First in a four-part series on education and the pandemic in Costa Rica. We invite you to read “Inequality and the virus”, “The equalizers”, and “Searching for a renaissance.”

That grin: a mischievous flash under hair shaped into crocodile spikes.

Curls that were perfectly arranged, yet bounced and flew when their wearer raced down the stairs of an iconic school building, her feet pounding towards the release of the recess yard below.

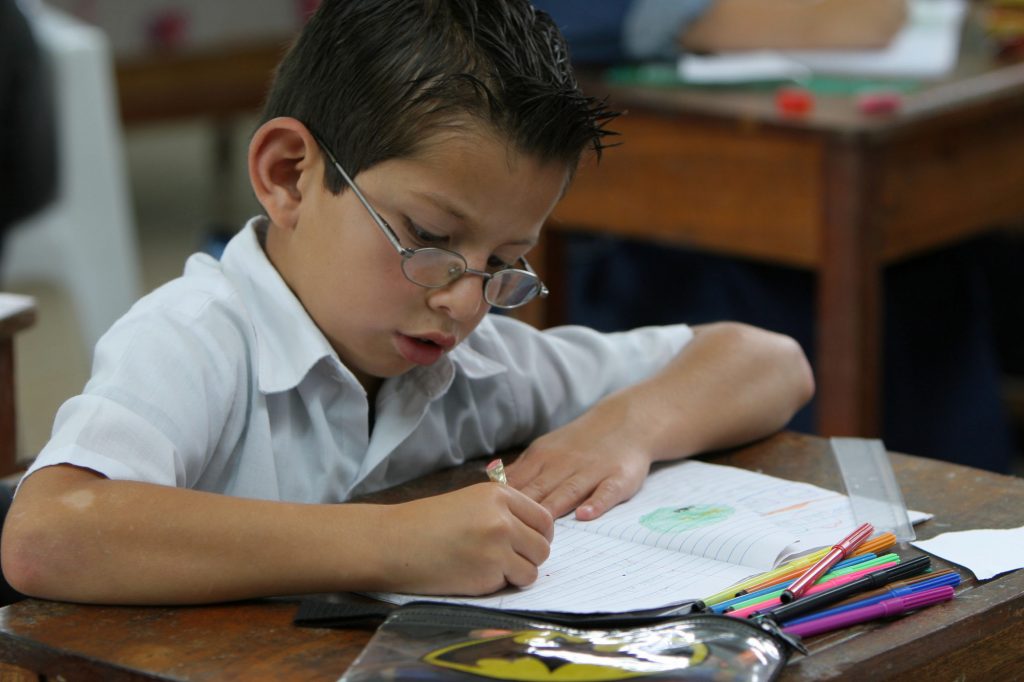

A sculptural masterpiece over glasses that framed a steady, serious gaze.

I remember the hair so clearly, for some reason. Greivin. Ariana. Steven. Three second-graders who, in 2006, let a journalist follow them around to find out what lessons a single day in each of three very different public schools might teach about the Costa Rican education system. Three second-graders who, despite attending school in the same country—the same valley, in fact—ate their snacks and learned their lessons and traveled to and from school in very different ways.

As a reporter at The Tico Times, then an English-language print newspaper, I wanted to find out how and why those differences occurred. I was new to Costa Rica, and equally new to journalism, and nearly as bright-eyed and energetic as my three elementary-school subjects.

Today, 15 years later, everything is messier. My own life as the mother of my own second-grader; the lives, surely, of those three children, now navigating their way through their early 20s in the middle of a global pandemic; and, certainly, my understanding of the untidy realities of Costa Rican education.

Costa Rica is rightly renowned for its commitment to education. As many a political speech and tourism brochure will remind you, the country has chosen to invest in its people instead of in its military, famously abolished in 1948. The results are visible in sky-high literacy rates and an enviable educational infrastructure, most easily visible in the presence of a village school even in tiny Costa Rican communities.

However, as with most any education system in the world, there are no neat edges. The Ministry of Public Education, the country’s largest employer, runs one of the most centralized education systems in the hemisphere, with bureaucratic tangles that are legendary. Those picturesque one-room schools have spread education spending very thin, increasing access but dispersing resources. A change-averse system has struggled to adapt to technology, to say the least. Over the years, I watched as the issues and indicators explored in that 2006 series passed in and out of the headlines: curricular reforms, educational spending increases, efforts to reform teacher hiring policies despite fierce opposition from unions.

Then came 2019, when teacher strikes suspended school for approximately 80 days.

Then came 2020. Schools were closed in March, just over a month into the curso lectivo.

