It all started when Betsy López ran out of money for diapers.

Her baby, Dereck, now two and a half, needed a diaper change, and she was empty-handed. Times were tough for her family of four in the Guanacaste coastal town of Nosara: she’d taken a step back from her work in the tourism industry to have her second child, and her husband was laid off because of the COVID-19 pandemic. When she looked around online for less expensive ways to keep Dereck in diapers, she learned cloth diapers—more economical, better for planet, no local manufacturers that she could find in her area—and the stars aligned.

“When I saw how great the product was, that you could wash it and this would help you save money… I had a vision,” she says, explaining how she by purchasing cloth diapers to sell before she quickly moved on to making her own. Eco Baby Nosara was born. In hopes of creating a workshop with additional machines so she could employ other women, she turned to bank offices in the area for a small business loan.

It didn’t go well.

She says that at the Banco Nacional, she was turned away immediately because her business was less than two years old. At the Banco de Costa Rica, she began a year-long process of paperwork that ultimately resulted in rejection.

Her story of frustration and ultimate success has something in common with what other entrepreneurs, bank officials, and business advisors have told El Colectivo 506 this month as part of “Toolkit 2022.” Their comments have painted a portrait of a small business financing system with great potential and significant resources, but also missed opportunities. From our perspective, it looks like a chain with lots of broken links.

What’s the truth behind a story like Betsy’s? What are the real problems with small business financing in Costa Rica, and what are misconceptions? And why do so many entrepreneurs say microcredit is impossible to obtain in a country with a well-funded banking system set up for exactly that purpose?

Victor Acosta of Banco Nacional has spent decades working in small business finance, and has seen various iterations of microcredit programs, starting with the BN Desarrollo program, launched in 1999. Through a 2008 law, Costa Rica established Sistema de Banca para el Desarrollo (SBD), or Development Banking System, designed to support the growth of micro, small and medium businesses in Costa Rica.

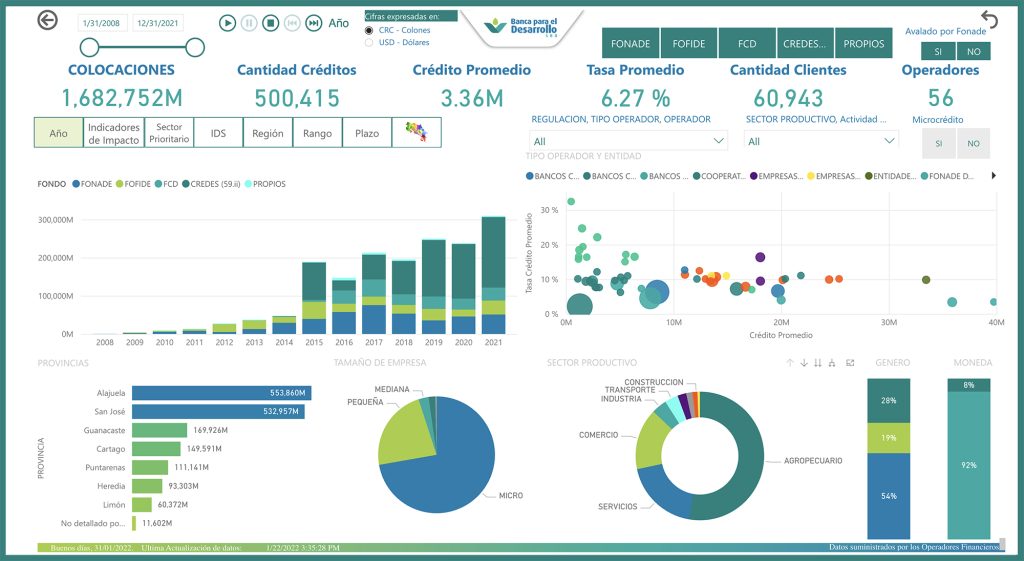

The System, which is run by a Technical Secretariat as a decentralized public institution, uses funds from three sources. The National Development Fund, or FONADE, is funded by public budgets and trusts. The Development Finance Fund (FOFIDE) is made up of 5% of the annual net utilities of public banks, and are administered by each bank.

