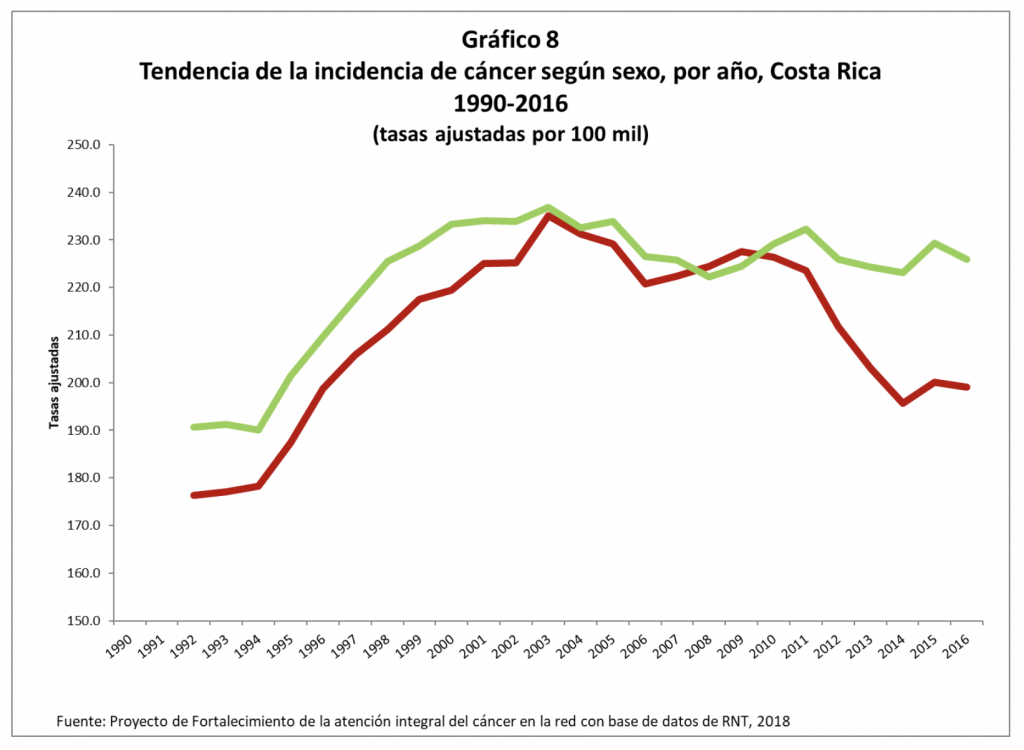

Although a statistical analysis by the Strengthening Comprehensive Cancer Care project from the CCSS, shows that the number of new cases has decreased slightly since 1990, the country still registered 11,350 new diagnoses in 2016, the last year with official data.

