Short answer:yes. Many of the indigenous territories of Costa Rica offer tourist services and activities, some for more than 30 years.

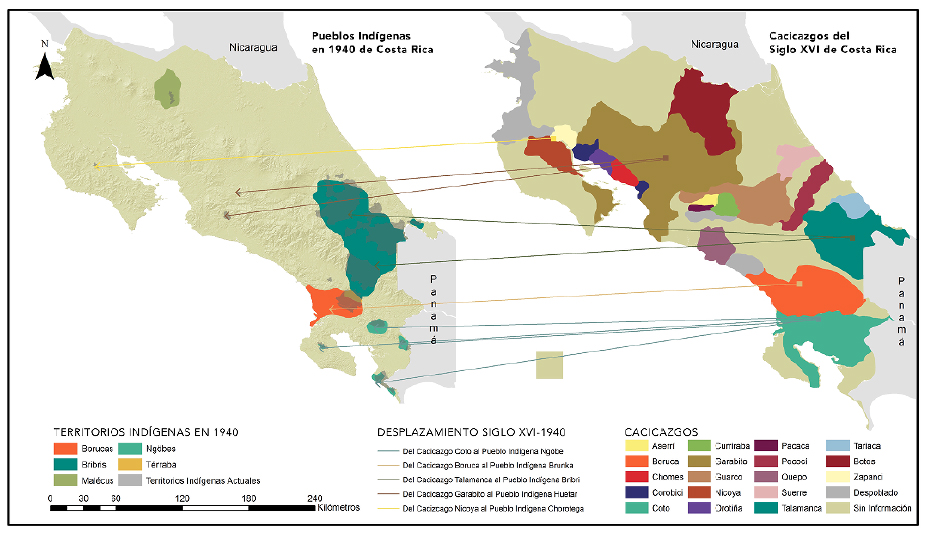

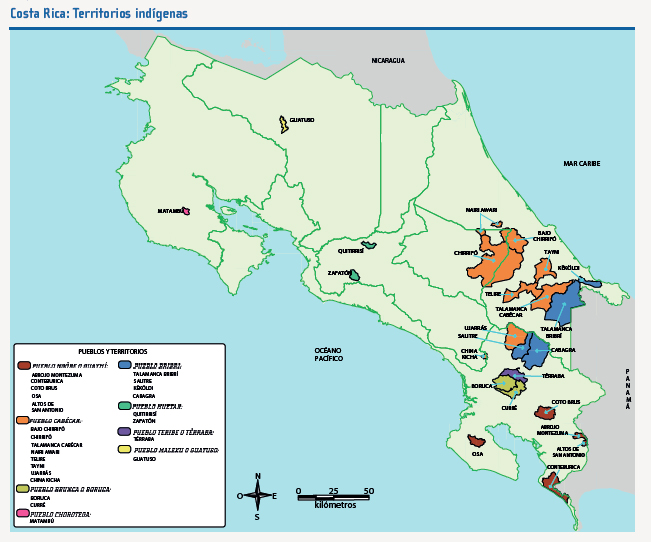

In Costa Rica, according to the 2011 census by the National Institute of Statistics and Census (INEC), more than 104,000 people identify themselves as indigenous— that is, 2.4% of Costa Ricans. Of these, 75% identify themselves as part of one of eight indigenous groups, some of which have two different names—Bribri, Brunca or Boruca, Cabécar, Chorotega, Huetar, Maleku or Guatuso, Ngöbe or Guaymí, Teribe or Térraba—and live in one of the country’s 24 indigenous territories. Those territories correspond to 6.7% of Costa Rica. It should be noted that a large amount of that territory is still in the hands of non-indigenous people, causing ongoing conflicts.

In the coming weeks, in the Travel and Living section of El Colectivo 506, we’ll be sharing information about various options for travelers who want to meet, share and support the indigenous communities of Costa Rica. But first, here’s some general information about the reality of these communities and the impact that tourism has had on their lives.

Recognition of indigenous peoples in Costa Rica

In the 1980s and early 1990s, many Costa Ricans experienced a change in the way we were taught about our indigenous peoples. What I experienced in my school was a clear example. First, they told us that when the Spaniards arrived in Costa Rica, there were just a few indigenous people here and there, lost in the “jungle,” eager to receive any visitor. Less than two years later, we were hosting debates challenging that position.

However, although 30 years have passed since that change, Costa Rica continues to debate the importance of native peoples in our past, present and future.

Land ownership is one of the biggest problems faced by the indigenous population of Costa Rica. Although the limits of these territories were established in 1977, there are many non-indigenous people who continue to use these lands and refuse to hand them over to their legal owners. Much has been reported about the violence that has been generated as indigenous peoples try to recover their territory, largely unaided by a government that has been unable to enforce the law.