The third source of funding, and the largest, is the Development Credit Fund, or FCD. It’s funded 17% of all private banks’ savings deposits; these are administered half and half by public banks, Banco Nacional and Banco de Costa Rica, Victor explains.

From Jan. 31, 2008, through Dec. 31, 2021, the SBD has placed approximately 1.68 trillion colones, or $2.95 billion, in credits through financial operators (with 40 listed on the System’s website at present, and new operators and credit lines being created on a rolling basis).

The System also offers a wide range of non-financial instruments to support PYMES: namely, trainings, which they coordinate through a partnership with the National Training Institute (INA) and other entities.

The system is designed to circumvent requirements designed for larger businesses and to drastically increase the access of PYMES to credit and other resources.

So, is it working?

How it’s going

Betsy, and many of the participants in our Entrepreneurs 506 group, say the answer is no. Or, at the very least, the system needs major improvements so that financing options can be easier to understand and navigate, and overworked business owners can avoid sinking months or even years into processes that will lead to rejection.

In Betsy’s case, she says that she dove into the series of requirements put before her by bank analysts pretty eagerly—and while the processes did teach her useful lessons about managing her expenses and income, some of the information required just didn’t make sense for her brand-new enterprise.

“They asked me for so many documents and studies: a marketing study, a detailed cash flow study, things and concepts that I’d never heard of that I learned about there. It was good for that!” she says, laughing. She had “to do a projection of the project in the future… with real numbers… but diay, at the same time it wasn’t real, because I hadn’t even opened the workshop. I hadn’t opened a store. I had no idea how much I’d sell in a day, and I had to put down on paper how much I’d sell in a day.”

Ultimately, the exercise showed that she’d need 3-4 million colones (approximately $4,700-6,000) to create her workshop. After a full year of working through the process, she was told that her application had been rejected.

“I said fine, that doesn’t matter, give me less,” she says. “The bank said no, it couldn’t do that, because the study that had been done was for 3-4 million.”

Only when she found a local fund called Nosara Crece was she able to get the support that has allowed Eco Baby Nosara to grow and expand. The fund provided her with 1.2 million colones (just under $1,900) with a monthly payment of 100,000 colones ($156), that allowed her to by an industrial sewing machine and imported fabric to make her products. While her dream of outfitting a full workshop and providing other women with jobs are still in the future, this smaller loan got her business going. Today, she ships disposable diapers all over Costa Rica, supplies the Super Nosara La Paloma market, and sells her reusable sanitary pads to Harmony Hotel in Nosara, which provides them to its guests.

Fund director Emmanuel Gutiérrez says that one reason for the disconnect between SBD operators and rural entrepreneurs is the simple fact that rural businesses’ cash flow is often so low by urban standards, and often wavers drastically between the high and low tourism seasons.

“An enterprise’s cash flow is variable,” he explains: it might be $3,000 per month in the high season, $500 in the low. “When a San José banker sees those numbers, his hair stands on end.”

How does a banker respond? Victor says that to some degree, the SBD gets a bad rap because “there’s a lot of misinformation about these issues, taboos, urban legends.” Since each operator’s requirements are different, entrepreneurs might be given information in one location or institution and repeat it to other entrepreneurs as a blanket, nationwide requirement.

At the same time, he points to something mentioned by other interviewees as well: the varied results an entrepreneur might obtain depending on who’s receiving the loan application. Of course, each financial operator’s requirements vary, and this can be confusing for entrepreneurs—and can lead someone rejected by one institution to assume he or she would be rejected by all of them. However, results can also vary from one individual financial analyst to another. After all, the decision about whether to grant a loan is not only subject to concrete requirements, but also to an analyst’s opinion. (One possible example is right in Betsy’s story: you might remember that she says a Banco Nacional analyst in Nosara told her she couldn’t get a loan until her business was two years old, while Victor says the Banco Nacional does not require this.)