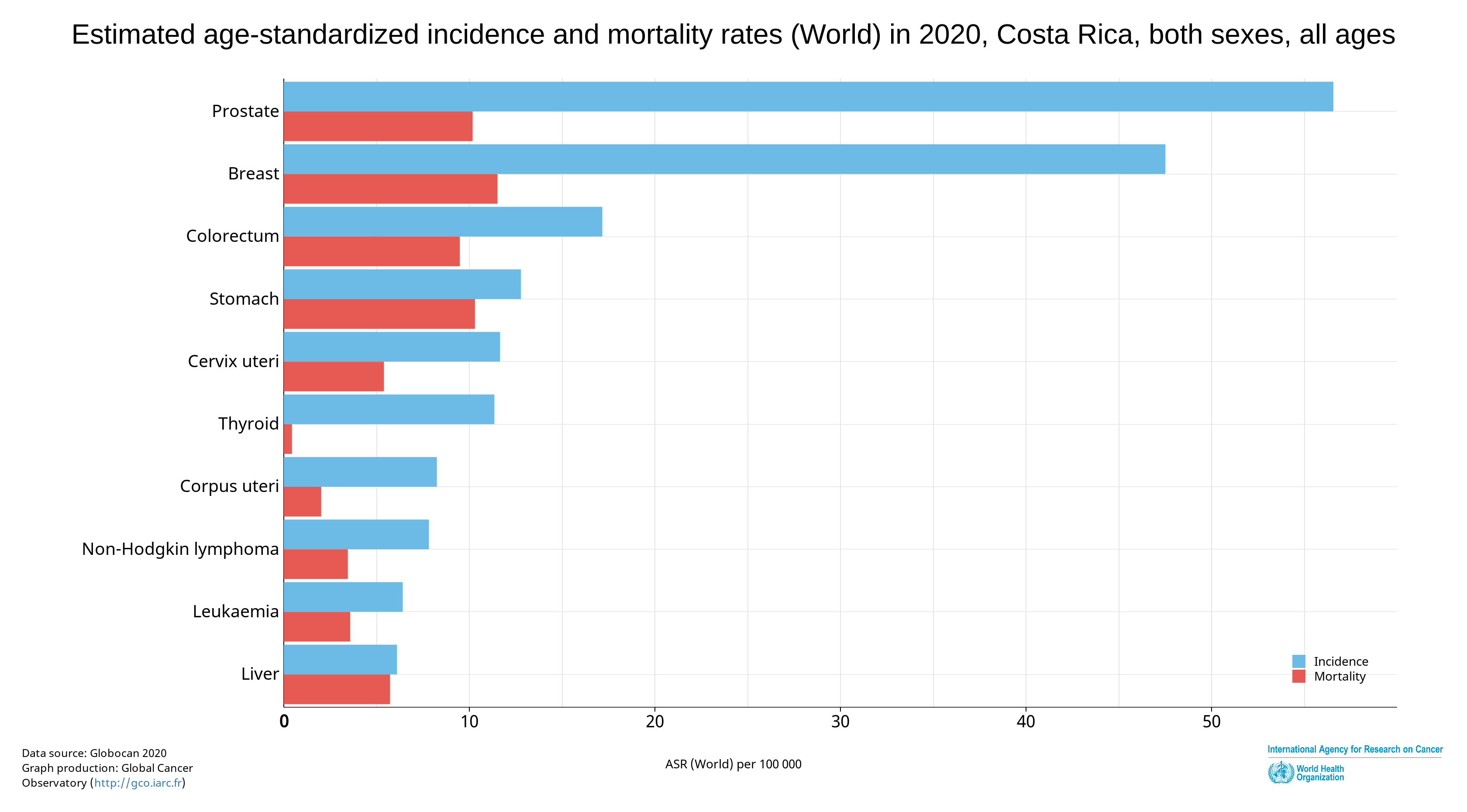

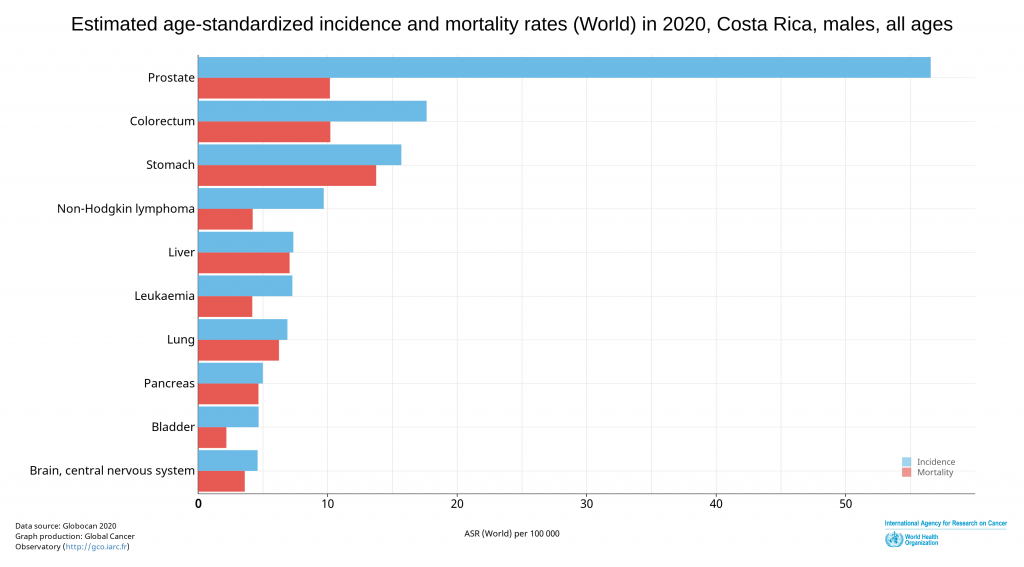

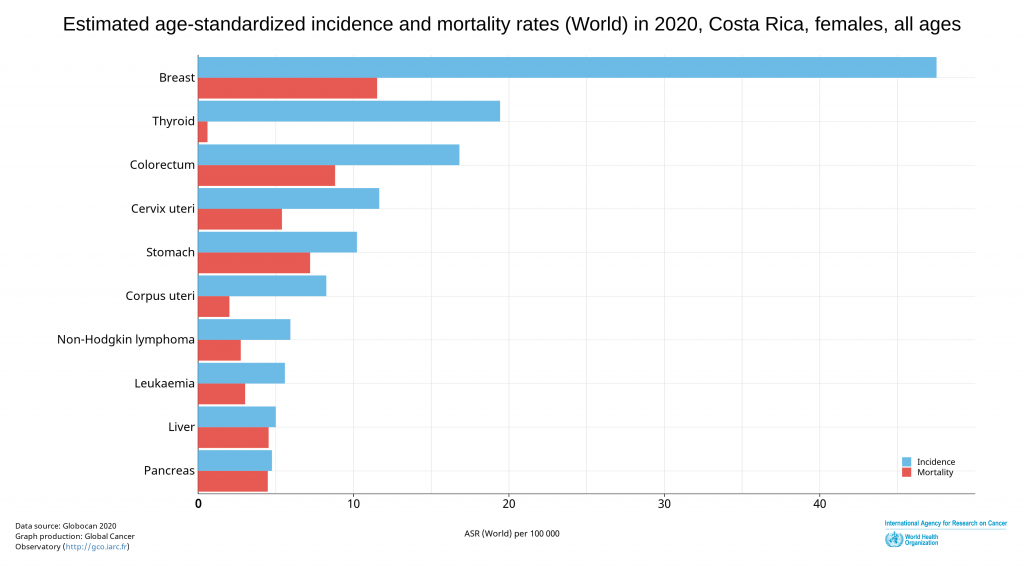

The most common cancer among Costa Ricans is prostate cancer, followed by breast cancer, both with low mortality rates. Stomach cancer and colorectal cancer come next on the list, but they are the cancers with the highest weight in mortality statistics.

“Cancer is a genetic disease,” says Dr. Alejandro Calderón, of the Caja’s Strengthening Comprehensive Cancer Care project. It’s important to clarify this comment: only 10% of cancer cases are transmitted through genes from parents to children. The genetics that Dr. Alejandro is talking about is the “accumulation of alterations in the DNA of each person that end up altering their normality.”

What does he mean by “alterations”? What causes them?

So… why do we get cancer?

According to the World Health Organization, a third of cancer cases in the world can be prevented by making changes in people’s lifestyles, such as quitting smoking, healthy eating, and physical activity.

That is, the impact of the alterations in our body that can cause cancer depend on how healthy our daily habits are, on environmental factors such as high exposure to the sun, or on not being vaccinated against viruses that can cause cancer, such as that of hepatitis or human papilloma.

Dr. Alejandro points out that there is one risk factor that is impossible to avoid and that inevitably favors the development of these alterations in our genetics.

“The older we are, the greater the possibilities of this type of micromutations, which, as they accumulate, can cause these diseases,” he says. In general, the incidence of cancer in humans increases after 45 years of age.

Costa Rica is a country whose population pyramid has already been inverted: that is, we have more and more elderly people and fewer people under 15 years of age. This trend is not going to change. That’s why Costa Rica must reduce its risk factors related to lifestyle habits if it’s going to reduce the impact of cancer on our population, since our population will inevitably have higher cancer rates just because of aging.

Dr. Maureen Fonseca, coordinator of the Caja’s breast clinics, explains that reducing risk factors is something that can be achieved with small and gradual changes that help prevent all types of cancer.

