Third in a four-part series on education and the pandemic in Costa Rica, inspired by a 2006 series by our co-founders that followed three second-graders through their school days in three very different Central Valley schools. Read Part One,”Following in Their Footsteps,” here, and Part Two, “Inequality and the Virus,” here.

Somehow, Steven Montenegro is instantly recognizable. Even though his glasses are gone, and a beard now frames his face; even though the quiet demeanor of his second-grade self has grown into an easy, jovial manner and a deep chuckle; even though he’s left Pacayas, Cartago and crossed the Central Valley to live among his girlfriend’s family in the Alajuela town of Palmares, his eyes are the same. And the fleeting impression I got in 2006 of a kid who was thoughtfully observing the world around him is quickly proved when Steven, now 23, expounds on the Costa Rican education system.

The system “focuses more on being a good employee, than on being a good business leader,” he says. “I never wanted to be an employee. I wanted to be the owner of a business, to be the one who hires the employees… For me, religion class was no good for anything. Some psychology would be better, something about how to organize a business.

“We’re taught to receive orders, not to be proactive,” he continues. “I think it’s a problem of our national mentality.”

The man who, in second grade, said his goal was to be an administrator at the dairy cooperative Dos Pinos—”Ah, I don’t remember that!” he says, and admits to having a terrible memory, not even remembering the name of his second-grade teacher until he’s reminded—now works as a technician at Telecable. He found that job after moving the 90 kilometers west to be with his girlfriend; before that, he’d been working at the butcher shop belonging to one of his 11 older siblings. He didn’t go to university because he couldn’t afford it, but he was looking at options before the pandemic struck. He’d like to study engineering or the mechanics of electric cars. Steven remembers elementary school very fondly: “lots of happiness, lots of color.”

In 2006, the principal of the Escuela Llano Grande, Ana Cristina Madrigal, told me that only 30% of Steven’s classmates would continue beyond sixth grade. (The current principal, Noily Villegas, says that that figure is now 100%, and attributes that to an increased interest among young people in preparing themselves for work outside of farming.) At the time, looking at the fresh-faced students in Steven’s second-grade class, it seemed like such a dismal statistic.

The reality, Steven tells me, was worse.

Of the students in the classroom with him on that day I visited in 2006, only Steven graduated from high school, and only two more even reached high school. He says they were girls who dropped out in the first year of high school, and became mothers, he thinks, not too long after that. The school in question is the Pacayas Vocational High School, or CTP Pacayas, just 4.5 kilometers from the Escuela Llano Grande. The school didn’t exist when his parents, Oscar and Vera, graduated from the Escuela Llano Grande and left their school careers behind. At the CTP, Steven specialized in agroindustry.

Steven defied the odds by reaching high school at all, and even more so by graduating. What’s more, while only 30% of the Escuela Llano Grande students were continuing on to high school in 2006, 100% of the 12 Montenegro Montenegro siblings accomplished that feat. Some of Steven’s siblings even went on to university, one at the public Distance Learning University (UNED), one at the private Fidelitas.

Asked how his parents managed this, Steven wastes no time in pinning the credit on his mother, a homemaker.

“It was really tough for my parents. It’s not such a developed country, and the economy isn’t very stable… Like any adolescent, you’d lose motivation, but my mom pushed me. She pushed all of us,” he remembers. “My mom was tough. You respected her, and she pretty much made us go to school. She was the one who se amarraba los pantalones.”

Amarrarse los pantalones: to tighten your belt, a phrase somewhat akin to the English “put on your big-girl panties.” Get strict, buckle down, call someone to task, bring everyone up to snuff… or sometimes, make budget cuts. In the case of Steven’s mother, doña Vera, it meant all of these things. The conversation left me reflecting on the ways in which a whole country of doña Veras, of parents and teachers and principals and Education Ministry leaders, had tightened their belts during the COVID-19 crisis. In Costa Rica’s education system, as in virtually all other systems around the world in 2020, the pandemic turned regular activities into impossibilities, and “someday it’d be lovely to…” scenarios into “we must do this tomorrow.”