“The executive in charge has an effect, of course, like everything else. We’re people,” he says, adding that operators like Banco Nacional are also constantly trying to improve. When asked whether the bank ever receives entrepreneurs that have had bad experiences with other operators, he says that this does happen—but that “that bad experience might even have been with us, eight years ago, because we’ve been incorporating improvements.”

He mentions the case of a Desamparados shoemaker who was originally turned down by Banco Nacional, but went on to become one of the first recipients of the bank’s PYME Fácil loans.

What kinds of improvements can operators, or the System as a whole, implement?

Herramientas para emprendedores y viajeros: certificaciones para pequeñas empresas en Costa Rica

Potential solutions

Our interviews (which have not yet included representatives from the SBD; they did not respond to interview requests by our publication date) point to a number of potential solutions to entrepreneur-System gaps that are either in place, being developed, or being discussed as steps that should be taken.

Victor points to the Rural Support Councils implemented by the Banco Nacional as one success story: because rural entrepreneurs so often struggle to show their capacity for repayment or collateral, these councils united local leaders from Integral Development Associations (ADIs), water councils or ASADAS, and local chambers who can vouch for area residents.

A similar approach is opening more credit lines that are actually operated by local entities, a step that Nosara Crece has pursued. According to Emmanuel that having operators who are a part of the local community, know the people involved, and have a specific mission to achieve small business growth—rather than traditional financial institutions that must ensure they are pursuing financial returns—is absolutely key if Costa RIca is going to break down barriers to small business financing.

He says that Nosara Crece, which grew out of a training program called Viva el Sueño, has been successful because it knows how to “pamper the beneficiary.” He adds that he’s seen far too many entrepreneurs encouraged by financial operators to opt for a personal loan with a 55% annual rate, or even to resort to usurious lenders.

“When we’d tell people our rate was 20%, people would ask us, ‘Is that annual, or monthly?’” he says, referring to his annual rate. “For me, that was really shocking.”

Nosara Crece is now working to raise funds to continue growing. Among its goals are a priority also mentioned by Victor at Banco Nacional, and many of the SBD’s critics during its years of operation: the need for a higher proportion of seed funding. If more businesses can access small amounts of non-reimbursable funding, the system will be quicker and more effective, they say.

A final idea is both simple and complex: training and encouraging the people who receive entrepreneurs who are soliciting loans so that, if the entrepreneur is not a good fit for that financial operator, they can be guided towards a better solution.

“We need more knowledge interaction,” says Victor, reflecting on his 22-plus years working to support PYMES at the Banco Nacional. “Each one of us who participates in this context of entrepreneurship and development promotion should clearly understand where a person should go who has a certain need.”

“There’s a lack of empathy, and there’s a lack of collaboration within the ecosystem,” says Patricia Umaña Porras, head of PYME services, including SBD loans, at the Coocique cooperative in Ciudad Quesada, Alajuela. “I think that as part of the monthly revisions the SBD performs on us [as financial operators], they should… ask the operator: Well, what are you doing to promote financial inclusion? How do you ensure that your entire platform of collaborators knows what can and can’t be done?”

She adds that while the SBD trains one contact person per operator, this training should be expanded to all the people who interact with entrepreneurs.

Betsy, who says she’s proud to have fought on with Eco Baby Nosara, believes that Costa Rica will win if the system becomes more inclusive.

“I do think it would be good for banks to give people like me a chance,” she says. “To help people who want to get ahead, who are fighters, and maybe have nothing to give the bank to back them up.”

Read the final story of our January edition, full of advice for entrepreneurs who want to navigate Costa Rica’s small business financing system for the first time. And follow our Entrepreneurs 506 vertical and WhatsApp community throughout 2022 for more conversation and journalism about entrepreneurs. Comments? Write us at 8506.1506.