“Healthy eating consists of adequate portions for each person; reducing the consumption of sugar and unsaturated and trans fats, as well as ‘junk’ food; and consuming water to stay hydrated,” says Dr. Maureen. She also emphasizes the importance of physical activity, as simple as walking; the gradual reduction of tobacco use; maintaining a healthy weight; and paying attention to our mental health.

“[Poor] mental health can cause us tremendous chaos,” she says, “right down to: ‘I have not done the [screening] study because I am afraid that they will tell me I have cancer.’

“When you talk about cancer, you talk about the disease,” says Dr. Maureen. “We have to turn it around and focus on prevention, before we get to the disease.”

The challenges posed by cancer in Costa Rica are complex, and require that we talk about prevention as much as, or more than, we talk about care. However, when prevention has not been enough, early detection is key.

“If we have already exposed ourselves to risk factors and those factors could generate an alteration, what we must do is detect them early,” adds Dr. Alejandro. “Screening programs are essential.”

What is early detection?

“Another third [of cancer cases] can be detected early, increasing the chances of survival,” adds Dr. Alejandro. “The survival rates for colorectal, breast, and cervical cancer in this country are the highest in Latin America. That means we are doing something right when it comes to early detection programs. There is a long way to go, but what we do has had a positive impact.”

“Early detection remains the queen of beating cancer,” says Fabiola, of the Anna Ross Foundation.

Early detection of cancer depends on screening. Dr. Maureen explains that “screening is a study that can be applied with relative ease to the general population without restrictions,” and that its results make it possible to determine whether to continue with other more specialized studies to diagnose whether that person has cancer. For each type of cancer, there is a specific type of screening or study that can trigger follow-ups if a potential problem is detected.

“Screening (tamizaje) is done in asymptomatic patients: what you are looking for is an early diagnosis,” explains Dr. Efraín Cambronero, an oncological surgeon who practices in the private sector, contrasting screening and diagnosis. “A diagnostic mammogram is when you feel a lump.”

For Dr. Efraín, screening “has its flaws. It is not perfect.” He says that if screening is not performed in the relevant age group, overdiagnosis may occur, generating false positives. However, he agrees with the CCSS physicians interviewed that screening applied to the populations most at risk of developing cancer is the best way to reduce cancer mortality.

“Screening programs are a shared responsibility: first, we as a health system have to offer it, and second, each person has the responsibility to show up,” adds Dr. Alejandro. “We need to educate people so they can know the importance of taking these tests.”

Cancer and COVID

In an ideal scenario, Costa Rica would implement population screening programs in which all population segments that need preventive cancer control undergo organized and systematic screenings. While all people who contribute to Social Security have the right to undergo these early detection tests, there is still no national system in Costa Rica that controls these screenings.

Since 2017, several pilot screening plans have been implemented: in these pilots, where specific screening studies are applied to selected communities, a system has been established that controls the frequency of the screenings and invites the community to participate. In 2019, many of these organized screenings entered their second round of analysis.

Then the pandemic arrived.

Dr. Alejandro explains that the Caja expects that COVID-19 will increase cancer rates in Costa Rica for three reasons. First, confinement and isolation may have made people more sedentary and increased their unhealthy lifestyle habits. Second, early detection programs have not only slowed down, but because “during the climax [of COVID], there was a moment when face-to-face consultations were suspended and we began to attend patients virtually.” This directly affected the application of exams and studies that can only be done in person.

“In the first half of 2020, we decreased the number of pap smears compared to 2019 by 40%,” he says. “There are many people [who haven’t had that screening] and who knows how many cases [of suspected cancer] are not being detected.”

Finally, while the Caja has worked to avoid this, it’s clear that some people already diagnosed with cancer may “have had delays in their care or are decompensated,” he says. However, he adds that “the most significant impact we are going to have is in terms of early detection.”

In the coming weeks, El Colectivo 506 will focus its magnifying glass on early detection programs for breast cancer, prostate cancer, colorectal cancer and cervical cancer—not only to show what those screening processes looked like through March 2020, and the impact that COVID has had since then, but also to share information about how each Costa Rican can, and should, participate in these programs.