Researcher Isabel Román, who heads the State of Education report series from the State of the Nation think tank, put it this way.

“We have an education system that’s really good at doing pilot plans,” she said with a smile over Zoom. “We’re super creative doing all kinds of pilot plans, but we have trouble with scaling. We have laboratory schools, but we never scaled them. Bilingual high schools? Great, right? Never scaled them… and the pandemic forced us to make changes for the next day. We’ll make mistakes, not everyone is prepared, but there’s no other way.”

So how did the people in charge of Costa Rican’s youth face a challenge like this? Today, rather than a deep dive, we offer you some skipping stones: quick takes on a few different ways that these people, like Steven Montenegro’s mother, buckled down and just got it through.

‘It smacked all of us across the face’

If you’re familiar with Costa Rica’s Ministry of Public Education (MEP), the country’s largest employer and one of Latin America’s most centralized education systems, a look down the list of its achievements during the pandemic creates a mental image of many thousands of people pulling up their pants at the same time. The MEP moving 50,000 teachers onto Microsoft Teams, in a matter of weeks? Creating a million email addresses in a system where only 36% of teachers, and a much lower percentage of students, used email before the pandemic? The launch of an online toolkit with basic teaching materials and forms, an online platform for college-bound high schoolers, a line for psychological help, online English training for kids, and more?

Let’s just say it bears out Isabel Román’s comment about the stress test and the drastic departure from the pilot mentality.

“This thing smacked all of us across the face at the start of last year,” says Melania Brenes, calmly. The Academic Vice-Minister of Public Education explains how the MEP, a highly centralized institution that is not known for quick pivots, threw itself into digital learning, training all of its 50,000 teachers in the use of Microsoft Teams (one teacher told us that the system crashed during the trainings), putting together the “autonomous guides” that families could use at home, and moving that figure of teachers using email from 36% to 90%. “The pandemic revolutionized many of the Ministry’s procedures and ways of doing things, whether in educational policy, budget, projects, planning… I feel that this had a very positive impact in turning processes that were taking a long time into shorter processes, or even innovating in how we did them.”

One example she gives is the digital enrollment that the Ministry began in 2020. For her colleague Paula Villalta, the Vice-Minister of Institutional Planning and Regional Coordination, 2020 was a red-letter year for the MEP not only because of the drastic, dramatic challenges facing its 1.2 million students and their families. It was a red-letter year because for the first time, the Ministry knows those students’ names. A long-term project to digitize MEP processes just happened to call for the Ministry to move its enrollment processes online in March, 2020, so that just as the pandemic began, the institution was beginning to collect students’ names and identification numbers for the first time in history. (Before last year, schools would simply inform the Ministry of the total number of students enrolled in each grade level; there was no central database showing any individual student’s path through the system.)

“This was crucial,” says Villalta. “Thanks to that information, we are able to achieve the unimaginable, which was providing continuity to educational services through virtual platforms.” While the lack of connectivity in many homes and schools meant that many students couldn’t access Teams at all, the fact is that without digital enrollment, the MEP wouldn’t even have been able to provide email addresses and Teams access to any of its students.

Both Villalta and Brenes recognize the many students left behind, particularly because of unequal access to technology. While Villalta states that the MEP ended the year with 96.5% of its students still in the system, she also admitted that “in the system” was hard to measure in 2020, and really just means that the students maintained some degree of contact with their teachers or schools. However, she says that 2020 gave the system a huge push in the right direction, and will allow the administrative divisions she oversees to analyze and detect problems much more quickly from here on out.

“The pandemic helped us,” she said. “It made all this happen much more quickly than we’d planned.”

‘One person’s problem is everyone’s problem’

For many schools and parents, email addresses, Teams access, or any kind of pedagogy were not even the top concerns during 2020. While specific stories of education going above and beyond filled social media using #vocaciondocente—for example, a teacher who bought and delivered gardening supplies for all her students so that they could do something productive and meaningful while classes where impossible, or a group of teachers in Bataan, Limón, who took their lessons to the airwaves, broadcasting because their students couldn’t connect—the most urgent efforts in a tourism-dependent country suddenly cut off from all tourism was putting food on the table.