These indigenous territories do not belong to a person or a family. Rather, they belong collectively to each of these indigenous communities. Therefore, they are not territories that can be sold, transferred, or given to third parties.

Another reality that native peoples experience is dire poverty. According to the report “The Indigenous World 2021: Costa Rica,”in a country where about 20% of the population lives below the poverty line, this percentage reaches alarming heights among the indigenous: Cabécar 94.3%; Ngäbe 87.0%; Broran 85.0%; Bribri 70.8%; Brunka 60.7%; Maleku 44.3%; Chorotega 35.5% and Huetar 34.2%.”

Despite these difficulties, Costa Rica’s indigenous peoples are increasingly well-organized. The Indigenous World report describes organizations that are recognized not only by the government, but also by the peoples themselves: the National Indigenous Roundtable of Costa Rica (MNICR), the National Front of Indigenous Peoples (FRENAPI), the Bribri-Cabécar Indigenous Network (RIBCA), the Pacific Ngäbe Association, the Dikes Aboriginal Regional Association (ARADIKES), the National Forum of Indigenous Women, and the Interuniversity Indigenous Movement.

The tourist activities and services that have been developed in indigenous territories have helped strengthen that organizational capacity and the defense of these cultures.

Tourism and the indigenous peoples of Costa Rica

“Both domestic and international tourists have something in common, and that is that they do not know about the Costa Rican indigenous reality, because it is not something that is constantly taught,” says Jorge Cole. He’s an anthropologist who has worked with indigenous peoples from organizations such as The Nature Conservancy, MarViva Foundation, and the Alternative and Rural Tourism Conservation Community Association (ACTUAR), and also as a consultant for instances such as IUCN and UNDP.

However, the expert says that going unnoticed has allowed these communities to create offerings of services and tourist attractions in a more organic and autonomous way.

“The positive thing is that there are no realities that exist in other countries, where tourism sometimes uses the indigenous theme,” he explains, referring to situations where non-indigenous people offer services or products that appropriate the characteristics of the culture. Some might even offer activities in indigenous territory and communities that leave very little economic and social benefit for the community. “In Costa Rica, there are good practices, but there is a challenge. The institutional framework has not yet properly supported the issue of cultural tourism. It is a segment [of Costa Rica’s tourist offerings] that is not fully positioned in the country. The indigenous territories would play a very important role in this consolidation.”

According to Jorge, the main limitation faced by the tourism initiatives of indigenous peoples in Costa Rica is the lack of institutional support, especially when they try to apply for credits that allow them to invest and grow: “Due to an issue of land ownership, which are collective, the national credit system does not take into account the particularities of the indigenous territories, and these people cannot take out loans.”

He says that as a result, the achievements of these communities are the result of their own efforts and the support they receive from international cooperation or non-governmental organizations. That’s why the future of tourism in these territories will depend on the organizational capacity of the peoples themselves.

“When it is participatory and the community is included, it is the people themselves who must choose what they want to share and how to share it,” says Jorge. “The future of tourism is that all the territories make participatory regulations on how they want to offer tourism.”

Jorge also points to the importance of generating more public-private alliances and support from the state that strengthen tourism ventures surrounding specific destinations. Jorge explains that, for example, the five indigenous territories of Buenos Aires in Puntarenas all have tourist offerings, so this should be promoted as a destination.

Why should tourists visit an indigenous community in Costa Rica?

“There is a benefit of interculturality that is learning from the language, the worldview, the gastronomy, and various elements of the groups,” says Jorge. “It is educational tourism.”

What’s more, tourists who decide to include a service or activity within an indigenous territory in their visits to Costa Rica will also have the satisfaction of knowing that their tourist dollars will have a positive impact.

“Tourism in indigenous territories is being developed by organized groups or networks, so [tourism] strengthens the organization,” says Jorge. “It builds more local capacities in topics such as food handling and tourism guidance.” He adds that tourism has also helped some indigenous groups recover some of their cultural experiences and incorporate them into their offerings, such as gastronomy and special celebrations.

In turn, the tourists will be not only helping to reduce inequality and the gaps that separate these indigenous groups from the rest of Costa Rica, but also contributing to gender equality. Many of these initiatives have been founded and led by women who, according to the expert, seek “alternative forms of income consistent with their cultural activities.”

“It is a culturally and socially responsible tourism”, concludes Jorge.

Tourism in indigenous communities in Costa Rica: Térraba and Bribri

Tourism in indigenous communities in Costa Rica: Boruca and Caribbean Bribri

Tourism in indigenous communities in Costa Rica: Maleku and Ngöbe

Tourism in indigenous communities in Costa Rica: Cabécar and Chorotega