As El Colectivo 506 began publication in January 2021 and the nation’s schools began to gear up for what everyone agreed would be a messy and confusing return to in-person learning, it seemed obvious that our new media organization would need to explore two questions: What happened to Greivin, Ariana, and Steven, and the schools they attended, over the past 15 years and the past 12 months? And how are second-graders in Costa Rica, along with the rest of the country’s students, faring today?

One day in second grade

“Greivin Cruz, 8, attends Escuela Finca La Caja in La Carpio, an impoverished neighborhood in western San José; he walks to school each day along bumpy dirt paths through a community where Costa Ricans and Nicaraguan immigrants live in often-improvised dwellings, until he reaches a school crammed with more than 2,000 students,” read the article published by The Tico Times on June 30, 2006. “A comfortable minibus takes Ariana Solano, 7, from her home in northern San José to the Escuela Buenaventura Corrales, better known as the Escuela Metálica, a downtown landmark next to the lush Parque España. Renowned for its architecture and for the quality of its instruction, its alumni include ex-Presidents, Cabinet ministers and other illustrious Ticos.

“Steven Montenegro, 8, walks past cow pastures and potato fields—if he’s lucky, he might catch a ride on an oxcart—to Escuela Llano Grande de Pacayas in a town of the same name. One of 12 children, he wants to grow up to be an administrator at the dairy cooperative Dos Pinos.”

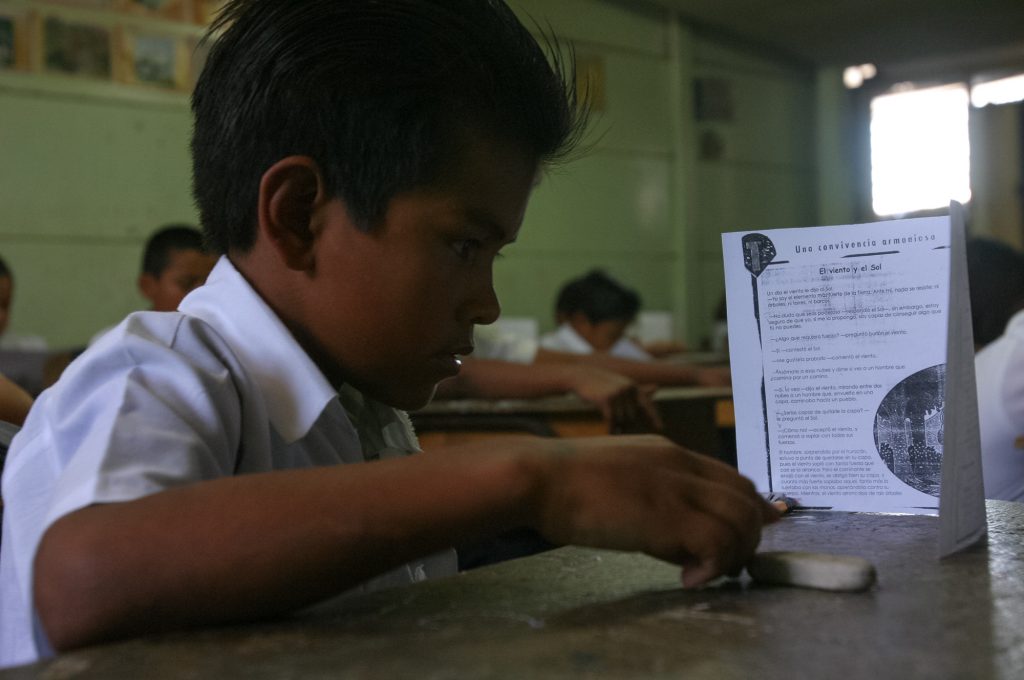

Greivin, in La Carpio, was very reserved. He tolerated the presence of the reporter beside him, glancing sideways at me every so often. He had a new watch on the day I spent with him, and was showing it off to his classmates. He also locked and relocked a padlock on his backpack every time he took everything out; he’d had things stolen at the school before, his mother Hortensia Ramírez said later. His teacher, Dennis Alvarez, struggled to lead a read-aloud session during which no one in the hot, dim room could hear anyone else speak because of the deafening din coming through the thin walls. Ironically, the story the group was struggling to read was about a power struggle between sun and wind that involved the sun shining ever hotter on a suffering human. As the classroom grew ever more stifling, students gave up reading the photocopied story and fanned themselves with it instead.

School sociologist Italo Fera told me at the time that conditions in the building, which would later draw attention from the Public Health Ministry because its insufficient water supply, amounted to “educational terrorism… The people with the most instructional needs are the least prepared people. Unfortunately, we’re reproducing the cycle of poverty.”