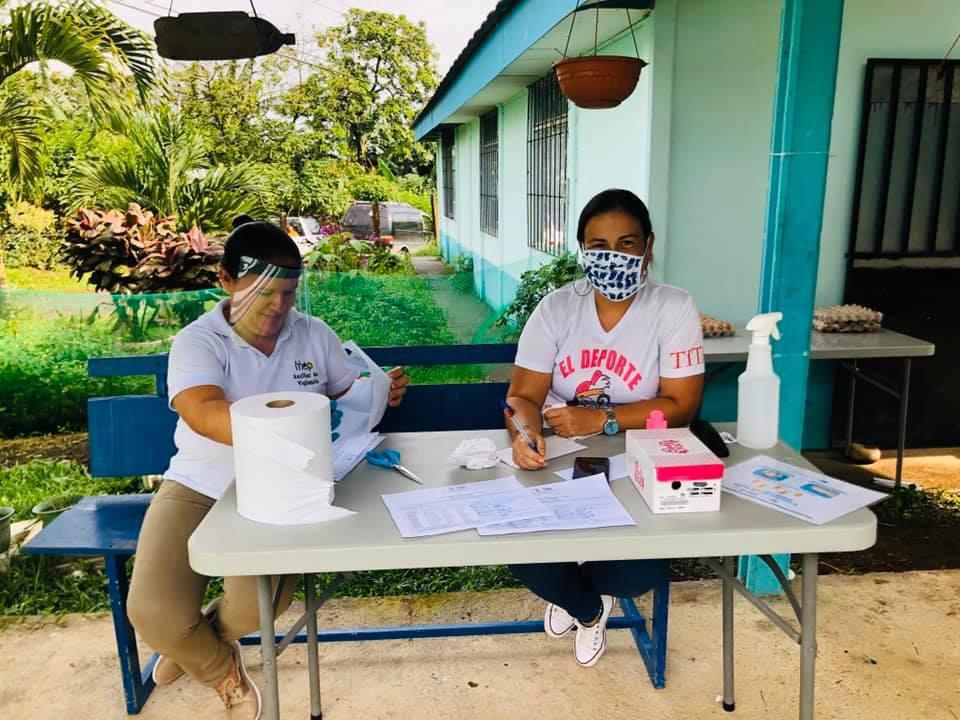

The necessary closure of the MEP’s thousands of school lunchrooms, an essential source of food for hundreds of thousands of students, required that the Ministry as a whole, and school principals in particular, get creative. The Ministry redirected its budget to purchasing food that were distributed to families when they came to school each month to turn in their completed guías autónomas, printed workbooks, and pick up new ones.

This food delivery was universal in primary school. MEP spokeswoman Nitzi Picado said that some people reacted poorly to this: “‘How is that possible, if the mom or dad still has a job?’ But it’s universal, for all beneficiaries.” In total, the MEP, through its Equity Programs Division, spent 103 billion colones (more than $168 million) on food packages for 855,000 children and their families in 2020. In 2021, the investment continues, but some schools are returning to in-person meals while others continue receiving packages.

The fact that the MEP’s enrollment cannot be updated in real time—or not yet, anyway—meant that some principals had to juggle those bags of food to cover everyone in the community. Principal Enizabeth Mejías Cruz, known in her community as doña Tita, encountered just such a problem at the Escuela El Jardín in Bijagua de Upala. Her official enrollment at the start of the pandemic stood at 97, but latecomers meant that her actual enrollment was 108. She had no food for 11 families in a tourism-dependent community whose local economy was devastated by the pandemic. She asked the MEP to send more, but again, since the real-time matrícula digital was only starting to become a reality, she was told there would be no way to update the numbers until July.

So: se amarró los pantalones.

“I talked to the parents,” she said, explaining that she negotiated with smaller families to give up one of their packets so that, among everyone, they could make sure the new families received something to eat. That’s how the Escuela El Jardín fed all 108 families until the numbers could be updated, months later. She attributes her ability to do this to the general community spirit of Costa Ricans, but especially that of her small town and school.

“Ticos are very friendly people, but this community of Bijagua is very united, very collaborative,” she said in a WhatsApp exchange. “One person’s well-being is everyone’s well-being, and one person’s problem is everyone’s problem… If only five tortillas arrive, well, I’ll cut those up into tiny pieces so that the whole population can have some.”

¿Así o más sencillo? What’s simpler than that?

‘The one thing people had was time’

The same spirit clearly pervaded in a very different school setting where the issues was not only how families would eat, but also how they would keep their kinds in school. Full tuition at the Monteverde Friends School averages about $4,000 per year, but its extensive financial aid packages mean that more than half the student body pays less than that, with many families paying just 10,000 per month, or about $16. (Because the school, unlike most public institutions, does not require uniforms or book purchases, this makes MFS a highly affordable alternative in the small cloud forest community.) Still, those 10,000 became impossible for many families when the pandemic closed off Monteverde to its main income source: tourism.

“When the pandemic hit and we closed last March, we went to an online methodology and we all took 50% pay cuts for the last three months of school,” director Sue Gabrielson explained. (MFS runs on an August-May schedule.) For the 2020-2021 year, “we reduced the budget by 25%, but most of our money comes from tuition, and we knew that our families wouldn’t be able to pay.

“The one thing that people had here was time,” she said. So the school worked with community partners who could put parents to work: first, parents planted trees with the Monteverde Institute, which was cut off from its usual streams of exchange students and volunteers, and had 10,000 trees on hand with no way to plant them. Next, parents worked on diverse climate-related projects with the Monteverde Commission for Resilience to Climate Change (CORCLIMA)—and then working together to raise funds to pay the parents for their work. This worked so well that MFS actually increased its enrollment during the pandemic, receiving students from another school in the community that had to close.

In the end, the school only “lost” one student who, despite extensive outreach by MFS to solve connectivity and equipment problems in the home, eventually went to the local school.

Today, Gabrielson says the school plans to continue this work-for-tuition programs, and is also using a similar scheme to address a related problem: some parents are working for tuition for their kids, but don’t have income so that their families can eat. So MFS is inviting unemployed or under-employed parents to complete work around the school campus in order to earn certificates that can be exchanged for food.

“It has nothing to do with me or us. It happened because the community already exists,” she says of these creative solutions. “There are constantly volunteers who are the foundation of the institutions here, so the program wasn’t very different from what people are used to… People here step up [in a crisis].”

‘Dual education: what does that even mean?’