With 2,000 students and only 15 classrooms in the main building, the Escuela Finca La Caja broke its school day into three shifts. Grevin’s shift on that day in March 2006 ran from 10:45 a.m. to 2:20 p.m. However, during that time, a minute-by-minute record of his activities showed that he received only two hours and 45 minutes of instruction. “To make up for the short shifts, the students attend school Saturdays, although Alvarez tells the class that this week’s Saturday session will be used to clean the classroom,” the story says.

That gap in instructional time was the most evident difference between the three schools that could be observed in a single day, which is, of course, far too short for any more sophisticated conclusion. Steven, far across the Central Valley in the highlands of Cartago, received even less on the day I spent at the Escuela Llano Grande de Pacayas 15 years ago this month: two hours 30 minutes, to be precise. This was just 15 minutes less than Greivin, but two hours less than Ariana, who received her classes in a gorgeous and historic classroom overlooking the chain of parks that make east-central San José the pleasantest corner of the city. Even considering the Saturday classes offered in Pacayas, like La Carpio, this breach meant that Steven and Greivin might receive the equivalent of 89 days less per year than Ariana of school. (If you’re keeping score, that’s more than the considerable amount students lost in 2019 because of the national strike.)

Looking back, the first question is simply how many of the three managed to graduate from high school. The odds were in Ariana’s favor in 2006, but against Greivin’s and Steven’s. Greivin’s mother, Hortensia, expressed doubt back then that her kids would attend high school; there was none in La Carpio, and the monthly cost for transportation would cost at least $9-12 per month. Steven’s school principal, Ana Cristina Madrigal, said that only 30% of the school’s students would continue past sixth grade. His parents, Vera Montenegro and potato farmer Oscar Montenegro, said at their home up a steep hill from the school that they’d both attend the school themselves and dropped out after sixth grade because of the cost of traveling to and from high school.

In the plus column for Steven, however, was the fact that his older siblings were studying at university or at the vocational high school in the town of Pacayas at the time of that interview. Despite the $400 per month that his parents they estimated for uniforms, supplies, transportation and other costs related to the education of their 12 children, they were making it work so that their kids could go further in school than they had.

“What’s next for this little boy, whose parents describe him as smart and industrious?” I wrote back then. His mother wished there were more for him, like English or computers: “There’s something missing, I imagine,” she said.

Along with my Colectivo 506 co-founder Mónica Quesada, who had reported the series with me back in 2006, I wanted to find Greivin, Ariana and Steven, but wasn’t sure we’d be able to. We thought we’d start, instead, with something we knew would still be there: the schools where they’d played and learned.

Fifty kilometers, three realities, one protocol

A comparison done over a period of weeks in 2006, one foot and by bus, can also be done in a single day by car—especially when health protocols prohibit journalists’ entry to classes, shortening the visit and limiting our view to what can be seen from outside classroom walls.

This abbreviation proved enlightening. It is astonishing to greet the day wrapped in a scarf in the hills of Pacayas de Cartago, where quiet kids from preschool to sixth grade stand quietly in their pristine, pressed uniforms on the yellow dots painted on the sidewalk to ensure social distancing; sweat at midmorning 38 kilometers away outside the Escuela Metálica’s pink facade, imported from Belgium, near passersby resting on quiet benches among a sea of green and homeless men sleeping in the blazing sun; and, by noon, after another 11 kilometers of crowded San José roads, enter the halls of the three-year-old school that is now the pride and joy of La Carpio.

While this cross-valley pilgrimage can’t come anywhere near chronicling the diverse realities outside the Central Valley, it does, at least, provide an efficient and remarkable cross-section of life in this particular ring of mountains. It also shows how the pandemic has unified the country’s schools in at least one way. The protocols that were required for reopening this year look very similar, despite the head-spinning contrasts in almost every aspect.

The students, masked, line up outside the schools as they have since Feb. 8, when the 2021 school year began. They wear masks, as they will throughout the school day. They wait for the school conserje—janitor, althought the more literal translation of “concierge” seems more appropriate for their hands-on role at the school gates during the pandemic—or other staff to take their temperature, supervise their careful hand-washing, and send them to their classes. At all three schools, health protocols for the return to classes are posted everywhere, in great detail.

The Buenaventura Corrales is unchanged, and, because it is entirely enclosed by that impressive metal facing, it’s impossible to guess at any alternations within—although the fact that the school secretary and much of the staff, including Ariana’s second-grade teacher, Guiselle Quirós, continue in their posts, provide a deep sense of continuity. Steven’s school, however, is notably improved. While its student body remains virtually the same size (57 this year, up from 52 in 2006), it features new fencing, a lovely playground and new classrooms, too.

Parents, mostly mothers and grandmothers, wait outside the school with their children; many of them perform the sign of the cross on the kids as they say goodbye. Janitor Rodolfo Solano, who has worked at the school for 23 years, says he remembers our visit, instantly identifies the oxcart driver who would have taken Steven home that day (don Miguel Masis), and even points out a man driving by the school: “That’s Steven’s brother,” he says with a smile and a wave, quickly returned.

The uniforms are white and navy, with maroon ties for the girls and boys in the second cycle, fourth through sixth grade. Here as around the world, the mask style game is strong. Hello Kitty. Minnie Mouse. Don Rodolfo wears a Saprissa mask, morado on white. He and the school’s seven teachers continue to oversee the monthly handing out of basic food supplies to families in exchange for their kids’ completed assignments. While kids can come to school in person a few days here and there, remote education continues on the other days—which, in rural areas like this with limited connectivity, often means that parents oversee their kids’ completion of printed packets, rather than connecting to online classes as they do where connectivity is better.

If the Escuela Llano Grande has been spruced up and expanded, the Escuela Finca La Caja is totally transformed—right down to the name. The Escuela La Carpio was inaugurated with great fanfare in 2018, three years ago this month, by then-President Luis Guillermo Solís and a host of other officails following a 23-year effort to improve the school. Exhaustive community lobbying eventually resulted in a $6.4 million investment from the Inter-American Development Bank.

The four-story building is a towering presence in the shantytown, where plenty of unmasked residents walk the busy streets. Official statistics put the population of this settlement, created in 1993, at 25,000, although the weekly Semanario Universidad reports that neighbors’ informal estimates put it closer to 30,000. This community has arguably been one of the hardest hit in the entire country by COVID-19: its overcrowded living conditions led to outbreaks in May 2020, and the disappearance of both formal job and informal occupations, such as street sales, hit the community hard.

At least the kids are back to school. Despite the fact that the student body here is nearly 33 times that of the Escuela Llano Grande (1,870, with approximately 125 staff members), the entry process is nearly as orderly. Staff members consult clipboards listing the dizzying array of classes and make sure the students are here at the right time, and that their teacher is ready to receive them. When one staff member notices that the floor mat where students wipe their shoes has run out of the powerful disinfectant that’s supposed to fill it, someone is along with a bottle in just seconds.

“Do you know where you’re going?” a janitor asks a little girl in a pink mask, black-rimmed glasses and a tight bun. She nods and off she goes to the hand-washing station set up in the long courtyard at the heart of the school.

School psychologist Rosibeth Alvarado Sandoval, who says she’s been working throughout the pandemic with students dealing with anxiety, fear and phobias, says it’s essential for the kids to have contact with their teachers again, even in this limited way. But she’s clear that there’s a long road ahead.

“The biggest impact of the pandemic is going to come after its over, on a mental level,” she says.

The search continues

Maybe I remember those kids by their hair so because, when I became a mother myself in Costa Rica, hair would become an area where I never quite measured up. Kids always seem to look so neat in this country, as did Greivin, Ariana and Steven: girls’ hair subdivided into tidy braids, boys’ combed and Plastigelled into submission. One preschool teacher redid any hairstyle I sent my daughter in with and sent her home with a better version. If I’d pulled it into a side ponytail to keep her fine strands out of her eyes, she’d come home with a side French braid, a wordless commentary on my sub-par skills.

I didn’t understand, back in 2006, just how much goes on under a second-grader’s head of hair, how much that brain is observing and processing. I didn’t know what a second grader really is, how much of our personalities and lives have been set in motion by that time. I didn’t know, either, that if I’d spent more time, much more, with Greivin, Ariana and Steven and their families, I could have built the trust that’s needed for any of us, but especially a kid that age, to offer up the insights only he or she can provide. I could have learned so much more from Greivin and Arianna and Steven, if I’d known what to ask.

I wanted another chance. A chance to ask them about their lives since 2006, their schooling, how far they managed to get, what they do now. What they think about when they look back on those early days. What they think of the system that formed them. How they’re doing during a pandemic that continues to ask far too much of almost all of us.

I was just drawing breath to expound on how difficult it might be to track down the kids, now 22 and 23, when Mónica said: “Just look on Facebook!” Of course. We typed in names, compared notes over our Zoom call, scrutinized the photos to see if these could be the same kids we remembered. Friend request? Sent. My texts on Messenger were long and awkwared, with a link to that old story. “Was that you?”

“Wao,” comes the first answer, just moments later. “I’m reading this and I can’t believe it. But yes, yes, that was me!”

Next week: Starting with a conversation with our first of the 2006 second graders, we explore how the virus has cast new light on inequalities—especially when it comes to technology.