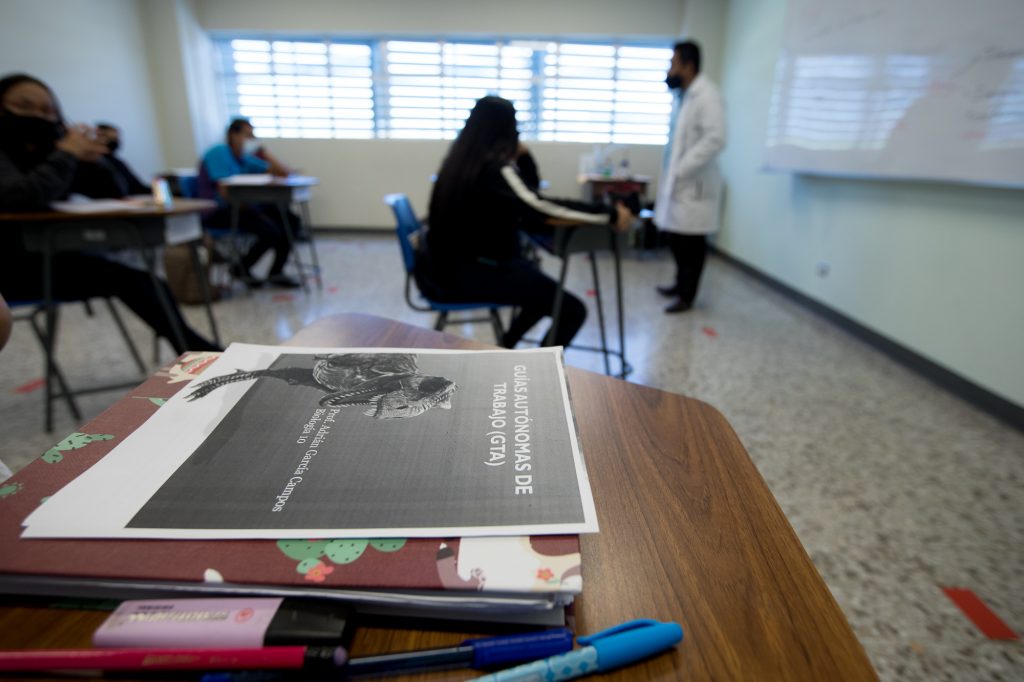

Of course, just when educators and families alike got used to a new normal for better or for worse–things changed again. The MEP announced a hybrid, or dual, return to in-person classes, with each school applying its own protocols and schedules depending on their student numbers, available space and ability to comply with health requirements. Student schedules, somewhat confusing in any year because of multiple shifts at many schools, became even more of a jigsaw puzzle, since students now go to school on different days and then have several at home where they’re meant to attend virtually, or do those printed autonomous guides at home.

Teresita Barquero, the principal of the Colegio Occidental de Cartago, saw the confusion coming. At her busy urban high school, she saw the enormous workload involved in using Teams with some students, using the printed with others, printing and distributing the work and planning month to month. She knew that, especially in the face of the uncertainty facing the education system for the beginning of a new school year, she wanted to try somethign different.

Barquero wrote to Vice-Minister Melania Brenes in late 2020 and asked if she could create digital antologías, or anthologies, that would sum up six months’ work, readings and activities at one time so that teachers and families would not have to deal with creating, printing and distributing a new set of autonomous learning guides. Brenes responded that there was no way of knowing whether or not distance learning would continue in 2021. Eventually, Barquero decided to do it anyway.

“It was a massive workload for my colleagues, tons and tons of work,” she recalls. Each student received a six-month learning guide with the autonomous guides, learning materials and other materials. Barquero also conducted a detailed survey of students’ connectivity and access to devices to help her teachers figure out which students would require a print version: anyone who had connectivity in the home, even if this was limited to a poor connection and a cell phone, received the digital version. “We have some colleagues that aren’t very technologically skilled, but there was always someone who helped… We sent the students a message, don’t buy school supplies, don’t buy notebooks, because you won’t need it.”

Now, with hybrid or dual learning taking place, teachers use their in-person time to explain the upcoming weeks’ activities and answer questions. They don’t have to worry about providing materials or, in essence, week-to-week lesson planning, since they created an entire semester before it began.

“Dual education: what does that even mean?” Barquero laughs, explaining that in the total absence of clarity, her team came together to figure out a way. “I’m so proud of my school, of my chiquillos and of my colleagues.”

These educators. These parents. Doña Vera, who got her 12 kids through school through the sheer power of her personality. The parents at Escuela El Jardín who gave up part of their food allotment so other families could receive something. The parents in Monteverde who worked to keep their kids in a unique private school environment. Doña Teresita, a gung-ho principal and herself the mother of a teenager and a two-year-old, who rallied her teachers into long weekends of intense work to prepare the school for whatever would come in 2021. Private-school parents, or public-school parents with home connectivity, shepherding their kids through online classes; parents picking up food packets and printed guides each month; parents WhatsApping with their kids’ teachers or simply experiencing radio silence.

It’s moving, what they accomplished.

At the same time, it’s hard to shake the impression of people working hard and long to connect hoses that can spray water on a massive house fire, while a fire truck holding 750 gallons is standing untapped at the curb. That is, it’s hard not to feel that while the pandemic itself was out of everyone’s control, many of the problems these families and schools were facing should not have existed at all in 2020.

To switch metaphors, those pants should already have been belted very securely by national entities with enormous resources at the country’s disposal.

Why is that? Next time, in part four: Costa Rica’s connectivity challenge.

Mónica Quesada Cordero contributed reporting to this piece.

Read more about organizations mentioned in Monteverde and how to support them on the pages for the Monteverde Institute and the Monteverde Community Fund on the Amigos of Costa Rica site.